Exclusive: The myth that bad intelligence led to the Iraq War won’t die, but the evidence is clear that President George W. Bush decided to invade after 9/11, though Iraq had nothing to do with it, and intel was assembled to sell the invasion to a scared U.S. public, as ex-CIA analyst Melvin A. Goodman explains.

By Melvin A. Goodman

Last Sunday, the Washington Post, which itself shares blame for the disastrous Iraq War, used the memoirs of President George W. Bush and other key members of his administration to let those principals express their self-serving views about how specious intelligence had led them to a decision to invade Iraq a decade ago. In their books, they opportunistically portray themselves as misled by bad intel, just like everyone else.

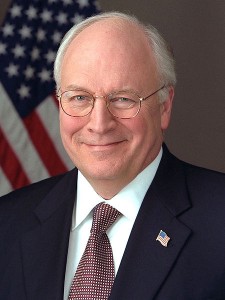

Yet, since the war was, in reality, a deadly undertaking paved by lies and deceit at all levels, it would have been far more useful for the Post’s Feb. 3 retrospective to try to glean from the memoirs the real reasons for the use of force against Saddam Hussein in 2003. To be fair to the Post, the memoirs by President Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice did not provide much insight; they were noteworthy for being hopelessly unapologetic about their decision to go to war, their conduct of the war, and their handling of the post-invasion situation.

Further, the memoirs provided little sense of the true inside-the-White-House back story, the strategic reasoning behind the urgency of a preemptive war against Iraq, though the participants still claim that the war was “worth the costs.” What self-reflection there is about the prosecution of the war comes mostly in the form of finger-pointing.

Indeed, the memoirs of Cheney, Rumsfeld and Rice were surprising in their direct criticisms of President Bush, a break with tradition from the memoirs of high-ranking principals from other administrations who generally shield their presidents from criticism even while score-settling with rivals.

In the memoirs from the Bush years, the high-level principals express fondness for the President but fault him for management failures such as allowing too many hands on the policy steering wheel. Rumsfeld described National Security Council (NSC) meetings that ended without precise objectives for the way ahead, even with Bush presiding. Cheney and Rice cite the President’s inability to clearly or firmly resolve key differences within the NSC, which only the President could do.

In their memoirs, Cheney and Rumsfeld particularly eviscerate Powell and Rice for their roles in the Iraq debacle. Cheney is critical of the State Department for failing to conduct post-war planning, although State’s efforts were undercut by the fact that Rumsfeld forbade his subordinates from taking part in inter-agency meetings on the future of Iraq.

Rumsfeld blames Powell for using his State Department deputy, Richard Armitage, to attack the Defense Department; Powell blames Rumsfeld for using his Defense Department deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, to attack the State Department. Cheney and Rumsfeld cite Rice’s failure to resolve differences within the policy community and to present President Bush with clear choices.

Cheney also puffs up his role in framing the policy choices for President Bush (the self-proclaimed “Decider”), noting that he (Cheney) received the CIA briefings before the President. That was why high-level CIA officials referred to Cheney as “Edgar” (i.e., Edgar Bergen, the puppet master for the dummy Charlie McCarthy, with Bush playing the dummy in this metaphor).

Some policymakers favored ousting Hussein, followed by a quick handover to the Iraqis, while others wanted a long-term nation-building project. Only after the start of the war did President Bush name Paul Bremer to head the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance and manage the transition in Iraq during the post-invasion phase. Cheney, Rumsfeld and Rice blame Bremer for botching the occupation and blame Bush for enabling Bremer to ignore the chain of command and “pick and choose” his subordinates. Bremer’s decision-making was opaque, even to the secretaries of state and defense.

But the Washington Post should not have relied on these memoirs to explain any aspect of the war because of the key issues that Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld and Rice do not address. For instance, there is no explanation of how the actual decision to invade Iraq was made; no indication that the pros and cons of such an invasion were debated; no sign of a policy process that allowed all views to be heard; and no references to any after-action reviews investigating how the failure of intelligence had enabled such a catastrophic misreading of the fact that Saddam Hussein had destroyed his biological and chemical weapons a decade earlier and had no active nuclear weapons program.

The Early Days

The memoirs do provide some new information about how 9/11 became a pretext for the Iraq War. Even before 9/11, Rumsfeld said he had sent a memorandum to Cheney, Rice and Secretary of State Colin Powell, suggesting a principals’ meeting to develop policy toward Iraq “well ahead of events that could overtake us.”

Unintentionally, the memoirs also demonstrate the chicanery of these principals in taking uncertain and ambiguous intelligence and exaggerating it to create their own facts. But the memoirs do not discuss the key fact that, the day after 9/11, the President asked Richard Clarke, the NSC’s leading specialist on counter-terrorism, to “see if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way.”

Every agency and department of government understood that there had been no cooperation between Saddam and al-Qaeda; a memorandum to that effect was sent to the President. But the Pentagon’s focus had already shifted from al-Qaeda to Iraq, reflecting the views of Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz, who believed that Iraq was the state sponsor for both the attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 as well as 9/11.

Of course, the memoirs don’t contain admissions that the Bush administration first decided to invade Iraq and then looked for rationalizations that could be sold to a frightened public to justify war. Predictably, all the principals claim innocence and blame faulty intelligence, which supposedly convinced them that Saddam Hussein possessed WMD and might share it with al-Qaeda, thus forcing Bush’s hand.

But the speeches of the President and the Vice President made clear their readiness to go beyond evidence to justify an invasion of Iraq. The speeches themselves testify to the willingness of senior leaders to present phony and exaggerated intelligence to the Congress and the American people.

When CIA Director George Tenet made his infamous remark that it would be a “slam dunk” to provide intelligence to justify going to war against Iraq, he was responding to the President’s demands for intelligence to convince the American people and the international community about the need for war, not to support the Bush administration’s decisions regarding the use of force against Iraq. That decision to invade was made long before the intelligence was in. What Tenet was saying was that it would a “slam dunk” to pull together some scary material that could be sold to the public.

Nearly ten years after the start of this egregious and unconscionable war, it should be the job of the U.S. news media to focus on the immoral and illegal aspects of the decision to take the country to war, and not just on the political food fight surrounding Secretary of State Powell’s infamous speech to the United Nations several weeks before the war began.

But that would require some soul-searching among the major news organizations. The media, particularly the New York Times and the Washington Post, made it too easy for the United States to go to war against Iraq. Any retrospective must scrutinize the conventional wisdom that dominated the run-up to that war as well as the deceit of the nation’s highest leaders.

Melvin A. Goodman, a former CIA analyst, is a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University. His most recent book is National Insecurity: The Cost of American Militarism (City Lights Publishers).

Cheney started a war that his former company derived an enormous financial benifit from thus, justifying the more than eighty million dollars they paid him over eight years. Bush went along with it because he wasn’t smart enough not to.

“it should be the job of the U.S. news media to focus on the immoral and illegal aspects of the decision to take the country to war”

.

Many refer to the Iraq war as “Rupert’s War” and the likely hood of the U.S.news media focusing on the immoral and illegal aspects of the decision to take the country to war” seems to be a stretch.

.

The MSM propaganda in favor of war was overwhelming whereas the largest protest in history happened on February 15, 2003 when over 15 million people marched against the war in Iraq, in over 800 cities around the world and it received scant coverage from the MSM.

We are at last beginning to see the real history of the Iraq war.

.

Since before WWI Western Imperialistic Christian powers have destroyed the “Middle East”.

.

The borders of Iraq were drawn by Winston Churchill who had never even visited Iraq.

.

Iraq sometimes called the cradle of Civilization was at the forefront of Arab countries with a very high levels of literacy , high standard of living & education standards & equality for women & excellent medical facilities.

.

http://www.alternet.org/story/68568/holocaust_den…

.

The CIA’s Susan Lindauer in her book points out that Iraq was never a threat to the US but she and many experts agreeing that no WMD were there were not listened to by the USA.

Without addressing the lead up to the Iraq War or what Bush Administration officials have since said to deny or obfuscate their responsibility, i.e., the subject of this article, and without commenting on Rehmat’s assertion that the Mossad planned or was complicit in the 9/11 attacks, the reasons underlying, and leading up to the Afghanistan war offer a set of reasons and obfuscations analogous to the Iraq fiasco.

From many accounts, the Administration had decided a month or two prior to 9/11 to invade Afghanistan, and, in George W. Bush’s words, “bomb it into to stone age” after the Taliban, who had been wooed and wined and dined in Houston, wouldn’t bite and let themselves be nickel and dimed by the Bush family’s favorite oil company, Unocal, the U.S. company demanding exclusive development rights for a TAPI pipeline. It was also not inconsequential that Afghanistan’s mineral resources were being mapped, or that they promised to yield huge returns (or it so seemed) to any who might get the concession to extract them. So, 9/11 became the convenient (and trumped up) ‘casus belli’, when Afghanistan would not turn over Osama bin Laden, even though the FBI and CIA would not certify that he and his buddies were likely responsible for the WTC crime (though, at the time I wondered why we never asserted the stronger case of his complicity in the U.S. embassy bombings and the attack on the U.S.S. Cole as the reason for demanding his extradition, unless there was something screwy, or that we did not want to disclose there as well). Who knows, maybe we would have found out, as we did later, that he and Zawahiri were also our sometime allies in other ventures. In any case, failure to make a showing that he and his crew were the ones meant that our invasion of Afghanistan was instead a war of aggression, not a war of self defense, and that therefore the Taliban could not have been a force “associated with†someone who could not be certified as the enemy who planned and/or executed the WTC bombing. If so, then the Taliban’s subsequent attacks on the U.S., even up to today, could not be construed as the work of terrorists, as opposed to freedom resistance fighters. Though, I maybe right now it would be a waste of time to tell an apoplectic John McCain, or any of his terror war-fixated colleagues that.

We all know that the reason for the invasion of Iraq was a result of Zionist control of the USA and Israel’s fear of Iraq’s developing missile technology. However, now that the ‘principals’ have confessed to the error in their intelligence (LoL), the USA and Britain are surely liable for huge reparations – the Iraqis should sue.

Rehmat is right – the freedom fighters are labelled ‘terrorist’ whilst the initiators of terrorism in the Middle East were the Zionists and the illegitimate State of Zion has been and remains the most despicable terrorist organisation in the World.

The bottom line is that these monsters are war criminal. They should already have been tried and hanged–should have joined innocent Saddam.