Three scholars look at what can be done for U.S. farms, where bankruptcies were already at a 10-year high before the floods this past spring.

By Maywa Montenegro, University of California, Davis; Annie Shattuck, University of California, Berkeley, and Joshua Sbicca, Colorado State University

These are difficult times in farm country. Historic spring rains – 600 percent above average in some places – inundated fields and homes. The U.S. Department of Agriculture predicts that this year’s corn and soybean crops will be the smallest in four years, due partly to delayed planting.

Even before the floods, farm bankruptcies were already at a 10-year high. In 2018 less than half of U.S. growers made any income from their farms, and median farm income dipped to negative $1,553 – that is, a net loss.

At the same time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that about 12 years remain to rein in global greenhouse gas emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Beyond this point, scientists predict significantly higher risks of drought, floods and extreme heat.

And a landmark UN report released in May warns that roughly 1 million species are now threatened with extinction. This includes pollinators that provide $235 billion to $577 billion in annual global crop value.

As scholars who study agroecology, agrarian change and food politics, we believe U.S. agriculture needs to make a systemwide shift that cuts carbon emissions, reduces vulnerability to climate chaos and prioritizes economic justice. We call this process a just transition – an idea often invoked to describe moving workers from shrinking industries like coal mining into more viable fields.

But it also applies to modern agriculture, an industry which in our view is dying – not because it isn’t producing enough, but because it is contributing to climate change and exacerbating rural problems, from income inequality to the opioid crisis.

Reconstructing rural America and dealing with climate change are both part of this process. Two elements are essential: agriculture based in principles of ecology, and economic policies that end overproduction of cheap food and reestablish fair prices for farmers.

Climate Solutions on the Farm

Agriculture generates about 9 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from sources that include synthetic fertilizers and intensive livestock operations. These emissions can be significantly curbed through adopting methods of agroecology, a science that applies principles of ecology to designing sustainable food systems.

Agroecological practices include replacing fossil-fuel-based inputs like fertilizer with a range of diverse plants, animals, fungi, insects and soil organisms. By mimicking ecological interactions, biodiversity produces both food and renewable ecosystem services, such as soil nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration.

Cover crops are a good example. Farmers grow cover crops like legumes, rye and alfalfa to reduce soil erosion, improve water retention and add nitrogen to the soil, thereby curbing fertilizer use. When these crops decay, they store carbon – typically about 1 to 1.5 tons of carbon dioxide per 2.47 acres per year.

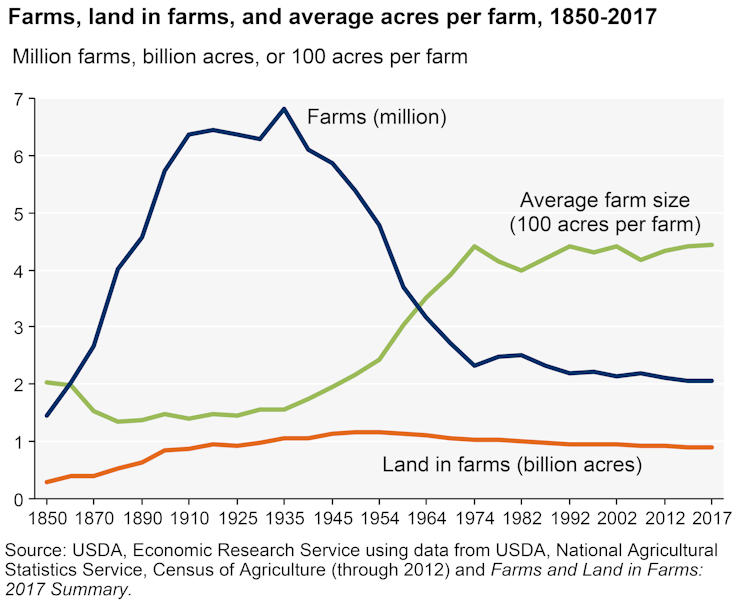

Cover crop acreage has surged in recent years, from 10.3 million acres in 2012 to 15.4 million acres in 2017. But this is a tiny fraction of the roughly 900 million acres of farmed land in the U.S.

Another strategy is switching from row crops to agroforestry, which combines trees, livestock and crops in a single field. This approach can increase soil carbon storage by up to 34 percent. And moving animals from large-scale livestock farms back onto crop farms can turn waste into nutrient inputs.

Unfortunately, many U.S. farmers are stuck in industrial production. A 2016 study by an international expert panel identified eight key “lock-ins,” or mechanisms, that reinforce the large-scale model. They include consumer expectations of cheap food, export-oriented trade, and most importantly, concentration of power in the global food and agricultural sector.

Because these lock-ins create a deeply entrenched system, revitalizing rural America and decarbonizing agriculture require addressing systemwide issues of politics and power. We believe a strong starting point is connecting ecological practices to economic policy, especially price parity – the principle that farmers ought to be fairly compensated, in line with their production costs.

Economic Justice on the Farm

If the concept of parity sounds quaint, that’s because it is. Farmers first achieved something like parity in 1910-1914, just before America entered World War I. During the war U.S. agriculture prospered, financing flowed and land speculation was rampant.

Those bubbles burst with the end of the war. As crop prices fell below the cost of production, farmers began going broke in a prelude to the Great Depression. Unsurprisingly, they tried to produce more food to get out of debt, even as prices collapsed.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal included programs that directed public investments to rural communities and restored “parity.” The federal government established price floors, bought up surplus commodities and stored them in reserve. It also paid farmers to reduce production of basic crops, and established programs to prevent destructive farming practices that had contributed to the Dust Bowl.

These policies provided much-needed relief for indebted farmers. In the “parity years,” from 1941 to 1953, the floor price was set at 90 percent of parity, and the prices farmers received averaged 100 percent of parity. As a result, purchasers of commodities paid the actual production costs.

But after World War II, agribusiness interests systematically dismantled the supply management system. They included global grain trading companies Archer Daniels Midland and Cargill and the American Farm Bureau Federation, which serves primarily large-scale farmers.

These organizations found support from federal officials, particularly Earl Butz, who served as secretary of agriculture from 1971 to 1976. Butz believed strongly in free markets and viewed federal policy as a lever to maximize output instead of constraining it. Under his watch, prices were allowed to fall – benefiting corporate purchasers – and parity was replaced by federal payments to supplement farmers’ incomes.

The resulting lock-in to this economic model progressively strengthened in the following decades, creating what many scientific assessments now recognize as a global food system that is unsustainable for farmers, eaters and the planet.

A New ‘New Deal’ for Agriculture

Today the idea of restoring parity and reducing corporate power in agriculture is resurging. Several 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have included it in their agriculture positions and legislation. Think tanks are proposing to empower family farms. Dairy delegates to the regulation-averse Wisconsin Farm Bureau Foundation voted in December 2018 to discuss supply management.

Along with other scholars, we have urged Congress to use the proposed Green New Deal to promote a just transition in agriculture. We see this as an opportunity to restore wealth to rural America in all of its diversity – particularly to communities of color who have been systematically excluded for decades from benefits available to white farmers.

This year’s biblical floods in the Midwest make any kind of farming look daunting. However, we believe that if policymakers can envision a contemporary version of ideas in the original New Deal, a climate-friendly and socially just American agriculture is within reach.

Maywa Montenegro, UC President’s postdoctoral fellow, University of California, Davis; Annie Shattuck, Ph.D candidate, University of California, Berkeley, and Joshua Sbicca, assistant professor of sociology, Colorado State University. All three authors belong to the American Association of Geographers, a funding partner of The Conversation.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive language toward other commenters or our writers will be removed.

The Green “new deal” is the exact opposite of the real New Deal. GND serves the bankers and maximizes debt, and puts all resources into “removing carbon”, which is not the cause of unusual weather.

Well you lost me when I read, “We call this process a just transition – an idea often invoked to describe moving workers from shrinking industries like coal mining into more viable fields. But it also applies to modern agriculture, an industry which in our view is dying – not because it isn’t producing enough, but because it is contributing to climate change and exacerbating rural problems, from income inequality to the opioid crisis.

I was stuck on how does this solve the opioid crisis? I was thinking that a more cogent argument would not include the argument that the crisis that farmers faced was somehow fueling the opioid crisis.

Then I got stuck on, “revitalizing rural America and decarbonizing agriculture require addressing systemwide issues of politics and power. We believe a strong starting point is connecting ecological practices to economic policy, especially price parity – the principle that farmers ought to be fairly compensated, in line with their production costs.” I was thinking how does addressing system wide issues of politics and power which is a large bucket (a very large bucket), connect ecological practices to economic policy, especially price parity – the principle that farmers ought to be fairly compensated, in line with their production costs. What is actionable here?

Then I was also lost by the following: “Along with other scholars, we have urged Congress to use the proposed Green New Deal to promote a just transition in agriculture. We see this as an opportunity to restore wealth to rural America in all of its diversity – particularly to communities of color who have been systematically excluded for decades from benefits available to white farmers.” I asked myself is there a systematic exclusion to deny farmers of color from the benefits afforded to white farmers and is this problem larger than the imagined restoration of wealth for farmers of all colors based on decades of supporting corporate agribusiness at the expense of smaller farmers no matter their ethnicity?

If I was an editor I would send this back to the writers with a lot of questions and data to support these conclusions.

1. What is the proposed mechanism which is economically viable to achieve the goal of moving workers from shrinking industries like coal mining into more viable fields like farming.

2. How is modern agricultural practice contributing to the opioid crisis?

3. What mechanism are you proposing that has sound economic principles or sound and compelling ethical principles that can address system wide issues of politics and power that connect ecological practices to economic policy, especially price parity – the principle that farmers ought to be fairly compensated, in line with their production costs.

4. What are the actions that you can propose that will decouple farm prices from free market policies and which will make economic sense to the drivers of the global economy to want to choose to support parity and guaranteed returns on farmers investments? Or what government regulations do you support to regulate global investment in agribusiness that will resonate with large agribusinesses to entice them to support parity for small farmers and ethnically diverse farmers based on those classifications?

5. What plan can convince policymakers to envision a contemporary version of ideas in the original New Deal, a climate-friendly and socially just American agriculture is within reach?

Policymakers have been on a campaign to bust farmers and turn their assets into assets owned by big agribusiness for decades and there are huge corporate lobby groups that continue to value mass production efficiencies and mass production at low cost which drive the market. Economies of scale and efficiencies of mass production along with a government fully aligned on the concepts of a global free economy are headwinds which dwarf any notion that a return to the days of the New Deal can somehow magically stop the trends based in market forces on a global scale.

It’s not that I like any of these trends and we buy produce locally at every opportunity and support our local economy at every purchasing opportunity we get. We love supporting our local producers all of which are small family owned operations. I hate the notion that one day they might be gone and our only chance to purchase fresh food is from some giant agribusiness.

However the arguments for providing a solution to the problem of giant agribusiness overrunning small farmers by somehow enlightening our government which is squarely focused on subsidizing big business and letting the little guy fail for the benefit of giant corporations seems to be entrenched in our lobby filled government where the guy with the biggest wallet calls the shots.

I’m asking what can realistically be done? To me the article seems like pie in the sky theorizing not grounded in the economic realities of our current economy and without realistic solutions except to somehow return to the much hated and reviled New Deal which not only manifests itself in the ignoring of the plight of the little farmer but also in turning a deaf ear on all of society here in America that is not a member of the profiteering class of corporate entities which by now have captured our government turning it from a body that acts in the public interest into a body that is only concerned with corporate interests.

That is a larger picture of what we are dealing with. What we are all dealing with. Pharmaceutical prices are skyrocketing. Insurance rates are skyrocketing, Health Care is skyrocketing leaving American Citizens in the same economic vise as small farmers. Wages are stagnating while the Stock Market rises. More people are left with a subsistence wage often working multiple jobs to meet the bills that come in the mailbox from corporations that are raking in record profits while returning diminishing services as a return for the services they provide.

Despite this there is no general call from the population to end the price gouging. There is no public demand for more efficient and less expensive goods and services. There is no effective counter push from consumers which might provide an incentive to curb high prices for goods.

Instead what we see is an economy that is increasingly geared to make its profits from people who do not object to exorbitant prices and are enticed to spend every last dollar they make on things that are not as essential as food to eat. The problem is that this is working against building parity for the major stratus’s of income earners. For the majority they submit to rising prices, diminishing returns on their purchases, loss of equity and an increasing debt based economy that is fueled by easy credit and huge profits by banks from the interest on debt. It reminds me of Pinocchio when he is enticed to go with his con artists to Money Island where every boy is encouraged to act as badly and as irresponsibly as they wish only to be turned into beasts of burden for the profit of those who require the services of donkeys at donkey wages. That fairly sums up where we are.

Perhaps the authors can expand their scope to include the larger economy which is the same thing that farmers face. Then they would see that the problem is not limited to farmers but applies to the majority of Americans. We are all being willing accomplices to the rise of giant businesses that seek to end competition and establish control of markets for the purposes of unfair business practices that maximize their profits by eliminating competition.

This is what is happening and an argument can be made that the results of the free market which has changed the meaning of a monopoly into the definition of a free market enterprise.

I think the small farmers in America are just one class of Americans who are “going out of business” To effectively resonate with the majority of Americans, the messaging coming from farmers needs to not only plead their case but it needs to be inclusive of all of the other facets of the economy where people just like farmers are being pushed to the edge of insolvency by special interests (corporations) which have gained almost complete control our government to the exclusion of every other small business.

Then there might be some resonance for the majority of Americans that did not grow up on farms nor do they own them.

No need for “scholars”… real practitioners already on this for over 20 years… See Will Harris, Joel Salatin, Gabe Brown, Allan Savory, et al. http://blog.whiteoakpastures.com/in-the-moment/tale-of-two-brothers

Several areas of unanswered questions:

1. It is unclear why the industry would move to small-scale farms and higher prices. The large-scale model seems able to use “sustainable farming methods” except (maybe) “agroforestry, which combines trees, livestock and crops in a single field.” Raising prices to “empower family farms” does not seem sensible. Why not regulate damaging practices (insecticides/herbicides/runoff etc) and let the lowest cost methods set the price?

2. Also not clear why 9% of CO emissions would focus attention on farming. It also causes eco-damage by clearing forest, fertilizer runoff, extinctions, etc., but all can be specifically regulated. Eco regulations should be UN enforced and funded by UN excise taxes.

3. Also we must consider the issues of international trade. Cheap food will be the primary criterion in most of the world, whatever the US does, and it will lose foreign trade if it raises costs without worldwide regulation. Lower costs elsewhere with fewer regulations requires treaties to regulate eco-damage, sustain farm pay rates elsewhere, etc. That will raise import prices, which can then be taxed by consumer states or the UN to fund foreign aid to producer states. Protectionism vs. trade involves many problems and solutions.

4. The capture of regulators by industry is a distinct problem in all industries: let’s get the money out of politics in all areas.

You all should add debt forgiveness for small farmers to your list of suggestions.

“Debts that can’t be paid, won’t be paid” – Michael Hudson

My question is, have any of these three authors spent any real world time actually running a farm with all the hard work involved?

Yes geeyp, most of these climate change enthusiasts display the same properties as a solar panel! – If you gave them a farm, they would not be able to feed themselves with it. They simply lack the skills and centuries of knowledge and experience necessary to do so.

No solar panel can generate enough power in its lifetime to mine, manufacture, transport, install, and dispose of itself.

That assertion is hardly worth a response. Solar power would obviously be many times as costly as fossil fuel power if that were so. Obviously none of these issues requires farm experience.

Farming should be a profitable occupation, as everyone needs food. Why has it not been? Something is amiss…

I wonder, though, why it takes three doctorates to write a short article? It seems the new trend. Even the shortest stories in the mainstream media often have 2 or 3 names attached….

And as usual the another site puts it’s faith in “Climate change” without the remotest clue of the carbon cycle, we contribute about 3.18% to to total CO2, or how much impact CO2 actually puts into temperature. Hint at 400 ppm and above there is almost no calculable impact until you reach around 1200 ppm, and that’s from the IPCC report. CO2 is plant food and below 280 ppm plant growth becomes impaired. Do some actual research for a change.

Mr. Details, while you don’t provide any denial references, I’ll say this much, CO2 is absolutely essential IN THE GROUND to support plant life.

Extraction of fossil at the rates industrial world has done is detrimental to life on the planet and the biosphere that supports it. As far as what humans contribute, I have no idea where you got your number. Be honest, and admit it, the truth is just intolerable for you and many others.