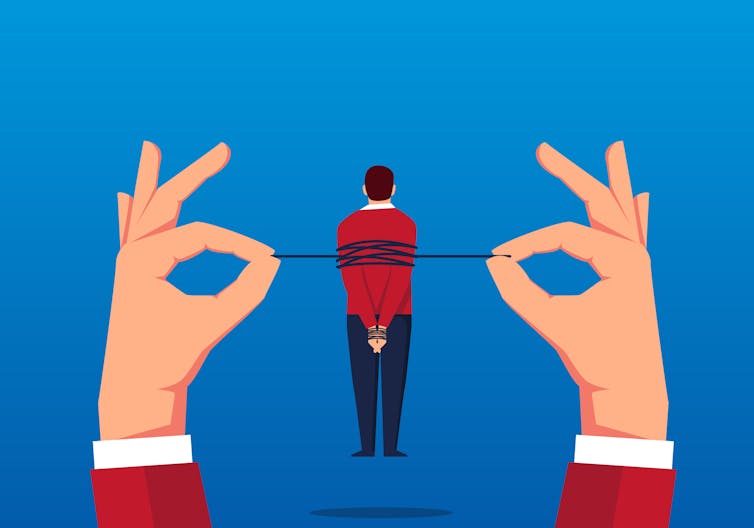

The potential of automation to reduce working hours is inconsistent with the profit motives of capitalist companies, writes Alec Stubbs.

Labor-saving technologies have not afforded workers more leisure time. (Pict Rider/iStock via Getty Images)

First it was the “Great Resignation.” Then it was “nobody wants to work anymore.” Now it’s “quiet quitting.”

First it was the “Great Resignation.” Then it was “nobody wants to work anymore.” Now it’s “quiet quitting.”

Yet it seems like no one wants to talk about what I see as the root cause of America’s economic malaise – work under contemporary capitalism is fundamentally flawed.

As a political philosopher studying the effects of contemporary capitalism on the future of work, I believe that the inability to dictate and meaningfully control one’s own working life is the problem.

Democratizing work is the solution.

The Problem of Work

What can be said about the malaise surrounding work under capitalism today?

There are at least four major problems:

First, work can be alienating. Workers are often not in control of how they work, when they work, what is done with the goods and services they produce, and what is done with the profits made from their work.

This is particularly evident in the rise of precarious forms of work, like those that are found in the gig economy.

According to the Pew Research Center, there’s been a decline in people finding meaning in their work. Nearly half of front-line managers and employees do not think that they can “live their purpose” through their jobs.

Second, workers are not paid the full value of their labor. Real wages have not kept pace with productivity, driving economic inequality and a decline in labor’s share of income.

Third, people are time poor. In the U.S., full-time employed workers work an average of 8.72 hours per day despite productivity increases. Long working hours, along with a number of other factors, contribute to the feeling of “time poverty,” which has a negative impact on psychological well-being.

Constrained by the demands of work, many people find they have little time to pursue their own interests. (z_wei/iStock via Getty Images)

Fourth, automation puts jobs and wages at risk. While technological innovation could in theory liberate people from the 40-hour workweek, as long as changes aren’t made to the structure of work, automation will simply continue to exert downward pressure on wages and contribute to increases in precarious employment.

Ultimately, the potential of automation to reduce working hours is inconsistent with the profit motives of capitalist companies.

Humanize Work or Reduce It?

On the one hand, many people lack work that is personally meaningful. On the other hand, many are also desperate for a more complete life — one that allows for creative self-expression and community-building outside of work.

So, what is to be done with the problem of work?

There are two competing visions of the best way to arrive at a solution.

The first is what Kathi Weeks, author of The Problem with Work, calls the “socialist humanist” position. According to socialist humanists, work “is understood as an individual creative capacity, a human essence, from which we are now estranged and to which we should be restored.”

In other words, jobs often make workers feel less human. The way to remedy this problem is by re-imagining work so that it is self-determined and people are better compensated for the work they do.

The second is what’s known as the “post-work” position. The post-work theorists believe that while doing some work might be necessary, the work ethic, as a prerequisite for social value, can be corrosive to humanity; they argue that meaning, purpose and social value are not necessarily found in work but instead reside in the communities and relationships built and sustained outside of the workplace.

So people should be liberated from the requirement of work in order to have the free time to do as they please, and embrace what French-Austrian philosopher André Gorz called “life as an end in itself.”

While both positions might stem from theoretical disagreements, is it possible to have the best of both worlds? Can work be humanized and play a less central role in our lives?

Democratic Worker Control

My own research has focused on what I see as a critical answer to the above question: democratic worker control.

Democratic worker control – where companies are owned and controlled by the workers themselves – is not a new concept. Worker cooperatives are already found in many sectors throughout the U.S. and elsewhere around the globe.

In contrast to how work is currently organized under capitalism, democratic worker control humanizes work by allowing workers to determine their own working conditions, to own the full value of their labor, to dictate the structure and nature of their jobs and, crucially, to determine their own working hours.

This perspective recognizes that the problems people face in their working lives are not merely the result of an unjust distribution of resources. Rather, they result from power differentials in the workplace. Being told what to do, when to do it and how much you will earn is an alienating experience that leads to depression, precarity and economic inequality.

Being told what to do and when to do it can make you feel helpless and dispirited. (rudall30/iStock via Getty Images)

On the other hand, having a democratic say over your working life means the ability to make work less alienating. If people have democratic control over the work they do, they are unlikely to choose work that feels meaningless. They can also find their niche and figure out what’s fulfilling to them within a community of equals.

Democratizing work also leads to an increase in labor’s share of income and a reduction in economic inequality. It has been shown that unionized workers earn an average of 11.2 percent more in wages than nonunionized workers in similar industries. Income inequality is also much lower in worker cooperatives compared with capitalist companies.

But work should not be confused with the whole of life. Nor should it be assumed that a sense of purpose, a sense of belonging and the acquisition of new skills can’t occur outside of work. Playing, volunteering and worshipping can all do the same.

However, in capitalist companies, labor-saving technologies do not afford workers with more leisure time. Instead, labor-saving technologies mean workers are more likely to face unemployment and downward pressure on wages.

Under democratic worker control, workers can choose to prioritize values that are consistent with themselves rather than the dictates of profit-seeking shareholders. Labor-saving technologies make it more likely that leisure time can become a choice. Workers are free to assert their own values, including that of less work and more play.

A Mosaic Approach

Of course, democratic worker control is not a silver bullet to economic discontent, and these changes to the workplace can’t occur in a vacuum.

For instance, trials of a four-day workweek without a reduction in pay are increasingly popular, and they have had resounding success in both the United Kingdom and Iceland. Workers report feeling less stressed and less burned out. They have a better work-life balance and report being just as productive, if not more so.

Federal legislation to reduce working hours without a reduction in pay, such as through the implementation of a four-day workweek, could accompany a movement for democratic worker control.

The expansion of social services, the development of a public banking system and the provision of a universal basic income may also be important components of meaningful change.

A broader movement to democratize the U.S. economy is needed if society is going to take the challenges of work in the 21st century seriously. In short, I believe a mosaic of approaches is necessary.

But one thing is clear: As long as work remains the dictates of shareholders rather than the workers themselves, much work will remain a source of alienation and will persist as an organizing feature of American life.![]()

Alec Stubbs is a postdoctoral fellow of philosophy at UMass Boston.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

I think you need to really study socialist companies by actually taking trips there and do comparisons to our capitalistic ones.

I’ve been to a few during my consultant days around the world and they were learning experiences. If it were not for our capitalist telephony company, their socialist telephony communication systems would still be down. You have some people who are a sleep on the job, and they can’t do what is expected of them in the positions they hold. After we get their tech up, and arrange training days and times for them, most would not show up or care to ask questions or take notes.

It is a given our capitalistic system is flawed, but I would have to say other economic systems are also problematic.

Maybe if we have some type of hybrid system this might be better, but I doubt it. Why? People are flawed and they can easily be not motivated to work if you give them $ and not properly manage them. Look at our own Fed, state, and cities employment systems. You will see plenty of problems there. That is system that needs reforms and constant reminders their customers are the taxpayers.

The years of taxpayer debt didn’t happen overnight: hxxps://www.usdebtclock.org/

If workers want to dictate and meaningfully control their own working life then they need to come up with their own capital, instead of using someone else’s.

More like they need to take control of the capital already in existence which they have created through their time and labor, which has been systematically stolen from them by anglers and grifters. What, of any value, is actually created by the “financial services industry”, banking, or insurance? These are rackets, if well-institutionalized ones.

Anglers and grifters that are fully in control of the political system and are not giving up that control. If workers want to succeed in breaking away from their current situation then they need to create their own institutions and build from the ground up.

I agree a hundred-fold…I was just pointing out that there is as much taking-back-of-what-is-already-there as well as building-from-the-ground-up that needs to happen.

I believe that trying to take back what is already there is a can of worms best left unopened. Who can be relied on to decide what shall be taken back and from whom? Workers should just organize themselves and go forward.

Interesting points. My biggest concern is the automation will decrease employment, which will in turn decrease markets, which, together, are a formula for economic collapse. The answer is a reduced work week and guaranteed minimum income, in the manner proposed by Richard Nixon in 1972, perhaps one of the real reasons he was forced from office.

The point of work in the USA so far is to work harder and harder for less and less wages for people who have never had it better. And to support the building and selling of weapons of war so we can kill those who demand independence from US hegemony.

This is a very, very good departure from standard takes on the subject. We can see what the billionaire oligarchy can do with the economy. In this atmosphere Winston Smith lackeys’ll shoot down anything with the word “socialism” in it. So Stubbs’ approach makes sense, and perhaps it could be sufficient to yield something (that in itself would be an unanticipated revolution; while media is making people dumber, one portion of it is enabling a beginning of a widespread understanding and analysis?). But I have two problems with it. Capitalism didn’t start with the dark satanic mills of the 18th century; it’s been an enduring hassle over millennia. The second one is that all approaches that are close to this one by Stubbs (and Stubbs’ itself somewhat) focus on pieces of the picture. So while halfway grasping globalization…(as shortsighted as it is) analyzers take for granted that a country can adjust elements of “work” even if it’s shot itself in the foot vis a vis its global standing (sanctions). No, it can’t. So a real analysis of the problem has to deal also with partially weaning the world off globalization, which entails finding solutions to geopolitical problems at the same time [you can’t peacefully go to “partial,” or even retain the portion of it you had prior without such solutions].

Where Stubbs is right with his approach is the focus on lack of meaning and automation. The first is the bigger problem. One breadwinner in a family working at a steel plant in PA, and putting a couple kinds through college…is a classic measuring stick [I’ll bracket aside for now “problems” on the job associated with that]. There was a product in view…to work toward, which gave meaning. Today not all jobs in what Michael Hudson calls the “real economy” are filled by “essential workers.” To overwork workers in some jobs in the real economy might make twisted capitalist sense [no benefits and they can be easily replaced]. With the billionaire ethos, though, a pet theory gets way too much emphasis. They have so much power they can beat everyone over the head with it [shades of Herman Daly?]. There may be little to no meaning in retail, but when you apply the “easy replacement” theory [of the billionaires and private equity] to “essential” healthcare workers, then these workers crazily get a taste of, say, retail job uncertainty. Of course, the former had more meaning in their work, and it took time to train’em. It’s bad enough the lowest level essential workers find no meaning in their work, but if even the next level up has to experience backbiting and paranoia…due to everyone’s fear of losing their slot [I guess especially when it’s doing meaningless things]…then these workers are truly somebody’s rats in somebody’s maze. I get the feeling the extremeness of this situation is not fully understand by all those parents whose kids CAN NOT handle moving out. Or by all the people in our intelligentsia who offer their solutions. And I get the feeling, if they understood it, they wouldn’t be so quick to write off the solution I’m gonna float below.

A partial answer I believe is a whole change of zeitgeist. For a time you just couldn’t shoot yourself down in terms of globalization (to the extent we participated in it at all in the recent past). And, since we don’t manufacture that much, a specialization like Cuba’s to me would make sense…medical [not making F-35s]. Recently I heard someone on Sputnik suggest we plop down a state of the art chip making plant in Detroit. I don’t imagine it’s that easy. Aside from the bigger problems, even if amidst a tangle of sanctions you could find reliable buyers/users…and even if these buyers were making something local…you still would have the problem of people not having enough dough to buy what they were making. And the reason for that is the stubborn fact that long ago you offshored that PA job to elsewhere (plus the tangled enduring SWIFT system which’ll end up phased out, leaving the west with what, or on what end of things??). Realize/admit the karma, and change the zeitgeist. Do exactly what that little nation to the south did we maligned so much. Of course we need a new New Deal, but giant earth moving projects and building dams aren’t that environmentally feasible given what we’ve got left of the biosphere.

see “Sick Profit: Investigating Private Equity’s Stealthy Takeover of Health Care Across Cities and Specialties”

sorry…putting a couple kids through college, not kinds

Maybe society needs to have a serious and honest discussion about ‘what is the point of work ?’

Most important is wage/economic equality.

Owners — not investors and speculators and vultures — must determine what is produced, and then pay fair wages to workers while keeping a fair amount for themselves.

¡Slavery is not okay!

Yes, and the point of money too. Ideas about it float around half baked. “full faith and credit”…what if it ends up the world has no faith in our money? After all, they wanted the globalization and now it’s here. There are some strange ideas that we can just print it up. Sure money under our system is elastic [I wouldn’t advocate going back to the gold standard, nor say a central bank’s ability to print a little extra at given times isn’t a good thing], but what does production produce here that a majority of the world wants? If I could make earrings out of unique shells that people really wanted, then perhaps the shells they were made from could serve as money. Or later you could fashion verifiable symbols of the shells; but, if you made too many more symbols than everyone realized there were shells, or more than everyone realized there was demand for such earrings, wouldn’t faith start to ebb? When you get to the rock bottom of the matter, Henry, [not saying eventually countries couldn’t be more self sufficient] if SWIFT met its match and no one wanted our treasuries [nor any of our oft bomb-prone “financial vehicles”], then I think at that time most likely we’d have to think about what our country produces with its work.