Giorgio Cafiero says the neighboring North African country’s non-interference stance is informed by Algeria’s own experiences under French colonial rule.

The Libya Summit in Berlin, Jan. 19, 2020. (U.S. State Department, Wikimedia Commons)

By Giorgio Cafiero

Special to Consortium News

Following NATO’s intervention in Libya in 2011, the oil-rich North African country has been bogged down in multiple political crises. Since Libya’s civil war erupted in May 2014 the country has remained bifurcated between two centers of power, one in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk. Since April 2019 — when General Khalifa Haftar’s self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) launched its westward offensive dubbed “Operation to Liberate Tripoli” — Libya’s conflict has been spiraling out of control.

Following NATO’s intervention in Libya in 2011, the oil-rich North African country has been bogged down in multiple political crises. Since Libya’s civil war erupted in May 2014 the country has remained bifurcated between two centers of power, one in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk. Since April 2019 — when General Khalifa Haftar’s self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) launched its westward offensive dubbed “Operation to Liberate Tripoli” — Libya’s conflict has been spiraling out of control.

The many deep interests and conflicting agendas of so many powerful foreign actors unfortunately dim the prospects for diplomatic efforts to successfully wind down Libya’s crisis in the foreseeable future.

This month’s Berlin Conference on Libya was good for, if nothing else, raising global concern about the Libyan crisis and for placing greater focus on the destabilizing impact of foreign interference in the North African country’s internal affairs. But without any means to enforce pledges made by the attending countries with respect to halting arms deliveries to Libyan factions, it is difficult to imagine any concrete and positive change in Libya coming out of Berlin.

Enter Algeria

Hundreds of refugees from Libya line up for food at a transit camp near the Tunisia-Libya border. March 5, 2016. (United Nations)

Algeria, a neighbor and historically influential diplomatic actor in the Maghreb, has been left out of too many analyses on Libya’s post-Qaddafi crisis. Part of the reason has to do with Algeria’s respect for Libyan sovereignty. The leadership in Algiers been has principally and pragmatically opposed to foreign intervention in Libya. The Algerian view on non-interference in the affairs of foreign countries is heavily informed by the North African country’s historical experiences under French colonial rule and popular resistance to it.

With little support from other Arab League members, Algeria stood against NATO/Gulf intervention in Libya amid the “Arab Spring” unrest of 2011. Since August 2014, Algiers has opposed Egypt and the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) intervening in the Libyan civil war. It should be noted that because Egypt shares a border with Libya, Algiers finds Cairo’s intervention to be negative albeit less unreasonable than Abu Dhabi’s role in Algeria’s war-torn neighbor. Also, despite its strong partnership with Moscow, Algeria has opposed the Wagner Group — a Russian military company, which is often described in Western media as President Vladimir Putin’s shadowy mercenary force — helping the LNA amid Haftar’s push to capture Tripoli.

As Algeria’s leadership has stressed, the LNA toppling the Government of National Accord, or GNA, would cross Algiers’ “red line.” This position, however, has not translated into support for Turkish military intervention in Libya, even if Ankara is defending the Tripoli-based administration that Algeria, along with the United Nations, recognizes as Libya’s legitimate government. As is the case in other Arab states, there is concern in Algeria about President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s so-called neo-Ottoman foreign policy, plus Turkey’s NATO membership, which both impact the Algerian government’s positions in relation to Ankara’s military intervention in Libya.

Nonetheless, Algeria has greater problems with Abu Dhabi’s actions in Libya than anything that Turkey is doing in the North African country. With Algeria respecting the GNA’s legitimacy and Abu Dhabi backing Haftar as he attempts to topple that government in Tripoli, Algiers’ perspective on Turkish versus Emirati interference in Libya is understandable. Nonetheless, it is inaccurate to conclude that Algeria has embraced Turkey’s role in Libya, even if Ankara —along with Rome and Doha — would like to see Algiers align more closely with them on the Libya file.

Algeria’s Stakes in Libya’s Future

Rather than arming certain proxies, partners, or clients in Libya, Algeria has embraced a neutral position. Algeria desires the restoration of peace and stability, above all else, in Libya. Similar to Tunisia, Algeria is a neighbor of Libya with grave and extremely valid concerns about the spillover of chaotic violence. The In Amenas hostage crisis of January 2013, carried out by armed Salafist-jihadists — some of whom came from Libya — underscored Algeria’s vulnerabilities to Libya’s chaos. Within this context, Algeria has been spending $500 million on securing its Libyan border and that figure has recently increased following escalation of the conflict with more foreign intervention.

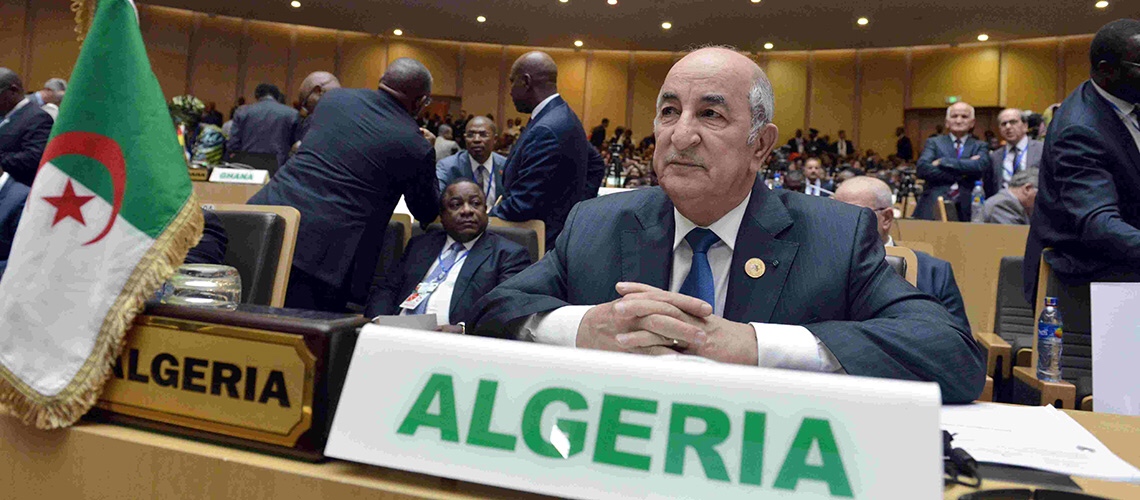

Last year, Algeria was in a weak position to exert its influence in Libya because of Algerian President Abdulaziz Boueflika’s ouster and the transition to a new head-of-state, Abdelmadjid Tebboune.

Algeria’s Abdelmadjid Tebboune in 2017. (SPS RASD/Flickr)

Yet with less internal uncertainty in Algeria this year, Algiers will attempt to play a more pronounced role in terms of facilitating dialogue between Libyan actors themselves, which the Berlin Conference did not feature. This month, Algeria’s government has been working hard to bring actors together to discuss the Libyan crisis in the hope of finding some common ground. On January 23, Chad, Egypt, Mali, Niger, Sudan, and Tunisia’s chief diplomats met in Algiers to discuss plans for resolving Libya’s conflict while Germany’s foreign minister also attended the meeting. The GNA’s top diplomat, however, did not attend the meeting in Algiers because there were rumors that Haftar would be present.

Yet with Turkey, Russia, the UAE, France, and Egypt pursuing their own agendas in Libya, it remains to be seen how much Algeria will be able to rein in these foreign powers’ ambitions. The reality is that Ankara and Moscow are the two main external players shaping events on the ground in Libya and officials in Algiers will have to strategize accordingly, ultimately balancing good relations that Algeria has with both the Turkish and Russian governments in order to gain greater leverage when it comes to advancing Algerian interests in Libya. Nonetheless, that will likely be no easy task for Algiers.

Unquestionably, Algerians and their leaders will continue to have a negative view of foreign interference in Libya. The view is that ultimately neighboring Algeria and Tunisia will pay the price for the further internationalization and dangerous escalation of Libya’s civil war as a result of actions taken by countries that do not border war-torn Libya. The Algerians, who suffered from the “Black Decade” of the 1990s, are all too familiar with violence that terrorizes a population and shatters dreams. In this context, Algeria’s government will seek to play its cards in order to prevent its neighbor from becoming the Arab region’s “next Syria.”

Disturbing from Algeria’s perspective is the likely possibility that the renegade general will never engage the GNA diplomatically as he is ambitiously hellbent on capturing every inch of Libyan territory, even if that requires years of continued warfare. Unquestionably, if the North African country remains bogged down in its nightmarish conflict, Algeria will be forced to pay for sharing a 620-mile border with Libya.

Giorgio Cafiero (@GiorgioCafiero) is CEO of Gulf State Analytics (@GulfStateAnalyt), a Washington-based geopolitical risk consultancy.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

If you value this original article, please donate to Consortium News.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will not be published. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments, which should not be longer than 300 words.

Any viable, long term solution to the present nightmare in Libya will have to respect the sovereignty of the Libyan people by fostering conditions that will allow them to express their political will non-violently. The only practical way to achieve this is for the major global actors and their various regional proxies to step back and allow Libya’s North African neighbors to truly lead the process in concert with the various indigenous Libyan factions.

However, as long as the greater geo-strategic reasons which drove the original destruction of the Gaddafi regime in 2011 remain unresolved, there is little chance that the global players and their proxies will permit any peace in Libya. Unfortunately, these underlying and overriding geo-strategic factors are rarely acknowledged leaving any Libyan political/security analysis either incomplete or wildly inaccurate.

Gaddafi’s plan to use Libyan oil wealth to fund a gold-backed pan African dinar posed a direct threat to not only the U.S. PetroDollar, but also to France’s control of the ten countries forced to use the CFA franc, which would have a profound effect on the French economy, the euro and the USD. The pan African dinar and its attendant monetary union would also empower African countries to demand a greater return for their natural resources and almost certainly hasten the increasing influence of China in Africa, neither of which is acceptable to the U.S. and western economic elites.

Additionally, the overriding need to slow the decline of the U.S. PetroDollar requires limiting global oil production outside of the U.S., especially of those countries inclined to sell their oil in currencies other than the USD. Thus, we see the two invasions of Iraq and its ongoing occupation, the near total destruction of Libya, the massive destabilization of Syria and the extreme sanctions against both Iran and Venezuela.

The escalation of Mediterranean pipeline politics further complicates this intersection of competing global agendas which keeps the Libyan nightmare ongoing.

Unless and until these greater geo-strategic issues are resolved there is little prospect for peace in Libya, this horrifically violent stalemate will continue, and the Algerians will need to further harden their border with Libya.

…and not to forget the USD and French Franc in the CFA vs Gaddafi’s rumblings about Gold Dinars.

Thank you for sharing your analyses on the region. This is not reported very clearly on the news at hand.

The article repeats the claim that the GNA is the legitimate government. how can that be when it was appointed by the UN in Tunisia, was never accepted into Libya and is held only by the support of foreign backed militia mercenaries? The LNA is depicted as a group led by General Khalifa Haftar attempting to topple the legitimate government. The LNA is supported by the great tribes of Libya which represents the Libyan people, General Hafter although not trusted, for whatever reason is being employed by the great tribes. The article perpetuates the western interventionist model of placing legitimacy upon those of it’s own creation, by accepting and propagating such falsehoods .

In as far as any of the “governments” in Libya today can be considered legitimate, it seems to me that it is the government established by the semi-elected parliament currently based in Tobruk. And they have appointed Haftar, so he is hardly a “renegade general”.

Thanks for this update. A review of the origin and sponsors of GNA and Haftar might be illuminating.

Was not GNA a “containerized government” set up by the West ruling from a ship in Tripoli?

Did Haftar not have a USG connection as a rumored resident near Langley in Virginia?

Did not France have a role, seeking gold reserves held by Ghaddafi?

Perhaps links to reference/background articles would help readers catch up on the issues.

…and no mention of Clinton-Obama’s role in destroying a stable country.

> Did Haftar not have a USG connection as a rumored resident near Langley in Virginia?

Indeed, and he is a dual Libyan-US citizen, and was considered to be “the CIA’s man” when he first returned to Libya after the NATO-enforced putsch. I have no idea whether the CIA itself thought so…