Part four of a six-part series on Julian Assange and the Espionage Act.

General Douglas MacArthur signs as supreme allied commander during formal surrender ceremonies on the USS MISSOURI in Tokyo Bay, Sept. 2, 1945 (US Navy)

Read: Part One, Two and Three.

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

With few exceptions, American newspapers voluntarily censored themselves in the Second World War before the government dictated it. In the Korean War, General Douglas MacArthur said he didn’t “desire to reestablish wartime censorship” and instead asked the press for self-censorship. He largely got it until the papers began reporting American battlefield losses.

On July 25, 1950, “the army ordered that reporters were not allowed to publish ‘unwarranted’ criticism of command decisions, and that the army would be ‘the sole judge and jury’ on what ‘unwarranted’ criticism entailed,” according to a Yale University study on military censorship.

After excellent on-the-ground reporting from Vietnam brought the war home to America and spurred popular anti-war protests, the military reacted by blaming the news media for its defeat. It then instituted, initially in the First Gulf War, serious control of the press by “embedding” reporters from private media companies, which accepted the arrangement, much as World War II newspapers censored themselves.

FDR Targets Newspaper

When The Chicago Tribune defied World War II censorship in 1942 by reporting that the U.S. Navy knew Japan’s strategy for the Battle of Midway — evidently by decoding Japanese communications — President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to use the Espionage Act to prosecute a reporter for the first time for publishing defense information. His Justice Department had a grand jury empaneled in Chicago, which, unlike in the Assange case, refused to return an indictment.

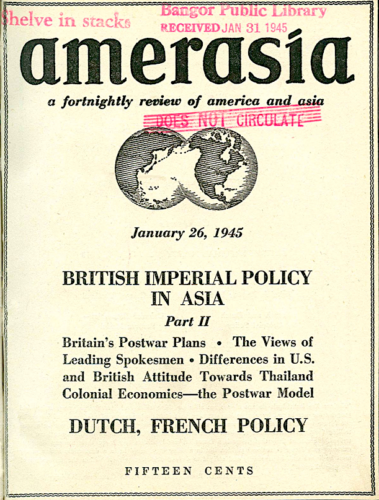

Three years later the FBI raided the offices of Amerasia, a pro-communist publication, which had obtained classified information, including up to “Top Secret,” and published articles based on it. It seemed a clear, technical violation of the Espionage Act for possessing and communicating state secrets, but a grand jury again refused to indict under the Act because the publication did not pass secrets to a foreign power, as Assange has not.

Right-wingers in Congress were incensed and, helping to launch the McCarthyist era, mobilized to pass in 1950 amendments to the Espionage Act, including section 798 and sub-sections 793(e) and (g), which has directly affected Assange.

While the U.S. prosecution in his extradition case at first argued that he was not a journalist and its case was not about journalism, it later changed tack — after defense witnesses strongly indicated that it was — and argued instead that Assange had violated sub-section 793(e) for possession and publication of defense information.

In a sense it can be said that Assange is at least an indirect victim of McCarthyism.

McCarran Internal Security Act

The McCarthyist scare was just underway in 1950 when an amendment to the Espionage Act added Section 793 (e) and (g) and Section 798. The Act that contained the amendments was named after its sponsor, Democratic Sen. Pat McCarran of Nevada.

While the act was being debated in 1949, West Virginia Sen. Harley Kilgore wrote to McCarran, warning that the amendment “might make practically every newspaper in the United States and all the publishers, editors, and reporters into criminals without their doing any wrongful act.”

The U.S. attorney general wrote at the time, falsely it turned out, “that nobody other than a spy, saboteur, or other person who would weaken the internal security of the Nation need have any fear of prosecution under either existing law or the provisions of this bill.”

The language in the British and U.S. espionage laws that have been considered is exceedingly broad, giving governments on both sides of the Atlantic wide berth to bring prosecutions on anyone. The 1950 amendments to the Espionage Act made that language broader still.

The most significant 1950 change to the Espionage Act was to remove intent and make mere retention of defense information illegal. According to Harold Edgar and Ben Schmidt Jr. in the May 1973 edition of Columbia Law Review:

“The basic provisions of sections 793 and 794 have been changed importantly only once since 1917. As a little-noted aspect of the massive Internal Security Act of 1950, section 793 was extended by the addition of subsection (e). This provision departed from the established pattern of the 1917 Act by imposing a prohibition applicable to everyone, not conditioned on any special intent requirement, on communication of information relating to the national defense to persons not entitled to receive it. Mere retention of defense information was also made a crime.”

Subsection (e) removed the requirement that anyone who had unauthorized possession of state secrets return it to proper authorities on their “demand.” It now has to be returned without any such demands. So a journalist like Assange who received defense information without authority, did not immediately return it, and communicated it could more easily be prosecuted with the government not having to prove any intent on his part.

Edgar and Schmidt add:

“The sweep of these provisions seems incredible when measured against the congressional antipathy, manifested both in the 1917 debates and in subsequent confrontations with the problem of secrecy, to broad prohibitions that would hinder public speech on defense matters. No special culpability requirement explicitly restricts their reach. Barring the possible effect of limiting constructions, any ‘communicating’ of defense material or information to anyone not authorized to hear about it is a serious criminal offense. Even retaining possession of such material is unlawful for those who lack special authorization.

If these statutes mean what they seem to say and are constitutional, public speech in this country since World War II has been rife with criminality. The source who leaks defense information to the press commits an offense; the reporter who holds onto defense material commits an offense; and the retired official who uses defense material in his memoirs commits an offense.”

The McCarran Act’s adoption of 793 (g) added conspiracy to the Espionage Act. It says: “If two or more persons conspire to violate any of the foregoing provisions of this section, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each of the parties to such conspiracy shall be subject to the punishment provided for the offense which is the object of such conspiracy.” Assange was also charged under this section for allegedly conspiring with his source, Chelsea Manning, in what is otherwise seen as a routine relationship between a reporter and a source.

The Internal Security Act also went as far as creating a Subversive Activities Control Board to investigate someone merely suspected of engaging in subversive activities. It created an emergency detention statute giving the president authority to arrest “each person as to whom there is a reasonable ground to believe that such person probably will engage in, or probably will conspire with others to engage in, acts of espionage or sabotage.” (The Board was defunded in 1974.)

President Harry Truman vetoed the McCarran Act. Without addressing the changes to the Espionage Act, Truman said McCarran threatened “the greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798;” made a “mockery of the Bill of Rights” and was a “long step toward totalitarianism.”

But a McCarthyist Congress overrode Truman’s veto. Had it not, it may have been harder to indict Assange.

The Act’s Territorial Reach — The Amendment That Imperils Assange

If the original 1917 Espionage Act were still in force, the U.S. government could not have charged Assange under it because the 1917 language restricted the territory where it could be applied:

“The provisions of this title shall extend to all Territories, possessions, and places subject to the jurisdiction of the United States whether or not contiguous thereto, and offenses under this title when committed upon the high seas or elsewhere within the admiralty and maritime jurisdiction of the United States …”

WikiLeaks publishing operations have never occurred in any of these places. But in 1961 Virginia Congressman Richard Poff, after several tries, was able to get the Senate t0 repeal Section 791 that restricted the Act to “within the jurisdiction of the United States, on the high seas, and within the United States.”

Poff was motivated by the case of Irvin Chambers Scarbeck, a State Department official who was convicted of passing classified information to the Polish government during the first Cold War.

Polish security agents had burst into a bedroom to photograph Scarbeck in bed with a woman who was not his wife. Showing him the photos, the Polish agents blackmailed Scarbeck: turn over classified documents from the U.S. embassy or the photos would be published and his life ruined. Adultery was seen differently in that era.

Scarbeck then removed the documents from the embassy, which is U.S. territory covered by the Espionage Act, and turned them over to the agents on Polish territory, which at the time was not.

Scarbeck was found out and fired, but could not be prosecuted because of the territorial limitations of the Act. That set Poff off on a one-man campaign to extend the reach of the Espionage Act to the entire globe.

The Espionage Act thus became global, ensnaring anyone anywhere in the world into the web of U.S. jurisdiction.

Monday: The Pentagon Papers

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @unjoe