Allegations about efforts within the U.K. establishment to bring down Britain’s Labour government in the 1960s and 70s have resurfaced with a file released on Tuesday by the National Archives, Richard Norton-Taylor reports.

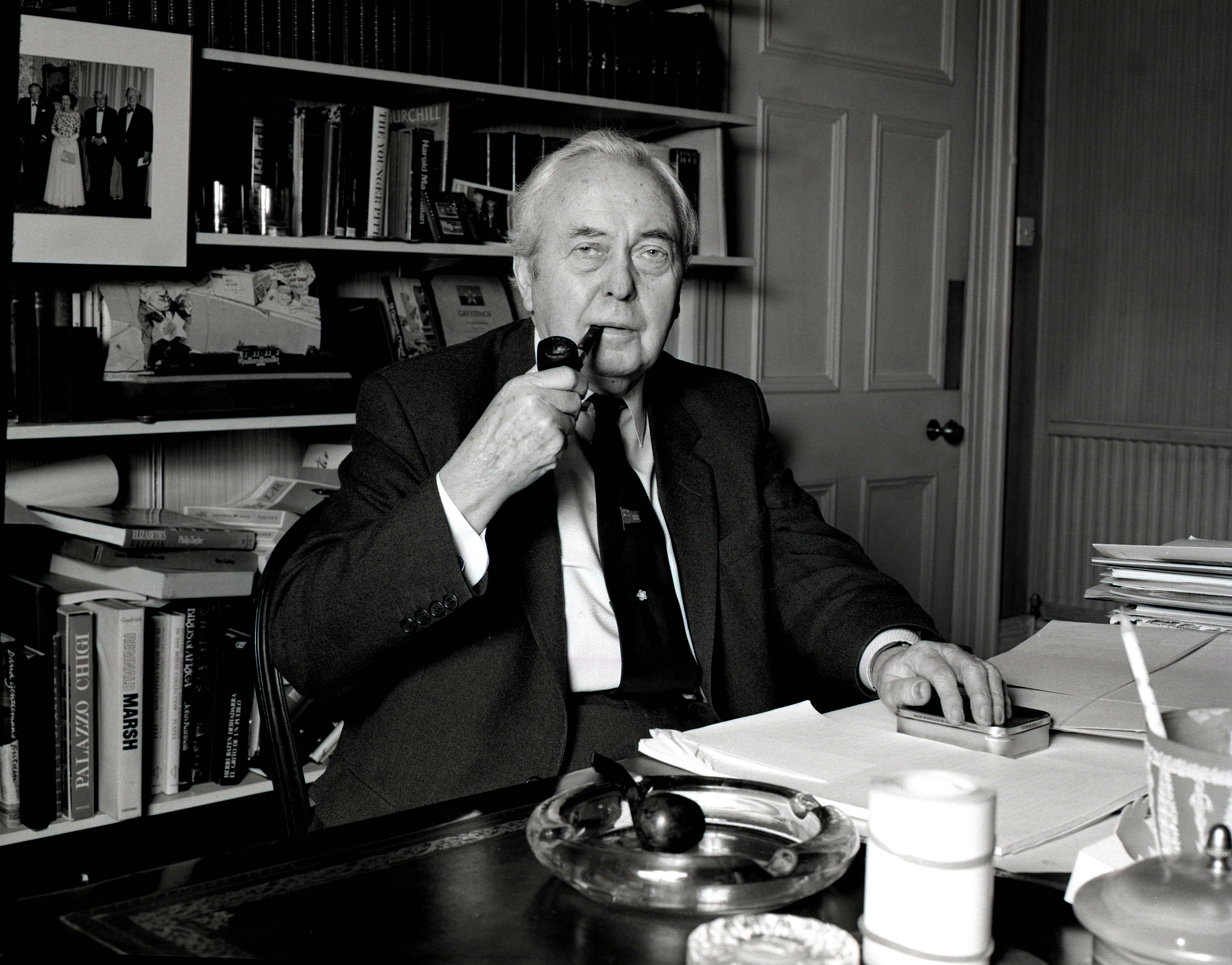

Former Prime Minister Harold Wilson in 1986. (Allan Warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

By Richard Norton-Taylor

Declassified UK

A file released on Tuesday by the U.K. National Archives, titled “Allegations concerning a possible coup in 1968,” reveals how rattled MI5 and the Home Office were many years later about conspiracies that have never been properly investigated.

A file released on Tuesday by the U.K. National Archives, titled “Allegations concerning a possible coup in 1968,” reveals how rattled MI5 and the Home Office were many years later about conspiracies that have never been properly investigated.

The declassified file refers to discussions about how to topple the then Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson.

Wilson was smeared by right-wing groups aided by sections of the media suggesting that he was a security risk because some of his acquaintances had had links with former KGB officers.

The document contains a “background note” written by a Home Office official in 1981 referring to “recent revelations” that “a possible ‘coup’ was discussed between Lord Mountbatten, Mr. Cecil King and Lord Zuckerman in May 1968.”

Mountbatten was a former chief of the defence staff and the queen’s cousin; Cecil King was chair of the International Publishing Corporation (IPC), which owned the Daily Mirror newspaper; and Solly Zuckerman was the government’s former chief scientific adviser.

In an attempt to brush off the revelations’ significance, the Home Office official noted at the time that they were “not new.”

The file also contains a carefully-drafted response to a letter Ted Leadbetter, a Labour MP, had written to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, in April 1981 following newspaper reports referring to plots to get rid of Wilson.

The response to Leadbetter, approved by the head of MI5, Sir John Jones, and Sir Brian Cubbon, the top official at the Home Office, stated:

“There is nothing to suggest anything that came even remotely near to being a serious conspiracy to undermine or overthrow Parliamentary democracy.”

However, the file has been heavily redacted by Whitehall “weeders” and withheld, either in whole or in part, by the notorious section 3(4) of the Public Records Act that allows government departments and agencies to keep official papers secret without having to give any reason.

‘State of the Country’

Lord Mountbatten in 1973. (Allan Warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Tuesday’s file contains a Times newspaper report, dated 3 April 1981, revealing an unpublished entry in Cecil King’s private diary, under the headline, “Mountbatten and the coup that wasn’t quite.”

King had recorded in the entry for 8 May 1968 that he saw Lord Mountbatten “at his request.” King was accompanied by Hugh (later Lord) Cudlipp, the editorial director of the Mirror Group.

Mountbatten had asked Lord Zuckerman, described by Mountbatten as “a man of invincible integrity,” to be present at the meeting. In what Zuckerman later described as “rank treachery,” Cecil King said the queen was said to be worried about the state of the country, the low morale of the armed forces and the prospect of “bloodshed on the streets.”

In his private diary, Mountbatten dismissed King’s ramblings as “dangerous nonsense.”

A few days later, King signed an article across the Mirror’s front page in a devastating attack on Wilson under the banner headline: “Enough is Enough.”

The newly-released file includes a handwritten letter King wrote in October 1981 to the cabinet secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong. In it he refers to newspaper accusations that he had planned a coup, “military perhaps,” to overthrow the government.

King insisted they had “no foundation in fact,” despite the concerns expressed by Zuckerman and Mountbatten and, later, by Wilson himself.

In his letter to Armstrong, King referred to his sudden sacking from the IPC board following his front-page article attacking Wilson. “It now occurs to me,” King wrote, “that Wilson was so disturbed that the Daily Mirror ‘had cooled towards him’ that he ‘decided to remove me.’”

King continued that perhaps Wilson had told his colleagues he had evidence that King was planning a coup. King told Armstrong: “My coolness was due to the fact that Wilson was no prime minister, that he would lose the 1970 election.”

A recent book claimed the queen had to talk Mountbatten out of leading the plot to overthrow Wilson.

Secrecy

In the preface to his official history of MI5 published in 2009 the historian Christopher Andrew referred to redactions he was asked to make. “The most difficult part of the clearance process has concerned the requirements of other government departments,” he wrote.

He added:

“One significant excision as a result of these requirements in Chapter E4 is, I believe, hard to justify. This and other issues relating to the level of secrecy about past intelligence operations … would, in my view, merit consideration by the Intelligence and Security Committee.”

Chapter E4 is titled “The ‘Wilson Plot.” The Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) is a Parliamentary body that has legal powers to scrutinise MI5.

I asked Sir Malcolm Rifkind, former defence and foreign secretary and then chair of the ISC, whether he would take up Andrew’s invitation. He declined.

I made a Freedom of Information Act request to the Cabinet Office asking them to tell me what Andrew was referring to. It refused, saying “Intelligence” material was exempted under the Act.

MI5 ‘Will Have to Consider’

The episode was not the only plot to subvert the Labour leader. Prompted by claims that Wilson’s network included individuals with past links to the KGB, MI5 had been building up a file on Wilson, under the pseudonym “Henry Worthington,” that was kept in a safe in the office of the agency’s director general.

In the 1970s, after Wilson was elected prime minister for a second term, George Kennedy Young, a former vice chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, set up what he called a “Unison Committee for Action” with, among others, the retired general, Sir Walter Walker.

Although this was initially directed at Edward Heath, the Tory leader they regarded as far too soft on trade union leaders, Wilson was its main target.

Former head of MI6, Sir Maurice Oldfield. (Wikimedia Commons)

A steady stream of media reports, combined with talk in Westminster and Whitehall talk about MI5 and other plots to destabilise him led Wilson in 1975 to summon the head of MI6, Maurice Oldfield, and ask whether he knew about them. Oldfield said he did.

“There was a section of MI5 that was unreliable,” journalist David Leigh wrote in his book, The Wilson Plot.

Leigh says that following Wilson’s decision to resign in 1976 for a mixture of personal and medical reasons — his formidable memory was going in what seemed to be the onset of alzheimer’s — Michael Hanley, then head of MI5, was asked what the implication would be if the left winger, Michael Foot, took over as Labour leader.

Hanley replied: “I and every other officer in the service will have to consider our position.”

Stopping Corbyn

Many years later, another elected Labour leader came under attack by a senior member of the Intelligence establishment, this time in the open.

Sir Richard Dearlove, head of MI6 at the time of the invasion of Iraq, intervened at the height of the 2019 general election campaign to deliver a blistering attack on Jeremy Corbyn.

“For what conceivable reason should voters now risk giving Corbyn actual control of our national security policy by electing him to prime ministerial office?” he told readers of the Mail on Sunday.

Corbyn has told Declassified about attacks on him by elements in the British establishment. He gave as an example the Sunday Times quoting a “senior serving general” who warned that the armed forces would take “direct action” to stop a Corbyn government.

The anonymous general added: “There would be mass resignations at all levels and you would face the very real prospect of an event which would effectively be a mutiny.”

When Declassified asked the Ministry of Defence if it had looked into the general’s threat, the department said it held no records of any investigation.

In his official history, Andrew points to Wilson’s successor, James Callaghan’s reference to Wilson’s “paranoia.” If this is what he suffered from, it was understandable. As Joseph Heller observed in Catch 22, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.”

Richard Norton-Taylor is a British editor, journalist and playwright, and the doyen of British national security reporting. He wrote for The Guardian on defence and security matters and was the newspaper’s security editor for three decades.

This article is from Declassified UK.

I was quite young in the 60s but I did follow the information that became public.

Wilson was running the first Labour govt since 1951. He won the election of 1964 by just a few seats. The financial situation was poor. The pound was over valued but the City of London insisted that the parity of $2.80 to the pound be maintained (this was the era of Bretton woods with fixed exchange rates) Devaluation would have affected the Commonwealth countries which held reserves in Sterling and there was pressure from them to maintain the parity. The only way to do that was by deflation and cuts to expenditure. Defence was taking 7% of GDP but the threat of war in Europe seemed much more remote. Russian leaders came to London. And -see picture-Wilson visited Moscow. The Labour govt. took the decision to lower defence spending and end the ‘East of Suez’ role. Social spending was also cut disappointing many Labour supporters.

The Vietnam war was in full swing and President Johnson pressured the Uk for a contribution. It is reputed that he said, ‘even a company of bagpipers’ would be enough!

Involvement in the Korean war at the end of the post war Labour govt. has ruined some of their plans for more social spending. Wilson was not going to go to war.

He called an election in 1966 and won a substantial majority but the economic pressures continued and he de-valued in 1967 to $2.40. In the conservative thinking of the day, de-valuation was a failure, rather than a rational response.

The deflationary measures meant that the govt. opposed a number of strikes calling for higher pay. By 1970 the govt had its first surplus budget since 1947.

The reactionary forces saw most of this in negative terms-the reduction in defence, de-valuation of the pound, not helping the US. Much of the remaining Empire had already been scheduled for independence and was generally accepted by most people but for some it was a sign of national decline. Britain was no longer a world power and Labour became the target of their resentment. A number were really angry and it took a time to get used to the idea.

From my reading since, there was no chance of even the Establishment (with some exceptions) supporting a coup. However, there is also no doubt that a significant rump of people with high connections think they represent the real soul of the nation. These are the very Conservative. There is another group which think only they understand economics and have the right to direct the economy. They also overlap as can be seen in the film ‘The Spider’s Web’ about the network of tax havens. Worth watching.