Part two of a six-part series on Julian Assange and the Espionage Act.

Read: Part One.

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

The 1917 U.S. Espionage Act under which Assange is charged is descended from the 1889 British Official Secrets Act. The Espionage Act replaced the 1911 U.S. Defense Secrets Act, which was based on Section 1 of Britain’s legislation, the Official Secrets Act of 1889.

The language of this section of the Defense Secrets Act is in places nearly identical with the Official Secrets Act. Some of that language has survived in the Espionage Act to ensnare Assange.

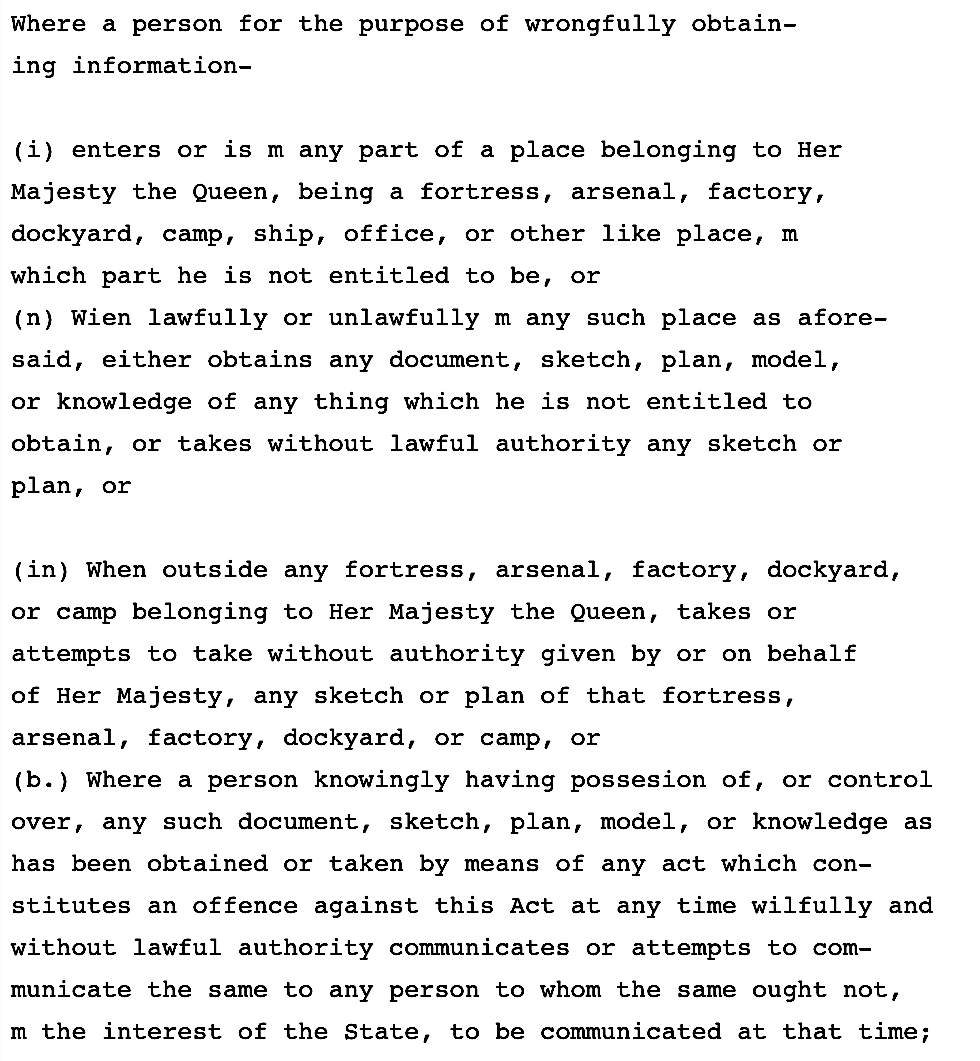

The 1889 British Official Secrets Act says:

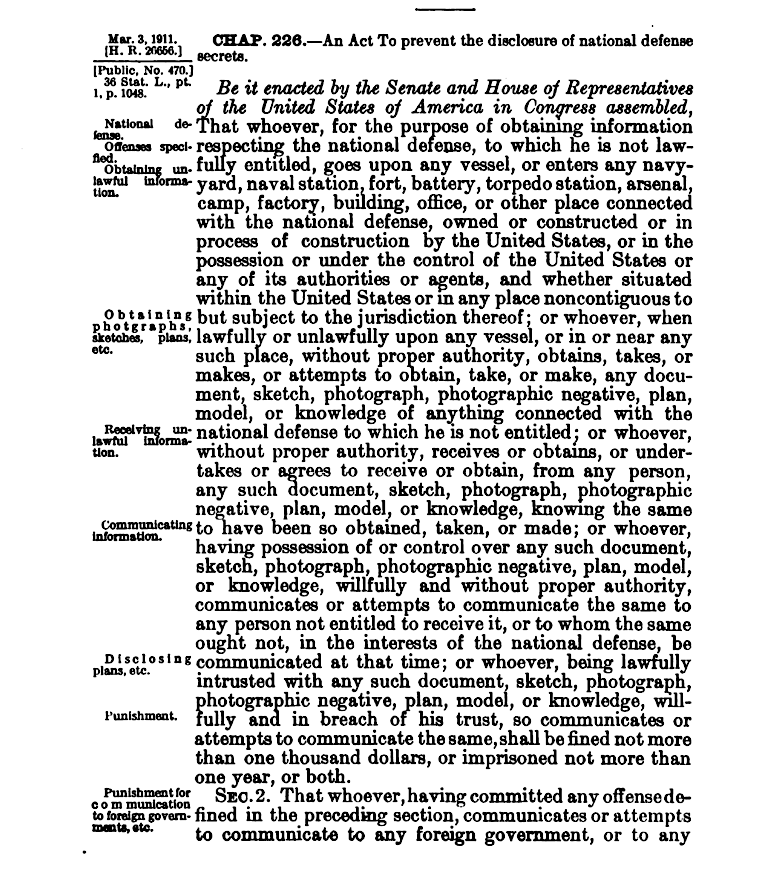

While the 1911 U.S. Defense Secrets Act says:

1889 Official Secrets Act

The 1889 Official Secrets Act was enacted in the midst of continuing unrest in Ireland and British tension with Russia over Afghanistan, hyped by exaggerated press reports of Russian designs on British India. It was also an era of freelance British spies abroad in the empire. The Act came 16 years after the establishment of the Intelligence Branch at the British War Office. Prior to 1889, larceny was the only law against obtaining and disclosing government secrets.

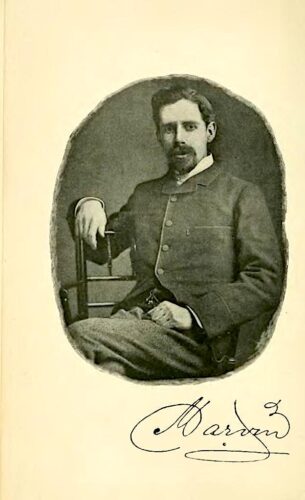

One of the cases that may have led directly to the Act was that of Charles Marvin, a clerk at the Foreign Office, who supplemented his income by freelancing articles to a newspaper. In one 1878 piece he reproduced from memory a secret British treaty with Russia, but the case against him was dismissed because he never physically removed the document from the Foreign Office. If Marvin were indeed the catalyst for the Official Secrets Act, it can be said that it came about to stop a journalist in the future from illegally obtaining and publishing state secrets.

The 1889 Act “is a classic piece of Victorian legislation, clear in some ways, vague in others, but significantly more liberal than what followed,” said Consortium News legal analyst Alexander Mercouris. “Section 1 of the 1889 Act is clearly concerned with spying, though the language is sufficiently vague that in theory it could be stretched to include other forms of disclosure. However I doubt that Victorian judges would have allowed it to be used for purposes other than prosecuting genuine acts of spying.”

Significantly, the 1889 Act included an explicit public interest defense, but only for government employees.

“Where a person, by means of his holding or having held an office under Her Majesty the Queen, has lawfully or unlawfully either obtained possession of or control over any document … at any time corruptly or contrary to his official duty communicates or attempts to communicate that document … to any person to whom the same ought not, in the interest of the State, or otherwise in the public interest, to be communicated at that time, he shall be guilty of a breach of official trust.” (Emphasis added.)

The public interest defense was added to the bill after objections were made in Parliament that the Act might penalize disclosures of government corruption and misconduct.

Section 1 of the Act criminalized any person for mere unauthorized possession and even unauthorized “knowledge” of any secret information (this clearly to prevent memorization of secrets, as Marvin had done). It also made it a crime to communicate such information to an unauthorized person. Even an attempt to do these things was a crime. Assange would have technically been liable under this part of the Act without a public interest defense, as he is not a government employee.

Charles Marvin. (From his 1883 book The region of the eternal fire; an account of a journey to the petroleum region of the Caspian. London, W.H. Allen & Co. University of California Libraries, digitalized by MSN Books.)

Section 2 related only to government officials, who would be guilty of a breach of trust if that official “corruptly or contrary to his official duty communicates or attempts to communicate that document, sketch, plan, model, or information to any person to whom the same ought not to be communicated at that time.”

Anyone “inciting” or “counseling” another person to commit an offense under the Act could also be prosecuted. First introduced here, the offense of “incitement” has survived in the current U.S. Espionage Act and was part of the charge against Assange, who is accused of having “knowingly and unlawfully obtained and aided, abetted, counseled, induced, procured and willfully caused [Chelsea] Manning to obtain documents…”

Jurisdiction of the 1889 Act was limited to “Her Majesty’s dominions,” though government officials could be prosecuted for violations anywhere in the world. Mere possession and communication were misdemeanors, while passing state secrets to a foreign nation was a felony.

This first espionage law, which formed the basis of all such laws that would follow in the U.S., Britain and the Commonwealth (including the espionage law in Assange’s native Australia) made it a crime (even for the press) to possess state secrets without authority and to communicate those secrets. Subsequent versions in Britain and the U.S. refined and reinforced this basic theme, with some important changes.

1911 U.S. Defense Secrets Act

Before the 1911 U.S. Defense Secrets Act, the only U.S. laws against espionage were those relating to treason, theft of government property and unlawful entry onto a U.S. military base.

Just three paragraphs long, the language contained in the Defense Secrets Act is closely aligned with the Official Secrets Act. Section 1 of the DSA covers any person “obtaining” defense information “to which he is not lawfully entitled.” Anyone who “receives or obtains” such information “without proper authority” also broke this law.

A person who “willfully” and without authority “communicates or attempts to communicate” such information to “any person not entitled to receive it” was in breach of the Act. Section 2 spells out a ten year prison sentence if secrets were passed to a foreign government.

1911 Official Secrets Act

In October 1909 the Secret Service Bureau was created by the Foreign Office, the War Office and the Admiralty to deal primarily with “an extensive system of German espionage.” The bureau was split into the domestic service, MI-5, and foreign, MI-6. Both agencies today acknowledge that the German espionage scare that led to their creation was mostly media hype. The MI-5 website says:

“‘Refuse to be served by a German waiter’, the Daily Mail advised its readers. ‘If your waiter says he is Swiss, ask to see his passport.’ Such alarmism reflected the tensions caused by the Anglo-German naval arms race and the approach of the First World War. Most of the ‘spies’ who persuaded Whitehall that it was faced with ‘an extensive system of German espionage’ in Britain were figments of the media and popular imaginations.”

Nonetheless, just two years after the bureau’s creation, and six months after the passage of the U.S. Defense Secrets Act, the British parliament reenacted in a single day after one hour of Commons debate its revised Official Secrets Act on Aug. 22, 1911. MP Sir Alpheus Morton said it was “very unusual and a very extraordinary thing to pass such a Bill without an opportunity of discussing it. Although I do not wish to insist upon the point, I submit that all the stages of a Bill ought not to be dealt with in this House without a proper opportunity of discussing every Clause.”

Removed from the 1889 Act was the explicit mention of a public interest defense.

The 1911 Official Secrets Act also added an alarming Section 2, which was not discussed at all in Parliament or the press before passage, saying it was no longer necessary to prove one’s guilt — the appearance of a crime was enough.

“(2) On a prosecution under this section, it shall not be necessary to show that the accused person was guilty of any particular act tending to show a purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State, and, notwithstanding that no such act is proved against him, he may be convicted if, from the circumstances of the case, or his conduct, or his known character as proved, it appears that his purpose was a purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State…”

Section 1 of 1911 OSA applies to “any person” who “obtains or communicates” a state secret “calculated to be,” “might be” or is “intended to be directly or indirectly useful to an enemy.” This extraordinarily broad language criminalized any person who merely “approaches or is in the neighbourhood of, or enters any prohibited place within the meaning of this Act” for any “purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State.”

The burden of proof shifted to defendants from prosecutors who no longer had to prove the 1889 requirement that the defendant’s motive was prejudicial to the state. Any official document that was obtained was deemed “prejudicial to the interests of the state … unless otherwise proved.” This went beyond anything in the Defense Secrets Act.

Reception of a secret was a crime by any person “unless he proves that the communication to him of the sketch, plan, model, article, note, document or information was contrary to his desire.” A 1920 amendment to the Act made “wrongful communication or retention of official documents” an offense — the first time “retention” was mentioned and made a crime in a U.S. or British espionage law. This led Viscount Burnham to warn during the amendment’s House of Lord’s debate:

“I do not know a single editor of a national paper who from time to time has not been in possession of official documents which have been brought into his office, very often not at his own request, and which it may be inconvenient to the Minister of the responsible Department should have gone out.”

Sir Donald Maclean MP argued in the House that the amendments threatened a free press. “I find it difficult to confine my language in regard to this Bill within the range of Parliamentary propriety. It is another attempt to clamp the powers of war on to the liberties of the citizen in peace,” he said.

Though the main intention of the Act was geared towards foreign espionage, the term “any person” in these two British and one American Act in no way excluded the prosecution of a journalist, the subject of a 1938 London conference on the “Freedom of the Press and the Challenge of the Official Secrets Acts.”

In a speech to the conference, Dingle Foot, who would later become a member of Parliament and solicitor general, said: “These Acts now constitute a sort of statutory monstrosity abrogating nearly all the usual rules for the protection of accused persons and there is nothing to compare with them anywhere else in our criminal law.”

Although Assange was the first indicted under the U.S. law, British journalists had already been indicted for publishing state secrets. In 1971 reporters and editors at The Sunday Telegraph were prosecuted under the 1911 Official Secrets Act for publishing Foreign Office documents about British policy in the civil war in Nigeria. The government lost at trial as the material was shown to have been merely embarrassing to the government.

In 1978 two British journalists were indicted under the 1911 Official Secrets Act in the so-called ABC Trial for publishing an article in the magazine Time Out about wiretapping by the signals intelligence agency GCHQ. Section 1 charges were dropped by the judge at trial for being “oppressive in the circumstances,” but the two journalists, John Berry and Duncan Campbell, were convicted in the Old Bailey under section 2, though they received minimal sentences.

The anti-German mania, which was the backdrop to both the U.S. Defense Secrets and British Official Secrets Acts — passed within six months of each other in 1911 — helped set the stage for the Great War and for the Espionage Act.

Tomorrow: Passing the Espionage Act.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @unjoe