Exclusive: The death of Hanoi Hannah, the radio voice urging U.S. G.I.’s to turn against the Vietnam War, brought back memories of another time when propaganda often trumped truth, writes veteran war correspondent Don North.

By Don North

Her name was Trinh Thi Ngo. She called herself Thu Houng – the fragrance of Autumn. We called her Hanoi Hannah. Her job was to chill and frighten, not to charm and seduce. Her English was almost impeccable and as North Vietnam’s premier propagandist she tried to convince American G.I.’s that the war was immoral and that they should lay down their arms and go home.

Hannah: How are you G.I. Joe? It seems to me that most of you are poorly informed about the going of the war, to say nothing about a correct explanation of your presence over here. Nothing is more confused than to be ordered into a war to die or to be maimed for life without the faintest idea of what’s going on. Hanoi Hannah June 1967.

Trinh Thi Ngo, known as “Hanoi Hannah” who broadcast English-language propaganda to U.S. G.I.’s during the Vietnam War. Photographed after the war, in 1978, by Don North)

The wartime words of Hanoi Hannah, part of the loud soundtrack for the Vietnam War, which may have been the first war fought to a rock n’ roll background, but for American G.I.’s along with the beat came the message: propaganda from North Vietnam’s radio beamed south or misinformation from the U.S. Army radio in Saigon. Even so, radio brought music with a familiar sound to soldiers who thought the war was the end of the world, and to many it didn’t matter who was broadcasting: the Voice of Vietnam or U.S. Armed Forces Radio.

Trinh Thi Ngo’s death on Sept. 30 at the age of 87 brought back a flood of memories from my days as a young war correspondent covering the Vietnam War. I not only listened to Hanoi Hannah during the war, I got to interview her after the war.

Trinh was born in Hanoi in 1931. Her father owned the largest glass factory in Vietnam. She took a liking to American films. Her favorite was Gone With The Wind, which she watched five times. She wanted to enjoy American films without the French or Vietnamese subtitles, so her family gave her private English lessons.

She joined Voice of Vietnam (VOV) in 1955 as a volunteer. Her unaccented English, her correct intonation and her large vocabulary soon got her a staff job reading the news to Asia’s English-speaking countries. One of her tutors at the station was the Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett.

When the first American ground forces, the U.S. Marines, landed at Danang in 1965, VOV decided to start propaganda broadcasts to the troops as they had done for the French. Hannah’s scripts were written by North Vietnam Army propaganda experts, advised by Cubans. Her programs were extended to 30 minutes and broadcast three times a day.

Arguably, Hanoi Hannah broke one of the most shocking news stories of the Vietnam War, the massacre of several hundred Vietnamese civilians in the village of My Lai. Just weeks after the massacre on March 16, 1968, Hanoi Hannah, in one of her broadcasts, accurately named the location and estimated the civilian death toll, but she misidentified the U.S. Army division involved, enabling the U.S. command to deny the report and treat it like another example of disinformation from North Vietnam.

The atrocity would take more than a year to be confirmed, following efforts by Americal Division veteran Ron Ridenhour, who had heard rumors about the massacre and interviewed fellow Americal vets before alerting members of Congress. In November 1969, the story was brought to the public’s attention by investigative journalist Seymour Hersh reporting for Dispatch News, a disclosure that intensified domestic opposition to the war.

Hannah and Beer

I first heard the silken voice of Hanoi Hannah in a U.S. Special Forces base at An Lac, about a hundred miles west of Nha Trang. I had been on patrol with Montagnard Irregulars and their American advisers. It had been raining hard for a week keeping the supply plane that was my ticket out from coming in. At night after the perimeter was secured, there wasn’t much to do but play cards, read, drink Ba Moi Ba beer and listen to the radio. Up in the Central Highlands the Voice of Vietnam boomed in loud and clear.

Hanna: We gotta get out of this place, if it’s the last thing we ever do. We gotta get out of this place, surely there’s a better place for me and you. The Animals. Now for the war news. American casualties in Vietnam. Army Corporal Larry J. Samples, Canada, Alabama … Staff Sergeant Charles R. Miller, Tucson, Arizona … Sergeant Frank Hererra, Coolidge, Arizona. Hanoi Hannah, Sept. 15, 1965

Her broadcasts were mostly exaggerated war news, encouragement to frag an officer and go AWOL or suggestions that the soldiers wives or girlfriends at home were cheating on them. She was mostly greeted with loud laughs and often beer cans thrown at the radio. But taped interviews with downed U.S. pilots or from American anti-war advocates like Jane Fonda were heard with anger.

The Voice of Vietnam broadcasts, while mostly funny at the time, tended to stay with you like a Ba Moi Ba headache in the morning.

PsyOps: Winning Hearts and Minds

By 1965 the airwaves over North and South Vietnam had become a confusing battleground of conflicting propaganda voices. Working on the premise of “capture their hearts and minds and their hearts and souls will follow,” both sides supported dozens of radio stations spewing malice and disinformation 24 hours a day.

ABC News correspondent Don North in May 1967 with the U.S. Army on Operation Junction City in Vietnam.

The American Voice of America with transmitters in Hue and the Philippines was one of the most powerful voices, rivalling the Voice of Vietnam. It is estimated the CIA ran 11 clandestine broadcasts of “black” or “false flag” radio like Red Star allegedly run by communist defectors. The American Studies and Observation Group (SOG) ran a broadcast with a fake Hanoi Hannah, while the South Vietnamese regime ran Mother of Vietnam radio with host Mai Lan, a South Vietnamese with a seductive voice who had studied broadcasting in the U.S.

All these stations knew that the first rule of propaganda broadcasting was to “know and understand your target audience.” It was recognized that if used properly the spoken word could be a powerful inspiration and motivator although most of the propagandists were not very effective in delivering the message.

My friend Thuc Pham from Hanoi explained to me the main reason both North and South broadcasts failed in their goal. “People were very poor, both sides distributed transistor radios tuned to the stations, but most Vietnamese during the war could not afford batteries. The North Vietnam government also forbid citizens to listen to foreign broadcasts and punished those who did.”

Women Broadcasters of Propaganda

Hanoi Hannah followed a line of women broadcasting propaganda to their mostly male audiences. They often had a history of failure.

Axis Sally: British and American troops on the march in Italy in World War II heard the voice of Rita Zucca, who was born in New York. She first broadcast for Mussolini’s fascist government and later for Nazi Germany. Based in Rome, she hosted Jerry’s Front. Her signature sign on was “Hello Suckers! Sally was captured by U.S. forces in February 1943 and convicted of collaboration with the enemy.

Tokyo Rose: Born in Los Angeles in 1916, a Nisei first generation American. She was visiting Japan when war broke out in 1941 and forced to broadcast for the Japanese. In her daily program, The Zero Hour, she would predict attacks, identify American ships and play American music while speaking American slang. After the war she was arrested by U.S authorities, convicted of treason and imprisoned until 1956. Some two decades later, she received a pardon from President Gerald Ford.

Seoul City Sue: During the Korean war, Anna Wallis, a Methodist missionary from Arkansas, was the North Korean radio voice in 1950. Her programs named American soldiers captured or killed, and she threatened newly arrived soldiers. She spoke in a monotone and had little pop music to offer, so her show was not popular. In 1969, she was executed by the North Korean Army, suspected of being a South Korean agent.

Baghdad Betty: In September 1990 soon after the arrival in Saudi Arabia of the U.S. 82nd Airborne, Iraq’s Voice of Peace began broadcasting with an English-speaking Iraqi woman. Americans named her Baghdad Betty. She played pop music more popular than the religious music on Saudi stations, but to bolster their own forces and influence Arab allies, she bad-mouthed American troops saying they drank liquor and defiled the holy places of Islam. Her propaganda writers had a jaundiced view of American culture.

Betty was often humorous, but mostly absurd. She is alleged to have said, “American soldiers, while you are here your wives and girlfriends are making love to Tom Cruise, Robert Redford and Bart Simpson.” If true, her comment was typical of her misinformed message, but the words may have originated with American psy-ops specialists to mock and discredit her.

Covering preparations for war in the Saudi desert, I heard some of her broadcasts. She was no Hanoi Hannah, who was far more skilled and polished.

Col. Jeff Jones, chief of the U.S. Army’s 8th Psychological Task Force, told me Betty’s broadcasts just made our troops laugh: “Her broadcasts proved the Iraqi’s didn’t understand us at all. Her ignorance was pervasive. She was never sure of her sources and broadcast dated news.” Saddam Hussien wasn’t impressed either and fired her after three months.

Hanoi Hannah: American G.I.’s don’t fight this unjust, immoral and illegal war of Johnson’s. Get out of Vietnam now while you’re still alive. This is the Voice of Vietnam. Now here’s Connie Francis singing “I almost lost my mind.” August. 1967.

For almost five years, after I became a radio and TV correspondent for ABC News, I would tape-record her programs most days in case she said something newsworthy or presented a captured American pilot on her program. It was just another source of information or disinformation to be checked out and sorted out in the communications pudding of the Vietnam War.

But for bored G.I.’s her broadcasts were often rare sources of amusement. The G.I’s radio was, after their rifle, a most valued possession. Like the rifle butt, the radio was often wrapped in frayed black tape for protection. Troops would laugh over Hanna’s attempts to scare them into defection or suggestions to frag an officer. If their unit was mentioned, a great cheer went up and they pelted the radios with empty beer cans. Although virtually no one took her seriously, they did wonder if she was as lovely as she sounded, and many considered her the most prominent enemy after Ho Chi Minh.

Hannah’s broadcasts to American troops lasted eight years, ending in 1973 after most U.S. troops left for home. However, on April 30, 1975, she was the first person in the world to break the news: “Saigon is liberated. Vietnam is completely independent and unified.”

Post-War Life

In May 1978, I returned to Vietnam and requested the Foreign Ministry arrange an interview for me with Trinh Thi Ngo. By then, Hanoi Hannah had left her beloved Hanoi and moved to Ho Chi Minh City, the renamed city of Saigon, with her husband who was a southerner and Vietnamese Army officer.

Trinh Thi Ngo, the Vietnam War’s “Hanoi Hannah” during an interview with Don North on the Rex Hotel rooftop bar in Ho Chi Minh City (or Saigon) in 1978. (Photo credit: Don North)

The appointment was set up for the rooftop bar of the Rex Hotel, where I waited along with Ken Watkins, 31, a Vietnam veteran from Houston, Texas, who had been a Corpsman with the First U.S. Marines and a regular listener to Hannah. While waiting, Ken recalled his memories of Hanoi Hannah: “The signal was pretty good around Danang and we would tune in once or twice a week to hear her talk about the war. U.S. Armed Forces radio didn’t talk about the war or attitudes at home.

“Hannah didn’t necessarily make sense, she used American English, but really didn’t speak our language in spite of hip expressions and hit tunes, even tunes banned on U.S.

Army radio. The best thing going for her was that she was female and had a nice soft voice. Whenever she named our unit, the First Marines, and where we were, that always stands out in my mind. Some of us thought she had spies everywhere or a crystal ball.”

I asked, “Ken, do you still feel any anger toward her?”

“Sure some antagonism, add it to the Vietnam list. But this trip back is about coming full circle on a lot of things and she is another voice from the past I want to confront in person.”

So a ex-Marine and a former Vietnam war correspondent waited that sunny morning for the real Hanoi Hannah to appear, waiting for reality to sweep away years of bitter images in the windmills of our minds.

Dragon Lady? Prophet? Psy-warrior? Or what? Like so many of the phantoms from the war she was not what she seemed. She was no phantom. She didn’t look like the Dragon Lady from “Terry and the Pirates” comics. Elegant and attractive in a striking yellow Ao Dai, the Vietnamese traditional dress, she appeared happy to answer questions.

I asked: “Many American soldiers think you received excellent intelligence on their units, battle-readiness and casualties. What was the main source of your information?”

Hannah: “U.S. Army Stars and Stripes. We read from it. We had it flown in every day. We also read Newsweek, Time and several newspapers. We took remarks of American journalists and put them in our broadcasts, especially about casualties … high casualties.”

“Do you remember any articles in particular that you used?”

Hannah: “Yes, Arnaud De Borchegrave in Newsweek. I remember we used his articles. Americans are xenophobic, they will believe their own people rather than the adversary. And Don Luce about the tiger cages. We would often say to the G.I.’s that the Saigon regime was not worth their support.”

“Did you ever feel anger toward American soldiers?”

Hannah: “When the bombs came on Hanoi, I did feel angry. During the 1972 Christmas bombing, our broadcasting was moved to a remote area outside the city. To the Vietnamese, Hanoi is sacred ground. But even then, when I spoke to the G.I.’s I tried always to be calm, I never felt aggression toward Americans as a people. I never called them the enemy, only adversaries.”

June 1967

Hannah: “Now for our talk. A Vietnam black GI who refuses to be a victim of racism is Billy Smith. It seems on the morning of March 15th a fragmentation grenade went off in an officer’s barracks in Bien Hoa killing two gung-ho Lieutenants. Smith was illegally searched, arrested and put in Long Binh jail and brought home for trial. The evidence that showed him guilty was this: being black, poor and against the war and refusing to be a victim of racism.”

Air Force F-105s bomb a target in the southern panhandle of North Vietnam on June 14, 1966. (Photo credit: U.S. Air Force)”

Mike Roberts, 41, Detroit, Michigan remembers Hannah. Based in Danang through 1967 and 1968, Roberts summed up his recollections of the black veterans attitude toward Hannah’s broadcasts: “I remember June 1968. I was sitting in a tent with guys from Charlie company and we were gambling, drinking and having a good time and listenin’ to the radio. One guy says ‘Sshh, sshh, be quiet’ and he says ‘There’s a riot in Detroit.’

There was no feeling of what were they rioting for? We all knew what they wanted, you know what I’m sayin’? So of course we would feel empathy for the folks back home.

“Then Hannah comes on and she knows what guard unit was called in and what kind of weapons were used … you know what I’m sayin’. That’s when it starts to hit home. We knew what kind of fire power and devastation that kind of weapon can do to people, and now those same weapons were turning on us, you know, our own military is killing our own people.

“We might as well have been Viet Cong. But Hannah picked up on it and talked about it. And clearly if she knew about it, Armed Forces radio did too. That was the first time I started hearing Hannah call upon Blacks, you know, to rethink the situation here. Why are you fighting? You have your own battle to fight in America. We were smokin’ herbs, you know and we decided to listen to Hanoi Hannah.”

Jim Maciolek, U.S. Army First Division, Lai Khe, 1966:“When we heard Hannah mention our unit we would give a cheer and throw our beer cans at the radio. If she knew where we were, so did everybody else. But U.S. Armed Forces was on constantly, too. So we heard what they wanted us to hear. I would have liked to hear about opposition to the war that was being staged back home. That way I would have been better prepared when I got back home … seeing hippies, people chanting slogans against the war, people with black arm bands … that was all new to me.”

By zapping the truth through a censorship policy of deletions and by allowing in the exaggerations of propaganda, U.S. Armed Forces radio lost the trust of many American soldiers in Vietnam when they were most isolated and vulnerable to enemy propaganda.

It wasn’t that Hanoi Hannah always told the truth; she didn’t. But she was most effective when she did tell the truth and U.S. Armed Forces radio was fudging it. If we didn’t know before, the Vietnam War should have taught us that communications are now so pervasive in this shrinking world that suppression of information is impossible. Accuracy and honesty is essential, not just because it’s morally right but because it’s practical too.

A Captive Audience

Hanoi Hannah could always be assured of at least the American prisoner of war (POW) audience “authorized” to hear her broadcast in prisons like the Hanoi Hilton.

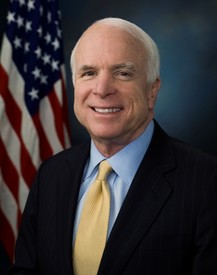

Sen. John McCain, a Hanoi Hilton inmate for over five years, recently remarked: “I heard Hannah every day. She was a marvelous entertainer. I’m surprised she didn’t get to Hollywood.”

Lt. Commander Ray Voden of McLean, Virginia, shot down over Hanoi on April 3, 1965, endured her broadcasts for eight years: “Hannah’s broadcasts often stirred up arguments among the POW’s. There were nearly fist fights over the program. Some guys wanted to hear it, while others tried to ignore it. Personally, I listened because I usually gleaned information, reading between the lines. She always exaggerated our aircraft losses, often claiming hundreds of our planes shot down when we hadn’t heard anti-aircraft fire in weeks.

“Music was the best part of it. Sometimes playing American tunes that were supposed to make us homesick had the opposite effect. One time they played ‘Downtown’ by Petula Clark and everyone started dancing and yelling for an hour, just went wild. Another one that gave us a hoot was ‘Don’t Fence Me In.’

“I’ve no hatred for her now. She was doing her job and I was doing mine. But no, I wouldn’t go out of my way to meet her today if given a chance.”

In our interview in 1978, I asked Hannah, “Did you ever evaluate the effects of your broadcasts?”

Hannah: “No, during the war it was difficult to get feedback except through foreign news reports but we knew we were being heard.”

“What were your main aims?”

Hannah: “We mentioned that G.I.’s should go AWOL and suggested some frigging, or is that fragging. We advised them to do what they think proper against the war.”

“I don’t know of a single fragging case after your suggestion, and there were few, if any defections, did that surprise you?”

Hannah: “No, we just continued our work. I believed in it. I put my heart in my work.”

“If you could make a final broadcast to American G.I.’s today, what would you say?”

Hannah: “Let’s let bygones, be bygones. Let’s move on and be friends. There will be many benefits if we can be friends together. There is no reason to be enemies.”

Meeting and interviewing Hanoi Hannah was, for me, like being Dorothy parting the curtains hiding the Wizard of Oz. The terrible Hannah behind the façade that we constructed, turned out to be a mild-mannered announcer who spoke English and read the Stars and Stripes.

After her death on Sept. 30, Madam Trinh Thi Ngo was interred in Long Tri, Chau Than District, Long An province, following the Vietnamese custom of burial next to her husband and his family.

Her only son escaped Vietnam in 1973 with the boat-people exodus and now lives in San Francisco.

Don North is a veteran war correspondent who covered the Vietnam War and many other conflicts around the world. He is the author of Inappropriate Conduct, the story of a World War II correspondent whose career was crushed by the intrigue he uncovered.

We prefer not to use the patronizing term “propaganda” when describing aspects of national liberation struggles against imperialism.

Bernays, the founder of modern mass marketing, had this to say on the subject in his 1928 classic book “Propaganda”, “[w]e are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society…They govern us by their qualities of natural leadership, their ability to supply needed ideas and by their key position in the social structure. Whatever attitude one chooses to take toward this condition, it remains a fact that in almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons—a trifling fraction of our hundred and twenty million—who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”

Mother Vietnam was not run by the South Vietnam Government. SOG, under CIA control, ran it and it was not started until after the 1973 cease-fire. Mother Vietnam was one of five CIA radio stations run out of the same address, 7 Hong Tap Tu, Saigon(each on a different frequency of course). Two were Cambodian language. In Vietnamese were Mother Vietnam, Sacred Sword, and Southern Nam Bo. “House 7”, as the CIA boys called it had 144 Vietnamese employees, besides SOG Americans and Bill Johnson and his CIA boys. Don North sounds as obsessed with Mai Lon as Bill Johnson was(and she was a classy thoroughly Americanized babe) but she was one of at least two female voices of Mother Vietnam. I do not know what the two Cambodian language stations or Southern Nam Bo gimmicks were, but Sacred Sword posed as a non-NLF revolutionary group(the Sacred Sword is a powerful Vietnamese patriotic story from the Ming invasion). Mother Vietnam was directed at the NVA trooper, and tried to undermine morale by using sentimental content to produce a feeling that “all Vietnamese were one”. A naive stratagem to reduce NVA will to fight as reunification of the country was Hanoi’s stated goal(it was Saigon that sought to keep Vietnam divided, a losing position) and the Vietnamese are ultra-ethnocentric(to the point they will treat a Vietnamese-American like a foreign tourist). House 7 was an expensive, useless joke, merely “very light duty” fun-n-games for the SOG boys.

I agree with some of the comments above. I was expecting that at some point in his article, Mr. North would admit that Hanoi Hanna’s “propaganda” turned out to be pretty close to the truth. But I was wrong, he seems to be still clueless about why were half a million US soldiers sent to Vietnam over ten years, and why the GI’s killed about three million Vietnamese people.

Thanks for this

I have returned to Viet Nam about thirty times. My latest trip back involved going to Dien Bien Phu.

I had an excellent guide and interpreter

I hope to return again in a few months, maybe for Tet holiday

if you are interested in joining us, email me at meissnerjoseph@yahoo.com

Have you been to the Can Tho area recently? It was a bit messy when I was there in ’72, was thinking of seeing how it is now. Gonna be too old to travel much soon :(

“She tried to convince American GIs that the war was immoral and that they should lay down their arms and go home.”

Just a tiny historical note: She was correct. The “propaganda” was correct.

If her message, the “propaganda”, was heeded it only would’ve saved millions of lives. No big whoop.

Every day in my American life I am subject to propaganda. The propagandist are MSNBC, FOX, and CNN, the New York Times, the Washington Post, etc., etc. Are these news outlets guilty of aiding in our war hungry leaders war crimes? Yes. Will they ever be prosecuted for aiding in these dastardly evil war crimes? Probably not. The way I see it, you have two choices. Either you seek out the real honest truth of our geopolitical world, or you watch reruns of the Kardashians, and act stupid and surprised when the world blows itself up. No one ever said that spreading democracy, liberty, and freedom was going to be easy. So buckle up citizen, the fun is only beginning to begin…Madam President will lead us forward, and her trustworthy MSM will be sure to follow her every step along the way.

Hannah: “Let’s let bygones, be bygones. Let’s move on and be friends. There will be many benefits if we can be friends together. There is no reason to be enemies.”

She might have added, “Help clean up the environmental disasters created during the war and provide health care to its victims.”

ACHTUNG!!!MINEN!!!! Go to Vietnam where these signs warn of still active minefields laid by The US Army and Marines. The Pentagon “refused” to give the Vietnamese Government “sapper’s maps” of American minefields showing the location of the mines(used by sappers when clearing a field). Ah Yes, Let Bygones Be Bygones!!! And since Don North can’t seen to “move on and be friends” let’s send him back to Vietnam one last time, with a stick, that he can use to “clear” a few mines. How about it Don, feel like a trip????

At a meeting sponsored to ban landmines, a speaker asked how many landmines would it take to scare farmers from working their fields. Easy answer: One. Wrong: None. Just the fear of a mine will do it.

Bill you probably are up on this, but I do believe that Nixon promised the Vietnamese 3.5. billion dollars in reparations. Nixon’s offer was shrewd for the fact that Nixon knew Congress would never approve that reparation payment, and by then the war would have ended. Not only did the Vietnamese people suffer with Nixon’s con job, but so did the many left behind American POW’s who never gained their freedom, since they were the bargaining chip.

Joe Tedesksy, there were zero American POW’s retained by Vietnam. That putrid lie is promoted to this day by, among others, The Unz Review. This lie has two parts. One a murky narrative composed of arch implications unsupported by facts, two conflation of MIA’s and deserters as POWs. To this day there are American deserters living in Viet Nam, very hush-hush in USA, waiting for them to die. A Canadian journalist followed one story a few years back. Went to the village, the Party Cadre said “yeah, we know about that guy”. An old man now, living with his Vietnamese wife. He was SOG, on a classified mission “behind the lines”, wounded his future wife nursed him. He had a wife and children in the States he never returned to. Never gonna be a movie about that guy, just crap like “Deerhunter”. Maybe Don North might do a peice??? Naaah, Don is too busy smearing and lying. I noticed the humanity Trinh Thi Ngo showed in contrast to the petty-satanic dishonest sneering of Don North. Maybe that’s why that SOG-dude decided to destroy his uniform and become Vietnamese.

Strange that Don would ask if someone held a grudge against Hanoi Hannah.

Vietnam never threatened or attacked America. America invaded Vietnam , killed over 2 million people in SE Asia, all based on BS.

The people of SE Asia have millions of reasons to hold a grudge against America.

I was never in the military. Having graduated from high school in 1969, I went to college (before dropping out) and had a college

deferment, until they did away with them. The lottery was implemented shortly after that. The first year I had a “high number” and

the second year, Nixon got us out of Viet Nam – the only worthwhile thing that he probably ever did. My thought was that if I was

going to get called up, I’d march down to either the navy or Air Force recruiter- only to maximize my chances of coming back alive.

Having learned what I’ve learned about the REAL history of our country, I’m very glad that I was never in the military. What was

the war in Viet Nam for anyway? So that 50,000+ Americans could lose their lives and so that they could have sweat-shop

factories for Nike and other tennis shoe manufacturers? Pretty sad…

By the way, I did join Viet Nam Veterans Against The War, even though I’m not a veteran. I’m now very much anti-war and anti-

banksters, anti-CIA and a lot of other “anti’s.”

I and two other boot campers volunteered for Vietnam until my Boot Camp DI pulled the three of us in our company aside as he erased our standing up to serve in Vietnam telling us to pick another duty station, and then he told us three recruits how he had served two tours of duty in Vietnam, and how our country wasn’t fighting to win anything, and he wasn’t going to be apart of anything to send us off to die for a no reason, no solution war. Crazy, I know. I lost friends, and some came back not in the shape they were in when they left. That was in 1968. There was nothing right about that war, or any of these ‘conflicts’ our government seems to like to stay busy with. We older dudes who served, didn’t serve, burned they’re draft cards and played harmonica…..anybody, we should all band together, and call for an end to all this U.S. Instigated wars.

This whole geopolitical strategy the U.S. is taking, is all based on military might. There will probably not be a nuclear war, unless someone or someone’s are very crazed nuts to follow through with it.

China is now finding more and more nations willing to get involved in the ‘Silk Road’ projects. Catapillar has been in decline for over three years. If America would put a quarter of what in puts into the DOD an do it’s own Silk Road, then the ‘positive’ benefits of such a program would bear fruit for another fifty to one hundred years. Do you have any idea how many replacement parts you would sell to a Catapillar machine, which may run in service for the next fifteen years, or longer. How much repeat business to you get from a bomb….and yes I know Catapillar can come later after the bomb and clean up….but the question is; is how much is to much ‘later’?

This guy sells it better than I do….

http://cluborlov.blogspot.com/2016/10/oopsa-world-war.html#more

And yet very few in Asia actually seem to hold much of a grudge against the US. Part of that might be fear of China, But I saw very little actual resentment in Vietnam or Cambodia. But many years have passed, something like 80% of the population there were born after the conflicts ended.

THANK YOU for pointing out a TRUTH that is STILL NOT SAID in the U.S> where most Americans think that the countries we bomb, the people we kill & maim, should be GRATEFUL to us “for bringing them democracy”. What the U.S> did in Vietnam it now REPEATS in the Middle east—having LEARNED NOTHING (except to end the draft–since ONLY American deaths matter & if you can keep those down, too many Americans will blindly support the Endless Wars for War-Profiteers & Multi-National Corporations)