Exclusive: Almost four decades after starring in “All the President’s Men,” Robert Redford returns portraying another famous journalist in “Truth.” But the world has been turned upside down. Mainstream media is no longer the hero exposing a corrupt president, but the villain protecting one, as James DiEugenio explains.

By James DiEugenio

In spring 2004, CBS news producer Mary Mapes was doing what journalists are supposed to do dig up facts that help the public understand important events and often make the powers-that-be squirm. She and Dan Rather, her colleague at the “60 Minutes” offspring “60 Minutes II,” had just exposed the U.S. military’s bizarre mistreatment of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison.

Documented with damning photos and direct testimony, the story revealed how U.S. military guards had stripped detainees naked and subjected them to sexual humiliations and severe physical abuse. The story forced President George W. Bush to claim that he was morally outraged by these practices and to demand that the implicated soldiers be court-martialed.

Robert Redford as CBS anchor Dan Rather in the movie “Truth” about the destruction of producer Mary Mapes and Rather over their disclosures of President George W. Bush’s neglect of his National Guard duties during the Vietnam War .

But the string that the Abu Ghraib case pulled eventually revealed that Bush and his senior advisers had authorized very similar treatment for detainees at CIA “black sites” and at Guantanamo Bay prison. In that sense, the Abu Ghraib prison story was one of the most important of the Iraq War in that it exposed the secret ugliness and grotesque criminality of Bush’s “global war on terror.”

Mapes had done other compelling stories for “60 Minutes” and its spinoff, including coverage of Karla Faye Tucker’s execution. The young woman was convicted of murder, but, in prison, became a born-again Christian and asked for a commutation from then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush. But Bush was eyeing political advancement and refused to grant it, letting her execution go forward.

In another powerful human-interest story, Mapes found the child of segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond, a child he had fathered with a black woman.

In other words, Mapes was the kind of producer who delivered hard-hitting stories that news organizations claim that they crave, the sort of reporting that not only makes for good journalism but good TV.

But Mary Mapes ran into a buzz saw of career-destroying trouble on Sept. 8, 2004, when she and her colleagues at “60 Minutes II” broadcast a segment on Bush’s spotty service in the Texas Air National Guard, the route that the Bush Family scion took to avoid the Vietnam War.

The segment posed the question of whether Bush had honored his commitment or got special dispensation to avoid a large part of his duty. Within minutes of the show being aired, actually before the hour was over, the report came under attack from right-wing bloggers who accused CBS of using forged documents as part of its presentation. The key claim of these Bush defenders was that some of the documents couldn’t have been typed in the early 1970s because IBM’s Selectric typewriters couldn’t produce superscripts (a claim that turned out to be false, since Selectric typewriters did allow for superscripts, such as the little “th” or “st” after a number).

Blaming the Messenger

Yet, caught off-guard by the ferocity of this attack and its amplification through the right-wing echo chamber and then back into the mainstream media CBS executives put Mapes on leave. Less than two weeks after the broadcast on Sept. 20, 2004 she left her office in New York, never to return.

She was told not to talk to any reporters about the segment, an order that she unwisely obeyed. She was also told by CBS News President Andrew Heyward not to do any work advancing the story. A few days later, Heyward announced the formation of a review panel. Former Attorney General Richard Thornburgh, a Bush Family apparatchik, and former Associated Press chief Lou Boccardi headed it.

In January 2005, the panel issued its report critical of some journalistic procedures that Mapes and three other producers followed in putting together the segment, but the panel could not establish definitively whether the questioned documents were indeed forgeries.

On the day Heyward read the Thornburgh-Boccardi report without letting Mapes rebut its findings he called Mapes and fired her. Three other CBS employees involved with the production producer Josh Howard, vice president of prime time news Betsy West, and executive producer Mary Murphy were asked to resign.

Dan Rather was removed from his anchor spot at CBS Evening News in March of 2005. His contract was not picked up in 2006. Thus his association with CBS ended after 44 years.

But Mapes did not go quietly. Later in 2005, she wrote a book about her career at CBS and primarily about the whole Bush/National Guard segment she produced. Truth and Duty was a spirited defense of her and her colleagues’ performance on the story.

It was also a bare-knuckled reply to the workings and verdict of the Thornburgh-Boccardi panel, a report that most of the mainstream media and the unsuspecting public accepted at face value as being the last word on the whole issue.

Because Mapes had worked in Dallas for CBS News, she had heard many tales about Texas Gov. Bush’s National Guard service, or lack of such. In 1968, after George W. Bush graduated from Yale and without a student deferment, he was eligible for a tour in Vietnam via the draft. Though the Bush clan supported the Vietnam War in public, they understood that it was not at all a cause worth risking one’s life over. So to help Bush avoid getting shipped off to Indochina, the decision was made for him to join the National Guard but not just any unit in the National Guard.

The ‘Champagne’ Unit

Young Bush would join the 147th Fighter Wing of the Texas Air National Guard (or TANG). This Houston-based unit was a haven for the rich and powerful in Texas, so much so that it was nicknamed the “Champagne Unit.” Bush went in as a Second Lieutenant, even though he had not met any of the requisite requirements to merit such an officer’s position.

The 147th also trained Bush to be a pilot. Again, this was unusual because it was rather expensive to train a pilot from scratch. The usual route was to borrow trained pilots from regular Air Force units or to train young men who had some experience, which Bush did not have.

How did George W. Bush gain entry into the TANG? The Bush family cover story was that he had talked to Lt. Col. Walter Staudt, who told him positions were open. It later turned out that it was not at all that simple. What really happened was that Ben Barnes, state Speaker of the House, used some influence to gain entry for Bush, letting him leapfrog over many other applicants. In fact, one of the scoops that Mapes got for the “60 Minutes II” segment was that Barnes went on camera to talk about what he had done.

But getting in was just the beginning of the story. Young Bush was allowed to take “hiatuses” from active duty. For instance, Bush got a six-week leave to work on Sen. Ed Gurney’s campaign in Florida. He then seemed to lose his skills as a pilot. He had difficulty landing his F-102 fighter plane. Consequently, he was pulled from flight duty, his last sortie being performed in April 1972.

Then, with many months still left on his National Guard contract, he asked permission to work on another senatorial campaign for Win Blount in Alabama. Bush requested, and was granted, a transfer to the 187th Tactical Reconnaissance unit in Montgomery at Dannelly Field. But there was no credible evidence in Alabama that Bush ever showed up.

When Blount lost in November of 1972, Bush returned to Texas, but not apparently to Ellington Air Base in Houston as he was supposed to. He went to Florida and Washington DC, and then returned to Alabama. He then tried to go back to Texas to report, but his superiors did not want him there. Further, there was never any paperwork returned to Ellington from Alabama about his alleged alternative service.

As many who have examined the record have concluded, it is hard not to say that young Bush went AWOL and did not fulfill the last two years of a six-year military commitment. That should have gotten him kicked out of the TANG and made him eligible for the draft. His negligence should have meant no honorable discharge, but he got one nonetheless.

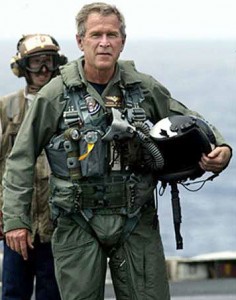

President George W. Bush in a flight suit after landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, to give his “Mission Accomplished” speech about the Iraq War.

Finessing a Vulnerability

Years later when Bush launched his political career, it appears that his handlers understood what a liability this whole episode was. Karl Rove and Karen Hughes tried to intimidate local Texas writers like James Moore from questioning Bush about it. But then, as Moore noted, there were reports from TANG manager Bill Burkett that some of Bush’s entourage went into National Guard Headquarters to purge Bush’s files. Whatever one thinks of Burkett’s credibility, there were indeed several documents missing from Bush’s file, which should have been there.

The first time I ever heard about the Bush/TANG story was during the presidential campaign of 2004, which tells us something about the national news media’s insistence on ignoring it when Bush first ran for president in 2000. Back then, much of the mainstream press was enamored of George W. Bush, who gave out nicknames to his favorite reporters. The campaign press was also generally disdainful of Vice President Al Gore, who was deemed a boring nerd.

During that campaign, Walter Robinson of the Boston Globe brought the story about Bush’s shirking his National Guard duty outside of Texas. Robinson interviewed several of Bush’s commanders who did not recall seeing him in 1972 or 1973, either in Texas or Alabama.

But that well-documented story fell on deaf ears as far as the national press was concerned. Big-time political reporters were much more interested in making fun of Gore for supposedly saying, “I invented the Internet” although Gore never actually said that. In 2000, within the Washington press corps, there was a palpable yearning for a return of the Bush Family “adults” and the dispatch of Bill Clinton’s tawdry entourage.

However, four years later, in Campaign 2004, retired Gen. Wesley Clark was running as a Democrat and documentarian Michael Moore had framed a possible Clark-Bush race as “The General vs. the Deserter.” So, during an early debate, ABC’s Peter Jennings asked Clark about the charge that Bush had gone AWOL in Alabama. Jennings was clearly trying to embarrass Clark or get him to repudiate Moore’s comment.

As Amy Goodman later recalled this exchange on her show Democracy Now, it appeared to be a warning shot by the mighty MSM: We are not going to tolerate this kind of criticism of a sitting president. Mainstream journalists also were a bit touchy because they had ignored this important angle in 2000.

Ignoring Bush’s Past

In retrospect, it seems amazing that the MSM almost completely missed this story in 2000, even though they had the Boston Globe story in hand. As Mapes writes in her book, what could be more relevant than a man running for president who had escaped the Vietnam draft by having strings pulled to get him into the TANG and who then decided he did not need to fulfill his rather easy weekend commitment and thus reneged on the terms of his agreement? Does such an episode not speak to Bush’s character, especially his honesty and sense of duty?

Further, since Bush’s experience in the TANG seemed to be a fig leaf to avoid service in Vietnam, what would that say about how Bush regarded the seriousness of sending other men into combat? Not only did Bush never experience the danger, he actively avoided it.

Was this issue not even more relevant considering what Bush later did in Afghanistan and Iraq in dispatching National Guard units to repeated combat tours? But the American public never got a chance to fully debate this issue because the MSM largely hid it from public view in 2000 and then insisted on keeping it buried in 2004.

Yet, Mapes plowed ahead with her work on the Bush-National Guard story. She obtained documents from Burkett purportedly written by Bush’s immediate supervisor, the deceased Jerry Killian, that seemed to corroborate much of what had been said earlier about Bush’s avoidance of service. The documents were copies, not originals, so the ink and paper could not be tested though she used other means to seek to authenticate them, including pressing Burkett on where he got them.

She also interviewed another TANG officer, Bobby Hodges, who had served above Killian. Hodges backed up the complaints about Bush that appeared in the documents, namely that Bush refused to report for a physical, that his superior wanted to call for a panel before grounding him, and that there was pressure from above to not discipline Bush. But Hodges refused to appear on camera and did not want to see the Killian documents. (Mapes, p. 173, e-book edition.)

To further verify the documents, Rather and Mapes secured the services of four document examiners. Of the four, two vouched for the documents as genuine and signed by Killian. Two had reservations. Mapes put together what she called an overall “meshing document,” a collection of unquestionably genuine documents, which matched the information in the documents secured by Burkett.

She wanted to make a comparison graphic to include on the show, but senior producer Josh Howard vetoed that idea in favor of more from House Speaker Barnes. (ibid, p. 187) Josh Howard also deleted the off-camera audio interview with Bobby Hodges. Howard and news vice president Betsy West cut another interview with a military expert, Colonel David Hackworth.

In her book, Mapes wrote that after these deletions, she probably should have either delayed the story, or perhaps asked for it to be killed. (ibid, p. 188) But she did not.

Tipping Off the White House

But there was one other development that should have given her pause. Producer Josh Howard allowed the White House to look at the documents and comment on the show in advance. The White House had no comment on the documents, and only a mildly dismissive reply to the thesis of the show, responding that Bush had been released from his National Guard service with an honorable discharge.

The lack of both rigor and vigor in this reply, considering it was just weeks before the election, should have signaled that something ominous was being prepared. Because the online response was so fast and ferocious, it appears that Bush’s defenders were tipped off in advance, a possibility that gained more credence after Bush published his account in his 2010 memoir, Decision Point.

According to Bush, he was shown one of the purported memos by White House aide Dan Bartlett after stepping off Marine One late one night in September 2004.

“Dan told me CBS newsman Dan Rather was going to run a bombshell report on 60 Minutes based on the document,” Bush wrote. “Bartlett asked if I remembered the memo. I told him I had no recollection of it and asked him to check it out.

“The next morning, Dan walked into the Oval Office looking relieved. He told me there were indications that the document had been forged. The typeface came from a modern computer font that didn’t exist in the early 1970s.”

Though Bush does not specify exactly when these conversations took place relative to the program, they suggest that the White House had a more central role in launching the right-wing blogger attacks over “forged” documents than was known at the time. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Bush Gloats Over Dan Rather’s Ouster.”]

The counterattack from rightwing web sites followed the attack line laid out by Bartlett. The bloggers ignored the interviews about Bush being AWOL and focused solely on whether the documents were genuine or if a Microsoft Word program on a computer created them.

Once the first critiques were published, the attacks on CBS spread throughout the conservative blogosphere, then conservative talk radio, and next onto Fox News, before becoming a hot topic in the MSM.

The IBM Selectric

The bloggers’ claim was that the IBM Selectric typewriter that Killian supposedly used to type his memos lacked technical features regarding types of fonts, superscripting and proportional spacing. But the Bush defenders were wrong. IBM’s Selectric typewriters did possess those features, meaning that the documents could have been typed back then. (ibid, pgs. 194-203)

The CBS experts had anticipated this line of attack. But what shocked Mapes was that even though the critics were proved wrong, that didn’t seem to matter as the MSM joined in the rush to judgment against CBS. Again, the attacks did not focus on the substance of the report the interviews indicating that the sitting president of the United States had essentially been a wartime deserter but on the trustworthiness of the Killian documents.

Rather than resist the media stampede, CBS president Andrew Heyward joined in trampling his reporting team. Heyward decided to rid CBS of the problem and satisfy CEO Leslie Moonves who never cared much for investigative reporting by appointing a blue-ribbon panel that certainly couldn’t be criticized for being biased against Bush, quite rather the opposite.

Also, if the panel did its job correctly and issued a scathing critique of Mapes and her team Heyward could begin to reorganize the news department and swing the nightly news more to “infotainment,” supposedly a more profitable approach to “news.”

Though Rather first resisted the growing attacks seeing them as par for the course when trying to hold a powerful person accountable he soon saw the writing on the wall. He apparently hoped to salvage the situation by issuing an apology.

In her book, Mapes describes Rather’s call in which he informs her about his apology and the appointment of the Thornburgh-Boccardi panel. Mapes wrote she started weeping at the news, because she understood that she was finished. (ibid, p. 230)

And she was. The Thornburgh-Boccardi panel was anything but independent. It was an appendage of Heyward and Moonves — and protective of President Bush. The panel had a job in front of it: to convict those involved with the segment, no matter what the real facts of the case were.

Boccardi, known inside the AP as a careerist bureaucrat who also was uncomfortable with investigative journalism, was mostly a front, the token “journalist.” The other key participants in the inquiry were attorneys with Thornburgh’s law firm. Therefore, Mapes would not be judged by a panel of working journalists using journalistic standards, but by prosecuting attorneys chosen and paid for by Heyward and Moonves.

People who cared about real journalism noted the bias and flaws in the inquiry. New York Times former corporate counsel James C. Goodale, who argued landmark freedom-of-the-press cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, dissected the Thornburgh-Boccardi report in an article in New York Review of Books.

His article was so trenchant that Thornburgh and Boccardi made the mistake of replying to it. Goodale’s rebuttal was even more compelling. Suffice it to say that the panel never tried to determine if the Killian documents were genuine, probably because, as time went on, more and more evidence emerged that a computer or word processor could not have created the documents.

Extreme blow-ups revealed evidence of wear on certain letters of the typeface, a sign that a real typewriter, not some word-processing software, was used. (ibid, p. 329)

Mapes’s Truth and Duty was a strong and energetic reply to the forces that combined to torpedo her career, retire Rather from CBS, and intimidate network investigative reporting. Mapes argues that the last point was particularly effective. I wouldn’t go as far as that, since I think those forces were at work long before 2004. If they weren’t, then the whole Bush/TANG issue would have come up for serious examination in 2000.

Making a Movie

Screenwriter James Vanderbilt evidently liked Mapes’s book. His credits had included movies, such as Zodiac and The Amazing Spider Man. However, when he finally got a chance to direct a film, he picked Truth and Duty.

Vanderbilt also resisted the Hollywood impulse to overly fictionalize real events. He kept the script very close to the book. As far as I could tell, whatever alterations were quite minor.

Vanderbilt begins the film, entitled simply “Truth,” on the eve of the November 2004 election, well after Mapes had been banished from CBS, and the Thornburgh-Boccardi panel had been appointed. We glimpse her in her attorney’s office. I thought this was a good way to start the movie, since it left the implication that Mapes’s fate would be impacted by the election and also that her story, if properly handled, could have decided that election.

We then flashback to the days after the Abu Ghraib story appeared, when Mapes and Rather still had their careers. We see Rather getting an award and Mapes playing with her young son in her Dallas home.

After the success of the Abu Ghraib story, she’s approached by new “60 Minutes II” producers who want her to pitch them a story idea. She chooses whether Bush ducked out on his National Guard duty. We then watch as the story is built, including Barnes being caught on private video camera boasting about getting Bush into the TANG.

But as the film dramatically shows, there were two reversals to the story that proved disastrous to Mapes. First, Burkett apparently misrepresented where and how he got the Killian documents. He told her that they were given to him by a National Guard higher-up named George Conn, who worked at a level above Killian.

However, after the segment aired — and the controversy was swirling — Burkett told CBS executives that his earlier account was not accurate, a deception that he said was meant to stop Mapes from pestering him about the documents’ provenance.

In his revised account, he said he got the documents from a woman named Lucy Ramirez, who then asked him to burn the copies that she gave him after he had copied them.

Flipping the Script

CBS New president Heyward understood how badly this revision reflected on the story. So, he asked Burkett to do an on-camera interview discussing it. Burkett agreed to do so. But, as the film shows, Heyward, through prime-time news vice president Betsy West, used this interview to demean Burkett and take some of the stigma away from CBS.

We watch as West pens note after note to give to Mapes, who gives them to Rather, each one trying to transfer blame onto Burkett until finally Mapes will not cooperate anymore and finally neither will Rather.

After the interview is over, Burkett’s wife comes out of their room at the hotel and is asked how her husband is doing. We know he is not doing well because we just saw him taking oxygen for a neurological ailment that afflicts him.

The wife laces into the New York media bigwigs for taking advantage of people like her and her husband, pretending to be interested in their lives when they aren’t, for using them and spitting them out at the end of the process. This sequence is probably the dramatic high point of the film, and much of its power comes from the vivid performances of Stacy Keach as Burkett and Noni Hazlehurst as his wife Nicki.

The other reversal for Mapes was when Hodges finally did look at the Killian documents and gave his opinion that they were not genuine. He added that when Mapes first described their contents to him, he thought they were handwritten.

The obvious question is whether these later interviews were influenced by the initial misguided furor over the capabilities of Selectric typewriters and whether the political significance of the controversy affected what was said later. As Mapes wrote in her book, once her blood was in the water, it quickly became a maelstrom.

The Mapes Portrayal

In the movie, Mapes is portrayed by Australian actress Cate Blanchett, a versatile, technically sure actress who is always in control of what she does. Her best moment is when Mapes learns that her father, a Republican, has joined in the public pummeling of her by calling into a talk radio station. Blanchett/Mapes, in a desperate, plaintive request, begs him to stop participating in his daughter’s public humiliation.

In the movie, there are two other scenes that I thought were visually arresting. When Mapes and her lawyer are ushered into the Thornburgh-Boccardi panel’s office, the camera swirls quickly to show us just how large the panel is — so large that it takes up two levels of tables and chairs in front of the witness.

The second directorial flourish is when Rather played by Robert Redford calls Mapes to tell her that he is being removed as anchor of the CBS Evening News, a position he held for nearly a quarter of a century. He is calling her from the exterior balcony of his penthouse in New York and he gets to the point of the call circuitously. He recalls that CBS first understood that it could really make big money off the news department with the success of “60 Minutes” on Sunday evenings.

Mapes senses that something is wrong or why would he call her at night to tell her that. Then, Rather lets her in on his removal.

As the conversation ends, the camera pulls back to a panoramic shot of the New York skyline, as Redford/Rather slowly lowers his head. It’s a subtle visual strophe which epitomizes a man who has lost everything that is dear to him in the world.

Redford’s Two Roles

There is also poignancy in the choice of Robert Redford to play Dan Rather. Earlier in his career, Redford played Bob Woodward in “All the President’s Men,” a rendition of The Washington Post’s famous Watergate investigation that led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. That story, set mostly in 1972, represented a different moment for the mainstream news media, a brief period when U.S. journalism sought to hold powerful officials accountable and did a much better job of informing the American people about government wrongdoing.

Late in “All the President’s Men,” Woodward and his colleague, Carl Bernstein, make a mistake by assuming that a witness had mentioned a name before the Watergate grand jury when he hadn’t because he wasn’t asked. Yet, instead of throwing the two reporters to the wolves for this error, Post executive editor Ben Bradlee decides to stand behind his reporters.

The movie, “Truth,” is a counterpoint to that earlier, more heroic moment of American journalism. Instead of backing brave reporters who got the story right even if the process was imperfect and messy, the new generation of news executives simply protects the corporation, shields the powerful, and sacrifices the honest journalists.

It’s also interesting that “Truth” appears almost exactly a year after Jeremy Renner’s “Kill the Messenger,” the account of how investigative journalist Gary Webb was destroyed by the mainstream press particularly The New York Times, The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times for disclosing the impact of cocaine trafficking by President Ronald Reagan’s beloved Nicaraguan Contras.

In this Contra-cocaine case, the major newspapers had largely ignored the scandal when it was first reported by AP reporters Robert Parry and Brian Barger in 1985 and even when it was the subject of a Senate investigative report by Sen. John Kerry in 1989.

When Webb revived the story in 1996 for the San Jose Mercury News focusing on how some Contra cocaine fed into the crack epidemic the MSM refused to reconsider its cowardly bad judgment of the 1980s and instead made Webb and some alleged shortcomings in his three-part series the issue.

The demonization of Webb continued even after the CIA’s Inspector General Frederick Hitz issued two reports confirming that the Contras had been deeply involved in the drug trade and that the CIA was aware of the problem but chose to protect its clients for geopolitical reasons rather than blow the whistle on their crimes. The blacklisting of Webb from his profession led to his suicide in 2004. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “How the Washington Press Turned Bad.”]

The two films have outwardly different subjects, but share a similar theme: how hard it is to tell the truth about difficult subjects in today’s corporate-controlled MSM news centers.

In both films, the central characters are remarkably successful news reporters who decide to pursue a subject that is anathema to the interests of the Establishment. They fail to understand the power of the forces arrayed against them, even when the counterattacks begin to pick up steam. They end up being victims of the corporate bureaucracies that they work for.

Although both stories are sad tales — no happy, triumphant endings — the fact that the films were made is encouraging because the public now can see how difficult it is to be an honest reporter in today’s environment. The powers available to stop serious investigative journalism in America are awesome and intimidating. Mary Mapes didn’t stand a chance.

James DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is Reclaiming Parkland.

I was a member of the 111th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 147th Fighter Group, Texas Air National Guard from 1967 to 1987. I was also selected to attend USAF Pilot Training and graduated 6 months ahead of Lt George W. Bush. As an operationally ready F-102 pilot, I volunteered for and participated in a temporary duty tour to the Vietnam theater assigned to the 509th Fighter Interceptor Squadron based at Clark AB, Phillipines. We flew combat and combat support missions in South Vietnam, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. Nine of the members of the 111th FIS participated in the program from 1968 to 1970. Lt Bush and another squadron pilot volunteered for the program but it was cancelled in 1970 when the 509th FIS transitioned from F-102 to F-4 aircraft.

The 111th Fighter Squadron has a proud history of service in World War II, the Korean War and provided 24 hour Air Defense Interceptor protection for our country for over five decades.

Mr. Roome:

You hardly seem a credible character witness for GWB considering a quick search of your name reveals “back stories” that call your objectivity into question.

“Certainly the most interesting of Bush’s witnesses were Major Dean Roome and Colonel Maury H. Udell. Together they did much to keep a lid on the Guard story straight through the 2004 election. Roome, who claimed to have been Bush’s formation flying partner and roommate during full-time fighter pilot training, provided journalists, including myself, with bland accounts of a fellow who never did anything interesting. “He was very friendly, and outgoing, affable, fun to be around, and, uh, just an overall super good guy,†Roome told me.”

http://whowhatwhy.org/2015/10/16/crucial-background-to-new-redford-movie-on-bush-and-rather-part-2/

SPRINGDALE, Ark. (AP) – The author of a book about George W. Bush has killed himself, police said.

James Howard Hatfield, 43, wrote Fortunate Son: George W. Bush and the making of an American President in 1999.

The unauthorized biography accused Bush of covering up a cocaine arrest. But during interviews about the book, Hatfield lied to reporters about his own criminal past.

A hotel housekeeper discovered the man’s body about noon Wednesday, Springdale police Detective Al Barrios said Thursday. Barrios said the man apparently overdosed on two kinds of prescription drugs.

Police don’t suspect foul play.

AP-WS-07-20-01 0709EDT

http://www.theforbiddenknowledge.com/hardtruth/author_of_bush_biography_dead.htm

Dan Rather, Hero or Zero?

By Greg Palast

There’s a new movie out about the supposed heroics of Dan Rather called ‘Truth.’ Unfortunately, the title is a lie, there’s little truth to be found in Rather’s story.

{For the real story of Bush and the Texas Air Guard, download Palast’s BBC film Bush Family Fortunes for free http://www.gregpalast.com/bffdownload/ }

Just three months before the 2004 election, Dan Rather had a story that might have changed the outcome of that razor-close race. Despite his self-glorifying fantasy in his film Truth, the fact is that Dan cut a back-room deal to shut his mouth, grab his ankles, and let his network retract a story he knew to be absolutely true.

It began on September 8, 2004, when Rather, on CBS, ran a story that Daddy Bush Senior had, in 1968, put in the fix to get his baby George out of the Vietnam War and into the Texas Air National Guard. Little George then rode out the war defending Houston from Viet Cong attack.

The story about the Family Bush is stone-cold solid. I know, because we ran it on BBC Television a year before CBS (see that broadcast at the link above). Neither I or BBC have ever retracted a word of it.

The full video is also available on Youtube. It has only gotten 54,000 views. That represents 0.017% of the American public. If Americans were paying attention, Jeb! Would not be running for President. He would probably be trying to convince a parole board that he should be released on good behavior. Other members of his family might have already been executed for treason. But hey, this is America…

It is very difficult to go after someone who has more power than you. That why the powerful have far less trouble than people with little power.

More importantly it is why a powerful country can kill millions of innocent people and suffer no repercussions.

I accessed a site called democracy.com before the 2000 election and learned about some of “Bush the Lesser’s” lies and criminal behavior on that site. I also learned that grand daddy Bush was making money from his investments supporting both the Allies and the Nazis, in WW Two, until he, and others, were stopped by the FDR administration. The family history has much which should make them ashamed, but that does not seem to be so!

I for one have never forgotten Dan Rather’s guilty look when, after being invited to a private showing of the Zapruder film, he reported to the American public, “The President’s head was thrown violently down and forward”. There are also credible criticisms of Rather’s coverage of Afghanistan. Individuals who had “boots on the ground”, first hand, eye-witness knowledge including Mary Williams Walsh that “stock footage” was substituted to bolster phony coverage. “Team B” under Richard Pipes along with Brzezinski came up with an artificially created terrorist threat to Moscow in the form of the Mujahideen to draw USSR into an invasion of Afghanistan. Then, the propaganda machine set loose a narrative claiming that Moscow’s motivation was not self defense, but ultimate control of the Arabian Peninsula’s oil resources. This resulted in the so-called “Carter Doctrine”. When the blowback from these shenanigans resulted in the tragedy of 9/11, Dan called upon Mika Brzezinski – the daughter of the architect of the disastrous foreign policy that contributed to it – for her “expert analysis”. When confronted with the seemingly too rapid Carl Rove response to Bush’s TANG record, Danny Boy didn’t display his signature closer – “Courage” – but instead rolled over and apologized on air. Hey, I’m not saying he was in on the scam. Maybe he really did “take the bait”. But hold a gun to my head and give me a life or death chance to guess the right answer, I’d say Rather was in on the plot to make this scandal go away.

For those who would like a realistic geopolitical evaluation of where we’re at right now, I’d suggest listening to this interview with Elizabeth Gould and Paul Fitzgerald on Spitfirelist.com. This is Dave Emory’s “For the Record” program #872. I realize Emory comes from left field on a lot of issues, but these guests are worth a listen.

http://emory.kfjc.org/archive/ftr/800_899/f-872.mp3

Thanks for the link F.G. Sanford, i’m listening now but I all ready like what I’m hearing.

I share your interest in Dan Rather because of his reporting on JFK, and find it odd, especially the head going forward reporting. Too, here is a partial list of reporters in and around Dealy Plaza on November 22, 1963:

Dan Rather

Bob Schieffer

Bill Moyers

Robert MacNeil

Hugh Aynesworth

Kind of what would become a who’s who of journalism,don’t you think?

I must thank James DiEugenio for the wonderful review; it is certainly a movie that stands with “Kill the Messenger,†I hope these insightful movies continue. And,as always, Robert Parry for this wonderful site.

Note that Bill Moyers’ stories are almost always non-controvrsial puff pieces which never really indict anyone. They fall into the “on the one hand this, and on the other hand that” category, but never lay any real blame. More than one researcher has claimed that he is CIA noting that Air Force One was held up in Dallas against Johnson’s wishes until Moyers could get onboard. I’m not expert enough on JFK esoterica to pass judgement, but everybody on that list, especially Schieffer, has been a shameless exponent of the official “big lie”.

Here is a link to the reference in the Emory audio mentioned in linked interview, about Nathan Freier, known unknowns;

http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB890.pdf

When the typewriter problem, was first presented, I didn’t buy into that one. I served in the Navy between 1968 & 1972. Besides, chipping paint and mopping the decks, I was around a lot of typewriters and teletypewriters. The military had quite a few pieces of equipment their civilian counterparts didn’t have. All communication typewriters, typed strictly all capital letters. This, I was told, was due to increasing the speed and efficiency, to handling all messages, in the fastest way possible. I am attaching a link, of the IBM typewriter history.

https://www-03.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/modelb/modelb_milestone.html

Anything maybe disputed of course, but browse the IBM webpage, and get a visual of what the IBM Selectric looked like. Remember, the other side of this story, could have meant, that Rather and Mapes were set up. So, the Bush defenders could have been given a great advantage, if the leaked papers had been written with an apparent flaw, such as the claim.

The comment takes the authenticity of the documents as more as less a given. But if they were forged, and quickly “refuted”, along with the true allegations therein, then….

Who produced the forgeries? I’ve seen little interest in the news media of what should be a logical area of inquiry.

Mary Mapes, Dan Rather, Gary Webb are no deviations, they belong to the growing number of journalists and whistleblowers to be silenced or persecuted.

Ashleigh Banfield was silenced by NBC, Raymond Bonner was denoted by the NYT, Daniel Simpson, Natasha Lenhard, Chris Hedges did quit. James Risen was harassed for his book State of War in connection with the Sterling case (Sterling was sentenced to 42 month). John Kiriakou was sentenced to 30 months. Sibel Edmonds is gagged (the “most classified woman in the USAâ€). The charges against Thomas Drake were dropped, but he was financially devastated, losing his NSA job and his pension.

Helen Thomas had to resign after criticizing Israel, Jesselyn Radack had to resign in connection with the Lindh case, Edward Snowden had to seek asylum in Russia, Julian Assange lives in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, Chelsea Manning is serving a 35-year sentence at the maximum-security US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth. Michael Hastings died in a suspicious automobile crash, Phillip Marshall, who like Webb and Hastings had received death threats, allegedly shot his two children and himself.

More US citizens have been indicted for violating the Espionage Act of 1917 under Obama than under all other previous presidents combined. The Obama administration has also turned down more Freedom of Information Act requests than any other prior presidency and the denial rate is constantly rising.

What does that mean for the future of journalism in the USA? Shall the honest truth tellers emigrate to safe havens? Are there any? (A few smaller western European and Latin American countries could qualify.)

Shall the journalists and whistleblowers go underground and use anonymous pasteboards on the web, direct contacts from computer to computer via heavily encrypted FTP protocols (Wired, KDX, Hotline, and others who cannot be named openly)? Smuggling data on tiny SD memory cards?

Even the NSA experts in Utah’s “Bumblehive†with their Cray XC30 supercomputers have difficulties to crack RSA keys with 1024 bit or longer and AES, RC4, and other cipher keys with 256 bit encryption. Open source protocols like ZRTP, CSpace (RedPhone, Signal), Zoho (TLS 1.2 protocols, 256 bit bit keys, SHA 256 certificates), OTR (ChatSecure), GNU, seem to be safe, while Skype and Tor may have NSA backdoors.

As it seems now, the Orwellian scene of US media will run its course until the imperium breaks apart under the weight of it’s internal contradictions. The truth tellers will have to migrate, go underground, or change their focus and instead of trying to reform the old system start to work in their close circle of friends and confidants, organize their local neighborhoods, and build up alternative networks plus support systems which are ready to replace the established state institutions when the breaking point finally is reached.

Please tell me and prove it that I’m wrong and too pessimistic!

ALONE IN THE WORLD

While the above is an important article in further explaining

why things are as they are, I always knew that was so.

Previously I had no more profound understanding.

For many, many years, I have not had a television

at all. As a youth, I confess that I did watch

a few favorite “shows” when young but not with

the vengeance people apparently do these days.

I have a CD player which I can barely hear

at all when the window to the Avenue is open,

filled as it is with police sirens, firetrucks, and

ambulances. I have an old radio which

loses some stations completely now and then.

Others consider me an odd fellow when I tell

them I don’t want a TV.

I did miss the World Series (baseball) but

in today’s world you must buy an “app”

and I surely would have fallen asleep as

many games were very long. I went to live

concerts instead at a nearby music

conservatory.

It follows that I have no “cell”, no “tweeter”,

texter or any other of the in-fashion inventions

of “hi-tech”. I appreciate emails . I have a “land-

line”.—..they used to be just called “telephones”.

(I remember my family’s first telephone number—

WOODLEY 6-0991—I rarely used it. I was too small.

These facts may make you uncertain about

the mental stability of this 21st century writer.

(I hear ads on the broadcasts of the baseball

games in the US most of which are for things

I have no experience—or interest—in. A

listener can go to the bathroom or do some

simple exercises while those ads are running.

A awake early in the morning to decipher what

is real in the lives of hundreds of thousands of

people across the seas.

One does learn after a time which writers

contribute incisive stories.

Many thanks for more information of the history

of what is termed journalism.

My role is to try as a simple single individual to

call attention of other views of the “facts” than

what is now termed “mainstream”.

“God Bless America”.

—Peter Loeb, Boston, MA, USA

Yes,the less contact with the Zionists and their myriad ways of brainwashing the world and Americans,reveals itself in your usual astute thoughts.My family won’t let me cut the cable,as I especially want now since TCM(my default)won’t let you copy their programming anymore,the sh*ts.And notice how baseball insults their fans by playoffs(WS still airs,hah) being only on pay TV.A giant sucking sound of do re mi.

The MSM met up with Bush before his election.i remember it distinctly.A deal was made,we(MSM)back you 100%,in your election (and his subsequent descent into the madness of neolibcon disaster)and you(shrub) back Israel 100%.End of freakin’ story,end of our freedom,and end of democracy.

Rather didn’t make a good case in his defense btw,he went belly up.

Dan didn’t have the right frequency,which is WZIO,or KZIO west of the Rockies.

Nice article Mr. DiEugenio, thank you.

Truth, Duty, Bravery and Honor — KIA; RIP; or The Forward March of Freedom (One Step Forward, Two steps Back)

This is an excellent essay by James DiEugenio. Along with filling in quite a bit of additional background detail for me on this deplorable episode in the Bush presidency, he has provided us — as if we really needed it — another sad indictment on the shabby state of the mainstream (corporate) media. I am very much looking forward to seeing the film equally as much as I did Kill the Messenger, one with which it will I’m sure share many themes.

With the issue of Dubya’s dubious TANG service record firmly in mind and the backstory behind it, it is instructive to note that in a speech delivered to Air Force Academy graduates in the summer of 2004 (incidentally 60 years apres D-Day), Number 43 succinctly and unambiguously summed up thusly his nouveau-imperial vision, the state of (his) empire and his brand of Pax Americana.

Here’s a sampler (link below):

‘Each of you receiving a commission today…will carry the hopes of free people everywhere. As your generation assumes its own duties during a global conflict….you will be called upon to take brave action and serve with honor. In some ways this struggle we’re in is unique…In other ways it resembles the great clashes of the last century between those who put their trust in tyrants, and those who put their trust in liberty…the goal of this generation is the same…..

…We’ll secure our nation and defend the peace through the forward march of freedom.’

What be wrong with this picture?

OK, well for one thing, when it came to taking “brave action” and serving “with honour” himself at the height of the ‘Nam War, the militarily eligible Dubya — not unlike his Veep Dick Cheney one suspects — was MIA, presumably preoccupied finding other ways and means to demonstrate his undoubtedly unique brand of bravery and honor in securing his nation and defending the peace thereof.

And if that isn’t “deplorable” enough for us, it would seem Dubya’s knowledge of his own country’s history was a tad deficient. In presenting this speech he seemed completely oblivious to or chose to overlook one simple, well-documented, and inescapable reality: That of the number of times both he and his predecessors — including it should be noted his old man Number 41 (Manuel Noriega anyone?) –- along with their political hacks and policy lackies have recidivistically placed their fervent trust in “tyrants”, folks whose own definition of “liberty” was the ‘liberty’ to plunder, loot and pillage their own countries and imprison, torture, rape, murder, and generally persecute their own citizens, mostly all with Uncle Sam’s blessing and even sometimes encouragement.

Which when we think about it, is the genesis of most of the problems of the empire, then and now!

And they still wonder why they are on the nose??!! Well, hello!!!

http://www.c-span.org/video/?182102-1/us-air-force-academy-commencement

http://poxamerikana.com/2015/10/16/of-smoke-n-mirrors-lost-in-the-wilderness-part-one/

Greg Maybury

Editor / Publisher

poxamerikana.com

“the MSM almost completely missed this story in 2000,” …. like many other ‘stories’ that MSM “miss” which criticise or expose wrong doing of today’s elite … the fact of the matter is that MSM has been in the hands of the right wing in the US & THE UK with specific instructions to turn out articles that support capitalism and Israel and should anyone dare to deviate their careers will be destroyed.

I read that a flight instructor recommended Bush be given further dual instruction

following an unsatisfactory check flight. The implication being that GWB had perhaps resumed alcohol/drug abuse. If so, would explain subsequent events.

Glad you brought that up.

Its a fascinating story that never got the attention it deserved.

I want to make it clear at the outset that I don’t actually know what happened with that grand mess. Like many other people, I furiously researched the matter at the time, and created for myself a conclusion which I’ve not yet seen any need to alter.

The fellow who the Supreme Court appointed as POTUS in 2000 really did go AWOL, but his “protectors” took good care of him, to the point of destroying the original documents. Before that was done, it’s my belief that the people who set up Dan Rather made almost-exact copies, but with enough easily visible problems to destroy the entire AWOL issue for that election.

Rather & Co. took the bait as expected, and according to the Wiki on this subject objections began coming in within an hour. That alone validates my belief a large number of people had been alerted to the story, and ready to pounce.

Karl Rove had already scored a major success with a similar technique in the 2000 election. As the story goes, a much bigger problem for that one was Bush’s cocaine conviction and the extraordinary way it was handled. And covered up.

James Howard Hatfield was the author of a fine biography of GWB. He appears to have been given an amazing amount of access to the inner circle, and by his own account, that included Karl Rove. Somebody (probably Rove) strongly hinted to Hatfield that Bush had been given a year of community service in 1972 for the cocaine conviction at a time when ordinary Texans didn’t have that privilege. Why would he do this? Because *somebody* knew Hatfield was a paroled felon, and release of that fact would instantly destroy the credibility of anything he had written!

And that’s exactly what happened. Seventy thousand books were recalled, twenty thousand more were left rotting in warehouses, and the story died. No more news coverage about that mysterious year when Bush did ‘volunteer’ work with “hardened black youth” in Houston. Did Rove mind when Hatfield later committed suicide? Did he mind when Rather lost his job? I doubt it.

In both cases a really substantial danger to the candidate was instantly turned into something the “mainstream media” would no longer touch with a 10-foot pole.

Excellent comment, Mr. Smith. And, an excellent piece by Mr. DiEugenio.

It is truly horrifying as well as enlightening to read this article. Can no one stand up and be heard with regard to the ugly/illegal behavior or the Bushes/Kennedys/Clintons? It appears not except when it suits the extreme right to pulverize those who don’t share their mantras.

GWB and Karl Rove aka Rover should be put on public display, hands and heads sticking thru the wooden medieval contraption, and publicly shamed. Nothing will happen to them unfortunately. They have literally gotten away with murder. The Bushes and their ilk are the wasp mafia.

The author makes the point that the media has changed and its glory highlight was Watergate.

I don’t think that is correct. In the Bush national guard affair, the media which admittedly has changed to be more infotainment, was inclined to protect one of theirs; to protect a guy who the media liked.

It was far different with Nixon, who was an object of scorn and derision from the time he stepped on the stage in the Hiss case and still, when the media wants to make an odious comparison, the name Nixon often comes up.

One was a self-made, socially clumsy outsider, the other a member of a family that had been members of the club for decades. One stepped on some toes of what are now the neocons early on, the other just a good ol’ boy who happens to be a war criminal but you wanted to share a drink with.

nixon was ‘self-made’?

he was hand-picked by prescott bush, w’s grandpappy

Prescott Bush is credited with creating the winning ticket of Eisenhower-Nixon in 1952.

George H. W. Bush had been chairman of the Eisenhower-Nixon campaign in Midland, Texas, in 1952 and 1956

nixon was a tool utilised by those more powerful than he

then, when he seemed to be veering off course

he was shown the door, ignomiously

Nixon,although greatly flawed,was an American,through and through.He didn’t cater to the Zionists like every one of his successors but Carter and Reagan,hence Carters bad rap from the monsters.Reagan helped their wealth immensely,and any real attacks on him by the Zios would have aroused his very large(confused) voting bloc.

Thank you! I and others were on top of this in the run up to the 2000 election, and desperately tried to get the MSM to pick up the story. We realized the fix was in when so many efforts were made to discredit the information. Glad there are others out there who knew the truth,