Part five of a six-part series on Julian Assange and the Espionage Act.

Read: Part One, Two, Three and Four.

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

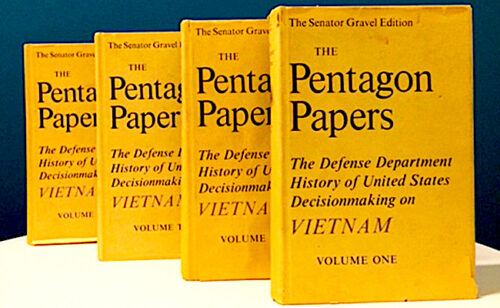

The 1971 decision of the Supreme Court against the Nixon administration’s “prior restraint” injunction of The New York Times, allowing the press to continue publishing the Pentagon Papers, is well known.

Less known is that the Nixon Justice Department empaneled a grand jury in Boston with the intention of indicting reporters from the Times, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe under the Espionage Act for publishing articles based on the classified Papers.

It was the second attempt, after FDR, by an administration to charge reporters with espionage for possessing and publishing state secrets.

Nixon was able to set up the grand jury because the Supreme Court made clear in the Times case that though the government could not stop a newspaper from publishing classified matter in advance, it could pursue prosecutions after publication for violating the Espionage Act.

This is highly relevant to the Assange case as his prosecutor, James Lewis QC, brought it up during the September extradition hearing in London. At first Lewis stressed to the court the U.S. view that Assange was not a journalist. After a succession of defense experts dismantled that view, Lewis essentially conceded that Assange was a journalist, but that the Espionage Act gave the government the authority to prosecute journalists after publishing defense information.

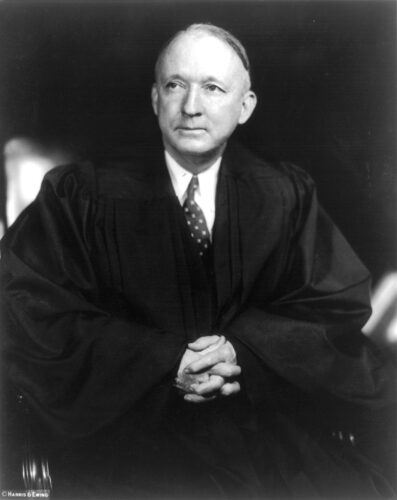

“Justice Hugo Black: ‘The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government.'”

Justice Byron White in the Papers case said newspapers were “not immune from criminal action” for publishing classified information. “Failure by the Gov. to justify prior restraints does not measure its constitutional entitlement to a conviction for criminal publication. That the Gov. mistakenly chose to proceed by injunction does not mean that it could not successfully proceed in another way.”

The question of prior restraint versus no restraint after publication was debated at the founding of the United States. James Madison believed it a “mockery to say that no law should be passed preventing publications from being made, but that laws might be passed for punishing them in case they should be made.” Had Madison’s view prevailed, the Espionage Act could not have been used against a journalist like Assange post publication.

But instead the Espionage Act adopted the logic of Adam’s pernicious 1798 Sedition Act, which was based on a 1769 commentary by William Blackstone, an English jurist, judge and Tory politician, who wrote, “liberty of the press … consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published.”

In the Papers’ case, the Boston grand jury was disbanded only after prosecutorial misconduct in the trial of the Times’ source, Daniel Ellsberg, led to his case being dismissed. Ellsberg was the first newspaper source to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act. When the Times’ reporters under grand jury scrutiny, Neil Sheehan and Hedrick Smith, learned that Ellsberg’s phone had been tapped, they asked the government whether they had been tapped as well in their conversations with their source. Shortly after that, their case was dropped, Ellsberg told me in an interview.

The Nixon Justice Department was in a position to bring Espionage Act charges against then U.S. Sen. Mike Gravel of Alaska. After being turned down by several senators, including Sen. George McGovern who was planning a run for president, Ellsberg found Gravel willing to read the Papers out loud into the congressional record during a Senate subcommittee meeting.

On June 29, 1971, the night before the Supreme Court decision, Gravel legally revealed the classified Pentagon Papers on Capitol Hill because of the U.S. Constitution’s Speech or Debate clause, which says that, “for any Speech or Debate in either House,” members of Congress “shall not be questioned in any other Place.” That means any senator or representative can in effect declassify any material without penalty if done during a legislative act.

But when Gravel arranged with Beacon Press in Boston to publish the Papers as a five-volume book, he lost this legal protection. Gravel told me for the book we co-authored, A Political Odyssey, that he did this because after the Supreme Court judgement the newspapers nonetheless stopped writing stories based on the Papers. Gravel feared Nixon would indict him. While the government could not stop Beacon from publishing, it could prosecute afterward. Nixon left Gravel alone, however, and instead went after the publisher, the way Trump went after Assange.

Gobin Stair, executive director of Beacon Press, told a conference in Boston in October 2002 that he decided to publish the Papers after Nixon picked up the phone to threaten him: “I recognized his voice, and he said, ‘Gobin, we have been investigating you around Boston. I hear you are going to do that set of papers by that guy Gravel.’ It was obvious he was going to ask me not to publish it. The result was that as the guy in charge at Beacon, I was in real trouble. To be told by Nixon not to [publish this book], convinced me that it was a book to do.”

On Sept. 17, 1971, two Pentagon goons replete with fedoras, trench coats, and cigarettes showed up at Beacon’s offices on the hill overlooking Boston Common. They tried to intimidate Stair. They demanded the Papers for military analysts to study. They checked the photocopy machine to see if Ellsberg had used it. But the tough-guy act failed. Stair stalled by agreeing to a follow-up meeting. Then the Pentagon suddenly dropped the matter.

Twelve days before Beacon Press’ publication date the Pentagon published its own paperback edition of the Pentagon Papers. So much for harming national security. It was Nixonian vindictiveness to take the wind out of Beacon’s sails and sales. What he considered stolen property he put on sale at $50 for a 12-volume set.

Secrecy and the Press’ Role

Supreme Court justices in the Pentagon Papers case underscored the role the press plays to reign in authoritarian leaders who over-classify information to protect their interests in the name of “national security.” In retrospect, the justices’ opinions amount to a defense from the highest levels of U.S. government of the work of Assange and WikiLeaks.

Justice Hugo Black challenged the “national security” mantra as a subterfuge to justify secrecy and repression. In his Pentagon Papers opinion, he wrote: “The word ‘security’ is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment. The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security for our Republic.”

He went on:

“In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government.

The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the Government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.

In my view, far from deserving condemnation for their courageous reporting, The New York Times, The Washington Post and other newspapers should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly. In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam war, the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the founders hoped and trusted they would do.” [Emphasis added.]

Justice Potter Stewart wrote in his Pentagon Papers opinion that:

“In the absence of the governmental checks and balances present in other areas of our national life, the only effective restraint upon executive policy and power in the areas of national defense and international affairs may lie in an enlightened citizenry— in an informed and critical public opinion which alone can here protect the values of democratic government. For this reason, it is perhaps here that a press that is alert, aware, and free most vitally serves the basic purpose of the First Amendment. For without an informed and free press there cannot be an enlightened people.”

Justice William Douglas went even further, questioning whether the Espionage Act related to the press at all, and whether journalists and publishers can be prosecuted after publication, as Assange has been. Douglas wrote:

Justice William Douglas went even further, questioning whether the Espionage Act related to the press at all, and whether journalists and publishers can be prosecuted after publication, as Assange has been. Douglas wrote:

“There is … no statute barring the publication by the press of the material which The Times and Post seek to use. 18 U.S.C. Section 793 (e) provides that ‘whoever having unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any document, writing, … or information relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, wilfully communicates … the same to any person not entitled to receive it … shall be fined not more than $10, 000 or imprisoned not more than 10 years or both.”

The Government suggests that the word, ‘communicates’ is broad enough to encompass publication.

There are eight sections in the chapter on espionage and censorship, Sections 792-799. In three of those eight, ‘publish’ is specifically mentioned: Section 794 (b) provides, ‘Whoever in time of war, with the intent that the same shall be communicated to the enemy, collects records, publishes, or communicates … [the disposition of armed forces].’

Section 797 prohibits ‘reproduces, publishes, sells, or gives away’ photos of defense installations.

Prior Restraint in Britain

The Pentagon Papers case revealed one difference between U.S. and British law in regard to prior restraint. While the Supreme Court would not allow publication of the Papers to be enjoined, the absence of a First Amendment in Britain has freed the government to halt publication on occasion. A most celebrated case was that of the book Spycatcher, a memoir by Peter Wright, a former assistant director of MI5. The British government got an injunction in 1985 to ban its release.

The Margaret Thatcher government then went to court in Australia to ban the book there, but lost the case, defended by future Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. The book was released in Australia and in the U.S. on July 31, 1987. English newspapers tried to publish excerpts but were served gag orders and later were charged with contempt of court. The ban on English papers was then partially lifted by three High Court judges a week before U.S. and Australian publication, but three weeks later senior Law Lords reinstated the ban on appeal. Lord Ackner for the 3-2 majority said if the ban were not reimposed, the Attorney General would be “prematurely and permanently” denied court protection. He said:

“It would be established, without trial and for all time, that by the simple expedient of going abroad, and arranging publication in the press in a country such as the United States — where there is no remedy by way of injunction — the courts in this country would become incapable of exercising their well-established jurisdiction. Your Lordships would have established a charter for traitors to publish on the most massive scale in England whatever they had managed to publish abroad. …

If the publication of this book in America is to have, for all practical purposes, the effect of nullifying the jurisdiction of the English courts to enforce compliance with the duty of confidence, . . . then, . . . the English law would have surrendered to the American Constitution. There the courts, by virtue of the First Amendment, are, I understand, powerless to control the press. Fortunately, the press in this country is, as yet, not above the law.”

Labour MP Tony Benn defied the ban by reading aloud from the book in Hyde Park’s Speakers Corner. British newspapers reacted with disdain. The Daily Mail pictured the three Law Lords upside down on its front cover with the headline: “YOU FOOLS.” The Economist ran a blank page with the explanation that in only one country were excerpts banned. “For our 420,000 readers there, this page is blank — and the law is an ass.”

In October 1988 the Law Lords reversed themselves, allowing publication because, as the BBC reported, “any damage to national security has already been done by its publication abroad.”

The British government’s actions were not based on statutory authorization for prior restraint but rather on common law. Because there is no formal censorship clause in the Official Secrets Act of a kind that President Wilson had sought, instances of British prior restraint cannot be laid on the Act, but rather on no First Amendment-type legislation and Britain’s lack of adherence to Article 10 of the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees free speech.

Tomorrow: Assange in the Dock

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @unjoe