The U.S. press is playing up claims that Iran is “sanitizing” evidence of nuclear experiments at a military site, but experts say Iran knows nuclear residue can’t be erased, suggesting the Iranians may be engaged in a negotiating ploy to boost the trade-off value of the site, reports Gareth Porter for Inter Press Service.

By Gareth Porter

The International Atomic Energy Agency and Western governments acted this week to escalate their accusations that Iran has “sanitized” a site at its Parchin military complex to hide evidence of nuclear weapons work, showing satellite images of physical changes at the site to IAEA member delegations.

The nature of the changes depicted in the images and the circumstances surrounding them suggest, however, that Iran made them to gain leverage in its negotiations with the IAEA rather than to hide past nuclear experiments.

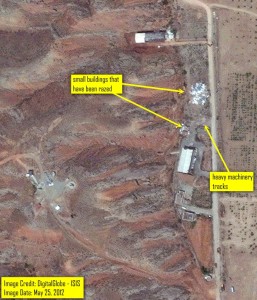

The satellite images displayed to IAEA member delegations last week by Deputy Director General Herman Nackaerts, head of the agency’s Safeguards Department, showed a series of changes that have been the subject of leaks to the news media: a stream of water coming out of building at a site at Parchin, the demolition of two small buildings nearby the larger building said by the IAEA to have housed a bomb containment chamber, and earth moved from locations north and south of the site to be dumped further north.

After seeing the pictures, U.S. Permanent Representative to the IAEA Robert Wood declared, “It was clear from some of the images that were presented to us that further sanitization efforts are ongoing at the site.”

But the activities shown in those satellite images show activities appear to be aimed at prompting the IAEA, the United States and Israel to give greater urgency and importance to a request for an IAEA inspection visit to Parchin in the context of negotiations between Iran and the IAEA. The latest round in those negotiations, on a framework for Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA in clearing up allegations of Iranian covert nuclear weapons work, failed to reach agreement on Friday.

Greg Thielmann, former director of Strategic, Proliferation and Military Affairs Office of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, said in an interview with IPS that he didn’t know whether the changes shown in satellite images were part of a conscious Iranian negotiating strategy. But Thielmann, now a senior fellow at the Arms Control Association, said the effect of the changes is to “increase the interest of the IAEA in an inspection at Parchin as soon as possible and to give Iran more leverage in the negotiations”.

Nuclear scientist Dr. Behrad Nakhai, who has worked at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and has closely followed the Iranian nuclear program, suggested that Iran’s overt moves on the ground in Parchin were a way of ensuring that “the IAEA will be enticed to give more value to an inspection of Parchin.”

Muhammad Sahimi, who tracks news coverage and comments on Iran’s nuclear program for the PBS Frontline website “Tehran Bureau,” agrees that Iranians have made physical changes at Parchin “so that when they allow the IAEA in, it will be at a higher price.”

Access to Parchin has been recognized implicitly by both sides as Iran’s primary leverage in those negotiations. The IAEA has insisted in the past that a Parchin visit must come before reaching the broader agreement on Iran’s cooperation, while Iran has refused to permit a visit to the site until after the agreement is completed.

The primary issue in the wider negotiations has been whether the IAEA inquiry would end if and when Iran answered all the questions that have been raised by the IAEA or whether the agency could go back to issues as often and whenever it wishes.

The charge that Iran is “sanitizing” the site assumes that Iran believes that the activities depicted would actually eliminate traces of radioactivity left by past testing at the site. The IAEA’s November 2011 report said a bomb containment chamber at the site in Parchin was used for “hydrodynamic tests,” which utilize natural or depleted uranium as a substitute for fissile materials.

David Albright, director of the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), suggested in a May 11 commentary on the organization’s website that if Iran were to grind down the surfaces inside the building, collect the dust, wash, repair and repaint the building, and remove dirt around the building, it “could be effective in defeating environmental sampling.” But nuclear experts have contradicted that statement. [For more on Albright, see Consortiumnews.com’s “An Iraq-WMD Replay on Iran.”]

Pierre Goldschmidt, IAEA deputy director general for safeguards from 1999 to 2005, responding to an e-mail query from IPS, said, “Of course there would be no way to remove the traces of a nuclear test.”

Robert Kelley, who has also managed the U.S. Department of Energy’s Remote Sensing Laboratory, which specializes in high-tech detection of nuclear activities, and was twice head of the IAEA’s Iraq inspection group, has pointed out that Syria was sent to the U.N. Security Council over a site that had been bulldozed a year earlier, because of the discovery of tiny microscopic particles of radioactive material found at the site. Nuclear scientist Nakhi told IPS, “It’s virtually impossible to clean up radiation from a nuclear test completely.”

Referring to the charges of “sanitization” of evidence of nuclear device testing at the Parchin site, Seyed Hossein Mousavian, Iran’s lead nuclear negotiator with the European states in 2005, told IPS, “Iranians know very well they couldn’t eliminate traces of such activities even after 10 years.” Mousavian, now a visiting scholar at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, added, “I personally cannot imagine there were such activities (at Parchin).”

Nakhai told IPS in an interview that Iranian officials are also acutely aware of the fact that everything they are doing at the site is being tracked by Western intelligence agencies through spy satellites. The physical changes that have been carried out at Parchin, he suggests, have been deliberately staged for IAEA and Western governments. “The only thing missing is somebody waving to the satellite,” Nakhai said.

Former nuclear negotiator Mousavian would not comment directly on whether Iran is making changes at Parchin to increase the negotiating value of permitting an IAEA inspection. But he told IPS that, in the end, “Iran will be able to prove to international opinion that this accusation is false.”

The satellite images shown to the IAEA member states were published May 8 and May 30 by ISIS. The earlier picture, dated April 9, showed the stream of water emanating from the building. The later images, dated May 25, showed the demolished buildings and evidence of earth having been moved.

The changes at the site shown on the satellite images appear to have one thing in common: they all lead the IAEA directly to places on or near the site where environmental sampling can be done easily by an IAEA team. The water shown in the April 9 image appears to collect in a ditch a short distance away from the building.

Former IAEA senior inspector Kelley observed in a May 23 article on the website of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute that the IAEA team would have an “enhanced opportunity” to find uranium particles if they were present.

The May 25 image appears to show soil that was moved from two areas roughly 200-300 feet north of the building and 100-200 feet south of it. But the soil appears to have been carried only a few hundred feet further north of the former area where it is shown to have been dumped, offering another inviting target for environmental sampling.

The fragments of the two small buildings demolished at the site appear in the May 25 image to have been left intact on the ground, offering yet another easy objective for a visit. Meanwhile, the building in which the IAEA reported last November that a bomb containment chamber had been used for hydrodynamic testing and the soil south and east of it remain undisturbed.

The claim that such a chamber was installed at a site in Parchin in 2000 to carry out hydrodynamic testing appears to depend entirely on unspecified information from unidentified countries. The claim has been challenged by Kelley, making no sense on the basis of technical inconsistencies.

Gareth Porter is an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy. The paperback edition of his latest book, Perils of Dominance: Imbalance of Power and the Road to War in Vietnam, was published in 2006. [This article originally appeared at Inter Press Service.]

Which liars are we supposed to believe? The presstitute, our government, or the Iranians?