John Wight says grim British living standards ensure that the general election next month is the most important in a generation.

By John Wight

in Edinburgh, Scotland

Medium

One million people, many of them in work, forced to rely on foodbanks; 1 in 4 children living in poverty; homelessness, including rough sleeping, at a 30-year high; real wages down; the worst housing crisis of any advanced industrialized economy; the NHS in crisis; the most ramshackle, anarchic and expensive rail system in Europe; the highest prison population in western Europe; crime up; suicides up — all this as as the combined wealth of the richest 1000 people in Britain increased by 183 percent over the same decade in which 120,000 people have died as a direct result of austerity.

One million people, many of them in work, forced to rely on foodbanks; 1 in 4 children living in poverty; homelessness, including rough sleeping, at a 30-year high; real wages down; the worst housing crisis of any advanced industrialized economy; the NHS in crisis; the most ramshackle, anarchic and expensive rail system in Europe; the highest prison population in western Europe; crime up; suicides up — all this as as the combined wealth of the richest 1000 people in Britain increased by 183 percent over the same decade in which 120,000 people have died as a direct result of austerity.

This grim toll ensures that the general election on Dec. 12 is the most important and seminal in a generation.

Brexit of course will figure front and center for many people when casting their vote. The issue has polarized British society over these past three years, corroding social cohesion as the country grapples with what is inarguably the most severe political and constitutional crisis it has faced in generations. What is crucial to grasp is the fact that Brexit is not in a Tony Benn exit from the EU. Instead it is a disaster capitalist project of the right, dripping in nativism, English nationalism and xenophobia, exposing the dire consequences of a country that has yet to honestly or properly address its colonial and imperial past.

Labour’s Fortunes

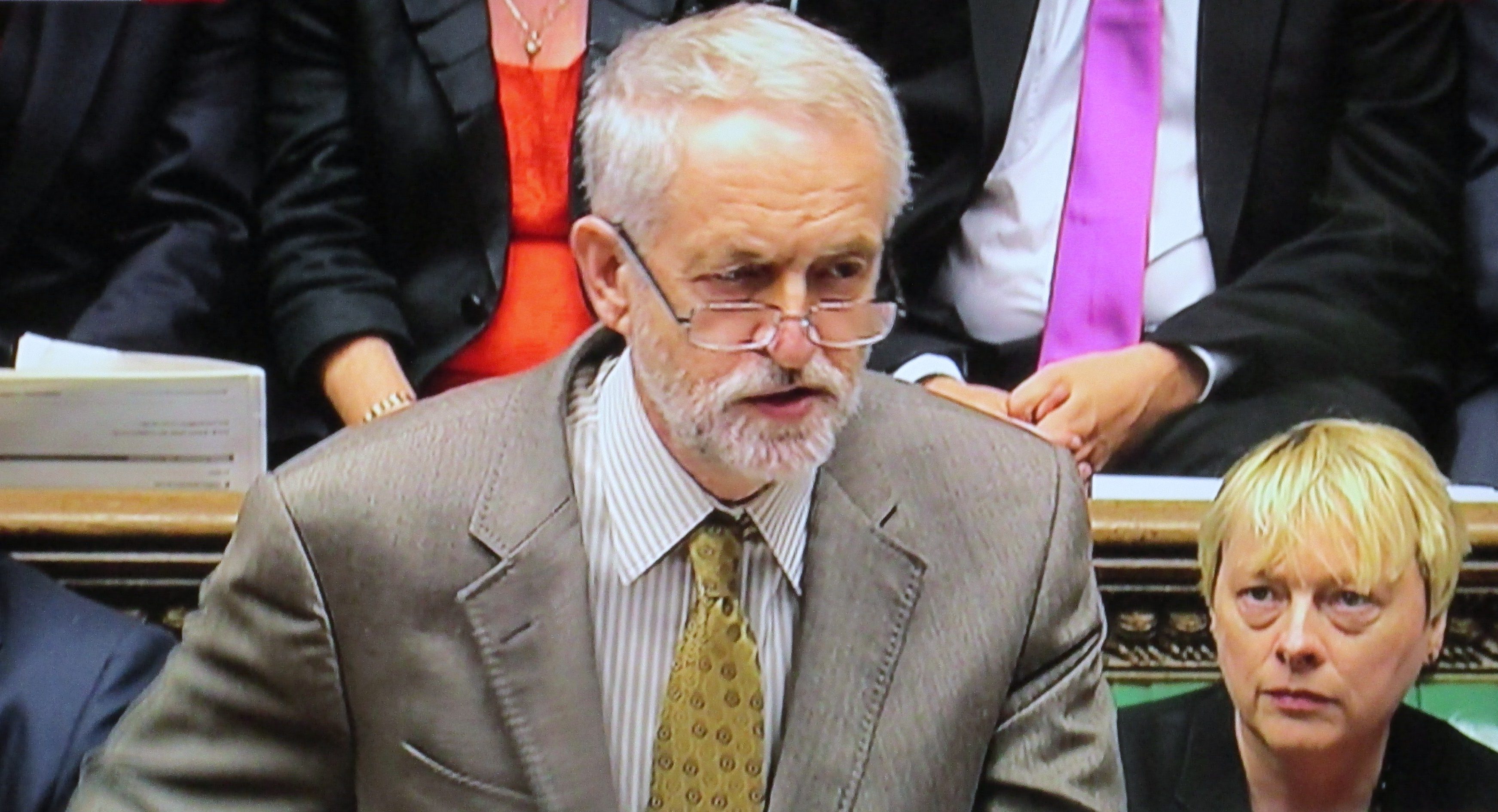

Jeremy Corbyn. (David Holt via Flickr)

But, no matter, Labour and Jeremy Corbyn’s fortunes in this election will be bound up not with Brexit or even Corbyn’s personal qualities as a putative prime minister. Instead, as in 2017, Labour’s fortunes will be bound up with their manifesto for transformational change.

If this manifesto is anything like the one Labour fought the election on two years, it will be one that plants its colours squarely on the side of working people, the low waged and the vulnerable, pledging to reverse decades in which successive governments have worshipped at the altar of the free market, allowing blind economic forces to dictate every aspect of government policy, embracing thereby the economy as a tyrant over the lives of ordinary working people rather than as a servant of their needs.

In this regard austerity, rolled out as the answer to the global financial crash of 2007–08, had absolutely nothing to do with economics and everything to do with ideology — specifically the unleashing of a class war with the objective of transferring wealth from poor and working people to the rich and affluent, using the crash as a pretext.

The Price We Pay for Civilization

The Tory political and media establishment accuses Corbyn of wishing to drag the country back to the 1970s, a supposed decade of doom and gloom in Britain. This is nonsense. I grew up in the 1970s and for working people it was a veritable paradise compared to today. Free dental care, eye care, school meals for all children, decent wages and conditions, trade union rights, a sense of community that is sorely lacking now. And thinking about it, to label these things as “free” is a misnomer. They weren’t free. They were paid for out of general taxation — and taxation, as every smart person knows, is the price we pay for civilisation.

Yes, there was a rising tide of industrial action by the unions, but in contradistinction to the right’s historical narrative of the period, this labour unrest came about in response to the spike in inflation that had arrived on the back of the liberalization of the global financial system, beginning in the early 1970s and exacerbated by the Nixon administration’s decision to abandon the gold standard in 1971. This measure was taken in response to the economic drain on the U.S. economy and the value of the dollar internationally as a result of the war in Vietnam. The result for British workers was downward pressure on wages.

Yes, there was a rising tide of industrial action by the unions, but in contradistinction to the right’s historical narrative of the period, this labour unrest came about in response to the spike in inflation that had arrived on the back of the liberalization of the global financial system, beginning in the early 1970s and exacerbated by the Nixon administration’s decision to abandon the gold standard in 1971. This measure was taken in response to the economic drain on the U.S. economy and the value of the dollar internationally as a result of the war in Vietnam. The result for British workers was downward pressure on wages.

As revealed by Cambridge academics Ken Coutts and Graham Gudgin in a report on this causation: “The freeing up of finance led to a huge, and eventually unsustainable, expansion of household borrowing. This temporarily accelerated the growth of consumer spending and hence GDP and of house prices, but in 2008 contributed to a banking crisis and the longest recession for over a century.”

Later in the same report, on the issue of industrial relations, the authors have this to say:

“Common sense indicates that less [industrial] disruption should be a good thing in itself but not necessarily if the result has been a weakening of wage bargaining power that has allowed a resurgence of extreme income inequality. We note that the UK economy grew consistently and well through the 1950s and 1960s even with poor industrial relations, as it did in the USA with extra-ordinarily high strike levels by British standards.”

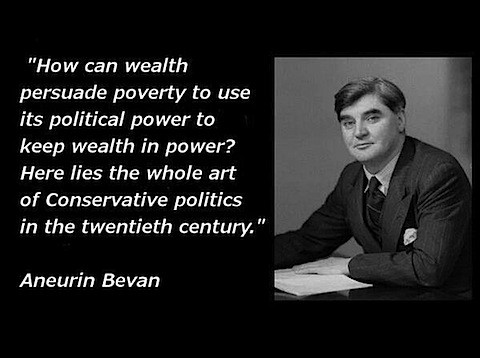

Corbyn, with a manifesto that will do less to drag Britain back to the 1970s and more to move it out of the 1870s, has reignited the kind of class and political consciousness we haven’t seen in decades, challenging three decades of permanent government of the rich, by the rich, and for the rich. And it is for this reason that he’s been so fiercely attacked and demonized by those whose power and privileges are predicated on mass political somnolence.

Meanwhile, when it comes to foreign policy, just consider the difference between a government that slavishly attaches itself to the coattails of President Donald Trump in Washington and a leader of the opposition who, if elected prime minister, will not. And this is without taking into account the prospect of bringing a long awaited curtain down on the disgraceful cozying up to a bloodsoaked Saudi kleptocracy, blind support for the apartheid State of Israel, and the propensity for military instead of diplomatic intervention as a means by which to sustain influence on the world stage.

In 2010 the Tories came to power and unleashed war on society, turning the lives of millions of British people and their families upside down in service to a callously and consciously cruel belief that poverty marked out its victims as perpetrators of their own condition. Thus the demonisation that accompanied austerity shaped public apathy if not consensus when it came to its implementation as being necessary in order to trim the fact of a bloated public sector and purify the poor and disadvantaged with pain.

We may not be materially affected by austerity, by food banks, benefit sanctions, zero hours contracts, and by attacks on the disabled. However our humanity obliges us to be offended by it. You don’t have to be a migrant to resent their depiction as the enemy within. And you do not need to be among the ranks of growing number of rough sleepers on our streets to understand that no one should be allowed to fall that far. The savage consequences of austerity impacts all of us; the normalization of so much injustice and cruelty chips away at our own humanity, and that more than anything is unforgivable.

It is why, if nothing else, the success of the Tories in turning us into passive spectators of the mass experiment in human despair they have inflicted on the most vulnerable in society should be foremost in our minds when we cast our vote on Dec. 12.

John Wight is an independent journalist based in Edinburgh, Scotland.

This article was first published on Medium.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will be removed. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments.

Too bad Corbyn can’t take a straight stance on Brexit, though. THAT, not intra-Labour fighting, will be at least half of why they slump at the polls. He should have resigned if he couldn’t follow the party conference and take a straight and ardent stand on Remain at the time of the referendum.

‘Instead, as in 2017, Labour’s fortunes will be bound up with their manifesto for transformational change.’

JC can’t save us. His pledges amount to nothing more than another spin on the reformist misery-go-round and include expanding wage slavery as well as a million new homes being built over five years. Yet no Labour government has ever left office with unemployment lower than when it started and after World War II (Labour has supported all wars since WWI – bang goes the peaceful foreign policy pledge!) Bevan promised to solve the housing problem. Other pious pledges include ‘security at work’ (recall the use of troops as strike breakers against the dockworkers) and a secure NHS. Labour Minister Bevan felt more secure with his own private physician, and with the introduction of charges for dental and optical services he resigned, failing to say ‘that’s capitalism folks!’ Tuition fees? That was Labour too. Do not bank on the pledge for them to be reversed! The climate change pledge? That’s likely to be just hot air. Free transport? No, nothing more than the possibility of an expanded publically-controlled bus network. Apparently, FTSE 100 CEOs are now paid 183 times the wage of the average UK worker. Expect a redistrubtion of crumbs, nothing more. Emphasis on human rights? Your right to be exploited is guaranteed under Labour!

This whole article seems upside-down to me (however I am not a Brit). Corbyn had a better chance to bring about social justice by leaving the EU. The EU is a neo-liberal dominated institution. Its ideology and rules prevent Corbyn from bringing about the social changes he would like. His natural constituency of working-class people voted to leave. He should have gone all-in with the Brexit people. It may have offend his personal sensibilities to go along with people who don’t want England include to be a little bit of India, a little bit of Arabia, a little bit of Africa, … and a very little bit of England.

Plucking Obama out of the ether and comparing him to Corbyn; can you imagine Corbyn telling the fraudulent bankers that he will protect them from the pitchforks and then bail them out with trillions?

Plantman this is bad mouthing and right wing hubris, turn the disgrace back on yourself.

This article begins with harsh facts:

Many working people forced to rely on foodbanks.

High percentage of children living in poverty.

People forced to live on the street, at a decades-long high.

Real wages down.

Epidemic housing crisis.

Healthcare system near collapse.

Ramshackle rail system (where it exists at all).

Biggest prison population.

Rising suicide rate.

Soaring concentration of wealth.

Hmm… Brings to mind a another nation we know.

“But both men completely fake. I can see that now.”

To compare Corbyn,with over forty years of REAL Labour policies and honesty, with Obama, shows US contempt for any real decent political candidates, not beholden to bribery.

The advisory referendum, the word all the leavers forget is advisory, I will leave it up to you to look up the meaning of this word for yourself.

It was not ‘advisory’

All remainers will spin anything that makes them look good!!

The outcome of the referendum was to be honoured, despite Cameron’s despicable claims and resignation.

The referendum outcome was supported by all parties in the futile 2017 election and, in principal has been supported ever since until labour and limpdems suddenly found anti-democratic democracy

How many times is this question going to be raised – until we all agree with you, perhaps, let’s have another referendum to prove it, hey??

A very good diagnosis of the state of little Britain. It won’t be long before little Britain will be a bona fide banana republic. Exciting future, won’t you say, eh?

Brexit was passed in June 2016, 51.9% to leave, 48.1% to remain. The Global Elites and their minions hated that vote, so nothing has happened in 3 1/2 years, and likely never will.

You can be certain that if it had been another tax break for the Global Elites, it would have been implemented over 3 years ago.

The author says–“Brexit is not in a Tony Benn exit from the EU. Instead it is a disaster capitalist project of the right, dripping in nativism, English nationalism and xenophobia.”

Wrong. Brexit is the defining issue of the election and regrettably, the Labor party is on the wrong side of the issue. Labor has decided to block Brexit at all cost despite the referendum results, despite the clearly articulated will of the people, and despite the fact that 5 million of its own voters supported the initiative. Why talk about all the wonderful things you want to do for “poor and working people’ if you condescendingly brush aside their vote as a sign of “nativism, English nationalism and xenophobia.” That is precisely the kind of elitist nonsense that alienated liberals across the center of the United States and turned them into reliable Trump supporters. Now Labor is following that same pattern.

The author says–“In 2010 the Tories came to power and unleashed war on society, turning the lives of millions of British people and their families upside down in service to a callously and consciously cruel belief that poverty marked out its victims as perpetrators of their own condition. ”

What a bunch of baloney. Is he trying to convince us that neoliberalism and grinding austerity has been a conservative project alone?? Well, it hasn’t been, not by a long shot. Tony Blair and Barack Obama have been just as eager to implement “reforms” that hurt working and poor people just as much as Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. The liberals are just more cagey in the way they put the policies in place.

Don’t get me wrong, I was sucked into Jeremy Corbyn’s orbit just like I was with Obama. But both men completely fake. I can see that now.

I won’t go into Obama’s pathetic record, but suffice it to say he never lifted a finger for black people, working people, or any other people other than Wall Street bankers.

As for Corbyn, he has done everything in his power to block the Brexit referendum because he knows better than the 17 million people who voted for it, because it doesn’t jibe with Marxist-internationalist pretensions, and because he would rather see Britain in the grips of a thoroughly-corrupt and undemocratic European superstate that free to control its own borders, its own waters and write its own laws.

The man is a disgrace.

“despite the clearly articulated will of the people”

Britain is pretty much evenly split between leave and stay. Far from ‘clearly articulated will of the people’. The leave side clearly and blatantly lied about Brexit and leaving is far more complicated that you appear to believe. Not sure how you get that Corbyn has ‘Marxist internationalist pretensions’, he wants a return to social democracy and a country where people earn enough money to afford a home and heat it. To be able to have food on the table and not face huge debt when gaining a university education. Nothing horrendous about any of those ‘pretensions’.

Unfortunately, the Brexiteers were sold a pig in a poke and the entire country will be massively worse off with leave. The most recent analysis suggests by 9o billion. Any politician who wants to put the interests of their citizens first would say, hold on a minute, let’s not shoot ourselves in the foot, chasing the slimy dreams of snakeoil salesmen and disaster capitalists.

Sorry, but you have no concept of the big picture. No doubt you stick your fingers in your ears and scream ‘project fear’ at any rational analysis of the disaster that will be a no deal Brexit.

Technically, Labour’s position is to leave the EU and to join “A” Customs Union (not to be confused with “THE” Customs Union). Leaving aside the fact that tariff free trade in goods is incompatible with unrestricted State support of industry, Labour’s position would enjoy majority support both in Parliament (if they ever stopped playing silly games) and with the electorate. When Parliament took control of the Order Paper and allowed a series of indicative votes on available options, Labour’s position fell short by three votes. The SNP (35 votes) abstained over some petty distinction (they proposed to join “THE” Customs Union).

Labour under Corbyn have however been denied the opportunity to take Downing Street as part of an anti-Brexit, unity government due to the drooling stupidity of Swinson.

England and Wales in “A” Customs Union while Scotland and NI transferred to “THE” Customs Union may have been a best fit solution but we’ll probably never know.

Genius has its limitations stupidly is not thus encumbered.

Very well written responce for a person trying to make out that they are from the left of politics but a true believer in government of the rich, by the rich and for the rich.

Corbyn is all soft-hands and whatever spine he had, he traded for playing nice with the Blairites. Rather than risk civil war in Labour, Corbyn has allowed the tail to wag the dog. Tony Blair is a truly a wicked and vile schemer.