Special Report: Amid the trivia of American politics, voters can forget that they are entrusting the winning candidate for President with the nuclear codes, the power to annihilate all life on the planet, a reality that reporter Don North witnessed up close a half century ago in the Cuban missile crisis.

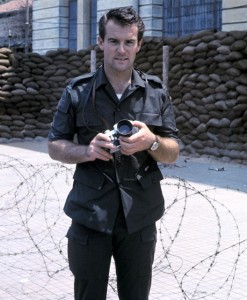

By Don North

Saturday, Oct. 27, 1962, now known as “Black Saturday” was the day I arrived in Havana to report on the Cuban missile crisis, completely oblivious that 50 years later it would be considered “the most dangerous moment in human history,” the day we came closest to nuclear Armageddon.

My rendezvous with this existential crisis began on Oct. 22, in a New York bar where I had arranged to meet friends and incidentally to watch a TV address by President John F. Kennedy that was supposed to have something to do with Cuba. I had visited Cuba as a freelance journalist six months earlier and was fascinated by the country.

Kennedy’s TV address was a shocker. “Unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island,” Kennedy said looking grim. A hush fell over the bar and waiters stopped serving to hear his words.

After 50 years of study and analysis we now know that in addition to the nuclear-armed missiles, the Soviet Union had deployed 100 tactical nuclear weapons which the Soviet commander in Cuba could have launched without additional approval from Moscow.

A U.S. naval blockade of Cuba had begun the day before Kennedy’s speech. “A strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated,” the President said.

As Kennedy spoke the U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) had gone to DEFCON-3, (Defense Condition Three) two steps down from nuclear war, and dispersed its nuclear-armed bomber fleet around the United States. The Cold War had suddenly grown hot.

A truthful history of those dark days was the first casualty. Although tape recordings of White House meetings on the crisis were made, they were kept classified until ten years ago, as many of the participants worked to burnish or obscure their position at that time. Bobby Kennedy made a pre-emptive strike on history by writing and publishing his book, Thirteen Days, a self-serving recollection of the crisis.

We now know that JFK’s covert war against Cuba dubbed “Operation Mongoose,” a campaign of harassment and sabotage had contributed to the war of nerves that led the Russians to step in to the defense of Cuba. However, as transcripts of the taped White House meetings of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (ExComm) would reveal when declassified decades later, JFK used cool political skill and all his intellect to prevent a possible nuclear war.

As he told the ExComm members, as he ordered the dangerous naval blockade to go into effect, “What we are doing is throwing down a card on the table in a game which we don’t know the ending of.”

The taped record of how JFK played his hand trying to contain the chaotic forces of history in the face of unyielding pressure from hawkish advisers like Generals Curtis Le May and Maxwell Taylor shows the crisis was a supreme test of the President’s ability to maintain an open mind, while holding to his entrenched abhorrence of war.

It is a cautionary tale to remember as we fear a possible future showdown with a nuclear-armed Iran and are about to choose a President in an election 50 years after the missile crisis of October 1962. Sound judgment and emotional stability can make the difference between a peaceful compromise and a catastrophic war.

Hugh Sidey, a journalist who was a friend of Kennedy and covered the White House for Time magazine at the time of the crisis, had this to say in appraising JFK’s leadership: “Once in the Presidency there is virtually no time for re-education or introspection that might show a President where he is right or wrong and bring about a true change of mind. Events move too fast. A President may pick up more knowledge about a subject or find an expert aide on whom he can rely, but in most instances when he is alone and faced with a crucial decision he must rely on his intuition, a mixture of natural intelligence, education, and experience.”

Self-Assigned to Havana

Although a few weeks earlier I had finally landed a job as a news writer on the NBC evening news, I was ready to chuck it for the opportunity to report from a key city during the missile crisis where few foreign journalists were based. I walked across the street from NBC studios in Rockefeller Center to the Life magazine office.

Room with a view: Havana’s Malecon seafront as seen by Don North from his window on the ninth floor of The Capri hotel where he and other journalists were held during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Although I hadn’t worked for Life before and only owned an inexpensive Kodak, I was ushered in to see a senior editor and was immediately loaded down with several Leica camera bodies, an assortment of lenses and a brick of fast 35mm film. Life didn’t have a man in Havana and for this story they would risk taking a chance on a youthful broadcast news writer with some Cuba contacts willing to travel into ground zero for American ICBM’s and bombers.

“Don, you’re our man in Havana now,” said the editor in a well-cut gray suit. “Get some good shots, write some snappy cut lines and give us the story of Havana at the center of the storm.”

New Yorkers were scared. Newspapers carried illustrations of New York and Washington as targets within the range of the Soviet ICBMs now operational from Cuba. Lines formed at grocery stores and gas stations. Friends made plans to drive their children to relatives’ homes in less vulnerable areas of the country.

My sister Helen had recently arrived from Canada to work as a nurse at the Roosevelt Hospital in central Manhattan. We shared a small apartment. I was reluctant to leave her alone in a city perhaps facing a devastating enemy attack. Her hospital was already planning for handling casualties.

My first stop was Miami to consult with my friend Miguel Acocca, Time magazine’s man in the Caribbean. Miguel said I had two choices. The first was to link up with the U.S. Second Marine Division preparing landing craft in Key West for an invasion of Cuba. It would be called Operation Scabbards and be comparable to the Normandy landings in 1944. It would involve eight divisions, around 120,000 troops, and land on a 40-mile front between Mariel and Tarara Beach, east of Havana.

Or my second choice was to try to get on a Cubana Airlines flight left outside Cuba when the blockade went into effect, that would be returning to Cuba in the next few days from Mexico City.

I knew Mario Garcia-Inchaustigi, the Cuban ambassador in Mexico. We had shared many a rum and coke at the Delegates Lounge in the United Nations when he was the Cuban delegate and I was an announcer for U.N. General Assembly sessions. If there was any chance of a visa and a ticket on that flight, Mario could arrange it. I cabled the Embassy explaining my situation and took the next flight to Mexico.

With a visa in hand, purchasing a ticket on the Cubana flight was easy. The only passengers confirmed were members of an East German soccer team. Boarding the flight I was aware from monitoring recent radio broadcasts that it was a sensitive time to be arriving in Havana. The first Soviet ship to test the American blockade, the Grozny, was reported about to encounter U.S. Navy ships.

Earlier, in a radio broadcast Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had warned, “if the United States carries out the piratical actions, we shall have to resort to means of defense against the aggressor to defend our rights.”

Along with the youthful soccer team from East Berlin, there were five other international journalists on board the flight: a fellow Canadian Robert MacNeil of NBC; Gordian Troeller, a Luxemburger and his wife Marie Claude, both working for the German magazine Der Stern; Atsuhiro Horikawa, Washington correspondent of the Japanese Yomiuri Shimbun, a Tokyo daily; and Alan Oxley, a British freelancer who worked for CBS News and lived in Havana.

Not Welcome in Havana

Walking from the plane into the dark, hot, humid Havana air was not unpleasant and costumed guitarists strummed a welcome as we entered the passenger terminal. A giant poster declaring that Cuba was “en pie de Guerra” (on war alert) graced the terminal building.

Message gone awry: A letter listing the names and nationalities of detained journalists is dropped from the ninth floor of The Capri hotel but lands on a guard outpost causing the arrest of two of North’s friends.

Inside, men in battle fatigues with side arms or carrying machine guns eyed arriving passengers suspiciously. My visa was stamped and I was directed to an adjacent room where my fellow journalists were being held. In a few minutes, soldiers with machine guns at the ready ordered us in Spanish to take our luggage and board an army truck waiting outside.

We were driven to the center of Havana to a small, modern hotel called The Capri. The officer in charge informed us politely in English that we were to be “guests of the Cuban government.” We were given room keys and escorted under armed guard to rooms on the ninth floor. Two guards with machine guns were posted outside our rooms.

The Capri Hotel was located in the heart of downtown Havana, a few blocks from the Havana Hilton and the old Hotel Nacional. I lay in my bed trying to sleep but kept thinking about a U.S. Pentagon study of nuclear war effects on different size cities. If the worst happened overnight and U.S. ICBMs dropped a one megaton bomb on Havana, it would vaporize my hotel leaving a crater 1,000 feet wide and 200 feet deep. The blast would destroy virtually everything within a 1.7 mile radius.

Of the two million inhabitants hundreds of thousands living in central Havana would be killed instantly. Tens of thousands more would die of radiation within hours. Fires would rage across the rest of the city as far as the Soviet military headquarters in El Chico, 12 miles from city center.

But confined to our hotel, we were oblivious to the momentous events unfolding on Black Saturday:

–A U.S. Air Force U-2 reconnaissance aircraft had been shot down while on a mission to photograph the Soviet missiles. The pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed.

–A U.S. Air Force U-2 accidentally strayed into Soviet airspace near Alaska and Soviet interceptors gave chase.

–Defense Secretary Robert McNamara reported the Soviet ship Grozny was steadily approaching the Cuban quarantine line.

–Six low level U.S. “Crusader” reconnaissance flights had been forced to turn back by Cuban ground fire while photographing missile sites.

–The U.S. Navy located and dropped practice depth charges to force four Soviet “Foxtrot” nuclear armed submarines to surface.

–The Soviet Union and the United States both conducted atmospheric nuclear tests on this day.

–Two Cuban exiles dispatched by the CIA under the Mongoose program had set explosive charges at the Metahambre copper mine in Pinar Del Rio. The two were captured by Cuban police.

Any one of these incidents could have provoked a nuclear response in the tense “eye-ball to eye-ball” atmosphere that prevailed that day. Twenty-four Soviet SAM sites were now operational.

But there were stories within each of those stories. For instance, the CIA flew slightly better U-2’s than the U.S. Air Force; they had a more powerful engine and could fly 5,000 feet higher. President Kennedy preferred to have Air Force pilots flying over Cuba than CIA pilots as fewer questions would be asked if they were shot down. The CIA reluctantly agreed to lend several of its U-2’s to the Air Force and they were repainted with Air Force insignia.

As one U-2 approached the missile site at Banes, in Western Cuba near Guantanamo, an order came from Soviet military headquarters in El Chico near Havana, “Destroy target number 33. Use two missiles.” A proximity fuse detonated the SAMs as they closed in, spraying shrapnel and killing Major Rudolf Anderson instantly.

Declassified Soviet sources have confirmed the missile was not cleared to fire by the Kremlin. Furious, Krushchev ordered no further firings take place without his direct orders. In Washington, Air Force Gen. Curtis Le May ordered rocket-carrying fighters readied for an attack on the SAM site. The White House ordered Le May not to attack unless he had direct orders from the President.

“He chickened out again,” Le May growled. “How in hell do you get men to risk their lives when the SAMs are not attacked?”

Thousands of miles away, a U-2 flying out of Eielson Air Force base in Alaska on a mission to monitor air samples during the Soviet nuclear test that day became disoriented and flew some 400 miles into Soviet airspace. The pilot was Captain Chuck Maltsby.

The Soviets could well have regarded this U-2 flight as a last-minute intelligence reconnaissance in preparation for nuclear war. Soviet MIG aircraft tried to intercept the U-2 flying at 75,000 feet but could not reach that altitude. Alaskan Command sent up two nuclear armed F-102 interceptors to protect the U-2.

When President Kennedy was later told about the incident he replied, “There’s always some sonofabitch who doesn’t get the word.”

Six U.S. Navy “Crusaders” flying at tree-top level under Soviet radar headed westward to photograph the missile sites of Pinar Del Rio. Antiaircraft guns manned by Cuban crews opened fire as the Crusaders approached the San Cristobal missile site. The pilots, aware of multiple hits, aborted the mission and flew home to Key West.

Soviet submarine commanders were highly disciplined and unlikely to trigger their nuclear torpedoes by design, but we now know the unstable conditions on board the subs raised the specter of an accidental nuclear launch. U.S. Navy ships had located four Soviet “Foxtrot” submarines lurking in the waters south of the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Each day the subs had to surface to charge their batteries and report to Moscow. Once located the subs were forced to surface by U.S. Naval ships dropping hand grenades and practice depth charges.

On “Black Saturday,” Oct. 27, 1962, one sub B-59, commanded by Captain Valentin Savitsky, had been chased for two days. His batteries were low and he had not been able to communicate with Moscow. Temperatures in the sub reached as high as 140 degrees, food was spoiling in the refrigerators and water was low and rationed. Carbon dioxide levels were becoming critical and sailors were fainting from heat and exhaustion.

Submerged several hundred feet the sub came under repeated attack from the USS Randolph dropping practice depth charges. The explosions became deafening. There is no greater humiliation for a submarine captain than to be forced by the enemy to surface. Forty years later, a senior sub officer on B-59, Vadim Orlov, described the scene as Captain Sevitsky lost his temper.

“Savitsky became furious. He summoned the officer in charge of the nuclear torpedo, and ordered him to make it combat ready. ‘We’re going to blast them now,’ said Savitsky. ‘We will perish ourselves, but we will sink them all. We will not disgrace our Navy.” Fellow officers persuaded Savitsky to calm down and a decision was made to surface in the midst of four American destroyers.

A Spy and Journalist Out of Their Depth

In Washington, a Russian KGB officer and an ABC News reporter inserted themselves in the drama. Aleksandr Feklisov, the KGB station chief, had approached ABC News State Department correspondent John Scali with a plan to dismantle missile bases in Cuba in return for a U.S. pledge not to invade. Scali ran it past Secretary of State Dean Rusk and got his approval.

Their meddling was a classic case of miscommunication between Washington and Moscow at a time when a misstep could have led to nuclear war. By Scali’s account it had been a Soviet initiative. Feklisov presented it as an American one. What Scali thought was a feeler from Moscow was in reality an attempt by the KGB to measure Washngton’s conditions for a settlement.

Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin said he had not authorized this type of negotiation and refused to send Feklisov’s messages to Moscow. Feklisov could only send his negotiation report with Scali by cable to KGB headquarters. There is no evidence the cable was ever read by Khrushchev or played any part in Kremlin decision-making. Yet, the Scali-Feklisov meetings would become part of the strange mythology of the Cuban missile crisis.

I later came to know Scali as a very undiplomatic diplomatic correspondent given to outbursts of temper. I was a correspondent for ABC News in Vietnam and not supportive of the war. Scali was a hawk whose Vietnam visits were choreographed by President Lyndon Johnson and Gen. William Westmoreland. He often trumpeted his role as mediator in the missile crisis and was later named U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations by President Richard Nixon.

Before “Black Saturday” ended President Kennedy got more bad news. The CIA determined for the first time that five out of six medium-range missile sites in Cuba were fully operational. With the sand in the glass almost gone that evening, Kennedy sent his brother Robert to meet with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to warn him U.S. military action was imminent. At the same time, Krushchev was offered a possible way out. Pull his missiles out of Cuba and the U.S. would promise not to invade and also withdraw missiles from Turkey.

Radio News

In Havana, our Japanese colleague Horikawa had a powerful Zenith shortwave radio and we spent a lot of time Sunday listening to news broadcasts from Miami. Khrushchev had “blinked.” Moscow radio broadcast a long letter Khrushchev wrote to Kennedy agreeing to remove the missiles from Cuba under U.N. inspection. Kennedy in return agreed not to invade Cuba. The crisis between the world’s superpowers was waning. However, Fidel Castro was furious over the settlement and felt betrayed by his Soviet friends.

We continued to be his guests. We were fed regularly, but monotonously from the hotel kitchen. It was mostly “arroz con pollo,” chicken with rice. It helped to wash it down with Bulgarian red wine at $5 a bottle. And to make meals an even more festive occasion we ordered Cuban cigars and Russian Vodka at a nominal price in U.S. dollars. Periodically on the Miami NBC radio station, it was reported that six international journalists who had flown into Havana had not been heard from and were considered “missing.”

On Monday, another day passed and no one came to see us. The guards did not communicate. We spent a lot of time trying to be journalists, jotting in our journals whatever we could observe from our room windows. Looking down toward the harbor, we could see a lot of ships, including Soviet freighters that had passed through the blockade.

On the Malecon, the seaside street, we could see an anti-aircraft battery manned by Cuban soldiers. Regularly, U.S. Navy “Crusader” reconnaissance planes flew over our hotel very low. But we never saw the anti-aircraft battery engage them as the speedy jets screamed overhead.

Platoons of “milicianos,” male and female civilians on military duty, often marched through the streets in view of our hotel. On Cuban radio or even the hotel sound system, patriotic music interrupted by urgent announcements of news bulletins and excerpts from speeches of Fidel kept the country charged up for war. Cubans were told regularly to expect an invasion by the United States.

Whoever was in charge seemed to have forgotten about us. We were never mistreated, but simply held incommunicado. From the first day we began plotting ways to draw attention to our dilemma.

One afternoon I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw two old friends from my childhood in Canada drinking at an outdoor café just below my window. Doug Buchanan and Rod McKenzie were pilots for International Air Freighters flying Toronto to Havana. We hastily wrote a letter addressed to the Havana Associated Press office listing our names, nationalities and the circumstances of our house arrest and tossed it through the window louvers to the old friends lurking below.

As fate would have it, the letter floated down nine stories and came to rest on the roof of a guard post below. The two pilots perhaps emboldened by rum and cokes climbed up to the roof of the guard post to retrieve the letter, whereupon the guards seized them and marched them off at gunpoint.

The next day, Alan Oxley, the British journalist whose home was Havana, spotted a girlfriend in a bikini sunning herself on the roof of an apartment building adjacent to our hotel. Alan shouted to her to bring her baby and try to visit us in the hotel. Within an hour she arrived pushing a baby buggy and the guards allowed her in to visit with Alan. Before she left we slipped the letter to AP into the baby’s diaper but the crafty guards searched on the way out and found the letter.

Phone Home

The following day, Horikawa, the Japanese journalist suggested a new plan to make contact with the outside world. The phones in our rooms were all dead, shut off at the switchboard. We screwed off the plates in the wall where the phone wires entered and found a gathering of multicolored wires. With a razor blade we slit each of the wires and inserted the phone terminal connections.

Our theory was that by trial and error we would eventually tap into wires connected to another room and the call would register at reception as coming from another room. We intercepted conversations in Russian, Spanish and Chinese, before finally tapping into phone lines of an empty room. At last we got a dial tone and called the number for the Associated Press. The AP already knew who we were, but promised to contact the Embassy of each of us being held.

All the wires were somehow jammed back into the wall as if they had never been tampered with. It was just in time, as the hotel manager and receptionist came to the ninth floor and ordered the guards to inspect an empty room where they claimed telephone calls were being made. Later that day, the Miami radio station reported our names and that we were being held under house arrest in The Capri.

‘Shove Ha’penny’

Still no one came to visit and time passed very slowly. Robert MacNeil, who had recently come from assignment in London, had a pocketful of British half pennies and introduced us to the popular pub game in Britain called “Shove Ha’penny.” It involved hitting a half penny with your palm and sending it into a pattern of lines on the table. First person to fill the rows wins the game. We played for hours.

On our fourth day of confinement, Oct. 30, we heard on the radio that Castro had rejected the Washington-Moscow settlement. U Thant flew in to Havana to attempt to persuade him but failed. Three days later, on Nov. 4, the Soviets sent in their prime negotiator, Anastas Mikoyan, to reason with Castro. By then, we had been under house arrest for nine days.

Free at Last

Raul Lazo, a young junior officer at the Cuban Foreign Ministry, quietly called on us that evening and simply said we were free to go and report as we liked. “I hope you will forgive us for having detained you. Please understand the crisis made it necessary,” he said.

To celebrate our freedom, Robert MacNeil and I checked out the thriving nightclub in The Capri, whose loud music had kept us awake while under house arrest. The big Havana hotels still featured lavish floor shows, typical of pre-revolutionary decadence with leggy dancers in brief costumes. Tables were crowded with well-dressed couples drinking rum or vodka. The air was heavy with aromatic Cuban cigar smoke.

Enjoying our first night of freedom we took a late night stroll that took us past the Havana TV station. A large black limousine pulled up and out stepped Commandante Che Guevara wearing army fatigues, his signature beret with a red star and a large Cohiba cigar clenched in his teeth. Che had been in his military headquarters in a limestone cave in Pinar Del Rio throughout the crisis. This was his first night back in Havana. A small group of admirers quickly surrounded him and he signed a few autographs.

I approached with my flash camera and said, “Por favor, Commandante.” Che smiled without removing his cigar and I shot a close-up head shot against the night background. (Later at home in New York, the photo when processed was sharp and clear and I fancied becoming a millionaire from poster and t-shirt sales. Alas, the color slide of Che later went missing when an airline lost my suitcase.)

Lively bars with bands and dance floors were open late that night. Robert and I took a table and ordered a final Daiquiri to toast our freedom. A friendly waiter discovered that we were Canadian journalists. A few minutes later a spotlight hit our table as the master of ceremonies said, “Bienvenidos, amigos periodistas Canadianse.”

Then, the spotlight swung to a table just behind us. “Bienvenidos, companero sovietico,” said the announcer. Sitting in the spotlight was Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the famous Russian poet. We sent him a drink and introduced ourselves. Yevtushenko was working on a heroic film about Castro. He had written a poem that would appear on the front page of Pravda, the Moscow daily:

America, I’m writing to you from Cuba,

Where the cheekbones of tense sentries

And the cliffs shine anxiously tonight

Through the gusting storm.

A tabaquero with his pistol heads for the port.

A shoemaker cleans an old machine gun,

A showgirl, in a soldier’s laced-up boots,

Marches with a carpenter to stand guard.

America, I’ll ask you in plain Russian;

Isn’t it shameful and hypocritical

That you have forced them to take up arms

And then accuse them of having done so?

I heard Fidel speak. He outlined his case

Like a doctor or a prosecutor.

In his speech, there was no animosity,

Only bitterness and reproach. America, it will be

difficult to regain the grandeur that you have lost

Through your blind games, While a little island,

standing firm, became a great country.

First thing Monday morning all six of us who had been held in The Capri turned up at the Foreign Ministry as instructed to obtain press credentials so we could cable or phone our reports. We were told the officials responsible for press accreditation were out of town and to try again “mananna.”

Dangerous Company

On my first trip to Havana, in March 1962, I had met Larry Lunt, a friendly American who owned a large ranch called Finca San Andres in Pinar Del Rio province, about a hundred miles west of Havana. He had been very helpful to me and had brought me along to many Embassy parties. I spent several weekends as his guest at the ranch.

Larry was a World War II and Korean War veteran and had been a rancher in Wyoming until moving to Cuba in 1955. He had not been a fan of Batista and was pleased when Castro took over in 1959. Soon he was appalled by Fidel’s move to Communism, but in conversations with me did not harshly denounce the regime or its ruinous economic policies. I repeatedly called a number I had for Larry’s apartment in Havana. It never answered and I assumed he was at his ranch without a phone.

The maxim that a person is known by the company he keeps is especially true in Cuba. In numerous trips to Cuba as a journalist and a tourist I always assumed the phones in my hotel were bugged, but I never felt I was under surveillance. Certainly Larry Lunt was under surveillance when I befriended him in March 1962. Unknown to me Larry Lunt was a CIA agent.

I read a newspaper in 1965 that reported Lunt had been arrested and imprisoned in Havana. There were no other reports that came to my attention until I learned of a book he had written and published in 1990 Leave me my Spirit. It’s a remarkable memoir of Lunt’s 14 years in a Cuban prison and his work as a CIA agent.

Lunt had been recruited and trained by the CIA before moving to Cuba. Under the agency’s guidance, he bought the farm as a base for secret operations. In his book, Lunt described running numerous Cuban agents who were in a position to provide intelligence. His ranch covered hundreds of acres and was ideal for air drops of saboteurs, arms, explosives and ammunition. He had provided early reports that the San Cristobal missile site photographed by U-2’s in October 1962 was a Soviet intermediate-range missile site.

Each month, Larry relayed a report from one agent who was an engineer at the Matahambre copper mine near his ranch. The mine produced 20,000 tons of copper a year, mostly for export to the Soviet Union. The CIA in its “Operation Mongoose” unsuccessfully tried to sabotage Matahambre 25 times. Even during the October crisis, two agents who had planted bombs at the mine were captured by Castro forces.

In 1979, Lunt was released and deported in an exchange of prisoners. Many spies in Cuba had been executed for lesser crimes than Lunt. However, his book is an eloquent view of inhuman conditions in Cuban prisons and of his unconquerable spirit that helped him to survive.

Pacifying Fidel

Every day we assembled at the Foreign Ministry in quest of Cuban press cards and every day we were told to try again tomorrow. Fidel was furious with his Soviet friends for caving in to U.S. demands and had even rejected a Soviet proposal for international inspection. U Thant had come and gone from Havana, and on Nov. 2, Krushchev’s principal deputy Anastas Mikoyan arrived in Havana to persuade Fidel to agree to inspection and removal of the Ilyusian-28 bombers.

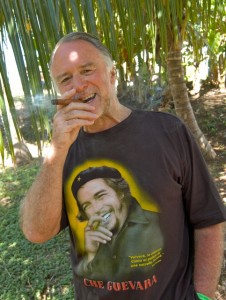

Don North during a recent trip to Cuba commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Castro grudgingly met Mikoyan’s plane, but refused to meet with him for days. At the bar of the Havana Libre Hilton, I chanced to meet a Canadian pilot who had flown in with Mikoyan’s plane. In 1962, Canadian pilots were required on flights out of Gander airport in Newfoundland. He would be pleased to keep me informed on Mikoyan’s schedule and planned departure date which would indicate his tough negotiations with Castro were over.

The Hilton bar was probably the most conspicuous watering hole in Havana and again if Cuban intelligence was noticing the company I kept, it would not enhance my daily request for a press card.

One of the most well-informed and influential diplomats in Havana was Dwight Fullford, second secretary at the Canadian Embassy. I learned he had pressed the Foreign Ministry hard for my release from house arrest. On the fourth evening after my release from the hotel, Dwight and his wife Barbara invited me for dinner at a popular Havana restaurant. We had just met on a street corner and Dwight excused himself to buy cigarettes.

Standing on the corner talking with Barbara, I was astonished to see a black limousine pull up and two men in suits jump out. They grabbed me forcefully, shoved me into the car and in a screech of tires sped away leaving Barbara to explain the sudden disappearance of their dinner guest. Dwight, like the responsible diplomat he was, went back to the Embassy to again work the phone lines on my behalf to the Foreign Ministry.

I was taken to a small jail near the harbor which was used for immigration cases. Within an hour most of the journalists held in The Capri had been rounded up and again became guests of the government, this time in a grimy cell. The next morning a diplomat from the Canadian Embassy dropped by to say the Cubans had decided to deport us to Mexico, the only place Cubana Airlines was flying that week.

There was a hitch. The Mexicans had refused to receive supposed criminals from a Cuban jail. The diplomat said he was working on it.

The next three days passed slowly behind bars. We scratched our names and the date on the cement wall along with thousands of other past prisoners. A young Nicaraguan who spoke excellent English said his name was Raul and tried to engage us in constant conversation. He was obviously a government plant and we regaled him with glowing admiration for the Cuban revolution, Fidel and Che, hoping he would report on us favorably.

There was a TV set mounted high on the wall that we could view through the bars. Each evening of our stay they broadcast a serial based on Ernest Hemmingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. In his later years Hemmingway had lived in Havana and his books were still popular there.

One morning our luggage that we had left in the hotel when we were seized was brought to our cell. Nothing seemed to be missing from mine, but books, letters and private papers had notes pinned to them with Spanish translations written on stationery of the Cuban Security police. For some reason I had brought along a small song book from the University of British Columbia, my alma mater. Several of the songs, like a Scottish drinking song, had been labeled as secret code.

The next morning, the head guard announced we would be released later that day. However, pointing at the substantial beard I had grown since arriving in Cuba, he said, “Senor North, before you can be released you must shave your beard. In Cuba only Fidelistas have beards and you’re not a Fidelista.”

I protested but he was adamant. No shave, no freedom. A dull Gillette was produced with no shaving soap or hot water and with a gun in my back I stood at the sink and painfully shaved.

Mexico had agreed to issue transit visas and we were booked on a flight to New York leaving two hours after our arrival. We were deported without ceremony.

Summing Up Fifty Years

Perhaps the best book looking back on the dark days of October 1962 is One Minute to Midnight by journalist Michael Dobbs. In summing up how catastrophe was averted, Dobbs wrote:

“Despite all their differences, both personal and ideological, the two men had reached similar conclusions about the nature of nuclear war. Nikita Krushchev and John Kennedy both understood that such a war would be far more terrible than anything mankind had known before. They also understood that a commander in chief could not always control his own armies. In short they were both human beings flawed, idealistic, blundering, sometimes brilliant, often mistaken, but ultimately very aware of their own humanity.”

Despite everything that divided them, they had a sneaking sympathy for each other, an idea expressed best by Jackie Kennedy in a private letter she sent to Krushchev following her husband’s assassination:

“You and he were adversaries, but you were allied in a determination that the world should not be blown up. The danger which troubled my husband was that war might be started not so much by the big men as by the little ones. While big men know the need for self-control and restraint, little men are sometimes moved more by fear and pride.”

In retrospect it is clear the United States needs its President not to be so overdosed with his own testosterone or so obsessed by his own insecurities that he not only understands the meaning of nuance but is actually prepared to conduct relations with the rest of the world in a balanced, thoughtful manner.

Ultimately it means showing the judgment of a John Kennedy rather than the belligerence of a Gen. Curtis LeMay. The danger today may not be as high as in October 1962, but it is not hard to imagine that another nuclear crisis could arise.

In 50 years, we have learned a great deal about the events of October 1962, but do we know the full truth even today? The British think tank, Royal Institute of International Affairs, in writing on this subject concludes:

“We believe that even if we knew every detail about the crisis it would not mean we could write a definitive history, even if that history were to be written from the perspectives of each participant in turn. The reason for this is that motivations and intentions are rarely revealed and are usually inconsistent across time if not at each specific moment.”

In March 2001, at a conference on the missile crisis held in a hotel at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, I interviewed Arthur Schlesinger who had been a close adviser and speech writer for Kennedy at the time of the crisis. Schlesinger told me:

“History is an argument without end. No historian would use the word definitive because new times bring new preoccupations and we historians realize we are prisoners of our own experience. As Oscar Wilde used to say, one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it.”

Don North has covered some of the most dangerous stories of the past half century, including the Cuban missile crisis and conflicts in Vietnam, Afghanistan, El Salvador, Nicaragua and the Middle East. North’s upcoming book, Inappropriate Conduct, will be published in November, the story of a Canadian war correspondent in Italy in 1944 who operated at the risky front line between truth and propaganda in wartime.

Mr. North:

Referring to those Soviet diesel-powered subs………Have you any idea how they were found? Go to the following URL

and find out: http://dool-1.tripod.com/days79.htm

Also get a copy of “First Seal” by Roy Boehm and Charles Sasser available at your local library or at amazon.com

Robert Marble TMCS(SS) USN (Ret)

Mission Viejo, CA

Mr. North,

Thank you for this fascinating story.

As the anniversary of the assassination of JFK is approaching…isn’t it time real reporters such as yourself tell us who really killed Kennedy?

“At the same time, Krushchev was offered a possible way out. Pull his missiles out of Cuba and the U.S. would promise not to invade and also withdraw missiles from Turkey.”

Beside the Iran jingo styled debacle above, can anyone explain why the writer has avoided discussing the back channel?

In truth, it was the US’s way out; and Teddy Roosevelt’s presumptive occupation of the Cuban playground was effectively guillotined.

Hi, One of the best articles on the “DAY WE CAME CLOSET TO NUCLEAR ARMAGEDDON”–

BLACK SATURDAY, 27 OCTOBER, 1962. Note that those two F-102s sent to protect the lost U-2–were armed with NUKE WARHEADS–DEFCON #2. The F-102 is a SINGLE -seater jet. THUS IF THEY HAD TO FIRE NUKES VS. THE SOVIET JETS, THEY WOULD HAVE HAD TO VIOLATE DOD POLICY–ON TWO SIGN-OFFS BEFORE USING NUKES!!IT WOULD HAVE BEEN THE NUCLEAR INCIDENT GENERAL LEMAY was waiting for. ALSO, SOMEONE(AT OFFUT/AFB(?) WAS GIVING ORDERS IN ENGLISH TO THE “LOST” U-2–to turn WEST DEEPER INTO RUSSIA, rather than EAST toward Alaska. Capt. “M”. had the good sense to keep the RUSSIAN MUSIC behind him & reject the AMERICAN VOICES USING HIS CALL SIGN & TRYING TO GET HIM TO FLY DEEPER INTO RUSSIA–AND VERY POSSIBLY WW III/ARMAGEDDON. George E. Lowe [For more details SEE my two VOLS: STALKING THE ANTICHRISTS: AND THEIR FALSE NUCLEAR PROPHETS/NUCLEAR GLADIATORS & SPIRIT WARRIORS–1940–2012. XLIBRIS, FALL 2012]

interesting to see the old anticommunist fear, and to see the present mention of nuclear-armed Iran, as if it were a fact.

rosemerry:

Good catch.

Much better than mine: The misdating of the D Day landings in Normandy. Only significant, in that the mistake calls into question other dates.

One wishes that Mr North had put this text aside for a few days before submitting it.