British loyalists needed money, homes and acceptance, writes G. Patrick O’Brien.

Detail of Benjamin West’s allegorical painting of the British Empire taking in American loyalists in 1783. (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

By G. Patrick O’Brien

Kennesaw State University

The U.S. has long been a destination for people fleeing war-torn regions of the world. But in 1783, the tables were turned: Between 60,000 and 100,000 disaffected colonists from diverse backgrounds were fleeing the American states newly independent from Britain.

The U.S. has long been a destination for people fleeing war-torn regions of the world. But in 1783, the tables were turned: Between 60,000 and 100,000 disaffected colonists from diverse backgrounds were fleeing the American states newly independent from Britain.

The leaders of these exiles referred to themselves as “loyalists,” a title they chose to underscore the debt they believed the British Empire owed them. The largest group of refugees, around 32,000 people, went elsewhere in North America, to British-controlled Nova Scotia and the newly created British colony of New Brunswick. They had hopes of building a colonial society that would compete with the nascent United States.

By the end of the 18th century, however, many became disillusioned with Britain’s promises to aid its loyal refugees. Some even found repatriation to the United States preferable to eking out life in the empire. Examining the experience of the American loyalists reveals important lessons to consider as the United States prepares to welcome Afghan refugees.

In Need of Money

Perhaps most importantly, like the modern Afghan refugees, thousands of loyalists were desperate for financial assistance.

Describing the pitiful scene of refugees lining up for provisions in Halifax during the summer of 1784, one young woman wrote in her diary, “If I look round me, what thousands may I see more wretched than myself.”

The most destitute refugees, the roughly 3,000 formerly enslaved people who evacuated the Colonies with British forces, needed the most help. But the colonial British government gave these free Black refugees swampy land unsuited for farming. Extreme poverty forced many Black refugees, especially refugee women and children, to work in homes of white loyalists, where they faced the threat of reenslavement, either in Nova Scotia, where slavery remained legal through the early 19th century, or possibly through transportation to the Caribbean.

White refugees and working British Nova Scotians blamed the free Black population for depressed wages. From late July through August 1784, disbanded British soldiers and white refugees attacked the free Black population of Shelburne. They not only inflicted physical violence on Black workers, but they also looted their homes before burning dozens to the ground. The violence drove the free Black population from Shelburne, but it did little to create long-term economic opportunities for white Nova Scotians. At its peak in 1784, Shelburne was one of the largest settlements in British North America. By the early 19th century, most of its homes sat deserted.

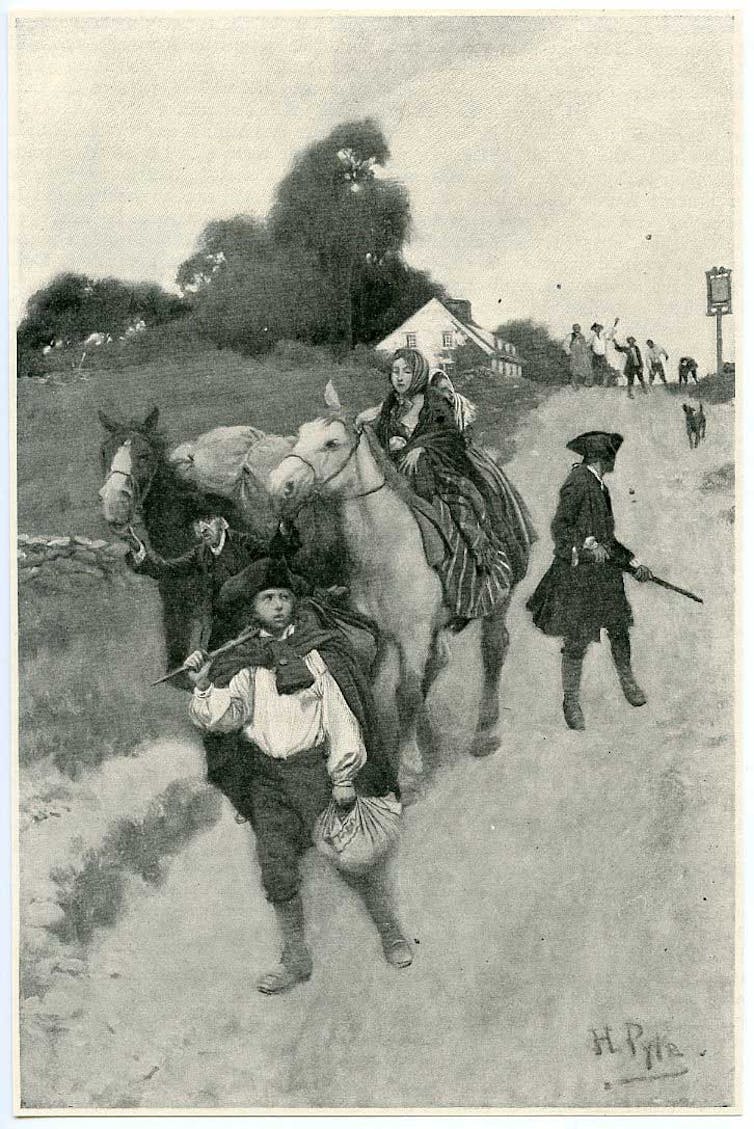

An illustration of Tory refugees heading to Canada after the American Revolution. (Howard Pyle, Atlantic Monthly, via Wikimedia Commons)

Much as with the Afghan refugees, the loyalist diaspora was diverse and did not share a common vision for the social and political organization of the colony to which they had fled after the war. The label “loyalist” suggested a common attachment to the British Empire, but refugee groups were ideologically varied and squabbled constantly with one another and with the colonial government.

John Parr, the exasperated governor of Nova Scotia, complained in a letter to London, “They plague me with complaints, and quarrels among themselves.” Tired of the contest between rival factions, he lamented in another letter, “What an expecting, troublesome being a New England refugee is.”

Meeting New Neighbors

The current debate about resettling refugees within the United States suggests some Americans fear the prospect of living alongside refugees. Despite sharing the same language, religion and customs, British Nova Scotians were also suspicious of the loyalist refugees.

Outnumbered after the war, British Nova Scotians resisted the ascendancy of refugees into political office during elections for the General Assembly in November 1785. They claimed they were worried that the loyalists, like their American counterparts, were, in the words of Gov. Parr, “So strong tinctured with the Republican spirit; that if they meet with any encouragement it may be attended with dangerous consequences to this Province.”

But such rhetoric simply masked the more self-interested fears British Nova Scotians harbored about being dislodged from influential and lucrative positions by refugee lawmakers they worried would favor their fellow loyalists.

The failure to provide for the refugees in Nova Scotia served only to embitter loyalist refugees against the empire. And relations between the United States and the British colonies in Canada remained tense through the early 19th century.

Ultimately, though, family relationships between loyalist descendants in the Maritime provinces of Canada and the New England states helped facilitate important economic connections and forged lasting ties that brought the two regions closer together. The children of Afghan refugees, who may well have family that remained in their home country, might also prove valuable in future relations between the two nations.

G. Patrick O’Brien is a lecturer in history and philosophy at Kennesaw State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Au début du 19e siècle, les Cantons de l’Est au Québec étaient la région la plus riche du Québec occupé par le Canada de l’époque; les loyalistes avaient été grassement dédommagés.

Thanks for illuminating this forgotten dark corner of our history. For further reading I would suggest Jasanoff’s “Liberty’s Exiles” (Harper, 2011). Fully ten percent of the inhabitants of the colonies chose to flee rather than trust the vague promises of “liberty” mouthed by men inspired by atheistic French philosophes to take up arms against a king whose right to rule them derived from almighty god himself.

> king whose right to rule them derived from almighty god himself.

The “divine right” of kings was thoroughly abandoned in the UK by then. More than a century before, Parliament had made that clear by chopping off the King’s head…. And the Restoration that followed was short-lived. They invited a foreigner in to become king, largely on their terms. By the time of the American Revolution, it was the aristocracy (and to some extent the rich bourgeoisie) who ruled through Parliament.

Thanks. Very informative!