Agricultural workers, farmers and social movements can teach us how the food system should be reorganized during this crisis, write Vijay Prashad and Richard Pithouse.

Kanat Bukezhanov, Coronavirus, 2020.

By Vijay Prashad and Richard Pithouse

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

What the International Monetary Fund calls the Great Lockdown sent 2.7 billion people into either full unemployment or near unemployment, with many people one or two days away from desperate poverty and hunger, according to the International Labour Organization.

Starvation is already evident in many regions of the world. Social movements are doing what they can to organize horizontal forms of solidarity from below, but food riots are already a reality in India, South Africa, Honduras – everywhere, really. In many countries, states are responding with militarized forms of force, with bullets rather than bread.

Before the pandemic, in 2014, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization wrote: “Current food production and distribution systems are failing to feed the world.” That is a damning statement. It needs to be taken seriously. Half-hearted measures are not going to work. We need a social revolution in the world of food that breaks the grip of capital over the production and distribution of food.

Hunger is a bitter reality that modern civilization should have expelled a century ago. What did it mean for human beings to learn how to build a car or fly a plane and not at the same time abolish the indignity of hunger?

The old English reverend Thomas Malthus was wrong when he wrote that, for eternity, food production would grow arithmetically (1-2-3-4) and that populations would grow geometrically (1-2-4-8), with the needs of the population easily outstripping the ability of humans to produce food. When Malthus wrote his treatise in 1789, there were about a billion people on the planet. There are now almost 8 billion people, and yet scientists tell us that more than enough food is produced to be able to feed everyone. Nonetheless, there is hunger. Why?

Hunger stalks the planet because so many people are dispossessed. If you do not have access to land, in the countryside or in the city, you cannot produce your own food. If you have land but no access to seed and fertilizer, your capacities as a farmer are constrained. If you have no land and do not have money to buy food, you starve.

>Please Donate to CNs’ 25th

Anniversary Spring Fund Drive<<

That’s the root problem. It is simply not addressed by the bourgeois order according to which money is god, land – rural and urban – is allocated through the market, and food is just another commodity from which capital seeks to profit. When modest food distribution programs are implemented to stave off widespread famine, they often function as state subsidies for a food system captured, from the corporate farm to the supermarket, by capital.

Jose Tence Ruiz, The Pro-Rated Wage of the Abang Guard, 2011.

Over the course of the past decades, the production of food has been enveloped into a global supply chain. Farmers cannot simply take their produce to market; they must sell it into a system that processes, transports and then packages food for sale at a variety of retail outlets. Even this is not so simple, as the world of finance has enmeshed the farmer into speculation.

In 2010, the United Nations’ former special rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, wrote about the way that hedge funds, pension funds and investment banks overpowered agriculture with speculation through commodity derivatives. These financial houses, he wrote, were “generally unconcerned with agricultural market fundamentals.”

If there is any shock to the system, the entire chain collapses and farmers are often forced to burn or bury their food rather than allow it to be eaten. As Aime Williams writes in The Financial Times of the situation in the United States, these are “scenes out of the Great Depression: farmers destroying their products as Americans line up by the thousands outside food banks.”

If you listen to agricultural workers, farmers and social movements around the world, you will find that they have lessons to teach us about how the system should be reorganized during this crisis. Here is a little bit of what we have learnt from them. It is a mix of emergency measures that can be immediately implemented and more long-term measures that can build towards sustained food security, and then food sovereignty — in other words, popular control over the food system.

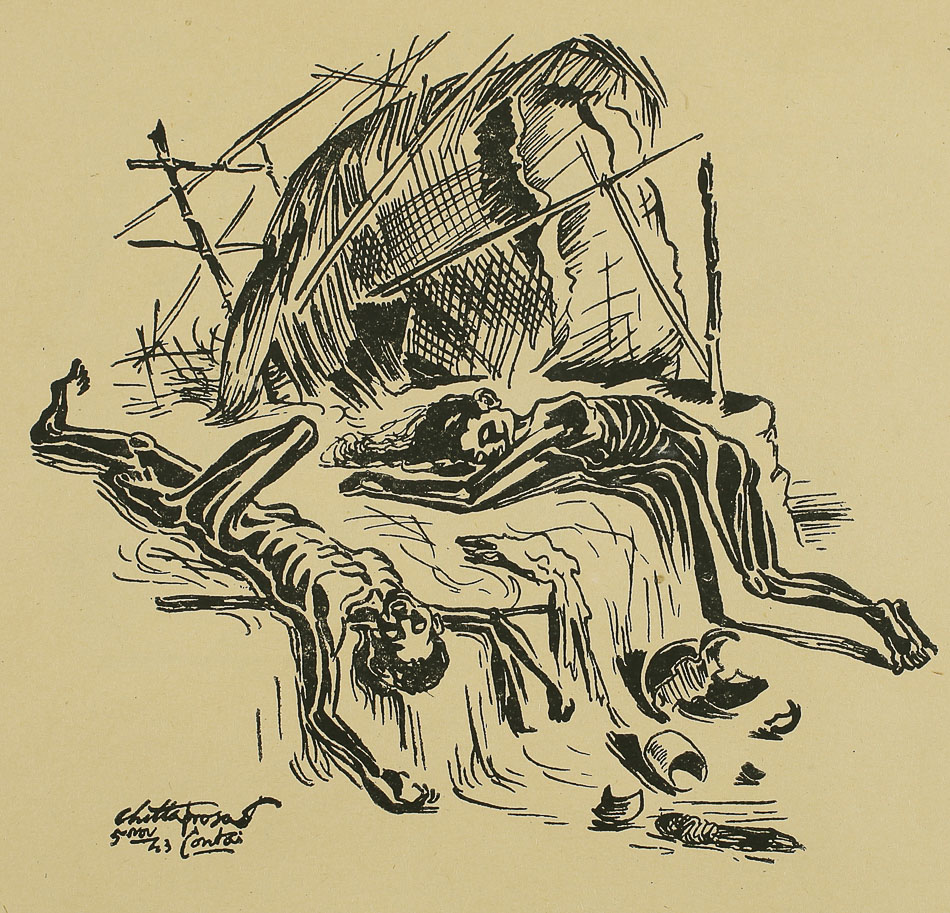

Chittaprosad, Hungry Bengal, 1943.

Enact emergency food distribution. Surplus stocks of food controlled by governments must be turned over to combat hunger. Governments must use their considerable resources to feed the people.

- Expropriate surpluses of food held by agribusiness, supermarkets, and speculators, and turn this over to the food distribution system.

- Feed the people. It is not enough to distribute groceries. Governments, alongside public action, must build chains of community kitchens where people can access food.

- Demand government support of farmers who face challenges to harvest their crops; governments must ensure that harvesting takes place following World Health Organization principles of safety.

- Demand living wages for agricultural workers, farmers, and others, regardless of whether they are able to work or not during the Great Lockdown. This must be sustained after the crisis. There is no sense in looking at workers as essential during an emergency and then disdaining their struggles for justice in a time of ‘normalcy’.

- Encourage financial support for farmers to grow food crops rather than turn to large-scale production of non-food cash crops. Millions of poor farmers in the poorer nations produce cash crops that the richer nations cannot grow in their climate zones; it is tough to grow pepper or coffee in Sweden. The World Bank ‘advised’ the poorer nations to focus on cash crops to earn dollars, but this has not helped any of the small farmers who do not grow enough to support their families. These farmers, like their communities and the rest of humanity, need food security.

- Reconsider the entanglement of the food supply chain, which injects enormous amounts of carbon into our food. Reconstruct food supply chains to be based on regions rather than on global distribution.

- Ban speculation of food by curbing derivatives and the futures market.

- Land – rural and urban – must be allocated outside of the logic of the market, and markets must be established to ensure that food can be produced and the surplus distributed outside of the control of corporate supermarkets. Communities should have direct control over the food system where they live.

- Build universal health systems, as called for by the Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978. Strong public health systems are better equipped to constrain health emergencies. Such systems must have a strong rural component and must be open to all, including undocumented people.

The fact that so many people around the planet, including those living in the richest countries, were going hungry before this crisis is a profound indictment of the failures of capitalism. The fact that hunger is exploding exponentially during this crisis is a further indictment of capitalism.

Hunger is among the most urgent of human needs, and immediate steps need to be taken to get food to people in this crisis. But it is also vital that the social value of land, rural and urban; the means to produce food, such as seeds and fertilizer; and food itself is affirmed and defended against the socially ruinous logic of commodification and profit.

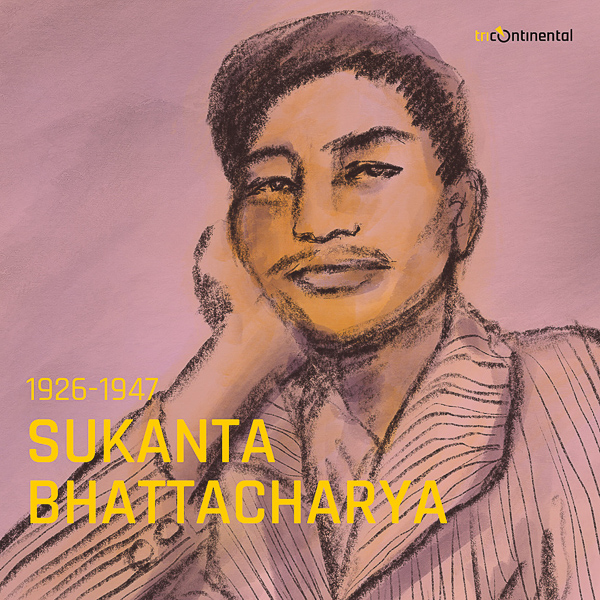

In 1943, the British empire’s bureaucrats took grain from Bengal and left the people in the grip of a terrible famine which killed between 1 and 3 million people. Sukanta Bhattacharya, a member of the Communist Party of India who was 19 at that time, edited a poetry anthology called “Akal” (“Famine”) for the Anti-Fascist Writers’ and Artists’ Association. In this book, Bhattacharya published a poem called “Hey Mahajibon” [“O Great Life!”].

In 1943, the British empire’s bureaucrats took grain from Bengal and left the people in the grip of a terrible famine which killed between 1 and 3 million people. Sukanta Bhattacharya, a member of the Communist Party of India who was 19 at that time, edited a poetry anthology called “Akal” (“Famine”) for the Anti-Fascist Writers’ and Artists’ Association. In this book, Bhattacharya published a poem called “Hey Mahajibon” [“O Great Life!”].

O great life! No more of this poetry.

Now bring the hard, harsh prose.

Dissolve the tender poetic chimes.

Strike the robust hammer of prose today.

We do not need the tenderness of poetry.

Poetry, today you can rest.

A world devastated by hunger is prosaic.

The full moon looks like burnt bread.

Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian, journalist and commentator, is the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the chief editor of Left Word Books.

Richard Pithouse, founder of the People’s Archive of Rural India, is senior fellow at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and coordinator of the institute’s South Africa office.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

>>Please Donate to CNs’ 25th

Anniversary Spring Fund Drive<<

Many issues here. Originally, when the commodity markets formed in the 19th century they actually were a stabilizing factor for an economy: Farmer enters a contract with miller to provide him with grain for a pre-arranged price, miller + baker enters another contract, and baker + retailer enters another. (the chain is actually longer than that). Each year someone profits less and someone else more, and that fluctuates. The losses and gains are absorbed inside the chain.

Compared to a pure agricultural economy, where people starve when the crops are poor this is an improvement.

Enter speculation, where someone purchases one of those contracts hoping it will become more valuable. Farmers do this all of the time. Farmer Joe gets up one morning to find an unusual late frost, calls his broker and enters a trade because he knows before anyone else the frost may cause the price to go up.

Most contracts are bought and sold by traders that never take delivery of the commodity.

I support our family farmers one way or another. Good agricultural land is rare. When it gets zoned for industry that ticks me off.

I disagree with the authors that governments should be involved in markets of any kind. Here’s a quote from Ann rand:

“When you see that in order to produce, you need to obtain permission from men who produce nothing… when you see corruption being rewarded and honesty becoming a self-sacrifice, you may know that your society is doomed.”

There are enough farmers to grow enough food for all, but what if farmers can’t get access to land? If it’s over-priced and the asking amount for purchase or to rent is too high for the farmer to afford? Many know that besides making farming possible, land itself can be an investment, like stocks and bonds. People speculate in land, buy it cheap and hold it; don’t sell until prices in the area have risen to make a profit possible. Since land is the life blood of people, many have seen land speculation as more evil than speculation in things, commodities, etc. Land is our source of life, and people, especially farmers but also home builders, companies that create physical things to sell, should not be locked off the land by high prices set by land speculators who try to buy low and sell high. That’s OK for stocks and bonds, but not for land, the life blood of the human race. The American economist Henry George (1839-97) introduced his “Single Tax on Land Values” in his best-selling “Progress and Poverty” (1879), as the way to prevent deadly land speculation. P&P became a world-wide best-seller and was translated into most world languages. The Single Tax on land values would keep land rents and prices low so that access to land would be guaranteed to both farmers and all wealth-producers: home-builders, factory owners, etc. I asked at my local Ivy university’s Economics dept. if George was taught to Econ majors and the answer was that he is mentioned in passing, but not much more. The fact that many big donors to colleges and universities are often large speculators in land markets and/or real-estate stocks may have something to do with why George’s anti-poverty remedies are given short shrift in academia. But many great minds have written appreciations of George, including Albert Einstein, John Dewey, Helen Keller, Milton Friedman, Franklin D. Roosevelt, to name just a few. “Progress & Poverty” is at most libraries, but sorry to say it may be hidden away in the stacks!

And not only that, climate change is wreaking havoc on anyone growing food. The small garden I tend was flooded so many times last year during the wettest year on record, that the yield was terrible in quality and quantity, and we just had 6 inches of rain one one day yesterday so it just keeps getting worse and worse and more and more difficult to even produce food with the extremes of climate. Seeing farmers dump perfectly good milk down the drain and plowing their crops back into the ground is disturbing on a visceral level, and a sure sign that confirms the writer’s premise that something is really wrong with the logistics and distribution of food. Seems like, just as with money, food trickles up to the rich, leaving the 99 percent with less and less.

Thanks for putting food/commodities in a clear light – for years I’ve looked as distribution/transportation as the basic ill without looking at funds and derivatives.

Your list of emergency measure will hopefully be adopted universally and locally.

The MAIN CULPRIT behind all of the covid19 virus mayhem is Great Britain & dirty gov’t. leaders of other countries(including the U.S.A) The British Empire or European Union has NEVER been a true ally of any country. Lyndon B. LaRouche knew this & tried to warn MANY others of their conspiracies, but Mueller & Kissinger worked together to put LaRouche behind bars on false accusations made by them at the British Empire’s request. BRITS WANT POWER & CONTROL & MONEY as do many others, and are willing to kill MANY innocent souls to gain it!! Look what they’re doing to Africa at the time.