Rob Lemkin and Femi Nylander say the killing of two protesters last month in Téra, Niger, should turn a spotlight on not only France, but all former colonial powers.

The Rue du Nigéria in Niamey, capital of Niger, 2018. (NigerTZai, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Rob Lemkin and Femi Nylander

Africa is a Country

On the night of Nov. 26, a French military convoy of around 100 vehicles stopped at the Nigérien town of Téra 30 km from the border with Burkina Faso. The convoy, La Voie Sacrée (the Sacred Way), was transporting weapons and equipment from Ivory Coast to Mali as part of France’s counterinsurgency operation against Islamic State jihadists. It had already faced angry protesters in Burkina Faso but nothing quite like what it was to meet the next morning in Téra.

By 11 a.m. the convoy was surrounded by around 1,000 Nigériens, throwing stones and wooden sticks, shouting “Down with France!” According to eyewitnesses interviewed by the French newspaper Libération, a French Mirage-2000 jet dropped tear gas grenades. “After that,” said Faisal Hamadou “the soldiers gathered and opened fire. They fired in front of them, not above, nor to left or right. It was not a single soldier who fired, several of them opened fire.” The French commander, Captain François Xavier, told Radio France Internationale (RFI) his men used non-lethal weapons. He said rifles were only used for warning shots.

Map of West Africa regions by Peter Fitzgerald. (CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Two protesters were shot dead. A third later died in hospital in the capital Niamey. Thirteen others were wounded, and some are still in a critical condition. The Nigérien Interior Minister confirmed the casualties but declined to say whether the lethal shots were fired by French soldiers or the Nigérien gendarmes accompanying them.

TV5 Monde interviewed eyewitnesses and a brother of one of the dead, who maintains the French soldiers did the firing. Videos circulating on social media record a Nigérien gendarme shouting at the French soldiers to stop shooting. French media, however, has so far chosen to highlight images of five Nigériens striking one of the convoy’s trucks with wooden sticks.

Echoes in Colonial Bloodshed

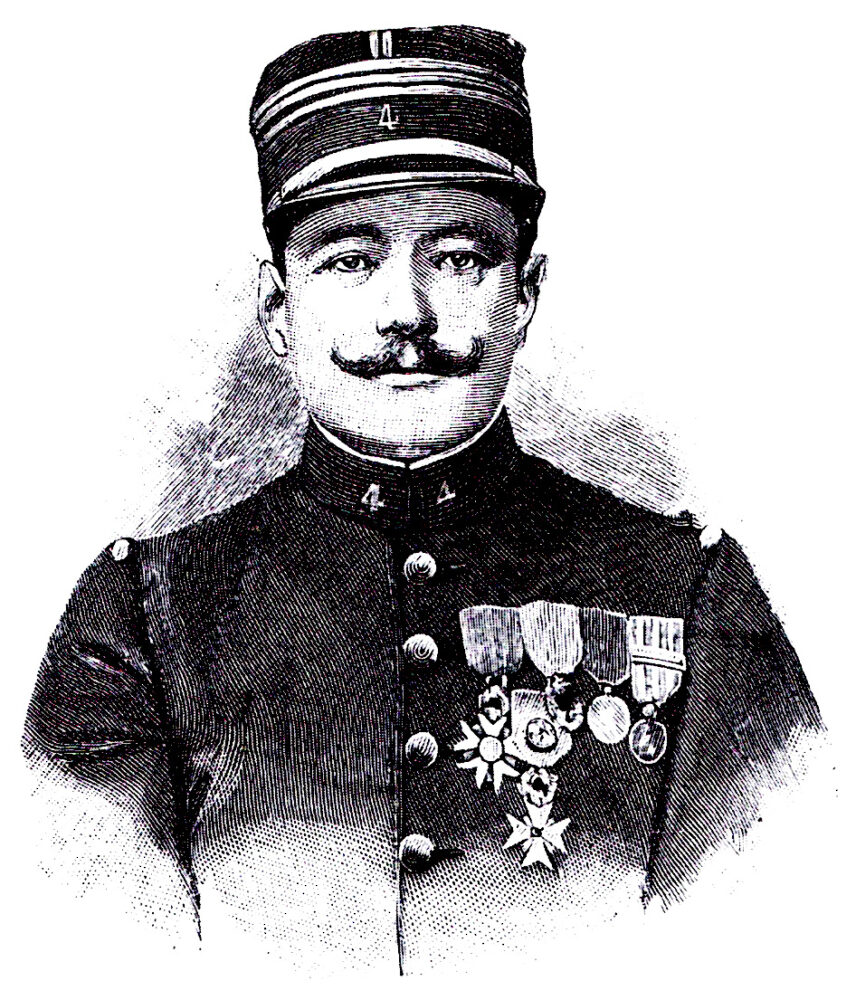

Captain Paul Voulet, from cover of L’Illustration, Aug. 26, 1899. (Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons)

When we filmed our BBC2 Arena documentary African Apocalypse (now serialized on BBC Global), we were refused permission to travel to Téra. It was far too dangerous, the authorities told us. We were tracing the historic route of the French column led by the notoriously brutal turn-of-the-century commander, Captain Paul Voulet that left tens of thousands of Nigériens dead.

One-hundred-and-twenty years later the memories of those massacres that created the colony (and the country’s current borders) are seared into the consciousness of all those we met, old and young alike. Voulet’s violence is still vivid because it marked the start of people’s deplorable present in the world’s poorest country.

We can only presume that the people of Téra today feel the same. They live at the epicentre of an 8-year conflict between Islamic State-affiliated jihadists and the French and Nigérien military. More than 500 civilians have been killed this year alone. Populations in more than 100 villages have been displaced to make way for a French military base in nearby Ouallam. In October, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) warned that nearly 600,000 people there are exposed to food insecurity in a “major crisis.”

Téra is a significant location in the history of Niger and Burkina Faso, for it was here in 1983 that President Seyni Kountché (Niger) and President Thomas Sankara (Burkina Faso) committed their countries to the principles of non-alignment under the Téra Declaration.

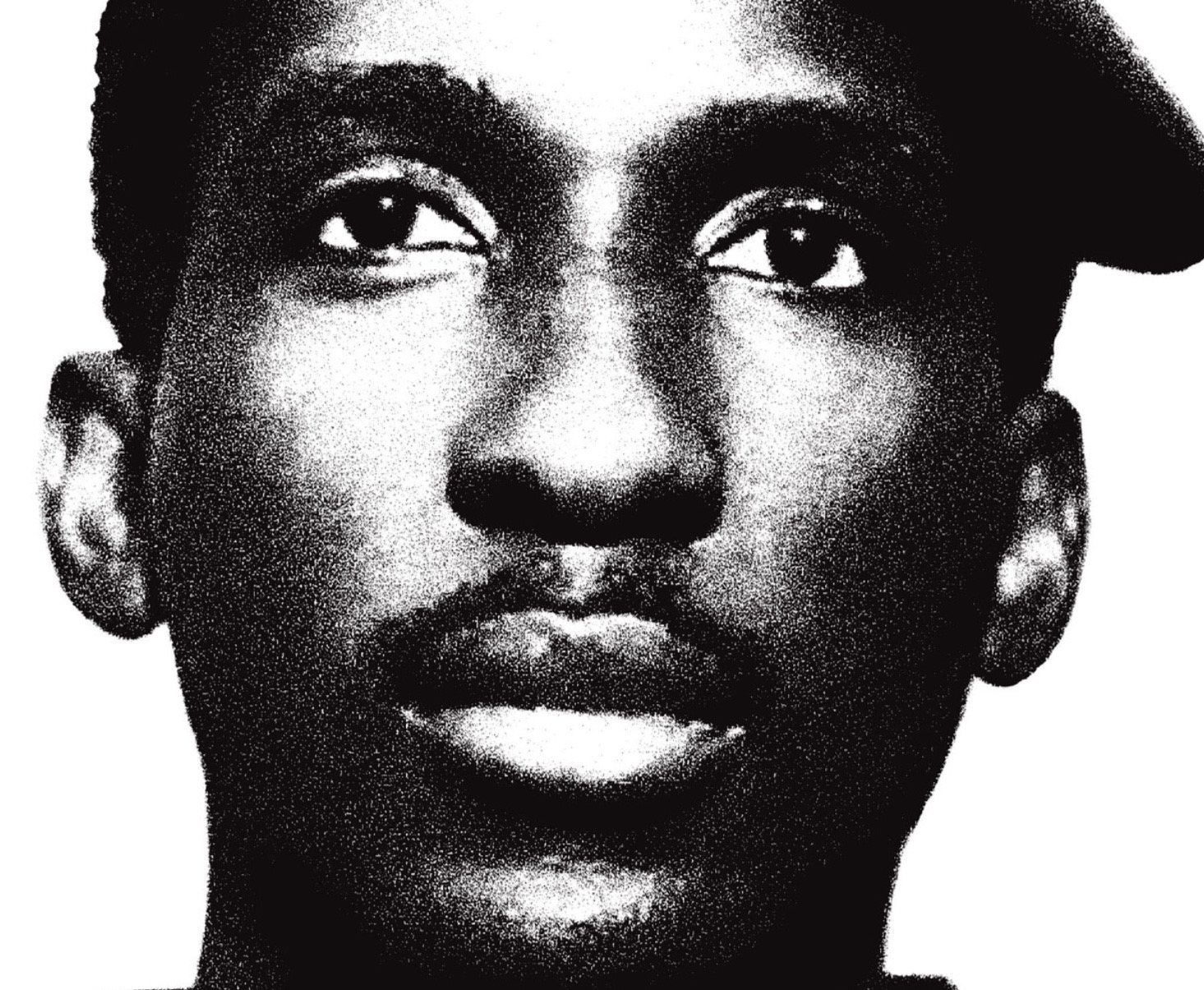

Sankara remains an icon across Africa. His short-lived radical government made the sort of leaps in land redistribution and mass social welfare that today’s protesters in Téra could only dream of. His policies and rhetoric made him a threat to the Françafrique, a network of business and political connections that have kept Paris one of the foremost powers in Africa since independence. He was murdered in a military coup in 1987 that many suspect was carried out with the support of the C.I.A. and French intelligence.

Portrait of Burkina Faso revolutionary, Thomas Sankara. (CCO, Wikimedia Commons)

In October, a trial of 14 men accused of his killing opened in the Burkina Faso capital, Ouagadougou. French president Emmanuel Macron promised in 2017 to release all classified documents on the case. So far three batches have been opened, but none from the office of François Mitterrand, the French president at the time of Sankara’s murder.

The opening of the archives on the 1899 Voulet invasion is also among calls by the Nigérien communities we worked with for our film. In submissions made to the United Nations special rapporteur for the promotion of truth and justice they demand a full investigation, a series of memorials and reparations. But first they ask for an acknowledgement from France and an apology to Nigériens for the 1899 decimation that ushered in its colonial rule.

In the wake of the deaths at Téra, the Nigérien authorities refused permission for a demonstration organized by local NGO Tournons La Page-Niger. On Dec. 11, five activists with the NGO were arrested and charged with involvement in an unauthorized assembly to mark International Human Rights Day.

Earlier, Nigérien President Mohammed Bazoum defended the French presence in the Sahel, saying its departure would lead to “chaos.” The Interior Ministry has opened an investigation “to determine the exact circumstances of the tragedy at Téra and locate responsibilities.” Niger’s Human Rights Commission is also investigating. Let us hope the French military cooperates fully and openly with both inquiries.

Perhaps it can be a new step on the road toward a meaningful Truth and Reconciliation for colonialism in Africa—not just by France, but all the former colonial powers.

Rob Lemkin and Femi Nylander, made the BBC Arena documentary “African Apocalypse” on the French colonial invasion of Niger. It continues on BBC Global until Dec. 20.

This article is from Africa is a Country and is republished under a creative commons license.

Help Us Cover the Assange Case!

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!

Donate securely with PayPal

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button: