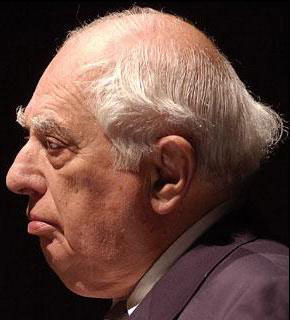

Bernard Lewis, seen by some in the West as a giant of Arab and Muslim scholarship, left behind a legacy of falsehoods and politically-motivated distortions, as As’ad AbuKhalil explains.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

There is no question that Bernard Lewis was one of the most politically—not academically—influential Orientalists in modern times.

There is no question that Bernard Lewis was one of the most politically—not academically—influential Orientalists in modern times.

Lewis’ career can be roughly divided into two phases: the British phase, when he was a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and the second phase, which began in 1974, when he moved to Princeton University and lasted until his death on May 19. His first phase was less overtly political, although the Israeli occupation army translated and published one of his books, and Gold Meir assigned articles by Lewis to her cabinet members.

Lewis knew where he stood politically but he only became a political activist in the second phase. His academic production in the first phase was rather historical (dealing with his own specialty and training) and his books were then thoroughly documented. The production of his second phase was political in nature and lacked solid documentation and citations.

In the second phase, Lewis wrote about topics (such as the contemporary Arab world) on which he was rather ignorant. The writings of his second phase were motivated by his political advocacy, while the writings of the first phase was a combination of his political biases and his academic interests.

Shortly upon moving into the U.S., Lewis met with Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, the dean of ardent Zionists in the U.S. Congress. He thus started his political career and his advocacy, which was often thinly hidden behind the titles of superficial books on the modern Arab world. Lewis not only mentored various neoconservatives, but he also elevated the status of Middle East natives that he approved of. For instance, he was behind the promotion of Fouad Ajami (he dedicated one of this books to him), just as he was behind introducing Ahmad Chalabi to the political elite in DC.

Furthermore, Lewis was also behind the invitation of Syrian academic Sadiq Al-Azm to Princeton in the early 1990s (as Edward Said told me at the time) because Lewis always relished Al-Azm’s critique of Said’s Orientalism. Sep. 11 only elevated the status of Lewis and brought him close to the centers of power: he advised George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and other senior members of the administration.

In the lead-up to the Iraq war, he assured Cheney (relying on the authority of Ajami) that not only Iraqis, but all Arabs, would joyously greet invading American troops. And he argued to Cheney before the war, using the dreaded Zionist and colonial cliché, that Arabs only understand the language of force. (Lewis would later distort his own history and claim that he was not a champion of the Iraq invasion although the record is clear).

Lewis was not only close to the higher echelons of the U.S. government, but in addition to his long-standing ties to Israeli leaders, he was close to Jordanian King Husayn and his brother, Hasan (although Lewis would mock what he considered a Jordanian habit of eating without forks and knives, as he wrote in Notes on a Century: Reflections of a Middle East Historian, on page 217).

Lewis was also close to the Shah’s government, and to the military dictatorship in Turkey in the 1980s. Kenan Evren, the Turkish general who led the 1980 military coup, had a tete-a-tete with Lewis during one of his visits to D.C. Lewis had contacts with the Sadat government, and Sadat’s spokesperson, Tahasin Bashir, in 1971 sent a message through Lewis to the Israeli government regarding Sadat’s interest in peace between the two countries.

Distorted View of Islam

There are many features of Lewis’s works, but foremost is what French historian Maxime Rodinson called “theologocentrism”, or the Western school of thought which attribute all observable phenomena among Muslims to matters of Islamic theology.

For Lewis, Islam is the only tool which can explain the odd political behavior of Arabs and Muslims. Lewis used Islam to refer not only to religion, but also the collection of Muslim people, governments ruling in the name of Islam, Shari`ah, Islamic civilization, languages spoken by Muslims, geographic areas in which Muslims predominate, and Arab governments. A review of his titles show his fixation with Islam. But what does it mean for Lewis to refer to Islam as being “the whole of life” for Muslims, as he does in Islam and the West?

Lewis also began the trendy Islamophobic, Western obsession with Shari`ah when he wrote years ago in the same book that for Muslims religion is “inconceivable without Islamic law.” There are hundreds of millions of Muslims in the world who live under governments which don’t subscribe to Shari`ah. No Muslim, for example, questions the Islamic credentials of Muslims who live in Western countries under secular law. Lewis even notes this fact, but it confuses him. In Islam and the West he states in bewilderment: “There is no [legal] precedent in Islamic history, no previous discussion in Islamic legal literature.”

Lewis could have benefited from reading James Piscatori’s book, Islam in a World of Nation States, which shows that Shari`ah is not the only source of laws even in countries where Islam is supposedly the only source of law. But Lewis was stuck in the past, he could only interpret the present through references to the original works of classical Islam.

His hostility and contempt for Arabs and Muslims was revealed in his writings even during the British phase of his career, when he was politically more restrained. He was influenced by the idea of his mentor, Scottish historian Hamilton Gibb, regarding what they both called “the atomism” of the Arab mind. The evidence for their theory is that the classical Arabic poem of Jahiliyyah and early Islam was not organically and thematically unified, but that each line of poetry was independent of the other.

I remember back in 1993 when I discussed the matter with Muhsin Mahdi, a professor of Islamic philosophy at Harvard University, when I was reading the private papers of Gibb at the Widener Library. Mahdi said that their ideas are completely out of date and that recent scholarship about the classical Arabic poem refuted that thesis. (Lewis would resurrect the notion about the “atomism” of the Arab mind in his later Islam and the West).

Other writings of Lewis became obsolete academically. In his The Muslim Discovery of Europe he recycles the view that Muslims had no curiosity about the West because it was the land of infidelity and that they suffered from a superiority complex. A series of new scholarly books have undermined this thesis by Lewis largely by scholars looking into Indian and Iranian archives. The Palestinian academic, Nabil Mater, in his books Britain and the Islamic World, 1558-1713, Europe Through Arab Eyes, 1578-1727, and Turks, Moors and Englishmen in the Age of Discovery, paints a very different—and far more documented—picture of the subject that Lewis spent a career distorting.

Relished in Disparaging Arabs

In addition, the tone of Lewis’ writings on Arabs and Muslims was often sarcastic and contemptuous. Lewis did the work of the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), which was started in 1998 by a former Israeli intelligence agent and an Israeli political scientist, before MEMRI existed: he relished finding outlandish views of individual Muslims and popularizing them to stereotype all Arabs and all Muslims.

In the early editions of Arabs in History, Lewis remarked that none of the philosophers of the Arab/Islamic civilization were Arab in ethnic extraction (except Al-Kindi). What was Lewis’s point except to denigrate the Arab character and even genetic makeup? In the same book he cites an Ismaili document but then quickly adds that it “is probably not genuine.” But if it is “probably not genuine” why bother to cite it except for his fondness for bizarre tidbits about Arabs and Muslims?

The Orientalism of Lewis was not representative of classical Orientalism with all its flaws and shortcomings and political biases. His harbored more of an ideology of hostility against Arabs and Muslims. This ideology shares features with anti-Semitism, namely that the whole (Muslims in this case) form a monolithic group and that they pose a civilizational danger to the world, or are plotting to take it over, and that the behavior or testimony of one represents the total group (Islamic Ummah).

In writing about contemporary Islam, Lewis spent years recycling his 1976 Commentary magazine article titled, “The Return of Islam.” What he doesn’t answer is, “return” from where? Where was Islam prior? In this article, Lewis exhibits his adherence to the most discredited forms of classical Orientalist dogmas by invoking such terms as “the modern Western mind.” He thereby resurrected the idea of epistemological distinctions between “our” mind and “theirs”, as articulated by the 1976 racist book, The Arab Mind by Israeli anthropologist, Raphael Patai. (This last book would witness a resurrection in U.S. military indoctrination after Sep. 11, as Seymour Hersh reported).

An Obsession with Etymology

For Lewis, the Muslim mind never seems to change. Every Muslim, regardless of geography or time, is representative of any or all Muslims. Thus, a quotation from an obscure medieval source is sufficient to explain present-day behavior. Lewis even traces Yaser Arafat’s nom de guerre (Abu `Ammar) to early Islamic history and to the names of the Prophet Muhammad’s companions, though `Arafat himself had explained that the name derives from the root `amr (a reference to `Arafat’s construction work in Kuwait prior to his ascension to the leadership of the PLO).

Because `Arafat literally embraced Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran when he first met him, Lewis finds evidence of a universal Muslim bond in the picture. But when Lewis revised his book years later, he took note in passing of the deep rift which later developed between `Arafat and Khomeini and said simply: “later they parted company.” So much for the theory of the Islamic bond between them. Lewis must not have heard of wars among Muslims, like the Iran-Iraq war.

Lewis read the book Philosophy of Revolution by the foremost political champion of Arab nationalism, Nasser of Egypt, as containing Islamic themes. He must have been the only reader to come to that conclusion.

Another feature in Lewis’s writings is his obsession with etymology. To compensate for his ignorance of modern Arab reality, Lewis would often return to the etymology of political terms among Muslims. His book, The Political Language of Islam, which is probably his worst book, is an example of his attempt to Islamize and standardize the political behavior of all Muslims. His conclusions from his etymological endeavors are often comical: he assumes that freedom is alien to the Arabs because the historical meaning of the word in an ancient Arabic dictionary merely connoted the absence of slavery. This is like assuming that a Westerner never engaged in sex before the word was popularized. He complains that some contemporary political terms, like dawlah (state), lost some of their original meanings, as if this is a problem peculiar to the Arabic language.

In his early years, Lewis was close to the classical Orientalists: he wrote in a beautiful style and his erudition and language skills showed through the pages. His early works were fun to read, while his later works were dreary and dull. But Lewis was unlike those few classical Orientalists who managed to mix knowledge about history of the Middle East and Islam with knowledge of the contemporary Arab world (scholars like Rodinson, Philip Hitti and Jacques Berque). Lewis’s ignorance about the contemporary Arab world was especially evident in his production during the U.S. phase of his long career. His book on the The Emergence of Modern Turkey, which was one of the first to rely on the Ottoman archives, was probably one of his best books. There is real scholarship in the book, unlike many of his later observational and impressionable works.

In his later best-selling books, What Went Wrong? and The Crisis of Islam, one reads the same passages and anecdotes twice. Lewis, for example, relishes recounting that syphilis was imported into the Middle East from the new world. His discussion of Napoleon in Egypt appears in both books, almost verbatim. The second book contains calls for (mostly military) action. In The Crisis of Islam, Lewis asserts: “The West must defend itself by whatever means.” The book reveals a lot about his outlook of hostility towards Muslims.

Misunderstood Bin Laden

One is astonished to read some of his observations on Muslim and Arab sentiments and opinions. He is deeply convinced that Muslims are “pained” by the absence of the caliphate, as if this constitutes a serious demand or goal even for Muslim fundamentalist organizations. One never see crowds of Muslims in the streets of Cairo or Islamabad calling for the restoration of the caliphate as a pressing need.

But then again: this is the man who treated Usamah Bin Laden as some kind of influential Muslim theologian who is followed by world Muslims. Lewis does not treat Bin Laden as the terrorist fanatic that he is, but as some kind of al-Ghazzali, in the tradition of classical Islamic theologians. Furthermore, Lewis insists that terrorism by individual Muslims should be considered Islamic terrorism, while terrorism by individual Jews or Christians is never considered Jewish or Christian terrorism.

In his retirement years, his disdain for the Palestinian people became unmasked. Although in his book The Crisis of Islam he lists acts of violence by PLO groups—only ones, curiously, that are not directed against Israeli occupation soldiers. He lists not one act of Israeli violence against Palestinians and Arabs. To discredit the Palestinian national movement, he finds it necessary to tell yet again the story of Hajj Amin Al-Husayni’s visit to Nazi Germany, apparently seeking to stigmatize all Palestinians.

He is so disdainful of the Palestinians that he finds their opposition to Britain during the mandate period inexplicable because he believes that Britain was, alas, opposed to Zionism. Lewis is so insistent in attributing Arab popular antipathy to the U.S. to Nazi influence and inspiration that he actually maintains that Arabs obtained their hostility to the U.S. from reading the likes of Otto Spengler, Friederich Georg Junger, and Martin Heidegger. But when did the Arabs find time to read those books when all they read were their holy book and Islamic religious texts—as one surmises from reading Lewis?

While he displays deep–albeit selective–knowledge when he talks about the Islamic past (where his documentation is usually thorough), his analysis is quite simplistic and superficial when addressing the present (where he often disregards documentation altogether). For instance, he sometimes produces quotations without endnotes to source them: In Islam and the West he quotes an unnamed Muslim calling for the right of Muslims to “practice polygamy under Christian rule.” In another instance, he debates what he considers to be a common Muslim anti-Orientalist viewpoint, and the endnotes refer only to a letter to the editor in The New York Times.

Lewis once began a discussion by saying: “Recently I came across an article in a Kuwaiti newspaper discussing a Western historian,” without referring the reader to the name of the newspaper or the author. He also tells the story of an anti-Coptic rumor in Egypt in 1973 without telling the reader how he collects his rumors from the region. On another page, he identifies a source thus: “a young man in a shop where I went to make a purchase.”

Lewis was not shy about his biases in the British phase of his career, but be became an unabashed racist in his later years. In Notes on a Century, he did not mind citing approvingly the opinion of a friend who compared Arabs to “neurotic children”, unlike Israelis who are “rational adults.” And his knowledge of Arabs seems to decrease over time: he would frequently tell (unfunny) jokes related to Arabs and then add that jokes are the only indicator of Arab public opinion because he did not seem to know about public opinion surveys of Arabs. He also informs his readers that “chairs are not part of Middle Eastern tradition or culture.” He showers praise on his friend, Teddy Kollek (former occupation mayor of Jerusalem) because he set up a “refreshment counter” for Christians one day.

The political influence of Lewis, who lent Samuel Huntington his term, if not the theme, of “the clash of civilization”, has been significant. But it would be inaccurate to maintain that he was a policy maker. In the East and the West, rulers rely on the opinions and writings of intellectuals when they find that this reliance is useful for their propaganda purposes. Lewis and his books were timely when the U.S. was preparing to invade Muslim countries. But the legacy of Lewis won’t survive future scholarly scrutiny: his writings will increasingly lose their academic relevance and will be cited as examples of Orientalist overreach.

Readers who would like more specific sourcing from Lewis’s books can contact the author at AAbukhalil@csustan.edu

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam & America’s New ‘War on Terrorism’ (2002), and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He also runs the popular blog The Angry Arab News Service.

If you enjoyed this original article please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

A nice summary from 3 decaded ago of those following the trail blazed by Lewis in fanning the flames of fear and loathing of Arabs in general and Palestinians in particular (“the most hated people by the West” per Jean Genet, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/jun/05/jean-genet-hero-ahdaf-soueif )

https://zcomm.org/wp-content/uploads/zbooks/www/chomsky/ni/ni-c10-s19.html

Incidentally, the beloved Professor who wrote about the “breeding and bleeding” untermenschen was awarded a National Prize in a glittering ceremony at the White House celebrating her humane scholarship:

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2007/11/white-house-awards-pipes-and-wisse-humanities-medals

Edward Said on Lewis:

“Lewis is an interesting case to examine because his standing in the political world of the Anglo-American Middle Eastern Establishment is that of the learned Orientalist, and everything he writes is steeped in the ‘authority’ of the field. Yet for at least a decade and a half his work in the main has been aggressively ideological, despite his various attempts at subtlety and irony. I mention his recent writing as a perfect exemplification of the academic whose work purports to be liberal objective scholarship but is in reality very close to being propaganda AGAINST his subject material. But this should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with the history of Orientalism; it is only the latest – and in the West, the most uncriticised – of the scandals of ‘scholarship.'” (Orientalism, 1978, Page 316)

Also see: https://mondediplo.com/2005/08/16lewis

August 2005 – Malevolent fantasy of Islam by Alain Gresh

EXCERPT:

“Under the Bush presidency, Lewis has become a valued US adviser. He is close to the neoconservatives, particularly Paul Wolfowitz who in 2002, as deputy defence secretary, paid this tribute at a ceremony held in Lewis’s honour in Tel Aviv: “Bernard Lewis has brilliantly placed the relationships and the issues of the Middle East into their larger context, with truly objective, original, and always independent, thought. Bernard has taught [us] how to understand the complex and important history of the Middle East and use it to guide us where to go next to build a better world for generations.” In 2003 Lewis encouraged the US administration to take the next step in Iraq. He prophesied that the invasion would lead to a new dawn, that US troops would be greeted as liberators, and that the Iraqi National Congress under his friend Ahmad Chalabi, a shady exile with no real influence, would rebuild a new Iraq.”

Bernard Lewis – BORN 31 May 1916 – DIED 19 May 2018 – 101 years old.

It behoove one to maintain the status quo & so the bend & twist the truth every which way to make it fir desired outcomes.

Yet another Organ Grinder’s Monkey passes into obn security.

RIP for the damage that you may have incurred in your zeal to be loved.

Sounds like a horse’s ass. But those who he taught are the leaders in our government.

People like Bernard Lewis are useful in justifying actions by demonizing the enemy. It makes it more respectable. He was useful when a little intellectual garbage was needed to assure thoughtful persons who might have doubts that it really is ok to kill Arabs. They are bad people and good riddance. That the Professor, according to the author, seemed to be a willing participant in the killing process makes him a candidate for fantasy war crimes. Brings to mind Judgement at Nuremberg.

Bernard Lewis concludes as follows in his book ISLAM: THE RELIGION AND THE PEOPLE referenced in Wikipedia under the heading “views and influence on contemporary politics:Jihad”:

“Muslim fighters are commanded not to kill women, children, or the aged unless they attack first; not to torture or otherwise ill-treat prisoners; to give fair warning of the opening of hostilities or their resumption after a truce; and to honor agreements. ….. At no time did the classical jurists offer any approval or legitimacy to what we nowadays call terrorism. Nor indeed is there any evidence of the use of terrorism as it is practiced nowadays.”

In Lewis’ view, the “by now widespread terrorism practice of suicide bombing is a development of the 20th century” with “no antecedents in Islamic history, and no justification in terms of Islamic theology, law, or tradition.” He further comments that “the fanatical warrior offering his victims the choice of the Koran or the sword is not only untrue, it is impossible” and that “generally speaking, Muslim tolerance of unbelievers was far better than anything available in Christendom, until the rise of secularism in the 17th century.”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Lewis

As`ad AbuKhalil neglects to mention that Lewis was also an Armenian genocide denier, for which he was convicted by a French court and fined a symbolic 1 franc:

https://anca.org/press-release/armenian-genocide-denier-bernard-lewisawarded-national-humanities-medal/

Unsurprisingly, Lewis is hated by Armenians:

http://www.armeniapedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Lewis

Lewis’ denial of the Armenian genocide stems from the same profound character flaw as does his Islamophobia – an identification with one group (in this case Turkey) which led him to deny the reality of profound injustices which that group had committed.

Here Lewis may have been correct. There is zero historical evidence of a “genocide” of Armenians. This is Western and Armenian political propaganda to demonize Turks (not very different from the sort you see and hear today to demonize Arabs). It started in earnest in the 1960s claiming 1 million massacred Armenians, and the founding of the terrorist group ASALA. It evolved to claim 1.5, then 2 million Armenian dead (interesting how Armenians keep “dying” long after the “genocide”). Given that we can’t even agree on the numbers of Iraqis or Syrians who have died in recent wars, it is remarkable that we can agree on the number of Armenians who died in 1915.

the other problem, of course, is that all of these Armenians were “massacred”. That massacres occured is a given, but most of the 600,000 or so Armenians who did die, most likely did so from hunger and disease, just like the Ottoman troops and Muslim civilians in Anatolia at the time.

Though the Turks have requested, both before and after Erdo?an, to set up a historical committee of Armenian, Turkish and other eminent historians to investigate the tragedy that occured in Anatolia during WWI, the Armenians have refused. Like many Western political actors today, they believe that they only have to make a claim for that claim to be valid. Claims of atrocities, real, exaggerated or imagined are not “genocide”. Reporting only one side of the story, as many Armenian “historians” do is not history. That Westerners read this and belive this, is not surprising. Most do today when the other is targeted.

Lewis was certainly an orientalist, but that doesn’t mean he was always wrong, even when biased.

“Lewis may have been correct. There is zero historical evidence of a “genocide” of Armenians”

No, the evidence for the Armenian genocide is irrefutable. In fact, Raphael Lemkin, who invented the legal concept of ‘genocide’ used the Armenian genocide as his prime exemplar:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raphael_Lemkin#Influence_of_the_Armenian_Genocide

As the influence of extreme mono-ethnicising Ataturkism progressively wanes in Turkey, more and more Turkish citizens (ethnic Turks and others) are speaking openly about their own remorse over the Armenian genocide:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Apologize_campaign

http://www.ozurdiliyoruz.info/index.html

http://www.ozurdiliyoruz.info/foreign.aspx

I hope that one day the United States will issue an official apology for the genocide of the Native Americans.

James you are not alone on the hope for American Indians and their overly well deserved apology. It would be a start if the apology were sincere. I won’t even suggest the negatives that come with this hope I have, because I am the consistent dreamer of a better America to come.

They say, by the year 2042 America will not longer be a nation of majority White. If this prediction is correct, then that would mean America would become a nation composed of minority’s. If I’m missing something here then please correct me, but with the ever changing tide of evolution from one generation to the next, it would only then seem reasonable to assume that by the year 2042 America may mature through this ethnic process to overcome much of its prejudices, as this change could demand a righteous confession for many of our past U.S. crimes. Crimes like wars brought on by false flags. Crimes like assassination, and their coverups.

Yes, I’m a dreamer, and much of what we see on the horizon could change course within an instant if the politics so sway, but one can have hope, and sometimes hope although often naive is a worthwhile thing to hang your hat on. Joe

I have a scant familiarity with Bernard Lewis. Once I perused one of his books, I guess “What went wrong”, in my local bookstore, and what floored me were his complaints about Muslim taste in music. Strangely enough, he did not complain about food — because Israelis adopted a lot of it? But popular “folk music” of Israeli Jews is not all that different from Arabic. This suggested the mode of thinking: I do not like them, they like or use X, so X is vile. There is a myriad of examples, a recent one is that “dumb weapons” are inherently immoral because they produce un-intended victims, Russian “dumb bombs” indicate Russian moral degeneracy, but most morally horrible are Syrian barrel bombs. Nothing like smart bombs and missiles that can accurately massacre a wedding or a funeral.

However, I still do not quite understand the deranged ideological construct that Muslim/Arab are inferior in assorted way so the West should behave firmly AND institute democracy, WITH the help of Western friends among absolute monarchies in the Gulf. This is logically inconsistent, and, surprise!!?? did not work. And BL joined that deranged crowd. After 75 mental faculties may be less sharp so he personally has some excuse, but how that b…t could convince so many old and young? I guess so-called rationalism of the West is less rational than some believe — irrationally.

I read Lewis’, “What Went Wrong”, soon after it came out after 9-11.

I was amazed by his conclusion in the book that the Muslim world did not adopt to modernity because there were no public clocks in the cities and towns that he had supposedly observed.

I have no idea how he came to conclude such a ridiculous concept. I remember thinking that maybe Muslims just wanted a more relaxing lifestyle…

I have a Swiss colleague, and I live in a small college town (university is big, 50% of the population). He was surprised that every clock in town showed a different hour. Definitely, timeliness in USA is much inferior to Switzerland, but the Swiss are too politite to harp about American inferiority. But this was long time ago, now rich and poor, Muslim, Hindu, Christian etc., all check time on their cell phones, and it is accurate. Apparently, even poor farmhands in developing countries must have cell phones.

That said, NYT had an article about percentage of trains delayed for more than 15 minutes in metropolitan subway systems. Mexico City was number one, something like 50%, and NYC was right behind. Moscow was not included, but a Russian article claimed that this percentage is 5 times lower than in Paris, where it is 1%. Perhaps Lewis had a point and USA is abandoning modernity.

As I read this article concerning Bernard Lewis all I could think of, was how well a propagandist can do distributing hate and still be considered an intellectual. But then I remembered we have a lot of corrupt thugs passing themselves off as senators and representatives, and why even some of these imposters are in the White House. So once again I turn out my night light knowing that not much has changed from yesterday.

Bernard Lewis was just one of the “specially chosen” Zionist Jewish intelectuals & well known “expert” on the Middle East to spend valuable time in the White House explaining to President G.W.Bush why he just had to invade Iraq.

His promotion of the struggle between the West & Islam is well known as was his introduction of terms such as “Islamic fundamentalism” & the phrase “clash of civilizations”.

Apparently he played the White House “like a violin” having meetings with Cheney & Rumsfeld assuring them that American troops would be welcomed by Iraqis and Arabs, relying on the opinion of his colleague Fouad Ajami…

Jacob Weisberg even described Lewis as “perhaps the most significant intellectual influence behind the invasion of Iraq”.

…

Lewis was what in Ireland is called a “merchant of hate”.

http://www.twf.org/News/Y2003/0629-Bernard.html

Edward Said wrote a memorable essay entitled “Conspiracy of Praise” on abysmal level of scholarship on the Middle East:

https://www.merip.org/mer/mer136/conspiracy-praise

Another gem on the “Arab Mind” that was handed out to American soldiers deployed in Iraq:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/may/24/worlddispatch.usa

Zionists have to be congratulated in their successful promotion of Islamophobia .

Raphael Patai – born Ervin Gyorgy Patai (in Budapest, Hungary, in 1910 was the son of well known Zionist Joszef Patai who wrote a number of books promoting Zionism.

Raphael Patai moved to Jerusalem (1933 –1947) & still maintained that there would be peaceful outcome to the Zionist “struggle” even as Jewish terrorism was at its height & stating that

Arabs “hate” the west.

He became a Rabi & together with Bernard Lewis became one of the most respected Jewish scholars of the twentieth century.

Somehow their writings were used to lead the USA into its terrible carnage & destruction of the Middle East

> Edward Said wrote a memorable essay entitled “Conspiracy of Praise” on abysmal level of scholarship

> on the Middle East:

I speak here less as a Palestinian who wants to keep saying “but we exist and always have and will,”

Or, as Haim Hanegbi put in in the film The Common State,

“Israel has three fundamental problems:

– there were Palestinians

– there are Palestinians, and

– there will be Palestinians.”

When he moved to the US, Lewis returned to his roots. His early work on the Ottomans is excellent, but it was abandoned. Whether or not there was pressure, he gave in easily. I was recently asked to review a manuscript by a scholar in a similar situation. This scholar’s early work on Early Islamic history was excellent, but then he got a professorship, and it all stopped. The manuscript can only be described as sub-Lewisian. I was obliged to submit a critical report, and to refuse the honorarium. When I looked at what the publishing house does, I could see that I was not likely to receive much sympathy from them.

“his work on Ottomans is excellent” …. hardly, he was a Genocide denier. who will you praise next David Irving, holocaust denier?

Said’s “Orientalism” has some good criticisms of Lewis.

Oligarchy enshrines fake scholars of the tribe in think tanks, and uses its mass media to make them seem widely accepted. The z-word pseudo-scholar Lewis exemplifies the corruption and abuse of scholarship as propaganda. Scholarly credentials, style, and erudition disguise primitive errors of reasoning. The targeted group is claimed to be no more than its most extreme actors or ideology, but not the favored group. Selected facts are substituted for history, and selected views are presented as “our” mind versus “theirs” for indoctrination.

“Scholarly credentials, style, and erudition disguise primitive errors of reasoning,” similar to Chomsky-hating William Buckley Jr..

Yes, Buckley is the star of fake scholars, and debaters, as his shows trapped the opponent alone, while he had his debate team and controlled the questions.

Neither the intellectually dishonest Lewis nor the opportunistic warmonger Krauthammer can be unlinked from the horrors of the illegal Iraq war and the mass slaughter in Libya and Syria.

They both were the active promoters of the slaughter, motivated by their tribal-supremacist beliefs. Their legacy is the tremendous harm inflicted towards the important achievements of western civilization.

Looks like Lewis citing (“one man told me”) was the same as Solgenitzyn’s – his propaganda books is chock full of such “sources”.

Could you explain to the reader why Lewis’ opuses have been published and promoted in the UK and the US, whereas Solgenitzyn’s documentary “Two Hundred Years Together” — based on the archival materials — has been sequestered by all publishing houses in the US and the UK?

Let me guess, you wholeheartedly support the sequestration because of some very inconvenient truths that are not in accord with Lewis’ selectivity: “he [Lewis] lists not one act of Israeli violence against Palestinians and Arabs.”

When Solgenitzyn’s documentary is finally available to the readers in the US and the UK, then you could come with your critique. Before that, your opinion smacks of slander.

“Two Hundred Years Together is a two-volume historical essay by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. It was written as a comprehensive history of Jews in the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and modern Russia between the years 1795 and 1995.”

Progressives have identified Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s service to the powerful. I don’t remember the details, but I have been alerted.

lidia, perhaps you don’t know but Sozhenitzen was a novelist, not a historian. His novels described the horrors of the Stalin years. He was one of the victims and wrote down his experiences as fiction. Lewis presented himself as an objective historian and as Abu Kahlil explains he was not — just another hack for western imperialism.

Good article! Though I’m not familiar with the writings of Bernard Lewis (I read very few conservatively written articles/books, since they start from a political viewpoint with which I am essentially diametrically opposed), from the above article it certainly sounds like he was prone to generalizing across whole geographic regions and political/religious groups, often from one or two anecdotal examples. For all but the most superfluous cultural traits (dress, language, food, etc), this is VERY ‘sketchy’ thing to do, logically and academically speaking. Just think of picking 3 or 4 people at random in THIS country — would you want to predict what their TRUE cultural/political/religious views are based on the fact that they’re US citizens? Even going to older civilizations in the Orient where some of these things have stabilized and solidified due to time, and there’s supposedly a more ‘monolithic’ culture, I still believe it would be hard to generalize about 10 citizens of China or India, much less 1+ BILLION Chinese or Indian people. Similarly, to say that ‘Muslims’ or ‘Christians’ or ‘Jews’ or ‘Hindus’ uniformly believe in certain political ideas simply because the PROFESS to believe in certain religious ideas, certainly seems to be a stretch.

For good or bad, the world is a very complex place, and to try to reduce these complexities is a natural human trait — we want to get our minds ‘around’ it and understand it. But intellectually speaking, to try to gain a VALID, relatively objective understanding of the world, one has to fight the impulse to casually generalize across large groups without a lot of strong, credible data to support it. Personally, when I hear people generalize like this, I tend to believe they’re being intellectually lazy and not really interested in understanding another culture/country/religion/etc beyond a ‘sound-bite’ or meme, or they have a political agenda they’re trying to promote, tacitly or overtly.

“the tone of Lewis’ writings on Arabs and Muslims was often sarcastic and contemptuous.”

I stopped reading this article at this point as I lost interest in Lewis. If this is true, then all of Lewis’ writing about “Islamic” people is not to be trusted and may even be said to be in strongly in behalf of evil. The first thing in scholarship is respect for the subject of that scholarship. In a way, I am glad Lewis is so openly contemptuous because you know what he says is twisted, unlike other Western “scholars” who hide their hate for non-Western peoples under “dispassionate” masks.

As an American I am proud that we have a First Amendment, the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln, FDR and so on. But I also hate the fact that we have American “exceptionalism” as it gives us the right to look down on other people, cheat them, lie to them, kill them indiscriminately with drones, and invade their countries. I do know that so many other countries have the same problem but as an American I am ashamed of that thing in America, and one thing that would help the best in ourselves, is to criticize instead of praising, the work of anyone such as Lewis who encourages us to have even more contempt for other nations and peoples.

“I stopped reading this article at this point as I lost interest in Lewis.” I understand the sentiment. Who has the time?, as well. One must prioritize. And yet, I take the point that his writing has been influential. Actually, I think the point was, to be more accurate, that he and his ‘scholarly’ work were useful – the US ruling class. For that reason, I read the entire article. Re-consider. It’s not that long.

This was actually scary. It is a true statement of fact that Islam was founded in what is today Saudi Arabia by a man who was an Arab. But Islam isn’t an Arab religion any more than Christianity is a Jewish (not in the religious sense) religion. Most of N. Africa is Muslim (as well as much else of Africa) yet they are not Arab. Iranians are Muslim and they are Persians and NOT Arabs (as they will tell you in no uncertain terms). From Iran, where do you want to go? Afghanistan, the southern, central Asian istans, Pakistan, the Muslims of the Philippine Islands and other islands of the area. None of these guys are Arab. And their politics aren’t going to have much to do with the loony-bins of the classic Middle East. To suggest that they are all the same or even vaguely similar by virtue of having the same religion makes about as much sense as saying that the earth is the center of the solar system.

I agree with your general point but when you say that the politics of non-Arab Muslims “aren’t going to have much to do with the loony-bins of the classic Middle East” you imply a type of Orientalism in which the Middle East is this barbaric and savage region where the tribes are always at war with each other and sectarian conflict is just something built into the DNA of the Arab. Of course this is racist nonsense: fundamentalist Islam exists wherever there are Muslims – ISIS or similar groups are in Africa and Southeast Asia as well, Boko Haram in Africa, Russian and Chinese and British ISIS soldiers in Syria, etc. And “extreme” or “fundamentalist” ideology in general is of course common to all humans, not to any specific race, religion, region, or population; there is something quite extreme and fundamentalist about 500 years of Western imperialism continuting today in the form of US Empire which believes itself to have an inherent right to the Earth’s natural resources.

Thanks to the Angry Arab for another edifying article on a subject I knew nothing about.

I did not intend to imply the Middle East (which ends at Persia, by the way) was a barbaric and savage region where the tribes are always at war. Make no mistake. The Middle East and South Asia is tribal, not nation-state, land and their problems have two sources: Israel and the US.

You also need to separate politics from religion. It is a true statement of fact that the Middle Eastern religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all tend to want to control a person’s entire life but major percentages of the adherents of those religions have been able to have a life separate from religion. Which is important because you have to have time to worry about where the school system is setting the school boundaries, and when the pot holes are going to get filled, and if your boss is going to give you a raise. And you are right the fundamentalists are the real problem. All religions have them and the three under discussion here are the biggest pain in the ass. If we could collect all the Wahhabi’s (Islam, Saudi Arabia), Zionists (Judaism, Israel), and evangelical Christians (Christians, Mostly it seems in the US) and ship them off to their own little country on the dark side of the moon, the world would be a happier place.

You did not mention Indonesia, where nearly every one of its many millions of inhabitants is Muslim and none are Arabs.

The defining characteristic of an Arab is that his or her first language is Arabic. Hence, those living in the Maghreb (with the exception of the Berbers) and eastward to Iraq are Arabs.