Without greater equality, Herman Daly, the pioneer of ecological economics, helped us understand that the environment has no real shot at renewal, writes Sam Pizzigati.

Ecological economist Herman Daly speaking at a conference in 2015. (Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

By Sam Pizzigati

Inequality.org

![]() Great thinkers, down through the ages, have regularly had to watch the movers and shakers of their epochs shrug off their core insights. One of our contemporary great thinkers who suffered that fate — the 84-year-old economist Herman Daly — died last month.

Great thinkers, down through the ages, have regularly had to watch the movers and shakers of their epochs shrug off their core insights. One of our contemporary great thinkers who suffered that fate — the 84-year-old economist Herman Daly — died last month.

Daly did not, to be sure, go totally unrecognized during his lifetime. In 1996, he won the “alternate Nobel Prize,” Sweden’s annual Right Livelihood Award.

“Herman Daly redefined economics, forging a way forward that does not include the destruction of our environment for economic gain,” Ole von Uexkull, Right Livelihood’s executive director, noted after Daly’s passing.

But that passing has, by and large, gone unnoticed, at least in the major media, with no obit appearing until well after his death.

Despite this media disinterest, Daly most certainly does figure to get much more attention in the years ahead. Why? The life’s work of this University of Maryland emeritus professor just happens to directly link the two supreme challenges of our time: environmental collapse and economic inequality.

Herman Daly pioneered the discipline of ecological economics. He gave us a vision — in works always “crystal clear, conceptually compelling” — of a “steady state economy” that featured “redistribution and qualitative improvement instead of perpetual growth” sure to overload and overwhelm our environment.

Having Enough

We need, Daly believed, to reject “having ever more” and revolve our lives instead around having enough, and that means sharing, a virtue today, he observed, often derided as “class warfare.” But real “class warfare,” Daly noted a decade ago, “will not result from sharing, but from the greed of elites who promote growth because they capture nearly all of the benefits from it, while ‘sharing’ only the costs.”

And how could we arrive at a “steady state,” at an economy that develops qualitatively, not quantitatively? At one point, Daly spelled out a “top 10” list of policies to move us forward in that direction. High on that list: a call to limit the range of inequality by setting both a minimum and a maximum income.

And how could we arrive at a “steady state,” at an economy that develops qualitatively, not quantitatively? At one point, Daly spelled out a “top 10” list of policies to move us forward in that direction. High on that list: a call to limit the range of inequality by setting both a minimum and a maximum income.

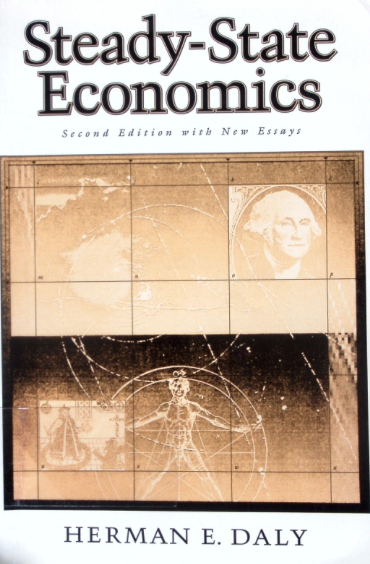

Daly first advocated for this coupling in his 1991 book Steady-State Economics. He contrasted his “min-max” to the conventional economics notion that the poor don’t get hurt when the rich get richer and may actually end up benefiting from the expenditures wealthy people make.

“I argue to the contrary,” Daly wrote in his 1996 book Beyond Growth, “that there is a limit to the total material production that the ecosystem can support, and that it would be clearly unjust for 99 percent of the limited total product to go to only one person. I conclude, therefore, that there must implicitly be some maximum personal income.”

What maximum would be most appropriate?

“A range of inequality permitting a factor-of-ten range difference between the richest and poorest would serve the need for legitimate differences in rewards and incentives,” Daly explained, “while respecting the fact that we are persons-in-community, not isolated, atomistic individuals.”

“No one is arguing for an invidious, forced equality,” he added. “A factor of ten in inequality would be justified by real differences in effort and diligence and would provide sufficient incentive to call forth these qualities.”

But Daly didn’t see anything “sacred about a factor of 10” and felt a factor of 20 could serve just fine. And he saw the Income Equity Act proposed by then Minnesota congressman Martin Sabo — legislation that would limit the tax deduction a corporation could take for executive compensation to no more than 25 times the income of the corporation’s lowest-paid worker — as a step in the right direction.

A point of reference: Last year, the Economic Policy Institute reports, American corporate CEOs averaged 399 times the pay of our nation’s typical workers.

Maximum Wealth & Income

In Daly’s work as a whole, declare Hubert Buch-Hansen of the Copenhagen Business School and Max Koch of Sweden’s Lund University, we find “the most systematic consideration of maximum caps on wealth and income.” In that consideration, Daly didn’t limit his rationale for maximums to economics. The “sense of community” central to successful democracies, he argued, will always be “hard to maintain across the vast income differences current in the United States.”

“Rich and poor separated by a factor of 500 have few experiences or interests in common,” he continued, presciently adding, “and are increasingly likely to engage in violent conflict.”

Daly spent a half-dozen years of his career as a senior economist at the World Bank, and he would regularly place his advocacy for equity within a framework that might resonate within the economic mainstream.

“Private property,” he recurringly reflected, “loses its legitimacy if too unequally distributed.”

Daly also had a gift for explaining his economic precepts with vivid metaphors. Would our economy simply collapse if we no longer had grand rewards to incentivize ever more economic growth?

“The failure of a growth economy to grow is a disaster,” Daly explained in an interview this past July. “The success of a steady-state economy not to grow is not a disaster. It’s like the difference between an airplane and a helicopter. An airplane is designed for forward motion. If an airplane has to stand still, it’ll crash. A helicopter is designed to stand still, like a hummingbird.”

“The failure of a growth economy to grow is a disaster,” Daly explained in an interview this past July. “The success of a steady-state economy not to grow is not a disaster. It’s like the difference between an airplane and a helicopter. An airplane is designed for forward motion. If an airplane has to stand still, it’ll crash. A helicopter is designed to stand still, like a hummingbird.”

Daly spelled out concepts like these in a series of remarkable works that started nearly a half-century ago with a 1973 essay collection entitled “Toward a Steady-State Economy.” This body of work, unfortunately, would gain “little attention in the economic mainstream,” and governments today, as analyst Paul Abela quips, “are hardly forming an orderly queue seeking to embrace” Daly’s egalitarian steady-state approaches.

But Daly’s work has nurtured a new generation of economists who understand that success in a steady-state economy, as Abela reminds us, “would not be based on maximising profits and increasing GDP but rather on maximising human well-being.”

“In the coming decades, weather extremes will start to wreak havoc on our ability to provide the goods and services needed to provide for people’s needs,” he sums up. “In the midst of it all, Daly may well gain the widespread acclaim and reverence his ideas deserve.”

[Related: COP27: Oxfam Sizes Up a Single Billionaire’s Investment Emissions]

That acclaim, sadly, didn’t come in Daly’s lifetime. But that lack of recognition never punctured his good cheer and hopeful optimism that his economics profession would one day understand why we need to see the world through a different economic lens. That optimism comes through loud and clear in one of Daly’s last published works, a foreword to a widely acclaimed new Daly biography by the Canadian economist Peter Victor.

“I used to be a neoclassical growth economist,” Daly wrote. “I hoped that my contribution to the world would be to help increase the growth rate of GDP, especially in the poor regions of Latin America, but in wealthy countries too. But experience, arguments, and evidence changed my mind, and I became an ecological economist who advocates a steady-state economy with redistribution and qualitative improvement instead of perpetual growth.”

“Might not the same happen to other economists?” Daly went on. “Indeed, is it not now happening, although slowly? Why won’t the same evidence and logic that has convinced me (and a number of others) eventually convince many more?”

Let’s hope that evidence and logic turn out to have just the impact that Daly so indefatigably envisioned.

Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win: The Forgotten Triumph over Plutocracy that Created the American Middle Class, 1900-1970. Twitter: @Too_Much_Online.

This article is from Inequality.org.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

“What maximum would be most appropriate?

“A range of inequality permitting a factor-of-ten range difference between the richest and poorest would serve the need for legitimate differences in rewards and incentives,” Daly explained, “while respecting the fact that we are persons-in-community, not isolated, atomistic individuals.”

“No one is arguing for an invidious, forced equality,” he added. “A factor of ten in inequality would be justified by real differences in effort and diligence and would provide sufficient incentive to call forth these qualities.”

Very essential!

To get back to urgently required balance.

Socially, ecologically, and last but not least economically.

New Rule: No one shall be allowed to be a billionaire whilst any human being on the planet does not have security of food, water, education, a home, and participation in political decisions.

First, let us strive for that.

100% tax on wealth and income amounting to over one billion dollars. 51% ownership by the people, for every corporation worth over a billion. A progressive scale to that point.

After that, once everyone is fed and clothed, housed and literate, medically supported and ecologically sustainable, then we can have a debate about who’s “merit” deserves opulence or privileged status. Once every new child has health and education everywhere, then we can debate who “deserves” more and for what reason.

Presently, we all work together to ensure the wealth and privilege and political power of the people who already have these things, and this process requires poverty for many… so, poverty is a required and inflicted circumstance for many, to ensure opulence for a few. Those few are in charge, and they make the rules for everyone else.

Still though, no one ought to be a billionaire until no child in the world goes hungry. Really simple concept.

This socioeconomic structure makes this goal impossible. There must be many poor people, somewhere, for there to be rich people at all. Relative poverty and inequality compounds into violent suppression very quickly.

I think Picketty wrote about how inequality grows because existing inherited wealth grows faster than new productive wealth can be created. It’s a cumulative advantage which prevents social mobility… and even on an international scale.

Having billionaires and hungry people at the same time, is systemic failure.

he sounds like a very decent man who doesn’t seem to mention capitalism by name which is the system causing all the problems he clearly mentions..maybe he read marx but didn’t like his punctuation? at any rate, steady state, socialist state or communist state, if democracy that is global doesnlt come into existance very soon we will all face something even more devastating than a collapsed state.

Anyone studying mathematics has wondered how Leibnitz and Newton independently discovered calculus at practically the same time. If we posit that ideas can “be in the air”, so that lots of people perceive and think them at important times, then Daly’s principles are “in the air” today, and just as there are subtle differences in the two calculeses, the ideas of sustainable ecology and degrowth will be elaborated and refined to produce something that works.

Otherwise, humanity is doomed.

I don’t believe it’s naive to state that we have accepted the lesser of evils for so long such that the system has become totally corrupted. We have become acclimated to the corruption like Orwell’s proles in his “1984.” Kurt Vonnegut wrote “There is no reason good can’t triumph over evil, if only angels will get organized along the lines of the Mafia.” Our government has rationalized Mafia methods and tactics on a global scale, and most of us remain oblivious.

It absolutely blows the mind how impervious to reason and propagandized the American public has become due to a concerted effort that the wealthy have undertaken mainly since the 1970s.

Daly was not only a generational thinker, but (and they properly go together) a generous human who would take the time to correspond with someone like me, answering questions and encouraging my own investigations.

Thank you for this short, cogent introduction to Herman Daly’s work. While I knew his name and his attachment to environmental /sustainable economics, your piece has made me want to search out and read more of his work.

I always take a bit of umbrage when a rigorous scientific discipline like ecology which confronts testable hypotheses with evidence is associated with the naval-gazing pseudoscience of economics. What theories with predictive power have “ecological” economists produced that are relevant to the real world? Fictions that require special pleading like the “Environmental Kuznets Curve”?

Caution in thought is important, but can be over done as preciousness. Both ecology and economics are fundamentally concerned with oikos; that is the important focus, not so much the details of the epistemological difficulties of disciplines.

Ecological economics must be anti-capitalist, as capitalism goes up in smoke without continual growth. Surprising that capitalism wasn’t mentioned in the article. I wonder whether Daly talked about it.

Might be the best, not to mention something obviously unsustainable and destructive, but presenting something better straight away ;)

And a discussion about it is possibly avoided ^^

How do his ideas differ from those of Michael Hudson?

Structural change is essential to the survival of life on earth. Daly has gifted us with a path toward a sustainable system. We would be foolish not to do all we can to bring his enlightened “Steady State” system to fruition.

Never ever will steadiness be reached as long as economists reasoning within the borders of the economy (money, money, money) are the ones to guide us out of the desert since the cause of all the wrong originates in civil law.

This “Steady State Economics” is similar in principle to the path China is on in its economic, political and social humane planning.

m.e. cardella, Seattle, WA

Bless you. I am following Michael Hudson, know little about economics, but know when the majority are hurting, something is wrong. Hudson outlines it differently and in my humble opinion, easier to understand, and further more links financialization and privatization to the US’s murderous drive to capture other countries resources and the politicians and leaders that go along with US.