Consortium News begins today a six-part series on Julian Assange and the Espionage Act.

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

From its earliest years the United States has found ways to deny the rights of a free press when it was politically expedient to do so.

One of the latest ways was to arrest WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange 29 months ago on April 11, 2019 and to indict him — the first time a publisher and journalist has ever been charged under the 1917 Espionage Act for possessing and publishing state secrets.

Though several U.S. administrations had come close to punishing journalists for revealing defense information, they all pulled back, until Assange. They were restrained because of a conflict with the First Amendment, which prohibits Congress from passing any law, including the Espionage Act, that abridges press freedom.

Until that legal conflict is resolved in court, resulting in parts of the Espionage Act being found unconstitutional, the language of the Act threatening press freedom remains. Bolstered by 1950 amendments to the Act, the Donald Trump administration crossed a redline to arrest a journalist. A 1961 amendment made it possible to indict a non-U.S. citizen, acting outside U.S. territory.

The Trump administration’s first indictment of a publisher opened an alarming precedent for the future of journalism.

President Joe Biden’s Department of Justice has not reversed Trump’s move to continue to seek Assange’s extradition from Britain though it could have. Instead it decided on Feb. 13 to pursue the appeal of Judge Vanessa Baraitser’s decision not to extradite Assange to the U.S. on health grounds. If the U.S. should win on appeal, Assange will be brought to the Eastern District of Virginia to face 17 Espionage Act counts, amounting to 175 years in prison, as Baraitser challenged none of those counts in her judgement.

Threats to press freedom are an integral part of U.S. history. Assange’s arrest and indictment comes within a long line of government repression of a free press, first by the British against American colonists, and then by the U.S. government, which based the Espionage Act on the British Official Secrets Act.

Possession and Dissemination

Assange did not pass state secrets to an enemy of the United States, as in a classic espionage case, but rather to the public, which both the U.S. and British governments might well consider the enemy.

Assange revealed crimes and corruption by the state. Punishing such legitimate criticism of government historically amounted to a charge of sedition, but two sedition acts were repealed in the U.S. shortly after they were made law and are no longer on the books.

Other journalists and publishers in the past have been prosecuted under the Espionage Act, but mostly for criticizing and trying to curtail the military draft during the First World War.

Assange became the first journalist prosecuted under sections of the Act that make it a crime to have (or even attempt to have) unauthorized possession of defense material, and separately, to communicate it, since technically neither he nor anyone working for WikiLeaks were authorized to do so.

The language used in his indictment based on the Espionage Act is so broad that theoretically anyone who has shared a classified WikiLeaks publication on social media could also be liable to prosecution, not to mention the many mainstream media organizations that routinely report on and quote from classified material, including from WikiLeaks.

The overly broad language means the government does not generally have to prove that the intent was to harm the U.S., only that a defendant, in this case Assange, knew it could.

Neither does the possession and publication of classified information have to cause any actual harm to the U.S. The government does not need to prove that publication actually threatened national security.

Intent, Retention, Communication & Person

The main issues involving Assange’s Espionage Act indictment and the history of Anglo-American espionage legislation are: a) intent: whether motive is relevant to prosecution and whether a public interest defense is possible; b) person: who is liable for prosecution, whether only government officials, normally the source of leaked secrets, or anyone, including journalists who publish them; c) retention: whether mere unauthorized possession is a crime; and d) communication: the laws as they have regarded unauthorized communication of defense information.

These four aspects of espionage laws on both sides of the Atlantic evolved in numerous complex ways over the century between 1889 and 1989, in particular how they have affected journalism. But earlier governments also found ways to choke off press freedom.

A History of Prosecuting Speech

While Assange is the first journalist indicted for possessing and disseminating classified information there is a long history of prosecuting speech in America.

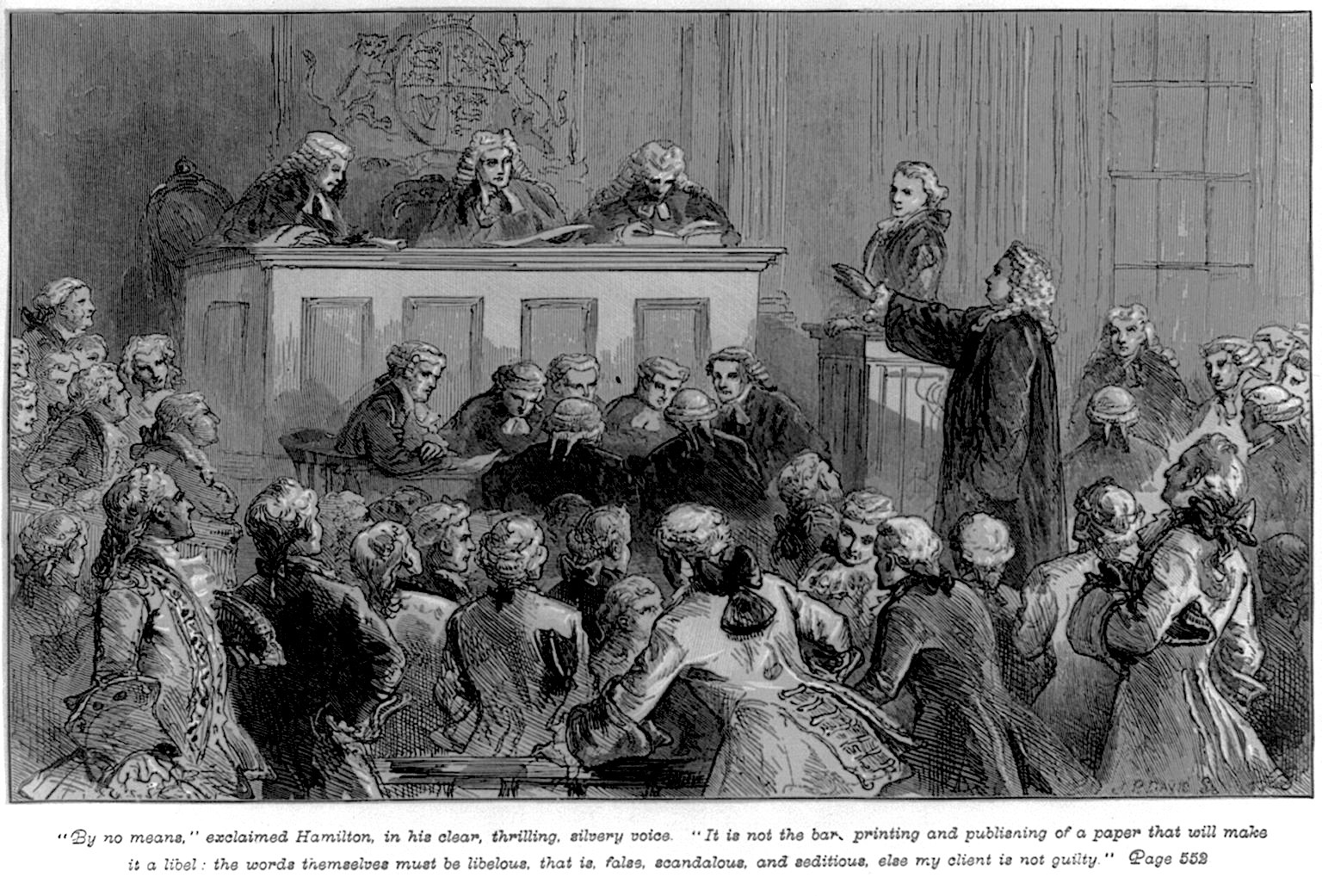

The classic case of a publisher being prosecuted for publishing material critical of a government authority, on the territory of what would become the United States, took place in 1735 in the British colony of New York.

William Cosby, the governor of the colony, put John Peter Zenger, publisher of The New York Weekly Journal on trial for printing an article accusing Cosby of rigging elections and other corruption.

Though the judge ordered that Zenger be found guilty based on the libel law at the time (which criminalized criticism of the government even if true) the jury acquitted Zenger, arguing that the law was unjust. This historic case of jury nullification paved the way for the First Amendment after the American Revolution.

“Morris called Zenger’s case ‘the germ of American freedom … which subsequently revolutionized America.’”

If Assange were to be extradited and go on trial in Alexandria, Virginia, a jury ignoring the Espionage Act’s repressive restrictions on press freedom could be Assange’s best hope for freedom. Such an event could also pave the way for a successful constitutional challenge of the law on First Amendment grounds.

Genesis of First Amendment

The Zenger case was referred to 52 years later in the 1787 U.S. Constitutional Convention by Gouverneur Morris, a New York signer of the Declaration of Independence. Morris called Zenger’s case “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.” One of the many parts of British common law American rebels opposed was that truth was no defense in a libel case.

Though the Virginia colonial legislature had passed a Declaration of Rights in 1776 that included the line, “The freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic Governments,” and though eight of the other 12 colonies passed similar language, there was resistance to this and other parts of a declaration of rights being adopted at the Constitutional Convention.

After more than three years of debate, the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution in December 1791. The first of these rights says:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

1798 Sedition Act

Just eight years after the adoption of the Bill of Rights, press freedom had become a threat to John Adams, the second president, whose Federalist Party pushed through Congress the Alien and Sedition Laws. They criminalized criticism of the federal government:

“To write, print, utter or publish, or cause it to be done, or assist in it, any false, scandalous, and malicious writing against the government of the United States, or either House of Congress, or the President, with intent to defame, or bring either into contempt or disrepute, or to excite against either the hatred of the people of the United States, or to stir up sedition, or to excite unlawful combinations against the government, or to resist it, or to aid or encourage hostile designs of foreign nations.”

Congress did not renew the Act in 1801 and President Thomas Jefferson pardoned prisoners serving sentences for sedition and refunded their fines.

Prosecuting the Press in the US Civil War

Freedom of the press next came significantly under attack in the lead up to the 1860-65 U.S. Civil War. Newspaper editors who campaigned for the abolition of slavery were attacked by mobs, sometimes directed by elected officials. More than 100 mobs attacked abolitionist newspapers. In 1837 an editor was killed by a mob, one of whose organizers was the Illinois attorney general.

During the war numerous editors and journalists were arrested in the North. “Throughout the war, newspaper reporters and editors were arrested without due process for opposing the draft, discouraging enlistments in the Union army, or even criticizing the income tax,” according to the First Amendment Encyclopedia.

Grand juries in New York and New Jersey presented a list of newspapers condemned for calling the conflict an “unholy war.” The Post Office was ordered to stop delivering those newspapers and “U.S. marshals in Philadelphia seized copies of the listed newspapers as they arrived by train.”

The encyclopedia says,

“In the vast majority of instances, the government restrained the free press without any legal process. The military routinely arrested newspaper editors and closed their presses; military tribunals banished some of them to the Confederacy for encouraging resistance.”

Secretary of State William Seward ordered the arrest of an editor from the Freeman’s Journal for allegedly treasonous statements and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton “authorized a military governor to destroy the office of the Sunday Chronicle in Washington.”

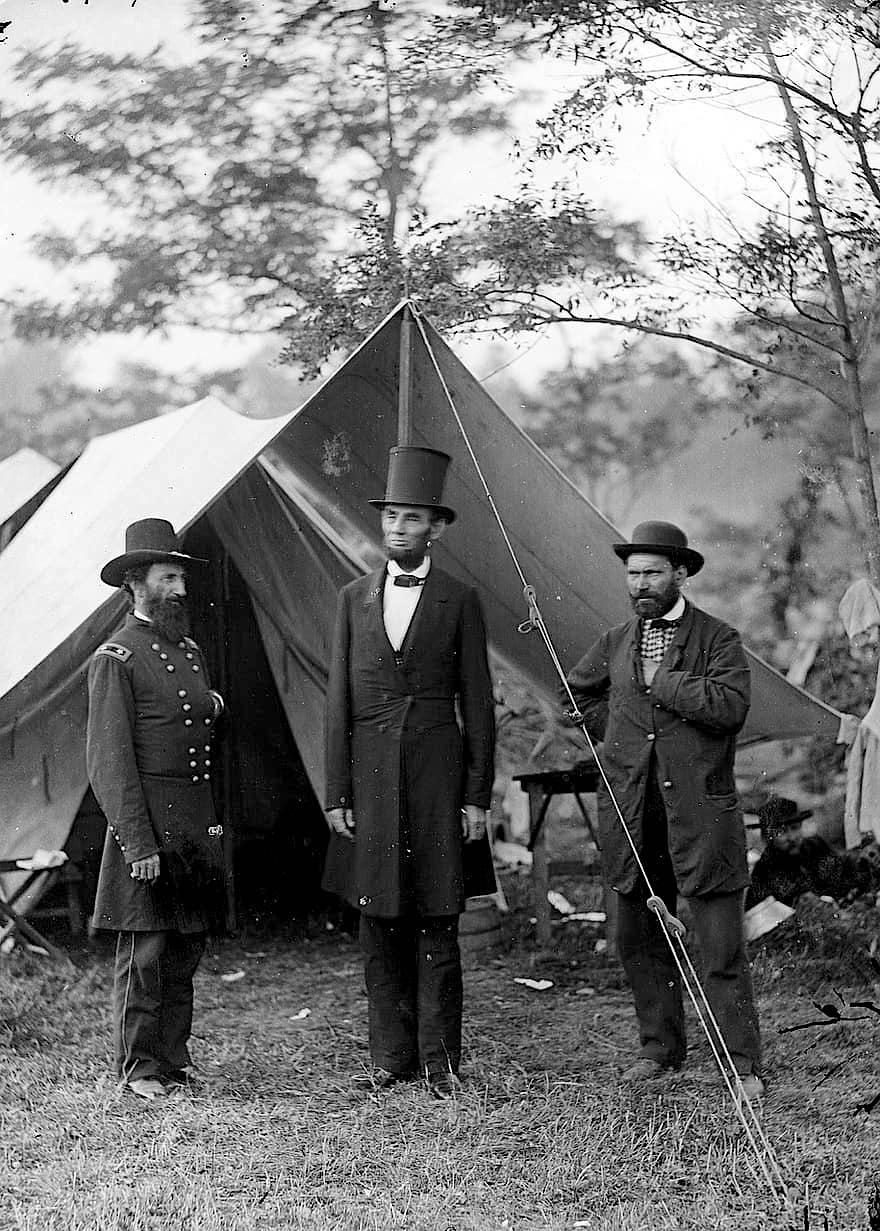

Allan Pinkerton, Lincoln and Gen. John McClendand. (Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921 – 1940 Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 – 1985)

President Abraham Lincoln was faced with a dilemma, which he posed in a July 1861 speech: “Must a government of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?” In trying to strike a balance, Lincoln reversed an order by Gen. Ambrose Burnside to suspend the Chicago Times and criticized Gen. John Schofield for arresting the editors of the Missouri Democrat.

The greater concern was that Confederate generals read Northern newspapers to learn of Union troop movements, an issue that would appear 50 years later in the Espionage Act. In 1862 Lincoln set up military trials for people agitating against the military draft, an issue that would also be later codified into the Act.

Tomorrow: The Espionage Act’s UK Origins

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

From the article: “The overly broad language means the government does not generally have to prove that the intent was to harm the U.S., only that a defendant, in this case Assange, knew it could.”

And this: “Neither does the possession and publication of classified information have to cause any actual harm to the U.S. The government does not need to prove that publication actually threatened national security.”

Says it all to me of where we stand, legally, in the world today as a government supposedly of, for and by…

Overly broad language the better to sweep with as wide a net as desired? When intention is disregarded is that also a way of disregarding plain text in bill of rights? It would seem so when considered among other ongoing tendencies such as to shut up, lock up, beat up those who would peaceably assemble & freely express themselves in opposition to misuse of authority.

With reams of data on everyone conveniently sifted out of the ether (as we slumber under its dizzying effect), how hard would it be to design cherry-picking algorithms to stitch-up a story to put any dissenter in the dock?

And what if the U.S. government is itself the harm? If publishing real evidence of that harm is considered the threat? Does that not grant an open-ended opportunity for tyranny?

Thanks, CN, for keeping whatever pressure you can muster on this grievous wound.

This is the history I want to read. This is the news we need to read. We all need to know why free speech and especially Journalism are so very important to ths functioning of democracy.

Thanks Joe.It is very enlightening reading your article associated with Julian Assange. I am an avid follower of writers and I thank you and the like minded writers and publishers and hold to account unscrupulous authorities who use clauses of the , with intent to defend their tirany to defend themselves against any thruth writing against these authorities. Julian Assange a writer and publisher and have exposed in the media for public interest,that war is futile,crimes against the innocent people must be be brought to Justice, not hide it.Free press is a Right of of a conciencious journalisms, Free Press is an Humanitarian act and Human Right Act.It must be protected. The Truth and the Justice will Prevail.FREE ASSANGE.

Free Julian Assange Now.

“Without a Free Press, there can be No Democracy”

Thomas Jefferson