Author James Douglass, who produced a thoughtful book on President Kennedy’s assassination, has now turned his attention to the murder of nonviolent Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi in 1948, providing rare context for that momentous event, writes Jim DiEugenio.

By Jim DiEugenio

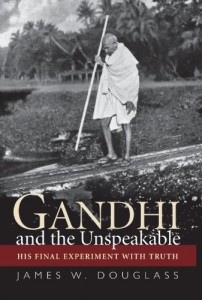

In 2008, James Douglass published one of the best books ever written on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. JFK and the Unspeakable was not your usual Kennedy assassination book, in the sense that it was not primarily a detective story.

It was really a book about President Kennedy’s policies. And through an examination of those policies, it tried to place him in a comprehensive political context. By doing so Douglass’s strategy was not just to define who Kennedy was and what he was up against, but also point out who his enemies were in trying to achieve his foreign policy goals.

It seems odd today that no one had written a book like that before. But Douglass did. And the book did something that few books on Kennedy’s assassination do. It attained crossover appeal.

That is, it did not just appeal to the rather narrow assassination critical community. Since it was about more than the Kennedy assassination, it sold well outside that community. In fact, today, over three years later, it is still a steady seller.

That book was to be the first in a trilogy about the assassinations of the 1960’s. Another was to be based on the murder of Robert Kennedy, and the third was about the killings of both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

Douglass had not planned to write Gandhi and the Unspeakable as a separate book about the death of Mohandas K. Gandhi. He was originally going to integrate that information into the King/Malcolm book. And since, in many ways, King had been a disciple of Gandhi, that would have been quite appropriate.

But Douglass was put in touch with the descendants of the Mahatma. Specifically his grandson, and great grandson, respectively Arun and Tushar Gandhi. The latter had put together a thousand-page sourcebook on Gandhi’s murder entitled Let’s Kill Gandhi: A Chronicle of His Last Days, the Conspiracy, Murder, Investigation and Trial. This was first published in 2007, is extremely rare in the United States, and also expensive. But it is a very impressive work.

Tushar wrote the book because he felt that a pernicious mythology had sprouted up around the assassination. A mythology propounded by the actual conspirators, their allies, and also government forces, who all feared the size and ferocity of the Hindu fundamentalist movement that was behind the murder.

Among the lies were that Gandhi was responsible for the partition of India, that he was pro-Pakistani, and that his philosophy would lead to the dominance of Muslims over Hindus.

Douglass also read the actual trial transcript at the Library of Congress. The third major source Douglass uses is the 1968-69 review of the Gandhi case by the government commission led by Judge J. L. Kapur. This review contains much important information that was not brought out at the trial. For as we will see, for political reasons, the actual trial was something of a stage-managed affair. The object being to protect that actual mastermind of the plot to kill Gandhi.

Through Hollywood’s Lens

What most adult Americans know about Gandhi’s life and death is garnered through the 1982 biographical film called simply Gandhi. British actor/producer Richard Attenborough had been trying to get this movie made for nearly two decades. He once had the illustrious David Lean slated to direct the film with himself playing Gandhi. Unfortunately, that fell through.

Ten years later, Attenborough directed Ben Kingsley as Gandhi from a script by John Briley. Quite naturally, Briley’s script concentrated on Gandhi’s 30-year crusade of civil disobedience to force the British out of India.

Although Briley did depict the young Gandhi in South Africa and he did use the assassination as a framing device to connect the beginning with the end, in retrospect, he shortchanged both episodes. For example, although the mastermind of the Gandhi murder plot is shown in the film, he does not speak, nor is he named. Douglass’s book is a good antidote for this double discounting.

Gandhi was trained as a lawyer in London. He was credentialed in 1891 and moved back to India that year. He could not establish a successful practice. So he decided to take a contract with a large Indian firm in South Africa, also part of the British Empire.

Arriving there at age 23 in May 1893, Gandhi would spend 21 years in South Africa. It was there that he developed his political views, moral compass, and his effective non-violent techniques. In Natal, Gandhi met with instances of overt discrimination. For instance, he was asked in court to remove his turban. He was thrown off a train when he refused to move to the third-class section even though he had a first-class ticket.

It was these and other experiences that galvanized him into a leadership role. He soon developed his own Natal Indian Congress. (Douglass, p. 2) In less than four years, he and this group had become such a thorn in the side of both British rule and the white majority that Gandhi was detained on board a ship when he returned from a vacation in December 1896.

Attorney General Harry Escombe said the ship was contaminated with the plague and therefore must return to India. This forced detention went on for three weeks. A huge crowd began to occupy the dock. Escombe realized he now had a serious problem on his hands, for the crowd had been whipped up so much that they would very likely attack Gandhi and other Indians as they stepped off the boat.

Therefore, Escombe tried to tranquilize the crowd by saying he would now use this incident to push for more restrictions on Indian immigration. (Ibid, p. 4) He then tried to arrange for Gandhi to leave the vessel at night with an escort.

But Gandhi disobeyed this plea. He left the ship during the day and began to walk home alone. As he did so he was first stoned. He was then punched and kicked. He collapsed, but desperately clutched at the iron railings of a house. He was saved by the arrival of Mrs. Jane Alexander, wife of Durban’s police superintendent. (ibid, p. 5) She stood in front of him and shielded him with an umbrella until the police arrived.

He was escorted to a friend’s house. Police Chief Richard C. Alexander advised him to disguise himself as a policeman. He did, and accompanied by two officers, he walked to the police station where he waited 72 hours for mad passions to die down. Escombe was advised by London to prosecute Gandhi’s assailants. But Gandhi refused to press charges. (ibid, p. 6) Gandhi insisted on speaking at Escombe’s funeral (in 1899) and called him a great man.

Defending Indians

In 1906, nine years after being nearly stoned to death, Gandhi addressed a crowd of 3,000 Indians at a theater in Johannesburg. The government of South Africa wanted to make all Asiatics register, be fingerprinted, and carry identification cards. Gandhi decided on a compromise path. He thought the Asians should voluntarily register in return for a promise from Colonial Secretary Jan Christian Smuts to repeal the law.

Because of his willingness to compromise, there was an attempt on Gandhi’s life, this time by one of his followers. (ibid, p. 14) He was beaten and clubbed and left for dead in the street. But he survived.

When he recovered, he learned that Smuts had double-crossed him. He was not going to repeal the law. Gandhi now began his first massive show of civil disobedience. He asked his thousands of followers to burn their registration papers. Eventually, Smuts ending up arresting 4,000 Indians. Gandhi then called for a general strike. (ibid, p. 19)

This proved to be effective at first. But now Gandhi had the problem of feeding tens of thousands of his followers who were not working. Smuts had Gandhi arrested.

At this point, young Gandhi did something very wise. The impact of a nationwide strike of European railroad workers was paralyzing the South African government. Gandhi now announced he would call off a huge march he had arranged since he “would not take advantage of an opponent’s accidental difficulties.” (ibid, p. 21)

This was a brilliant stroke. Now messages of thanks and praise poured in from England, India and even South Africa. Smuts’s secretary admired this move, saying, “I do not like your people, and do not care to assist them at all. But what am I to do? You help us in our days of need. How can we lay hands upon you?” (ibid)

Smuts had come to the same conclusion. In the spring of 1914, he negotiated a settlement with Gandhi. This included the abolition of taxes on indentured servants, non-Christian marriages were now made valid, and the registration act was repealed.

At a huge meeting in Johannesburg, many objected to the settlement. When the crowd got threatening, a tall, husky man stepped forward brandishing a dagger. He looked at Gandhi first. He then turned to the crowd and said, “If anyone harms him, he will fall victim to my dagger.”

He was Mir Alam. This was the man who had almost beaten Gandhi to death for registering in the first place. After the meeting, Mir Alam escorted Gandhi and his co-workers safely to their residence. (ibid, p. 22)

Birth of Anti-Apartheid Movement

As Nelson Mandela later acknowledged, Gandhi’s challenge to Smuts was the beginning of the anti-apartheid movement, for the African National Congress (ANC) had been established during Gandhi’s nine-year organized struggle in South Africa. In fact, it was established in 1912, just two years before Gandhi’s settlement with Smuts.

In 1914, Gandhi left South Africa. Smuts said at the time, “The saint has left our shores. I sincerely hope forever.” (ibid, p. 24) He was correct. Gandhi never returned. But many years later, when Smuts had become Prime Minister of South Africa, he tried to warn his fellow Prime Minister Winston Churchill about Gandhi. He told Churchill that Gandhi was a completely spiritual being. Therefore, he appealed to that aspect in his followers, to the point they would risk their lives for him.

This was a value that he and Churchill did not have. And it was why Gandhi had an advantage over them. (ibid) As we shall see, Churchill did not understand Smuts’s warning. England would now try to maintain dominance in India by a divide-and-conquer strategy: Hindus versus Moslems.

And when Gandhi finally attained independence for India, this strategy would lead to the partition of Moslem Pakistan from Hindu India. Gandhi opposed this policy. It was this opposition that hatched the plot to eliminate him.

Gandhi had known the man responsible for his death for over 40 years. While in South Africa, Gandhi made a fateful journey to London in 1909. Ten days before he arrived, an assassination took place: the murder of William Curzon Wyllie, an aide to the Secretary of State of India.

The man who shot Wyllie was Madanlal Dhingra. But Dhingra was acting under the influence of 26-year-old Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. As Douglass describes him, Savarkar was an “Indian philosopher of violent revolution and assassination.” (ibid, p. 28) He ran a cabal of militant Indian students at a hostel in London called India House.

He had spent months molding Dhingra into an assassin. Previously he had convinced him to kill the actual Secretary of State for India. This had failed. When Savarkar gave Dhingra the revolver to kill Wyllie, he told him: “If you fail this time, don’t show me your face again.” (ibid, p. 29)

Dhingra was such a fanatical follower of Savarkar that he immediately began to cover up his role in the murder. He had said that if he lived and Savarkar died, their cause would never survive. But if he died and Savarkar lived, his cause would live on through other followers.

After Dhingra’s execution by hanging, Savarkar succeeded in getting a statement published in the London Daily News. (ibid, p. 29) The statement was penned by Savarkar but ran under Dhingra’s name. It said that the assassin had consulted no one but his own conscience before committing the murder of Wyllie. Which, of course, was a lie.

Gandhi read all of the reports and watched the aftermath of the assassination drama play out. He actually considered Dhingra innocent of the crime. Gandhi saw Dhingra as a man intoxicated by a destructive idea, and thought that those who incited Dhingra were the ones responsible for the murder of Wyllie.

And Gandhi said, even if the British left India due to assassinations, who would then lead in their place? A band of murderers who happened to be brown instead of white? (ibid, p. 30) He concluded that Dhingra was “egged on to do this act by ill-digested reading of worthless writings.” (ibid)

This last comment was an indirect reference to Savarkar. Gandhi had known the man from a previous trip to London in 1906, when he stayed at India House. In that summer of 1909, Gandhi and Savarkar shared a speaker’s platform in London to present their differing visions for India’s eventual independence. This was done over a subscription dinner at an Indian restaurant on the feast of Dussera, commemorating the victory of good over evil in the classic Hindu epic, The Ramayana. (ibid, p. 31)

Jailing a Fanatic

A few months later, the authorities traced the murder weapon used in another political assassination, this time in India, to Savarkar. (ibid, p. 35) Savarkar got a 50-year sentence for his role in the plot. While in prison, he wrote a letter to the British authorities in India, a plea for clemency based upon his new view of a free India state within the British Empire, something he called an Aryan Empire. (ibid, p. 48)

In response, Savarkar was transferred to a less onerous prison where he became a librarian. In 1923, he was moved again and allowed to teach classes. It was at this time that Savarkar began to preach against the followers of Gandhi who had been imprisoned for civil disobedience.

Since the British now considered Gandhi their chief enemy in India, they were pleased with the “reformed” Savarkar. In an interview with the British governor of Bombay, he accepted his confinement to Ratnagiri district and promised not to engage in political activities. (ibid, p. 49)

After he was released from prison on Jan. 6, 1924, Savarkar compared his negotiation with that of a captured general who realizes he is of no use to his cause in detention. Savarkar did engage in political activities in Ratnagiri, but they were nothing that would disturb the British authorities. He began to teach a Hindu nationalism that was strongly anti-Muslim and had a culturally Hindu view of the world.

K. B. Hedgewar visited Savarkar in Ratnagiri in March of 1925. After this consultation, Hedgewar founded the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a party which eventually became the most powerful in India. Its hallmark was its anti-Muslim stance.

Savarkar wrote a book called Hinduvata: What is a Hindu?, which centered on Hinduism as more of a cultural and political identity than a religious one.

In 1929, postal worker Vinayak Godse was transferred to Ratnagiri. His son, Nathuram, visited Savarkar for the first time. Nathuram’s brother Gopal later wrote, Nathuram then began to see Savarkar often and undertook the work of copying his writings. Savarkar later made Nathuram his secretary and appointed him to a leadership post in the RSS.

In the Thirties, Savarkar helped create the anti-Muslim, military-oriented Hindu Mahasabha organization. He was the president of the group from 1937-44. During World War II, he urged young Indians to join the British in the war effort so they could be “re-born into a martial race” and the war would then “Hinduise all politics and militarize Hindudom.” (ibid, p. 52)

In 1944, Gandhi was about to hold talks with Indian Muslim leader Muhammed Ali Jinnah. A group of young men, including Nathuram Godse, vowed to stop the meeting. They picketed Gandhi’s ashram gates, attempting to block him from attending the meeting.

When the police arrived, they found a knife over a half-foot long concealed on one of the men. (ibid) When the officer asked the man if he had planned on becoming a martyr, he replied that no, that would only happen when Gandhi was assassinated.

The officer then said, why not leave it to the leaders to settle the dispute? Let Savarkar come and do the job. To which the potential assailant responded, this would be to great an honor for Gandhi. He then pointed to a follower of Savakar next to him and said he would “be quite enough for the purpose.” (ibid, p. 52) The man he was pointing to was Nathuram Godse, the future murderer of Gandhi.

Freeing India

No person was more responsible for the independence of India than Gandhi. There is no need to detail some of the mass demonstrations Gandhi arranged, including the brutally suppressed great salt mine march. That incident is depicted in the Attenborough film, and Douglass describes it again. (pgs. 38-44)

The combination of Gandhi’s endless crusade and the depleted British treasury after World War II led to the granting of independence in 1947. But with this came a partition of the country into Pakistan and India. The former was the home state of the Moslems and the latter for Hindus, an arrangement encouraged by nationalists in both religions.

Gandhi was bitterly opposed to the partition. Savarkar was also opposed to it, because he understood that since Hindus were far more numerous in India, they would end up ruling anyway. Gandhi understood this complaint, which is why he was willing to offer the prime ministership of a united India to the Moslem leader Muhammed Ali Jinnah. This attempt met with resistance on all sides: the British, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Jinnah himself, who ended up advocating the two-state plan.

When the partition came, rioting, violence and bloodshed broke out all over India. Gandhi decided to go to centers of the strife in order to try and stop it. He first went to Bengal, where he decided to walk the entire area of the region. He began this ritual every morning at 7:30. (Douglass, p. 55) He was effective. Moslems came forward to protect Hindu minorities and Hindus now returned to their homes.

Gandhi then went to Calcutta and Delhi where the reverse was happening: Hindus were in the majority and they were massacring Moslems. But while Gandhi was doing this, his co-leaders in the India National Congress, Nehru and Sardar Patel, decided to go along with the partition. This allowed them to take the lead in the formation of a post-independence Hindu India. And, in fact, Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India.

Gandhi now wired Jinnah that he was going to Pakistan to show that Hindus and Moslems could live together. The go-between for this last-ditch attempt was a man named Shaheed Suhrawardy, a Moslem whom Gandhi had converted to non-violence.

Around this time, the plot to kill Gandhi now went into overdrive. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte met with an arms dealer named Digambar Badge. (ibid, p. 59) Godse was the editor and Apte the publisher of a newspaper that pushed Savarkar’s ideas. The date they picked for Gandhi’s murder was Jan. 20, 1948. Badge accompanied Godse and Apte on a visit to Savarkar. The mastermind told them, “Return after being successful.” (ibid, p. 70)

This assassination attempt failed because two of the seven conspirators got cold feet at the last minute and failed to start the fusillade after a bomb went off. (ibid, p. 74) One of the plotters, Madanlal Pahwa, was apprehended. He led the police to a room in a hotel where Godse and Apte had held their planning session with others.

In a drawer was a press release from the organization Hindu Mahasabha, a Savarkar-inspired group. Pawha told the police, “They will come again.”

Missed Leads

Pahwa had even talked about the plot to his professor, J. C. Jain, a week before. Jain did not take it seriously until he read about the attempt and Pahwa’s arrest in the papers. He got in contact with the premier and the home minister of Bombay, B. G. Kher and Morarji Desai. He told them the bombing was part of what “appeared to be a big conspiracy.” (ibid, p. 76)

Home Minister Desai, after hearing Jain’s story, said he felt that Savarkar was behind the plot. He then passed on this information to deputy police commissioner J. D. Nagarvala, and ordered him to arrest one of the plotters, Vishnu Karkare, since there was an outstanding warrant on him for another case. Desai also ordered surveillance on Savarkar and shared the information with Sardar Patel, who was in charge of the national government’s security apparatus.

And here begins one of the most puzzling aspects of this case. With all this information being circulated in state, local and national law enforcement circles, how did the plot still succeed?

Douglass tries to point out certain decisions that allowed it to go forward. Patel asked Gandhi to search every person coming to his prayer meetings. Gandhi, of course, refused. Patel then resigned Gandhi “to whatever Providence might have in store.”

Patel was later heavily criticized on this point in the Indian Parliament, because although Gandhi vetoed the searches, he was amenable to other measures. About them he said, “They only believe that this police guard will save my life. Hence let them do whatever they like.” (ibid, p. 78)

Another puzzling point about the interim between the first attempt and the actual assassination is that both the Bombay and Delhi police had information identifying key participants in the conspiracy. (Gandhi was shot in New Delhi.)

Further, both police departments were in touch with each other. Yet, as Douglass writes, “for nine days the assassins moved about freely, until three of them, Apte, Godse, and Karkare then killed Gandhi.” (ibid, pgs. 78-79)

When two officers from Bombay came to brief deputy police commissioner Nagarvala, he told them he had the inquiry under control and ordered them to go back to Delhi. Consequently, the two messengers left only an English note behind. When they returned to Delhi, all they did was write a report about their visit.

What makes this even worse is that by Jan. 25, Pahwa had revealed the names of Godse and Apte. Yet this information was not wired or flown into Bombay. It was sent by person via a train ride of 36 hours. Yet, at this time, both Godse and Apte were actually in Bombay! But by the time the message was delivered on Jan. 27, the two had just left for Delhi by plane. (ibid, p. 80)

But then, why, at the very least, did deputy police commissioner Nagarvala not arrest Savarkar? Or at least detain him for questioning? He replied to this by saying that if he did that before the murder there would have been a huge upheaval in the region. In other words, he made an investigative decision based upon political considerations. (ibid, p. 81) Three days later, in the early evening hours of Jan. 30, 1948, Godse fired three shots, killing Gandhi.

Shielding the Architects

At the trial, Judge Atma Charan blasted the police and security forces for their delay in using the Pahwa confession and Jain information to their greatest advantage. Tushar Gandhi believes that the real reason for this was that many in the police were secret members of either the RSS or Hindu Mahasabha.

But further, the Kapur Commission discovered that there was a blueprint that the police had in their files for these types of situations. Spotters were to be used at local airports and other key Delhi locations like hotels. Plainclothes police should have ringed Gandhi twice: one ring at a range of 25 yards, and the second at three yards away. (ibid, p. 89)

At the trial, Savarkar was not convicted. And it was for the same reason as with the Wyllie murder. Godse and Apte protected him as they were led to the gallows. Although Badge testified that there were meetings between Savarkar and the plotters before the murder, his testimony stood alone.

Yet, as Douglass writes, the government had two more witnesses to these meetings who they did not put on the stand: Savarkar’s bodyguard and secretary. In fact, a month after the murder, Patel wrote to Nehru that “It was a fanatical wing of the Hindu Mahasabha directly under Savarkar that (hatched) the conspiracy and saw it through.” (ibid, p. 93) The Kapur Commission later agreed with this judgment in similar words: “All these facts taken together were destructive of any theory other than the conspiracy to murder (Gandhi) by Savarkar and his group.” (ibid)

Godse was allowed to make a nine-hour speech at the trial explaining the reasoning behind his act. He said it was because Gandhi was submitting Hindus to Moslem blows. And he would have even allowed an invasion of India by Pakistan. Savarkar later said the same, namely that Gandhi wanted a weak conglomerate of India while Savarkar wanted a strong Hindu India. (ibid, p. 95)

With Savarkar’s true role covered up, the RSS became the major party in India. This then created a group of smaller satellite nationalist parties, which are perhaps one of the most powerful political forces in India today. Human Rights Watch has stated that the RSS has plotted to move Moslems out of India and that the party “circulated computerized lists of Moslems homes and business to be targeted by the mobs in advance.”

Without Gandhi, Nehru succumbed to the desire to make India a nuclear power. This, in turn, caused Pakistan to do the same. Gandhi was vigorously opposed to this policy. “Means are not to be distinguished from ends,” Gandhi said. “If violent means are used, there will be bad results.”

He added that if political leaders are truly to be statesmen then they must give up the worship of mammon. This is something Gandhi always believed in. He once said that when he started in South Africa, he had nothing except 3,000 people to support. He was fine. “Then money began to rain from India. I had to stop it for when the money came my miseries began,” he said. “The fact is, the moment financial stability is assured, spiritual bankruptcy is also assured.” (Ibid, p. 110)

Jim Douglass has written a penetrating and valuable book about one of the great statesman of our time. And unlike the Hollywood version, the author informs us that the secrets of Gandhi’s death are almost as important to us as the sterling exemplar of his life.

Jim DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era.

“Author James Douglass , who produced a thoughtful book on President Kennedy’s assassination.”

Thoughtful but not thoughtful enough for the Christian theologian to mention the most obvious scenario presented in The Missing Link in the JFK Assassination Conspiracy by Michael Collins Piper.

http://www.amazon.com/Final-Judgment-Missing-Assassination-Conspiracy/product-reviews/0974548405/ref=cm_cr_pr_btm_link_2?ie=UTF8&filterBy=addFiveStar&pageNumber=2&showViewpoints=0

In the book, Douglass talks about how certain people in the RSS have worked overtime to rehab Savarkar–the guy has an airport named after him–and smear Gandhi. And he portrays this as part of the original cover up.