Even after honorable discharge, foreign-born veterans who get arrested run the risk of deportation, writes Colonel Ann Wright.

By Ann Wright

Special to Consortium News

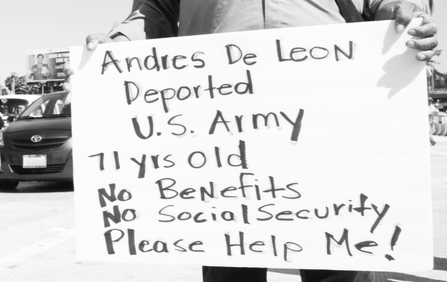

No U.S. military veteran should face deportation, but many do.

No U.S. military veteran should face deportation, but many do.

United Deported Veterans, with an office just off the plaza after crossing the U.S. border into Tijuana, Mexico, helps deported vets find housing, get medical care and access disability checks if they have a disability pension from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

It is also tracking more than 400 non-citizen U.S. veterans with green cards who have been deported for conviction of crimes in the U.S. Most of the crimes are nonviolent, drug-related charges. Many deported veterans have been living in the U.S. for decades.

During a visit to his office earlier this month, Hector Lopez, the group’s office director, estimated thousands more non-citizen U.S. veterans have been deported and have not sought assistance from his office.

Three percent of the U.S. military veteran population in 2012, or about 608,000, were foreign-born. All of these veterans should ensure they have citizenship to protect themselves from deportation.

Recruited on Citizenship Promise

Many deported vets, according United Deported Veterans’ Lopez, were recruited to join the U.S. military on the promise that it would provide a path to citizenship. However, once enlisted, few unit commanders help them file the necessary paperwork or provide time to keep the various appointments required to complete the citizenship package.

Please Make a Donation to Our

Spring Fundraising Drive Today!

Lopez says some immigrant veterans who have lived in the U.S. most of their lives assume they became citizens by virtue of their military service.

That was what he once thought, too.

Gerry Condon, national president of Veterans for Peace; Colleen Smith, Gulf War vet; author Ann Wright; Hector Lopez, deported U.S. veteran; outside United Deported Veterans office, April 2019. (Ann Wright)

Lopez was brought by his parents to the U.S. from Mexico when he was 3 years old. He grew up in Fresno, California, served in the military and was honorably discharged. Remarkably, it wasn’t until he was convicted of a nonviolent crime as a civilian and deported to Mexico, that he realized he was not a U.S. citizen and that being a U.S. veteran did not protect him from deportation.

Many veterans born in Mexico are deported to Tijuana and several have settled there. Veterans for Peace has established a chapter in Tijuana for deported veterans who assist other deported veterans in ways similar to United Deported Veterans; with housing help, access to medical care, getting VA disability checks. Members are also providing food and water for a church near the U.S. border that is housing people from Central America and Haiti who are requesting asylum in the United States.

‘Discharged & Discarded’

A 2016 ACLU report “Discharged Then Discarded” profiles 59 veterans, including the charges that landed them in jail and what happened after their deportation. Seventy three percent indicated they had no immigration attorney representing them in their removal proceedings often because they could not afford to hire one. As a result, many were deported to countries where they were born but have no ties.

Due to their military training, veterans can be recruited by gangs and drug cartels in the countries to which they are deported, the ACLU report notes. Deportation also means breaking up families and losing access to VA medical assistance that many vets need due to high levels of post-traumatic stress caused by combat in U.S. wars and deployments from Vietnam, Gulf War One, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and now Niger.

U.S. military veteran in front of section of U.S.-Mexico border where deported vets have painted their names. (ACLU report)

In less than one decade, Congress greatly expanded grounds for deportation beginning in 1988 when a new category of crimes “aggravated felonies” was created for which immigrants could be deported. Previously, murder, drug and firearms trafficking were the main offenses for which persons were deported.

Now an aggravated felony could mean any of more than 30 types of offenses, including simple battery, theft, filing a false tax return and failing to appear in court and includes conduct that some states classify as misdemeanors or do not criminalize at all.

Getting back to the U.S. after deportation is hard. An alien who was removed because of an “aggravated felony,” has to stay out of the U.S. for 20 years. For lesser charges, the wait may be five or 10 years before it is possible to apply for a waiver. The severity of the grounds for removal affect the likelihood of having a waiver approved.

As recently as 2012, 24,000 noncitizens were in the military, with 5,000 green-card holders enlisting every year. The highest number of enlistments come from the Philippines (22.8 percent), Mexico (9.5 percent), Jamaica (4.7 percent), South Korea (3.1 percent) and the Dominican Republic (2.5 percent).

National Disabled American Veterans Winter Sports Clinic in Snowmass Village, Colorado, 2009. (U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Desiree N. Palacios)

The number of veterans receiving disability benefits has increased dramatically since 2001, reports Lawyers for the Disabled. This is due to injuries, both physical and mental, from the U.S. wars. In 2000, approximately 2.3 million veterans received disability compensation, but 16 years later, after the wars on Afghanistan and Iraq, that number doubled to 4.6 million. Many suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder from what they did or saw in the wars.

Non-citizen U.S. veterans receive lifelong service connected treatment in Veterans Administration facilities located in the United States. However, if a veteran is deported, the only VA facility outside the United States and its territories (Guam, American Samoa, Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands) is in the Philippines.

Most of the deported veterans known to United Deported Veterans are from Central America and do not have the resources to travel to the Philippines for medical assistance.

Among many other remedies, the ACLU, in its report, calls on the Customs and Border Protection to facilitate the parole of deported veterans into the U.S. for medical appointments and family visits.

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a colonel. She was a U.S. diplomat for 16 years and served in U.S. Embassies in Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Micronesia, Afghanistan and Mongolia. She resigned from the U.S. government in March 2003 in opposition to President George W. Bush’s war on Iraq. She is co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”

Please Make a Donation to Our

Spring Fundraising Drive Today!

Basically, the American government exploits illegals to do work that most citizens have no taste for, just like big business. In this case the work is not picking beans or lettuce in the Central Valley or poleaxing steers in Omaha for Cargill, but killing and dying in foreign lands that Uncle Sam wants to add to his collection of puppet states. Those poor souls must feel so exceptional and indispensable… until they are discarded like wads of Charmin that have served their intended purpose.

Well said! Frankly, I don’t understand why ANYONE would VOLUNTEER for U.S. military—especially, NON-citizens who have been DEMONIZED FOR YEARS. Yeah, I get people being poor: but, working for WalMart or McDonalds is about the SME pay as the army & you WON’T get maimed or killed (or have to maim & kill other human beings). We HAVE to find a way to PERSUADE people to NOT ENLIST. In the meantime, STTAND WITH THESE VETERANS.

This is what you get for trusting *anything* americanistan. Chase a dream, find a nightmare.