Almost unknown in the U.S., Hajjar heckled Ben-Gurion, joined the civil rights movement in the South, and lost his job with the PLO for allegedly insulting Arafat.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Most Americans—and most Arabs—have not heard of George Hajjar (he used to spell it Haggar when he lived in Canada and the U.S.), one of the most politically eccentric academics ever.

Most Americans—and most Arabs—have not heard of George Hajjar (he used to spell it Haggar when he lived in Canada and the U.S.), one of the most politically eccentric academics ever.

This is a man who gave up many jobs and income security for his firm belief in his principles and dedication to revolution. Hajjar’s career represents an unusual path of an Arab academic—or any academic.

As is well-known, Arab intellectuals in the West (like Edward Said, Hisham Sharabi, and Ibrahim Abou Lughod) only became vocal about Palestine after the 1967 defeat, which shook the conscience of Arabs worldwide. Hajjar, to his credit was vocal about Palestine from very early on, and never wavered in his fierce opposition to Zionism as soon as he stepped foot in North America in the early 1950s.

As a young man in Canada in 1960, he chased David Ben-Gurion in Canadian airports to heckle him and to protest the occupation of Palestine. He realized that Palestine is the defining cause and was warned early on by Canadian academics that Israel is a sacred cow in the West, and that being a communist is much easier in comparison. Hajjar was both: an avowed radical Marxist and a fierce anti-Zionist.

This brave academic revolutionary was fired from every university job he ever held, except his last job at Lebanese University in the Biqa`. Following Marx’s dictum, Hajjar (who studied political theory) was not satisfied in interpreting the world; he wanted to change it, and he did change the world around him in every period of his life, and contributed to the Palestinian revolution.

If academics are pleased to hear applause at the end of their talks, Hajjar was more ambitious. He wanted to lead his audience to revolution in the 1960s in Canada and the U.S.: he was a leader of union and student revolts at several universities. He founded one of the early Canadian Arab political organizations.

Hajjar tells his life story in his book Revolutionary Wanderer in a Changing World (Arabic, published by Dar Al-Farabi). Hajjar grew up in a poor family in Biqa` (Eastern Lebanon) and described in his memoir political developments around him in the 1930s and 1940s in uncompromising language. He rightly refers to Lebanon’s independence heroes as “tails” of colonialism (p. 23).

His father sought to turn Hajjar into a monk but young Hajjar did not last, and fled the monastery on foot until he returned home. This is a man who could not be tamed by governments, political parties, or religious authorities.

In 1952, Hajjar immigrated to Canada and worked as a waiter and shoe shiner. He learned English and excelled academically. He is frank in informing readers that his professors were shocked at his fierce revolutionary style in research papers (p. 70). Academia works to harmonize and tame students’ language so that we all sound the same and not pose a threat to the existing order that universities train us to obey and serve.

Hajjar entered Canadian party politics and protested inside the Canadian parliament in 1961 against Israeli nuclear weapons (even today, just compare the enormous Western media attention to non-existent Iranian nuclear weapons program to the existing massive nuclear arsenal of Israel).

His Canadian fiancé was alarmed at his revolutionary activities especially when the daily hometown paper carried a picture of Hajjar holding a sign against “Nazi generals” in reference to the U.S. war in Vietnam (Hajjar refers to that as “political entertainment” (p. 86).

In 1963, he had a son who he named Bertrand, after Bertrand Russell. Hajjar earned his PhD in political theory from Columbia University in 1966, and got a job at Waterloo Lutheran University, but he was subsequently fired (or his contract not renewed) purely for his revolutionary approach and activities. Hajjar was a pioneer in Canadian Arab political organization at a time when Arabs in North American were too afraid to express their political beliefs for fear of arrest and deportation.

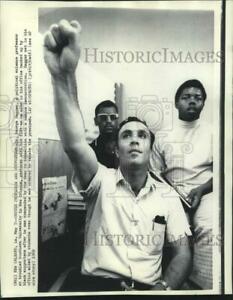

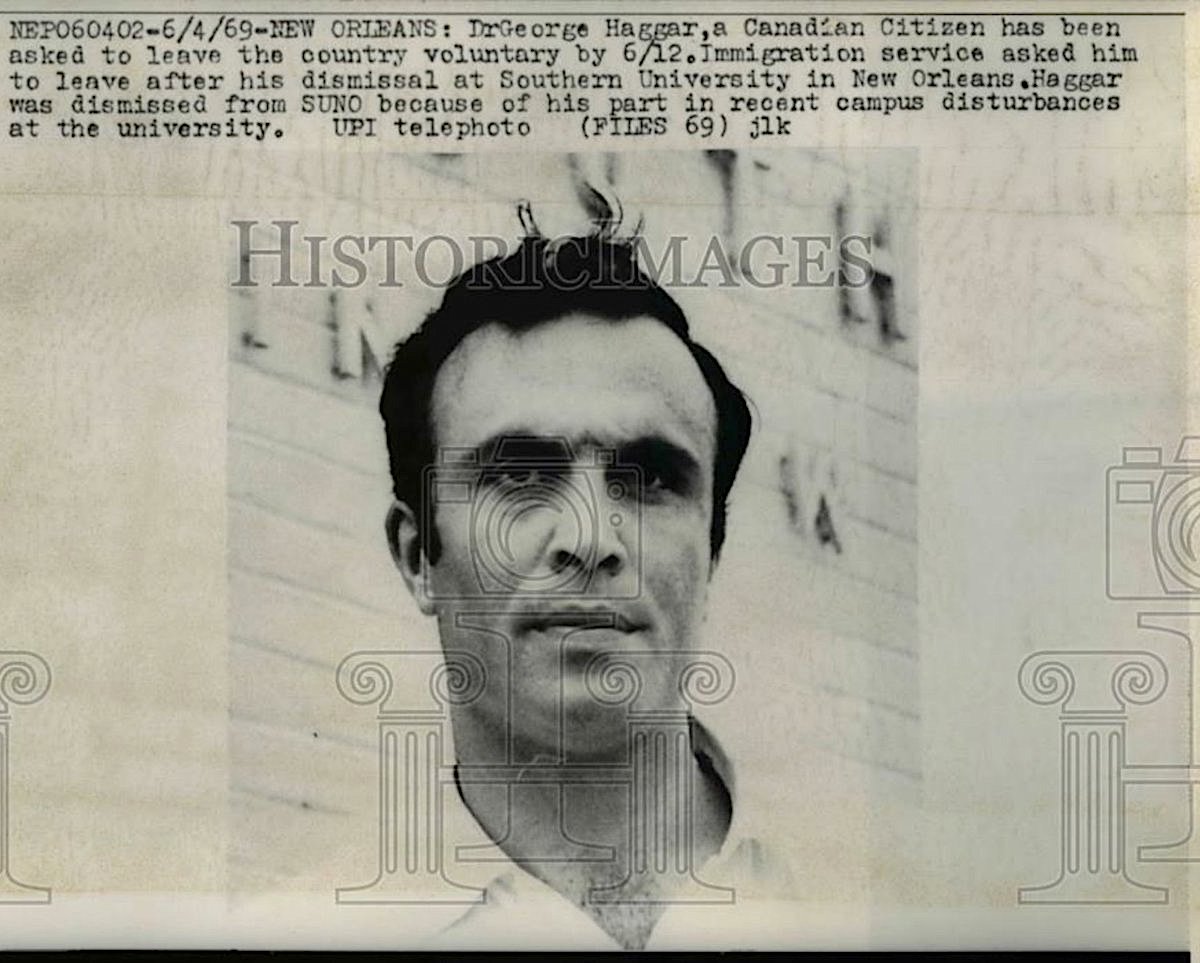

Hajjar’s reputation spread in North America (he was a featured speaker in the conference of Arab Student Union in Long Beach in 1970) and the predominantly black, Southern University in New Orleans (SUNO) extended an invitation to him to join its political department. He quickly became a leader of the black student rebellion, on and off campus.

A student protest ensued and Haggar was fully trusted by the students, who made him their quasi-spokesperson. Conservative elements on campus started maligning Hajjar and undermining his revolutionary credentials as the leader of the protest. He was called White and Hajjar explained that he never considered himself white and asserted that he identifies as a brown person.

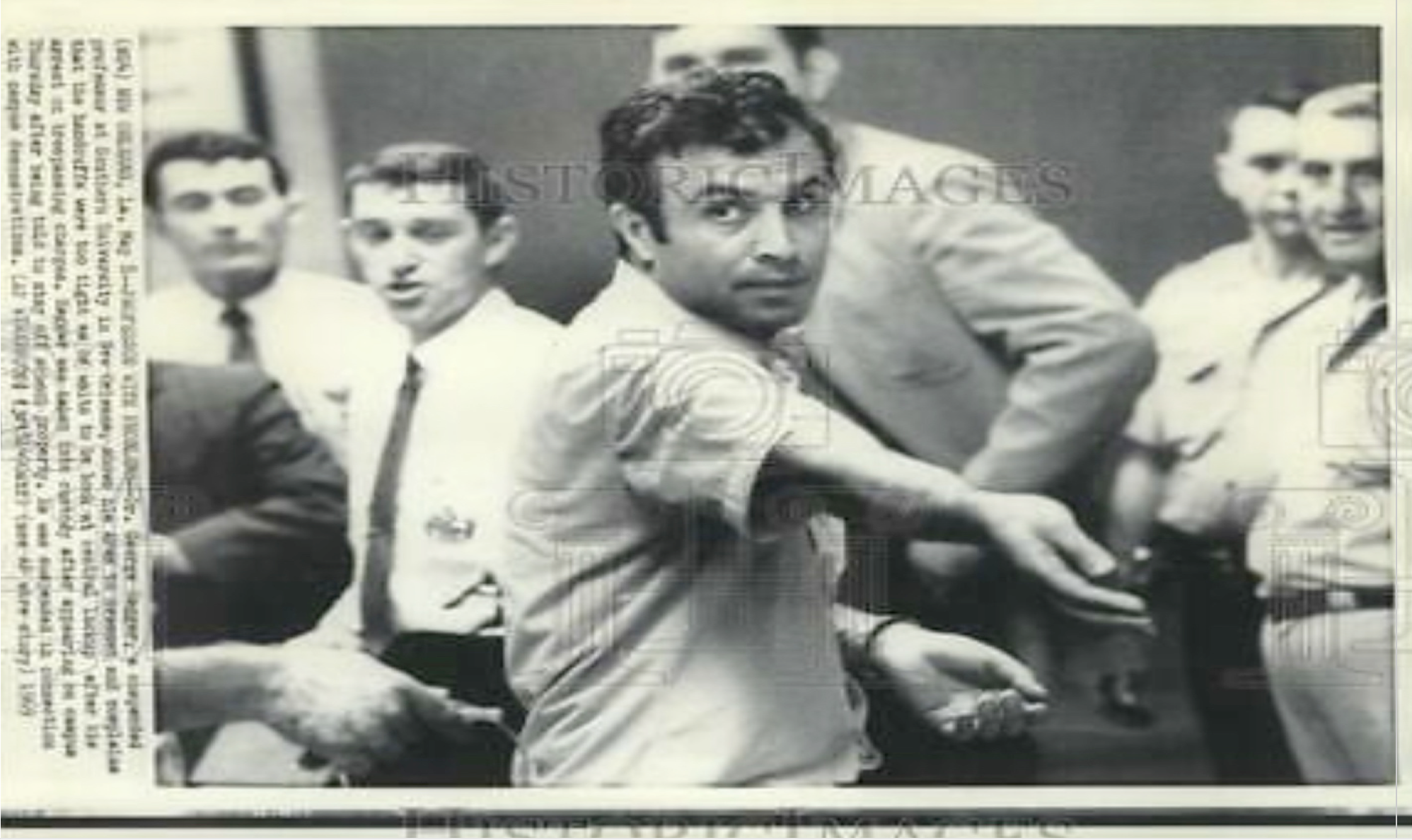

The protesters confronted Louisiana Governor John McKiethen, who was then held “hostage” (it was ironic that Hajjar, who had no U.S. citizenship and not even a Green Card, assured the governor that as long as he stayed with him during the protest, he would be safe). Hajjar quickly became an enemy of the state. The police chief of New Orleans addressed Hajjar on camera on TV, while Haggar watched and laughed.

Hajjar reports in his book the scene of helicopters and police cars going after him before his arrest. Adam Fairclough, in his Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972, acknowledges that the history of the civil rights movement in Louisiana recognizes the role of Hajjar at Southern University and says that conservative black faculty members made blatantly racist appeals to the students in an effort to discredit Hajjar, “an Arab-American political science professor whose fiery denunciations of ‘Fascist niggers, house niggers, black bourgeois masochists, [and] white liberals’ had given him notoriety and influence”” (p. 433).

SUNO fired Hajjar and he was deported from the U.S. in 1969. Congressman Gerald Ford railed at this Arab-American academic who held a U.S. governor hostage.

Return to Lebanon

Hajjar’s reputation grew and Basil Kubaisi, an Iraqi who was active in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) while pursuing his PhD in Canada, and who would later be assassinated by Mossad in 1973 introduced him to PFLP circles in Beirut. Hajjar’s return to Lebanon launched a new revolutionary career for Hajjar.

He met Ghassan Kanafani, Wadi` Haddad, and Leila Khaled among other leaders of the Popular Front and other Palestinian resistance organizations. Hajjar was interested in introducing the Palestinian cause to the world through a biography of Leila Khaled. But Hajjar did not hit it off with the PFLP crowd in Beirut.

He came across as arrogant and supercilious (as one contemporary of Hajjar reported to me when I recently asked him about Hajjar). Kanafani and others made critical remarks of a Hajjar manuscript and he angrily published it in the UK (under the title My People Shall Live, and it became a best seller in several languages).

Hajjar also wanted to join the ranks of the PFLP leadership but without going through the organizational hierarchical ladder. The PFLP refused, but Wadi` Haddad was impressed with Hajjar and recruited him to work as a full-time cadre, and utilized his services in his operations.

In the book, Hajjar mentions the Lufthansa hijacking into Mogadishu in 1977. His role was presumably strictly to analyze the political context and draft the political manifesto for the operation. Hajjar would not have been privy to any military planning and he does not seem to ever had any military role.

It should be noted that the mother organization, the PFLP, distanced itself as early as 1971 from “international operations” and condemned the harm they do to the Palestinian cause and the potential risk to civilians. The violent act involved hijacking a German commercial airliner and demanding the release of Palestinian (and German Rote Armee Fraktion) prisoners. It failed and most of the hijackers were killed as well as the German co-pilot.

After the organization fallout with the PFLP leadership, Haddad tasked Hajjar with writing a book on Ghassan Kanafani after his assassination in 1972. Again, the PFLP leadership did not approve of Hajjar’s account especially since he used the occasion to blast the accommodationist trends of the PLO (he even insinuated that Kanafani would have committed suicide had he witnessed the concessions that started with the PLO’s conference in 1974). [This book was never published and I am currently in talks with Hajjar about its ultimate release].

Hajjar worked at the Palestine Research Center but his personality clashed with that of its president, Anis Sayigh, who managed the center extremely tightly and rather formally, and with great discipline. Hajjar also suggested that he was targeted by Palestinian intellectuals, Hisham Sharabi and Ibrahim Abou Lughod, because he stood firmly against the two-state solution and prophetically warned against a “Jericho republic” in 1974 after attending the PNC’s 12th conference.

The radical reputation of Hajjar swept Beirut and leaders of the Fath (Fatah) Movement summoned him to a meeting and he warned of an incoming wave of repression in Lebanon (shortly before the right-wing militias sparked the civil war) and called for burning of the fashionable Hamra street.

Fath leaders were horrified at the suggestion. Hajjar was then recruited to work for the newly formed Joint Information Committee of the PLO but he also did not last there because he was accused of insulting Yasser Arafat.

Hajjar then moved to Kuwait where he taught at Kuwait University and wrote for its progressive publications. But his stay in Kuwait did not last either and he was fired and expelled for “cursing” the Saudi royal family. He then joined the Institute of Palestine Studies at Baghdad University where he renewed contacts with Wadi` Haddad.

Unsurprisingly, Hajjar drew a gruesome picture of Baghdad under Saddam and wrote: “Baghdad of the Arabs have become Baghdad of mercenaries, opportunists, and vendors of illusory publications” (p. 278). In 1977, he participated in launching the “The Arab Revolutionary Movement” but he resisted an attempt by Carlos (the Jackal) to co-opt his movement on behalf of Saddam Husayn.

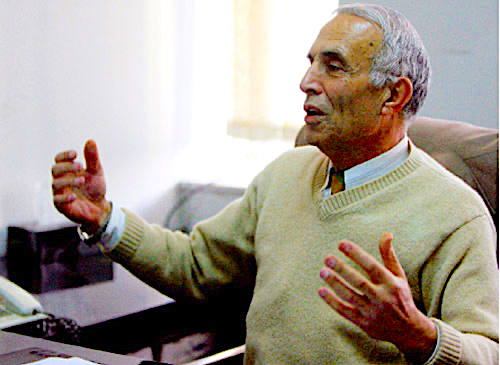

Hajjar subsequently moved to Algeria in 1978 but he quickly clashed with those on college campuses who resisted his Arabization campaign. He was also then expelled from Algeria and returned to Lebanon where he has lived since, and taught at Lebanese University.

He wrote and made speeches and was an early advocate of armed resistance against the Israeli invasion of 1982. (See his book, The Israeli Invasion of Lebanon and Armed Resistance, in Arabic). He coined the slogan: “Palestinians of today, and Armenians of tomorrow if we don’t fight.”

Such was the long revolutionary career of Hajjar, in which he sacrificed what could have been a comfortable academic career. His uncompromised and revolutionary tone from recent exchanges has not softened at all.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Thank you for this important and well-written history lesson. Interesting that Hajjar’s only Wikipedia page is in Catalan: hXXps://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hajjar. Hopefully he gets an English one soon.

Not too many people who have struggled so bravely for so many years. Nelson Mandela comes to mind.

Thanks again for the history lesson.