Jamil Hilal traces the history of Palestinian leadership from elitist to grassroots in the 1960s and 70s to its dire situation today, post-Oslo.

Palestinian children walk past a mural that depicts former Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip, July 22, 2015. (Abed Rahim Khatib)

By Jamil Hilal

Al-Shabaka

The largely traditional leadership pre-1948 – whether semi-feudal or religious – was not in a position to organize the Palestinian people because it was largely disconnected from their lives and concerns. These leaders did not represent the mass of peasants or workers; small or landless peasants at the time constituted over 55 percent of the population.

The largely traditional leadership pre-1948 – whether semi-feudal or religious – was not in a position to organize the Palestinian people because it was largely disconnected from their lives and concerns. These leaders did not represent the mass of peasants or workers; small or landless peasants at the time constituted over 55 percent of the population.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War the British colonial rulers needed laborers in the ports and in other sectors, expanding the working class in the major cities which had formed a strong trade union movement. The traditional leadership of the Jerusalem-based Husseini and Nashashibi families was also disconnected from this movement.

The mass confrontations that faced the British colonial power and the growing Zionist movement largely emerged from peasant, worker and urban professional mobilizations rather than calls by the land-owning and clerical leadership. There were organized groups in the earlier part of the 20th century but up until the 1930s there were only two political parties – the communist party, which was active with the new working class, and the Nablus-based liberal reform party Hizb Al-Islah.

Indeed, at that time the concept of national representation was not yet clearly articulated. When it was expressed it was in opposition to British colonial domination and the Zionist project. The traditional leadership represented families and their interests and believed they had the right to leadership rather than having to earn it democratically. Leadership conflicts arose largely from family rivalry over position and status, although there were political differences as the Nashashibis’ leadership was generally closer to the British while the Husseinis’ leadership was more nationalist.

An Arab protest gathering against British policy in Palestine, 1929. (Wikimedia Commons)

There were many acts of resistance to the British and to Zionist colonization, particularly from the 1917 Balfour Declaration onward. The nationwide Palestinian revolt and strike of 1936-39 was in response to the specific call by the then unified national leadership and drew inspiration from the life and resistance of Sheikh Izzedin Al-Qassam. 2

However, given the traditional style of the leadership it was relatively easy for the British to dismantle it and disperse its members through imprisonment or exile. As is well known, the British were draconian in their efforts to crush Palestinian resistance to their rule, executing and imprisoning many while offering support to the Zionist movement that was building a Jewish state in Palestine.

The emergency laws used by the British to imprison without trial are still used by Israel today. By the 1940s, because of British actions, there was no longer even the semblance of an effective unified leadership to represent the Palestinian people at a critical time.

Overall, the balance of power was heavily tilted against the Palestinians in terms of organization, military capability, and leadership, and their ability to grasp the power politics of the international situation was limited. The Palestinian leadership also lacked sufficient understanding of the internal and international dynamics of the Zionist project.

Furthermore, most Arab countries were under some form of colonial rule and the support they could give the Palestinians was very limited and lacked a clear aim and purpose. The Palestinian leadership, which was scattered and had no organized popular constituency, did not inform or consult the people about various alternatives and policy routes to face both British rule and the Zionist movement. In short, the lack of a unified leadership and an organized popular base was devastating.

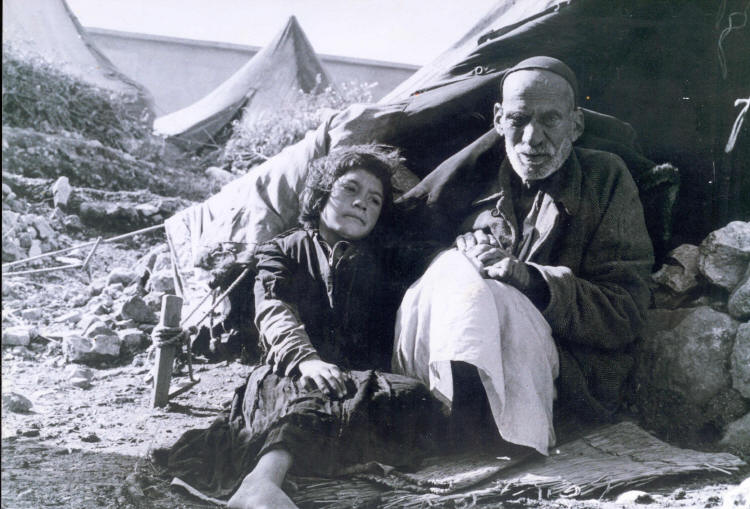

Sudden refugees forever, Palestine Nakba 1948. (Hanini, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By contrast, the Zionist movement was very well organized, well armed, and well equipped; it had the support of the superpower of the day and access to diverse resources. The Zionists also had a clear vision to achieve their aim of building a settler colonial project and a more astute leadership that was willing to accept the 1947 UN partition plan and build on it.

The Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948 resulted not just in the destruction of the Palestinian political field and the elimination of Palestinian leadership; it also destroyed a thriving civil society made up of political parties, workers, youth, women, and other agencies and cultural institutions that had developed despite the continuous assaults against the Palestinians by the British and the Zionists. 3

Indeed, Palestinian civil society had blossomed as early as the 1910s with rich output from Palestinian intellectuals and businessmen calling for a democratic state in Palestine and suggesting ways to develop it. Some of this thinking was captured in the book Reconstruction of Palestine, published in the US in 1919. 4

The PLO’s First Two Decades

1964 Arab League Summit in Cairo. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Arab League established the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1964 to give Palestinians a state-sanctioned role in liberating Palestine. It was designed to be more accountable to the Arab regimes than the population seeking return and self-determination.

After Palestinian resistance groups took over the PLO in the late 1960s, the composition and structure of the organization changed. The new leadership drew on the refugees and the middle class and on the strategy of armed struggle. It was able to build a following amongst Palestinian refugees and exiles as well as amongst Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The social composition of the PLO leadership was radically transformed, as was the constituency it represented and the form that representation took. The PLO was based on a party structure (the parties being the constitutive militant factions) and people had a say in the system. They were offered training and membership, not just in political bodies but also in popular and professional organizations.

The PLO’s base included popular nationalist institutions of workers, women, students, teachers, and writers, and others, all of which cut across political and geographic borders to become a national movement for all Palestinians.

Shatila refugee camp in Beirut, 2003. (CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

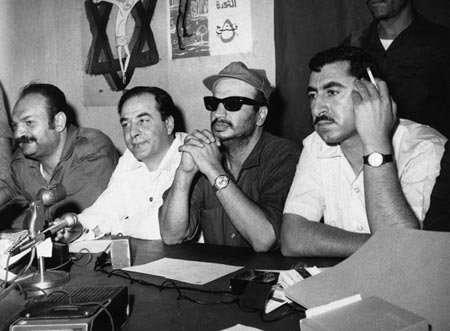

A look at the social origins of the leaders of the PLO’s different factions, such as Yasser Arafat, Khalil Al-Wazir, Salah Khalaf, Nayef Hawatmeh, and George Habash, shows that they came from middle or lower middle class backgrounds. This was very different from the leadership of notables that the Palestinians experienced before the Nakba.

The PLO’s most important achievement was to provide an over-arching structure that brought the dispersed communities together under one narrative, with the sense of being one people with unified aims: When something happened in the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut, people responded in the Yarmouk camp in Syria, in Al-Amari in the West Bank, in Al-Wihdat in Jordan, and in Khan Yunis in the Gaza Strip, as well as in Palestinian towns and villages elsewhere and in the diaspora.

The Oslo Accords destroyed this because they effectively dismantled the institutionalized relations and structures that had been created and fostered under the PLO umbrella.

Yasser Arafat, fourth from right, at Brandenbug Gate during visit to East Germany in 1971. (Franke, Klaus / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Equally important was the leadership’s capacity for strategic thinking at that time and its access to diverse sources of information about world events. The leaders were very well connected to the Arab world, to socialist countries, and to democratic movements in the West.

Each of the PLO’s member organizations had strong connections with Russia or China, and some had links with Western countries through representatives and through relations with left-wing parties and associations of Palestinian living in those countries. The leadership had access to myriad opinions and clashing views from Iraq, Algeria, Yemen, Syria, and others.

Yasser Arafat with Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine leader, Nayef Hawatmeh and Palestinian writer Kamal Nasser at press conference in Amman, 1970. (Al Ahram Weekly, Wikimedia Commons)

During its years in Beirut the PLO leadership met regularly, and discussions frequently lasted for hours until some sort of consensus (ijma’) emerged. The leaders each had access to information from different countries and political strands.

This was not how it had worked pre-1948 or how it works today. In the 1970s Arafat had to listen; he could not ignore what was said, especially as all the groups were armed, although the weapons very rarely pointed inwards, before the PLO was expelled from Beirut in the summer of 1982 and a small Fatah faction split. 5 Each of the main groups had its independent organization and relations with other political and diplomatic sources as well as its own information outlets.

In addition, the leadership had access to papers, studies, and evaluations prepared for them or published by the PLO Research Center and the Planning Center on issues that demanded their attention. They also participated in international meetings. This all changed after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the expulsion of the PLO. The big trap of Oslo was that it disrupted, and eventually marginalized, the tradition of consensus building and access to sources of independent knowledge and assessment.

The unified leadership that led the First Intifada in the West Bank and Gaza Strip that broke out in 1987 was a success because it relied on mass-based organizations that the leadership represented. The leadership was composed of the four political parties actively present in the OPT and, though the leaders remained incognito, people listened to their instructions and directives.

They never posed a threat to the PLO leadership because the leadership inside the OPT was organizationally and politically an extension of the leadership on the outside. The difference was that the local leaders were individuals who were active in their local community and were accountable to it.

The Waning of Representative Leadership

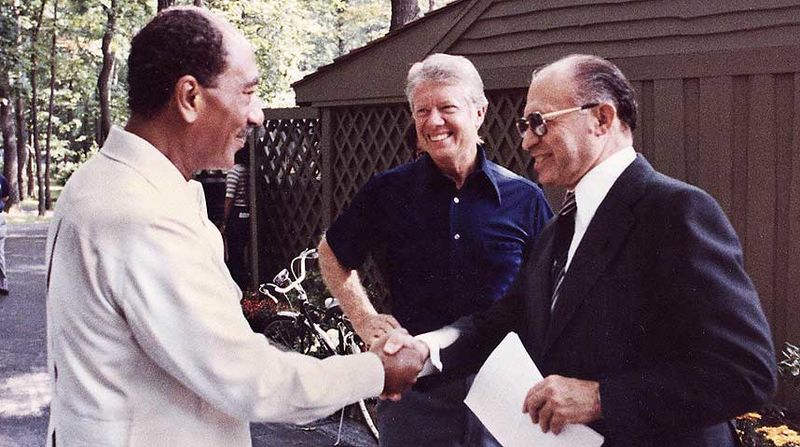

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at Camp David in September 1978. (Wikimedia)

One cannot isolate the Palestinian question and the evolution of its leadership from the developments in the region. The Camp David Accords of 1978 between Egypt and Israel weakened and sidelined the PLO and the Palestinian question.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 gave a boost to the Islamist perspective, and the growing strength of “petrodollars” helped to grow Islamist movements, including those of Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

The Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the siege of Beirut in 1982 fragmented the PLO’s forces and dispersed its leadership far away from Palestine and Palestinian communities.

By the time of the 1988 Palestinian National Council (PNC) the PLO faced considerable pressure from the Soviet Union, European countries, and the United States, which conditioned their hypothetical backing for Palestinian statehood on an entrenchment of Palestine’s partition in the form of UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338.

Thereafter, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the equivocal stance taken by the PLO leadership angered the Gulf States, which starved the PLO of financial resources and political support.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. President Bill Clinton and the PLO’s Yasser Arafat at Oslo Accords signing ceremony, Sept. 13, 1993. (Wikimedia Commons)

The political, economic, and diplomatic pressure to do a deal was very strong. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the decision to enter into the Oslo Accords was not taken by consensus of the whole leadership.

Today, the PLO is hollowed out by the creation of the PA, which itself is facing the axe of further fragmentation and Israeli annexation. The question now is how long can the PA continue to function with its present structure and leadership – a leadership that is not recognized by the Palestinian people but tolerated by the international system because of its need for an interlocutor, and so dependent on international support that it continues to perform security functions for the occupying power.

The PLO leadership chalked up many successes in the 1960s and 1970s. It functioned in a very threatening environment, though it had friends in every corner of the globe. As the PA reaches the end of the road, can the Palestinian people find ways to revive and reclaim a democratically structured PLO and its narrative of liberation, drawing on what was once its capacity for learning, strategic thinking, and alliance building in the Arab world and beyond?

Al-Shabaka Policy Advisor Jamil Hilal is an independent Palestinian sociologist and writer, and has published many books and numerous articles on Palestinian society, the Arab-Israeli Conflict, and Middle East issues. Hilal has held, and holds, associate senior research fellowship at a number of Palestinian research institutions. His recent publications include works on poverty, Palestinian political parties, and the political system after Oslo. He edited Where Now for Palestine: The Demise of the Two-State Solution (Z Books, 2007), and with Ilan Pappe edited Across the Wall (I.B. Tauris, 2010).

Notes:

- This piece is part of Al-Shabaka’s Policy Circle on Palestinian Leadership and Accountability. An Al-Shabaka policy circle is a specific methodology to engage a group of analysts in longer-term study and reflection on an issue of key importance to the Palestinian people. ?

- The unified leadership brought together the leaders of political groups including those representing semi-feudal and traditional religious leaders. See Jamil Hilal, The Formation of the Palestinian Elite: From the Emergence of the Palestinian National Movement until after the Establishment the Palestinian Authority (in Arabic), Muwatin, 2002. ?

- For a vivid and compelling account of Palestinian life and society before 1948 see Walid Khalidi, Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians 1876-1948, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1985. ?

- Reconstruction of Palestine, published by the Palestine Anti-Zionism Society, The Syrian American Press, New York City, 1919. ?

- The faction called itself Fatah al-Intifada and was supported by the Syrian and Libyan regimes at the time. ?

Please Contribute to Consortium

News on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

The issue of the origins of the absence of a Palestinian state is comprised of two themes. Zionist aggression and a preexisting inability of the Palestinians to form a state. A modern state is not created by a declaration of progressive political leaders. It is created by the people themselves, a modern state is also a new thing in history, Europe did not achieve them until the 1700s. Palestinians and Arabs have not maintained the progress they have achieved they have slipped into sectarianism and have not overcome tribalism. people identify with tribes and sects instead of nation states and until this is resolved there will not be a modern state. Israel is a curious counter example because it is a tribal/sectarian state that by appearances is modern, but such modernity is due to have a large ‘tribe’ and sectarianism that is open to secularism and atheism. But Israel is on the path backward because it is becoming more religious. It is not the anti-Zionist movement that will end Israel but the Haredi.

Vietnam was able to resist U.S imperialism because it consolidated its sectarianism, went to war against the tribes supporting U.S imperialism and from that forged the consciousness of people ready to create a modern nation state.