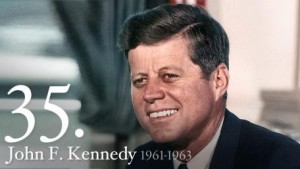

The half-century anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s murder has prompted retrospectives on his presidency but also remembrances of what the shocking act meant to people who lived through it. Journalist Richard L. Fricker reflects on how that day changed his life.

By Richard L. Fricker

This is the day we all knew was coming. Frankly, I am amazed to be here to see it arrive, the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963, in Dallas. Thousands of people are writing their remembrances of that day and, with a little indulgence, I would like to provide you with mine.

Some background: I am Roman Catholic. I have always been a working journalist, as I was that day 50 years ago. The Catholic part first. I was attending Tulsa’s Bishop Kelley High School the year Kennedy was elected. It was the year Kelley opened, combining Marquette and Holy Family into one diocesan high school.

It was here that I met the fellow who would be a lifelong friend, even though our lives would take very different paths. Gary Dotterman’s personality is a force to be reckoned with on any day. Besides the excitement of a new school and lots of new faces, there was also the excitement of one of our own, an Irish-Catholic, not only actually nominated for president, but had a chance of winning. We all knew Al Smith, the Democratic governor of New York, had been the “first” Catholic to run for president.

We knew Smith had lost. He lost by a 58.2 percent to 40.8 percent margin of the popular vote against Republican Herbert Hoover. Hoover garnered 444 electoral votes against Smith’s 87 votes. We also knew Smith’s religion had been a big factor in the election.

Religion was certainly a factor in the Kennedy election. Rumors of the most absurd nature floated around the campaign. Oklahoma was a hotbed of allegations: the Vatican Swiss Guard would take over the FBI, Catholics couldn’t be trusted because the Mass was in a secret language [all masses were in Latin at the time], and any number of assertions that made no sense. We were all confronted with such questions and claims.

We were also aware of what it meant to be a minority in Oklahoma. In addition to bizarre claims, there was the basic prejudice against Catholics in Oklahoma at that time. And there was the Ku Klux Klan that had harangued Catholics, set fire to Catholic homes and businesses, and even to businesses who hired Catholics.

Much of this is chronicled in the 1984 University of Oklahoma publication “Women of the Ku Klux Klan in Oklahoma in the Twenties” by Dr. Laurie Croft, University of Iowa. The Klan, as we knew, was color blind. In addition to African-Americans, Catholics and Jews were targets of their terror.

For high school students emerging into the ‘60s, the election of John F. Kennedy brought fresh air, daylight and promise. His presidency was labeled by the media as “Camelot.” President Kennedy was taking us to the “New Frontier.”We were packed and ready for the journey, or so we thought.

The Day

Flash forward: On Nov. 22, 1963, I was working at a radio station KDSO in Mansfield, Louisiana, while awaiting orders to the U.S. Navy that Dotterman had talked me into enlisting. [Coming from a Navy family it didn’t take much talking.] It was a small 1,000-watt daytime station that covered most of the northern Louisiana’s Desoto Parish. The station was so small it didn’t have a wire service. Any regional news was taken from monitoring the larger stations in Shreveport 40 miles to the north.

I was stumbling my way through an air shift when a woman called asking if it were true the President had been shot. Radio stations are always getting calls from people wanting to verify rumors; I had never received a call of this magnitude. I told the woman I would check and let her know. I walked back to the Shreveport monitor.

It was all true. Even though I was hearing it on network radio news, it was hard to believe. I noted the pertinent information, sat in my chair, took a breath, opened the mic and said, “President John F. Kennedy has been shot.”

I don’t remember what else I said. For a kid working at a radio station in a remote small town in Louisiana, the biggest thing in my media life was to sound like a real announcer; to be the one to tell a community the President had been shot was the last thing on my mind. In fact, that someone would shoot my President never occurred to me, or millions of other Americans. I don’t remember much after making the announcement except a flurry of phone calls to the station.

Later? Lost in a haze. The announcement of Kennedy’s death escapes me, everything was on automatic. At home, after sign off, there was just a feeling of disbelief and loss. There was also a feeling of being alone. I remember thinking, “Why? Who? What comes next?” We had been left on the edge of the New Frontier without our leader.

Kennedy, the sailor, once said, “Any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction: ‘I served in the U.S. NAVY.’”

My Navy orders arrived and by March 1964 I was a fleet sailor aboard a cruiser. I would later learn Dotterman had been stationed aboard a destroyer. We met only once, in Olongapo, Zambales, Philippines. And that is a story for another time.

In retrospect, the ‘60s started the day my President was killed. Kennedy told us, ask what we could do for our country. On that day in 1963, we had no idea the sacrifice and courage it would take to carry that vision forward. Less than a year after the walls of Camelot had been breached, Dotterman, I and thousands of others, too young to drink or vote, would become veterans of the Vietnam War.

There are other milestones and events since that day. But it all started Nov. 22, 1963, 50 years ago. Or, perhaps in that 2 a.m. of the soul, it was only yesterday.

Richard L. Fricker lives in Tulsa, OK and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. His latest book, The Last Day of the War, is available at https://www.createspace.com/3804081 or at www.richardfricker.com .

Oswald did not make any lucky shots that day; but Jack Ruby did.