During this week’s commemoration of the attacks on Japan, Nozomi Hayase spotlights the courage of two journalists — Wilfred Burchett and Julian Assange — who sacrificed their own freedom to expose war crimes.

War Crimes, Empire and the

Prosecution of the Free Press

By Nozomi Hayase

Special to Consortium News

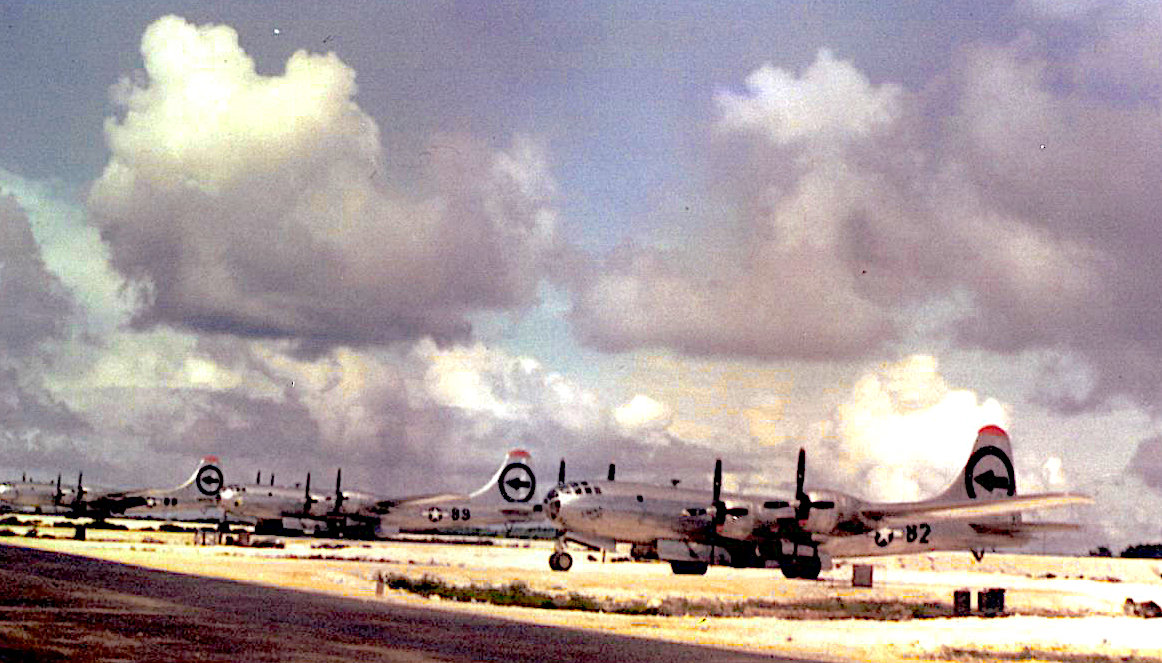

Aircraft that took part in the Hiroshima bombing; Tinian Island, 1945. Left to right: Big Stink, The Great Artiste, Enola Gay. (Harold Agnew, Wikimedia Commons)

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the detonation of U.S. nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (Aug. 6. 1945) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9) during World War II.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the detonation of U.S. nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (Aug. 6. 1945) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9) during World War II.

The death toll of the two atomic assaults has been estimated at over 225,000 people, with many killed instantly, while others died later from radiation exposure.

In the aftermath of the bombing of Japan, and for decades afterward, U.S. authorities suppressed the military footage shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to curvature of Earth. Angles and locations approximate. Kokura included because it was original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility and so Nagasaki was chosen as backup. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons)

With government propaganda and censorship, the public was kept in dark about the scale of damage and human suffering inflicted. The U.S. nuclear strike turned Japanese soil into a toxic disarray where nothing would grow for another 75 years. Contrary to its declared target (the Japanese Army headquarters), the bomb blast seared people to death: women, children and elderly, and those who weren’t in a uniform, indiscriminately causing long-term health effects in those who survived the blast.

British investigative journalist Robert Fisk once said, “War is a total failure of the human spirit.” The fallout of the atomic bomb represents the fall of humanity and loss of its dignity. It has not only taught people all over the world about the horrors of nuclear weapons, but also emphasized the crucial role of the media in preventing terrible human errors during a time of war.

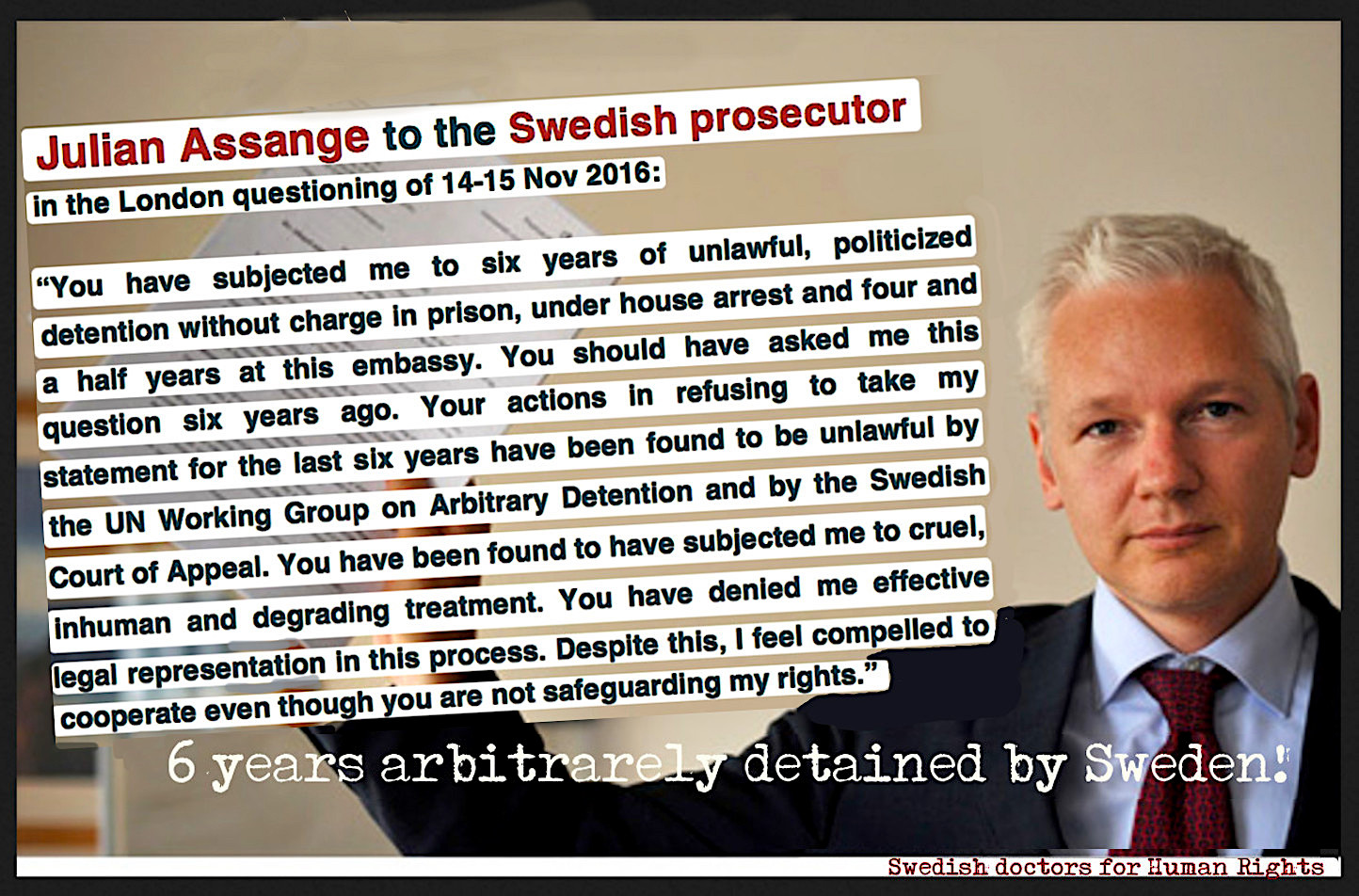

In recent years, under the Trump administration, the free press has become severely threatened. On numerous occasions, President Donald Trump has expressed outrage at “leakers,” and media organizations using such leaks to disclose classified information. With the U.S. government’s prosecution of WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange, the hostility of the Trump administration toward the media has now escalated into criminalization of journalism.

Wilfred Burchett’s Warning

Assange has been indicted on 17 counts under the Espionage Act of 1917 and one charge of conspiring with a source to violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act for his reporting on the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the torture committed at Guantanamo Bay. Assange is being held on remand in Belmarsh Prison, solely on the basis of a U.S. extradition request. He would face 175 years in prison if convicted.

Julian Assange outside UK Supreme Court in 2011. (Flickr)

Assange’s extradition is recognized by free-speech groups as the most important press freedom case of the 21st century. What is this prosecution of a publisher really about? The story of an Australian journalist who exposed the brutal truth of war at the end of WWII can provide a historical context and help us better understand the significance of this case.

Wilfred Burchett has become known as the first Western journalist to enter Hiroshima after the city was bombed, where he reported from one of the few hospitals operating. In the story headlined “The Atomic Plague,” Burchett wrote, “Hiroshima looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence.” The Melbourne war correspondent indicated that civilians were suffering from more than big blisters with their hair falling out.

Burchett’s dispatch — often referred to as the “Scoop of the Century” — was denied by the U.S. administration. The deputy head of the Manhattan Project utterly dismissed it as Japanese propaganda. Burchett’s firsthand, on the ground, eyewitness account was also criticized in his home country, Australia.

Burchett’s dispatch — often referred to as the “Scoop of the Century” — was denied by the U.S. administration. The deputy head of the Manhattan Project utterly dismissed it as Japanese propaganda. Burchett’s firsthand, on the ground, eyewitness account was also criticized in his home country, Australia.

A documentary film “Public Enemy Number One” (1981) produced by David Bradbury showed how Burchett was accused of supporting “the other side” in Australia. The film posed the questions: “Can a democracy tolerate opinions it considers subversive to its national interest? How far can freedom of the press be extended in wartime?” Sadly, the enquiry seemed to have fallen on deaf ears and silence has long since prevailed.

Pushing Boundaries of Free Speech

Decades later, another Australian came forward to respond to this call. Julian Assange, through his work with WikiLeaks, began again pushing the boundaries of free speech.

WikiLeaks published a secret trove of U.S. classified military records of the Afghan war, revealing around 20,000 civilian deaths by assassination, massacre and night raids, followed by the “Iraq War Logs,” which informed both Iraqis and the international community about 15,000 previously unreported civilian casualties.

One of the most significant examples of uncompromising public-interest reporting was WikiLeaks’ release of classified U.S. military footage depicting the July 12, 2007, Baghdad airstrikes against unarmed civilians. The attack killed a dozen innocent civilians, including two Reuters’ journalists, Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh.

The publication of the “Collateral Murder” video shattered the sheltered American view of reality, shocking everyone who has been made to think that the Iraq War was over. Dean Yates, a journalist who was in charge of Reuters’ bureau in Baghdad, learned for the first time of the real nature of the U.S. Army’s bloody killing of his Iraqi colleagues via the WikiLeaks video.

Equating the significance of the “Collateral Murder” video with the Abu Ghraib photos showing U.S. atrocity and the real cost of war, Yates explained that “the U.S. military had repeatedly lied to him – and the world – about what happened.” He continued, “Assange brought the truth of the killings to the world and exposed the lie that he and others had not.”

Enemy of the State

Wilfred Burchett. (From the cover of his autobiography, “At the Barricades.”)

Burchett, a veteran reporter for the UK’s Daily Express, believed that a duty of journalists is to be independent from doctrines and political ideologies and that their responsibility is to get facts right and publish the truth. For his fierce commitment to performing this duty, he became a controversial figure. He was ostracized and turned into public enemy No. 1. Australian media depicted him as a traitor and his fellow countrymen turned against him. The Australian government deprived him of his passport for 17 years and he was barred from his own country.

Assange, who is a longstanding member of Australia’s journalists’ union and is a recipient of dozens of prestigious journalism awards, also displayed a similar sense of journalistic duty. He described his organization’s commitment to “publish information that informs the public, even if many, especially those in power, would prefer not to see it.”

Assange’s efforts to defend the public’s right to know have created conflicts with powerful states. After WikiLeaks’ disclosures of numerous U.S. government’s war crimes, the Pentagon attacked the whistleblowing site; accusing it of damaging national security. U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen, the top U.S. military officer, used the bombastic line of “blood on their hands,” calling the WikiLeaks publications “reckless and irresponsible,” even though not one single shred of evidence has ever been brought forth that any of these disclosures caused anyone harm.

From the bogus preliminary investigation of his alleged sexual misconduct in Sweden (the investigation was finally discontinued in 2019) to vilification and character assassination by high profile figures in the U.S., Assange — as the face of the organization — came under massive political attack. He was arbitrarily detained inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London for over seven years, where he was deprived of medical care and sunlight by the U.K. government’s refusal to honor his asylum right — despite repeated warnings from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. For years, while he was inside the embassy, Assange was spied on by a Spanish security contractor. The contractor, ostensibly, was working for the government of Ecuador, but was allegedly also secretly working on behalf of the CIA. Surveillance through video cameras and audio operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, extended to privileged conversations between Assange and his lawyers and doctors, as well as with journalists and friends. The spying even operated inside the women’s bathroom.

Despite the enormous injustice levied on its own citizen, the Australian government remained subservient to its Western ally, leaving Assange feeling completely abandoned. Exiled by his own country, Assange became a world-famous political prisoner. He is moldering in a maximum-security prison London’s, where he is being psychologically tortured, as indicated by UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Nils Melzer and medical doctors who assessed him. Over 200 physicians and psychologists from 33 countries have signed an open letter calling out the Western governments’ coordinated abuse of power against the journalist and demanding an end to Assange’s torture and medical neglect.

Despite the enormous injustice levied on its own citizen, the Australian government remained subservient to its Western ally, leaving Assange feeling completely abandoned. Exiled by his own country, Assange became a world-famous political prisoner. He is moldering in a maximum-security prison London’s, where he is being psychologically tortured, as indicated by UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Nils Melzer and medical doctors who assessed him. Over 200 physicians and psychologists from 33 countries have signed an open letter calling out the Western governments’ coordinated abuse of power against the journalist and demanding an end to Assange’s torture and medical neglect.

No Path to Peace

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki marked the end of World War II. Military officials announced that the United States had defeated Nazi Germany and Japanese imperial aggression. The foreign minister of Japan, representing the emperor, signed the surrender agreement in the Bay of Tokyo on Sept. 2, 1945. “May peace be restored,” said General MacArthur, U.S. supreme commander of the occupation of Japan, at the formal ceremony.

Yet, the flash of light which had emanated from an American B-29 bomber didn’t illuminate a path toward peace. It blinded the eyes of both Japanese and Americans, preventing them from seeing each other truly; recognizing their shared humanity. The use of nuclear weapons by Americans, the justification for which was to hasten the end of the war and avoid further allied casualties, brought a total devastation of Japanese cities and their residents. It created trauma and irreparable moral injury in American soldiers. In the critical hours that led to the decision of the U.S. government to drop nuclear bombs on Japan, were any alternatives considered, especially as that country was already at the point of surrender?

Wilfred Burchett, the son of a Methodist lay preacher who helped rescue Jews from Nazi Germany, did raise other possibilities. While Allied journalists dutifully covered the official Japanese surrender aboard the battleship, flocking around General Douglas MacArthur’s occupation headquarters in Tokyo, Burchett boarded a train to Hiroshima — alone and unarmed. Carrying seven meals, a black umbrella and his typewriter, he traveled 400 miles from Tokyo in a search for truth in the bombed Hiroshima — to recover images of dead and wounded bodies of innocent civilians buried by the mainstream media.

Burchett’s honest coverage of nuclear holocaust across the Pacific Ocean challenged the official story; one which glorified the U.S. victory over Japan. His journalism gave voice to the silenced, allowing the victims of a terrible day of destruction to tell their side of the story.

Scenes of Hiroshima turned into a living hell confronted the hypocrisy of the U.S. government, revealing its own brand of terror unleashed in the name of defeating fascism overseas.

Mightier Than the Sword

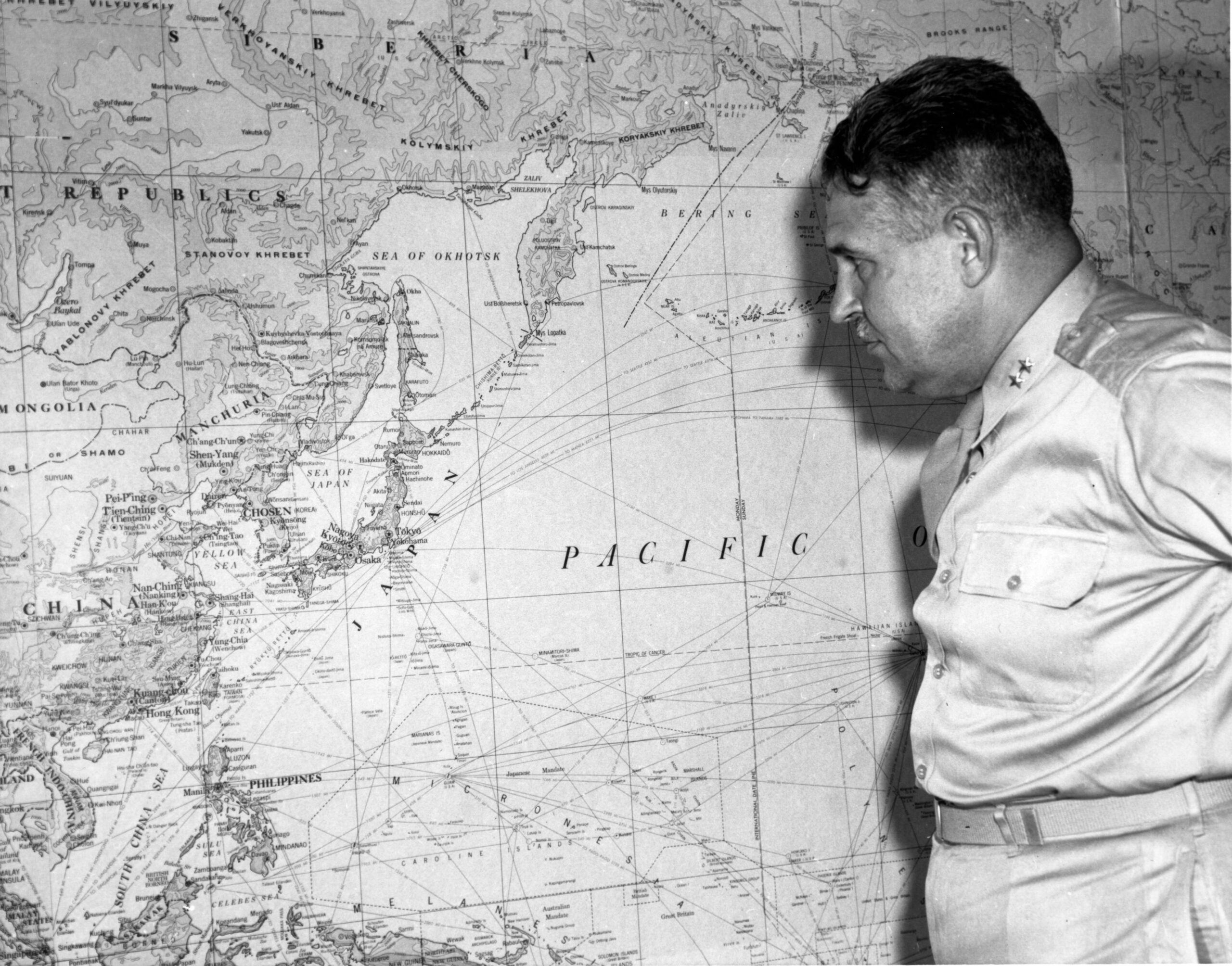

Burchett’s reporting from the other side showed how the free press could become a shield to protect innocent civilians, and could be used by ordinary people to stand up against the arsenal of the powerful. Through his journalistic activities, he aimed to convey the truth contained in the old adage “the pen is mightier than the sword.” His writing warned that power cannot be tamed by power.

Burchett tried to show the U.S. and its Western allies that the sword of imperial Japan, expanding its dominance over East Asia, cannot be destroyed by guns, missiles or even the A-bomb.

Leslie Groves, Manhattan Project director, with a map of Japan. (U.S. Government, Wikimedia Commons)

His message was that peace cannot be won by conquest; by military might, or through forced surrender and treaties. Power begets power. Peace can be only possible through our striving to understand our differences through dialogue and diplomacy.

Now, in the age of the internet, with a computer in hand, Assange used the free press as a nonviolent weapon to challenge the military industrial complex. WikiLeaks, through the method of transparency, empowered ordinary people with knowledge. They opened state secrets to the democratic gaze, providing an alternative means to solve conflicts other than violence and coercion.

Uncensored images of modern war, made available by whistleblower Chelsea Manning’s act of conscience, provided perspectives that had been masked by the euphemism of “collateral damage.” American people were able to see the real faces of those who had been previously described to them as “enemy combatants” — children, women, ordinary civilians and even animals.

From Hiroshima to Baghdad, Burchett and Assange, two Australian journalists generations apart, confronted the cruelty of nuclear arms and the machinery of war with love for humanity. With great courage, they tried to demonstrate that the only way to truly end the war is through nonviolence.

Redemption of Our Own Dignity

The clothes pattern, in the tight-fitting areas on this survivor, shown burnt into the skin. (U.S. National Archives, Wikimedia Commons)

At the birth of the United States of America, the framers of the Constitution departed from the practice of the British monarchy by laying the principle of free speech as the core foundation of government, with a free press positioned as a critical safeguard against tyranny.

The prosecution of Julian Assange is a direct attack on the First Amendment. The outcome of this not only determines the future of journalism, but also of our democracy. The use of violence to secure peace has only made the world more dangerous and destructive. The explosion of “Little Boy” on Hiroshima early one hot summer morning in 1945 began a nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. From the Korean War to the Vietnam and Gulf Wars, the U.S. expanded its occupying forces, becoming a superpower.

Now, the empire — which covered up its dirty war in the Middle East — desperately tries to prevent the public from knowing the truth behind its prosecution of a journalist who exposed their crimes. According to Assange’s lawyers, the U.S. may soon drop its existing extradition request and then re-arrest him on the same 18 charges after a new extradition request.

I spoke to Julian today. At any moment we expect that the US will drop its existing extradition request and then re-arrest him on the very same 18 charges, under a different extradition request.

We don't know if this means he'll be brought to court to be 're-arrested'. (Thread)

— Stella Assange #FreeAssangeNOW (@StellaMoris1) July 28, 2020

While it is intensifying assaults on press freedom, the Trump administration has now withdrawn from the Treaty on Open Skies, designed to prevent an accidental war, making the world more vulnerable to the threat of nuclear annihilation.

This week, as we commemorate the world’s first atomic bomb attack of 75 years ago, it is important to remember the courage of journalists who sacrificed their personal liberty in their attempts to enable us to confront our failures and redeem our own dignity.

Assange’s extradition hearing starts in a London court on Sept. 7. In this crucial month of August, before the trial of journalism begins, we are all called to stand up for those who have upheld freedom of speech as an alternative to our tragic past. Together, let us find strength, and our own courage in defense of free press. Let us choose a way of peace that could lead to our realization of liberty and equality of all people.

Nozomi Hayase, Ph.D., is an essayist and author of “WikiLeaks, the Global Fourth Estate: History Is Happening.” Follow her on Twitter: @nozomimagine

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’

on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

As always: high standard article from the autor.

From the civil societies around the globe, we share our thoughts with the civil societies of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the volkgeist of the Japanese people. Thoughts to them who had no chance of defending themselves, to the fathers and mothers who were occupied caring for their children. At least in other bombings of civil societies, historically, at least there has been a theoretical chance of seeking refuge, or to take up arms and fight. These possibilities was in these two instances impossible. May humankind avoid this happening again, even when the last living survivors has passed – and hopefully the memories in mankinds collective memory will be enough. But if we are not allowed to speak, more or less freely, chances are, at best, slim. /Yours Truly

The US pretended that the Japanese would not submit to unconditional surrender – yet the Emperor business was the only condition (and one that as it happens the US went along with anyway). Why? Because the Truman admin was virulently anti-Soviet and the USSR had agreed to join in the fight against Japanese and do so on a date that would have been after the bombs were dropped. FDR got on reasonably well with Stalin, much to the Soviet phobes (including Churchill) consternation.

The nuclear bombs used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki were intended as a demonstration to the USSR’s government: “See what we’ve got…” And this fact (again there has been a fair bit of historical research on this by reputable historians and is readily available) makes the production and use of these bombs even MORE despicable, more amoral…

My second quibble regards your singling out the Strumpet with regards to Mr Assange (and remotely similar cases). Now the Strumpet is a total arsehole, one who perceives being Prez as akin to being the Boss in The Apprentice interwoven with his bombastic real estate dealing persona. And he is totally objectionable and inhumane.

BUT he’s hardly the first inhumane, immoral, Moloch-Mammon worshiping Prez. And the attack on whistleblowers began seriously not under the Strumpet, but under the smooth talking, well dressed, slim Mr Obama. Indeed I do believe he (his admin) began the case against Assange.

Excellent article. Thank you!

Dont forget John Pilger who reported on the Vietnam War (which the Vietnamese rightly call the American War). He’s the generation between Burchett and Assange.

Public Enemy Number One (1981)

Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, the first journalist into Hiroshima after the atom bomb, also covered wars in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. He was reviled as a traitor and a communist in the Australian media for reporting the Vietnam War from the perspective of the North Vietnamese.

Filmmaker David Bradbury interviewed Burchett in his later years. Archival footage of the Vietnam War and newsreel footage of Hiroshima after the atom bomb enrich the documentary.

Clips from the film can be viewed on Australian Screen, website of the National Film and Sound Archive (NSFA) of Australia.

To view Clip 1: ‘A warning to the world’, simply Google: “Public Enemy Number One (1981) clip 1 on ASO”

Also Google the essay: “Voice and Silence in the First Nuclear War: Wilfred Burchett and Hiroshima By Richard Tanter”

Tanter writes that “Burchett came to understand that his honest and accurate account of the radiological effects of nuclear weapons not only initiated an animus against him from the highest quarters of the US government, but also marked the beginning of the nuclear victor’s determination rigidly to control and censor the picture of Hiroshima and Nagasaki presented to the world.”