The pundits say America’s economic angst will trump worries about war in the Nov. 6 election. However, as Americans learned a decade ago, careless foreign policies can have disastrous consequences, a lesson that ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar also traces back one and two centuries.

By Paul R. Pillar

As this year’s presidential campaign turns to debates about certain foreign conflicts and controversies with the potential for sucking the United States into war, here is an anniversary-based fact that does not seem to have received notice, certainly nothing like the Cuban missile crisis did this month upon its semicentennial.

The presidents of the United States who were elected 200 and 100 years ago both led the nation into war. Both did so despite earlier indications of personal hesitation and reservation in doing so.

The United States entered war with Britain during the final year of James Madison’s first term. The impetus for war came principally from congressional war hawks from the West and South such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.

When Madison sent to Congress in June 1812 what became known as his war message, it did not explicitly ask for a declaration of war. Instead it only listed the maritime and other grievances that the nation had against the British. Congress did declare a war, “Mr. Madison’s war”, in which Madison would become the only U.S. president to be chased out of the White House by foreign troops.

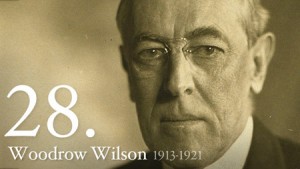

A century later, as the European powers sank into the carnage of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson said to his aide Colonel House, “Madison and I are the only Princeton men that have become presidents. The circumstances of 1812 and now run parallel. I sincerely hope they will not go further.”

Wilson was elected to a second term in 1916 aided by the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” But only a few months later he asked for and received a congressional declaration of war. The United States was on the winning side of that war, but mismanagement of the aftermath set the stage for another ghastly European war two decades later.

Notwithstanding the many differences, there are some parallels between the circumstances of a century and two centuries ago and those of today. Let us sincerely hope the parallels will not go further.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

US citizens know so little about our policies abroad, but our misadventures abroad are the primary, not the only but the primary, reasons for our social turmoil here at home. We like to think of ourselves as the savior of post WW II Europe via the Marshall Plan, the breadbasket of the world, the riders to the rescue of tsumanis, earthquakes, etc. We are not all bad, but we can’t, or won’t, hear anything about our horrific miscalculations.

db your knowledge of history is visibly immature in what you write and I don’t have the inclination to educate you.

But you seem quite youthful and need time and a lot of research to formulate your ideas.– good luck.

“The Germans tried. Tried to start a war between the US & Mexico.”

Like Saddam Hussein wanted to attack the USA with his WMD’s

“tried” ? All the Germans wanted in 1917 was an end to war but the Great British Empire did not want peace without victory and rejected German overtures.

At the beginning of 1917 the USA was in a position to bring about an IMMEDIATE peace to the “world”

http://www.amazon.com/Churchill-Hitler-Unnecessary-War-Britain/dp/0307405168

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/whose-war/

Pearl Harbor see http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article29905.htm

Hillary,

The Germans wanted an end to the war in 1917. Sure but they wanted to hold onto their conquest of Belgium. Look at the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. You can see what kind of peace the German Empire wanted.

““The Germans tried. Tried to start a war between the US & Mexico.â€

Like Saddam Hussein wanted to attack the USA with his WMD’s”

Your analogy is inaccurate. The German threat was immediate & specific. Much m ore like what Saddam did in fact do to Kuwait. The only difference was that Saddam was effective, the Germans were not.

I’d suggest you dig up an old book. It’s entitled “You Can’t Do Business with Hitler”. Written by the American Businessmans Committee Against Fascism (1941)

Don’t worry about needing to “educate” me. I have no wish to enter your world fantasy world. At a distance I suspect opiates.

Tell me again how the Jews attacked Pearl Harbor. We haven’t lost all of that generation yet. Ask some of them.

Nucking Futz

Citing partick Buchanan’s book? There’s a real authority for you.

“Citing partick Buchanan’s book? There’s a real authority for you.”

??

Perhaps you are not aware that the title of the book came from Winston Churchill himself, from his preface (p. iv) of “The Gathering Storm”?

One day President Roosevelt told me that he was asking publicly for suggestions about what the war should be called. I said at once “the Unnecessary War.”

Sure, but you’re either intentionally or otherwise misstating the arguments. Both Churchill & Roosevelt felt (as I do) that WWII could have been prevented by taking a strong stand against Hitler at some earlier time between 1932 & 1938.

Not that the free World should have knuckled to the Nazis.

Not that the Jews somehow started the war for nefarious purposes of their own.

rehmatshit and herr hillary are high on some kinda drug.

Yes, but it’s a drug I thought safely buried in 1945.

WWI and WWII were un necessary wars.

Today most historians agree that the Zimmerman telegram lay well within Germany’s rights. It expressly stated that the alliance against the United States was only to be attempted if and after the fact was certain that there was to be “an outbreak of war” .

It was used as the clincher in the Zionist campaign for a pre-war sentiment in the U.S. to join Britain in return for “giving” Palestine to the Zionists while German WWI peace proposals were being declined.

The Zimmerman telegram included an agreement for a German alliance with Mexico, while Germany would still try to maintain a state of neutrality with the United States. If this policy were to fail, the note suggested, the Mexican government should make common cause with Germany, try to persuade the Japanese government to join the new alliance, and attack the US. Germany for its part would promise financial assistance and the restoration of its former territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona to Mexico.

“What strikes one most about the Zimmermann note today is not its perfidy, but its folly, its utter folly and futility. Mexico knew well that no German ship, no aid in men or in munitions, could possibly reach her. She delighted much in annoying the United States; but what chance was there that she would deliberately invite destruction by declaring war to oblige Germany?

Or, even if we conceive Mexico guilty of such murderous madness, what effect could it have upon the United States beyond the holding of a few thousand troops upon the southern border, while the rest of the nation turned with increased anger and determination to Germany’s overthrow?”

Hilary,

I happen to agree with President Theodore Roosevelt that the US should have entered the war when the German Reich invaded Belgium. That aside I agree wholeheartedly that the Zimmerman telegraph was both foolish & futile. Still it happened. Germany urged the Mexicans to attack the US in the event of a war. The fact that the Mexican Govt. was in the middle of a revolution, the Japanese were allied to the British, and Germany’s ability to assist the Mexicans in such a war were nil; makes no difference. The Germans tried. Tried to start a war between the US & Mexico.

Your saying that the Zionists dragged the US into the War? “Jewish Bankers” controlling the world is more often an argument if the Libertarian Right than the Left. The idea was popular in the 1930s.

You state the WWII was unnecessary? You’re saying that the Japanese did not attack Pearl Harbor? You’re saying that Nazi Germany & Italian Fascists did not declare war on the US?

What would you have had the response to the attack on Pearl harbor to have been?

Nucking Futz.

With respect to Prof. Pillar, the US did not lightly enter WWI.

The German Empire engaged in a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. They claimed the right to sink, without warning, any ship sailing within a specified range of the British Isles. They sank the passenger liner, Lusitania, in the summer of 1916, with the loss of over 1500 check number) lives. This was the 1916 version of “State Sponsored terrorism”. The US Government warned of the severest consequences if the Germans persisted. The Germans ended the policy of “unrestricted warfare” but re-imposed it in early 1917.

Additionally the Germans attempted to start a war between the USA & Mexico. The telegram, promising Mexico vast quantities of teh American south-west in the event of entering the war, was intercepted by the British, de-coded, & turned over to the US. It’s known as the Zimmerman Telegram.

Hardly light or transient reasons. Hardly a “stumble”. “Sucked”? Hard to say, but pretty well necessary.

Did you not remember the Lusitania was found to have been crammed with weapons?

btw, the behaviour you mentioned sounds eerily parallel to the USA this century and earlier.

rosemary,

The presence of weapons on the Lusitania has been argued by German apologists since 1916. I don’t have access to do more research so the less said the better on my part.

The Lusitania was just one of many civilian ships sunk under the unrestricted submarine warfare. Greatest loss of life though. A single incident did not force the US to war. It was a long line of continued sinkings.

I do not understand the reference to “the behavior”. Sending weapons into a war zone? Opposing State Sponsored terrorism?

Rehmat,

The Jews caused WWI & WWII? The Jews caused the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor? The Jews caused the Cold War? What paper do you read? The Volkish Beobacher?

“with the potential for sucking the United States into war”

The US so easily sucked into war ?

Vietnam and Iraq to mention just 2, totally illegal , totally shameful.

The slogan of the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s “1984,â€

“Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.â€

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IAwPqfJqccA&feature=related