Given recent articles and books on the Bolshevik Revolution, which began Oct. 24, 1917 (Julian), it’s a struggle on the level of ideas that continues well into the 21st century, says John Wight.

Soviet 1920s propaganda poster — “The Unity of the Working People and the Communist Party Is Unbreakable!” (M. Lukyanov, IMS Vintage Photos, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

By John Wight

Medium

To its adherents, the Russian Revolution of October 1917 stands as the single most important emancipatory event in human history — of greater importance than the Reformation or the American and French revolutions preceding it.

To its adherents, the Russian Revolution of October 1917 stands as the single most important emancipatory event in human history — of greater importance than the Reformation or the American and French revolutions preceding it.

For them it went further than religious or political emancipation to engender social emancipation; and with it an end to the exploitation of man-by-man that describes the human condition fashioned under capitalism.

To its detractors October ushered in a dark night of communist tyranny under which, per Karl Marx, all that was holy was profaned and all that was solid melted into air. In this rendering October is considered, along with fascism, to have been part of a counter-Enlightenment impulse, one that arrived as the harbinger of a new dark age.

But here let us be in no doubt: the attempt to place communism and fascism in the same counter-Enlightenment box is ideologically and intellectually shallow, a product of the long struggle over the right to shape the future between capitalism and communism that raged over most of the 20th century.

It ended ultimately, so its detractors would have us believe, in the triumph of capitalism. However given the plethora of articles and books on the Russian Revolution which appeared in 2017, marking the event’s centenary, it is a struggle that continues on into the second decade of the 21stcentury — at least, certainly on the level of ideas

In his estimable 1995 work, Enlightenment’s Wake, conservative English philosopher John Gray dispels not only the attempt to establish a synthesis between communism and fascism, whose relationship could only ever be antagonistic, but also the attempt to create ideological and moral distance between communism and a European Enlightenment that gave the world the universality of liberal democracy, regardless of culture or tradition, as the non-negotiable arbiter of civilisation and human progress.

As Gray argues on page 48 of his book:

“Soviet communism did not emanate from a Russian monastery …. It was a quintessentially Western and European enlightenment ideology.”

(Enlightenment’s Wake, Routledge, 2007, page 48.)

In truth, the rendering of October from both the left and right of the political spectrum is lacking; each suffering from the inevitable distortion that comes with viewing the event through a skewed ideological prism.

Thus from the left — or should I say ultra left — an analysis underpinned by idealism rather than materialism predominates, while from the right we encounter a lapse into Manichaeism, rooted in a Kantian moral imperative which takes as its starting point the inference that the world exists on a blank sheet of paper; and that as such the only thing separating “good” from “bad” nations and their respective political systems is the “good” or “bad” character of the men and women responsible for forging them.

Lenin’s Evolving Perspective

Of the two competing narratives of October it has long been the view from the right that has predominated — i.e. the depiction of the event as a coup that succeeded in overthrowing and destroying the embryonic democracy that had begun to take shape in the wake the initial revolution of February 1917 in Petrograd, which had led to the Tsar’s abdication.

At the head of this Bolshevik dictatorship, we are led to believe, sat Vladimir Ulyich Lenin — a man so infamous his cognomen is among the most recognisable of any historical figure — who upon coming to power immediately unleashed unbridled terror against any and all who dared oppose him.

Here the sentiments of Orlando Figes are instructive:

“There was a strong puritanical streak in Lenin’s character which later manifested itself in the political culture of his dictatorship. He suppressed his emotions to strengthen his resolve and cultivate the ‘hardness’ he believed was required by the successful revolutionary: the capacity to spill blood for the revolution’s ends.”

(Figes’ Revolutionary Russia 1891–1991, Pelican, 2014, page. 23.)

Figes would have us believe that the development of Lenin’s leadership can be disconnected from the crucible in which it took place, forced to adapt to changing circumstances and conditions between the lesser-known and short-lived 1905 revolution, largely confined to Petrograd (now St Petersburg), and its universally recognised 1917 progeny. Such a one-dimensional and reductive categorisation can and must be dismissed as analytically and intellectually bereft.

As for Lenin’s supposed “puritanical streak,” didn’t Oliver Cromwell possess a puritanical streak? Was George Washington known for his sense of humour and levity? The stakes involved in the success or failure of a revolution — tantamount to life or death — are such that anything less than a puritanical streak when it comes to committing to its aims can only be fatal.

Bolshevik revolutionaries attacking tsarist police in the early days of the February Revolution of 1917. (From The Russian Bolshevik, by Edward Ross and Edward Alsworth; Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

But giving Orlando Figes and others of his ideological hue the benefit of the doubt for a moment, perhaps with the passage of time it is difficult to fully grasp the impact of mass poverty, immiseration, illiteracy and mass slaughter on Russian society and its people, a condition delivered them by a status quo of rigid autocratic rule in service to its own wealth and privileges.

Moreover the First World War — the midwife of the Russian Revolution — confirmed the willingness of Russia’s autocracy to shed an ocean of its people’s blood to maintain this wealth and uphold those privileges. When viewed in comparison, Lenin and the Bolsheviks’ “capacity to spill blood” paled.

In point of fact, Lenin’s preferred model of a revolutionary party at the turn of the 20th century was Germany’s SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands) with its mass membership, democratic structures, legal newspapers, clubs and associations.

But Tsarist suppression and the proscription of socialist organisations drove the Bolsheviks underground and its leadership into exile, where apart from brief periods they were forced to remain until 1917. (See Neil Faulkner’s A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, Pluto, 2017, pages 62–64).

Worker-Peasant Alliance

The most significant outcome of Lenin’s leadership post-1917 was the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. It represented a retreat from the revolution’s maximalist demands, borne of the failure of the civil war policy of war communism when it came to driving the country’s recovery in conditions of grievous economic and cultural backwardness.

Thus, at this juncture, NEP was essential not only to the revolution’s survival but to the country’s survival as complete economic and social breakdown beckoned. Under its provisions state control of economic activity was relaxed and market relations restored between the peasantry and urban centres with the aim of stimulating the economy. “There was no other credible alternative”, Tariq Ali points out, adding the crucial adjunct that in

“order to preside over this new transition, the revolutionary dictatorship had to be tough-minded and make sure that the revolution did not collapse.”

(Ali’s The Dilemmas of Lenin, Verso, 2017, page 311.)

NEP was introduced in obeisance to the weight of the peasantry in Russia’s economic and social life, constituting in 1917 approximately 80 percent of the population. With this in mind, the essential triumph of Lenin and the Bolsheviks was the triumph of the revolutionary alliance — smychka — forged between the urban proletariat and the peasantry, specifically the poor peasantry.

The Bolshevik slogan “Land, Peace and Bread” underpinned this alliance, outlining the revolution’s aims simply, succinctly and cogently.

Yet while the smychka may have been essential in the ability of the revolution to overthrow autocracy and its bourgeois cohort in October 1917, it was an impediment to the modernisation and industrialisation that was crucial to the revolution’s success and development thereafter. Here it must be stressed that revolutions do not take place in a vacuum and are not made under laboratory conditions.

When it comes to October, hostile troops of 14 countries were deployed to Russia at various points over the course of the civil war in support of the counter-revolutionary “White” armies arrayed against it.

In addition to the deployment of troops by the major and not-so-major capitalist powers, a determined attempt at economic asphyxiation with the introduction of a blockade was also undertaken — factors that cannot be gainsaid when analysing the course of the revolution’s development and disfigurement.

The risks inherent in NEP were clear. By retreating in the face of the backwardness of the countryside, the Bolsheviks were merely deferring a reckoning with the peasantry until a later and more propitious time. There was the added risk of capitalist norms becoming entrenched, along with their political and social consequences.

As Jonathan D Smele outlines:

“Just as the Bolsheviks had been obliged to accept, at Brest-Litovsk in 1918, a humiliating peace treaty with Austro-German imperialists as the price for survival, so too, in 1921, in surrendering ‘War Communism’ (sic) in exchange for the NEP, they put their signatures to a ‘peasant Brest.’”

(Smele’s The Russian Civil Wars 1916–1926, Hurst, 2015, page 243.)

Objective Conditions

That Russia in 1917 was the least favourable country of any in Europe for socialist and communist transformation is indisputable. The starting point of communism, Marx avers in his works, is the point at which society’s productive forces have developed and matured to the point where the existing form of property relations acts as a brake on their continuing development.

By then the social and cultural development of the proletariat has incubated a growing awareness of their position within the existing system of production; thereby effecting its metamorphosis from a class “in itself” to a class “for itself” and, with it, its role as the agent of social revolution and transformation.

Marx:

“No social order ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed; and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society itself.”

(Preface from A Contribution To The Critique of Political Economy: Marx, Later Political Writings, Cambridge 2012, page 160.)

The error in Marx’s analysis was that rather than emerge in the advanced capitalist economies of Western Europe, communism was destined to emerge on the periphery of those capitalist centres — Russia, China, Cuba et al. — in conditions not of development or abundance but under-development and scarcity.

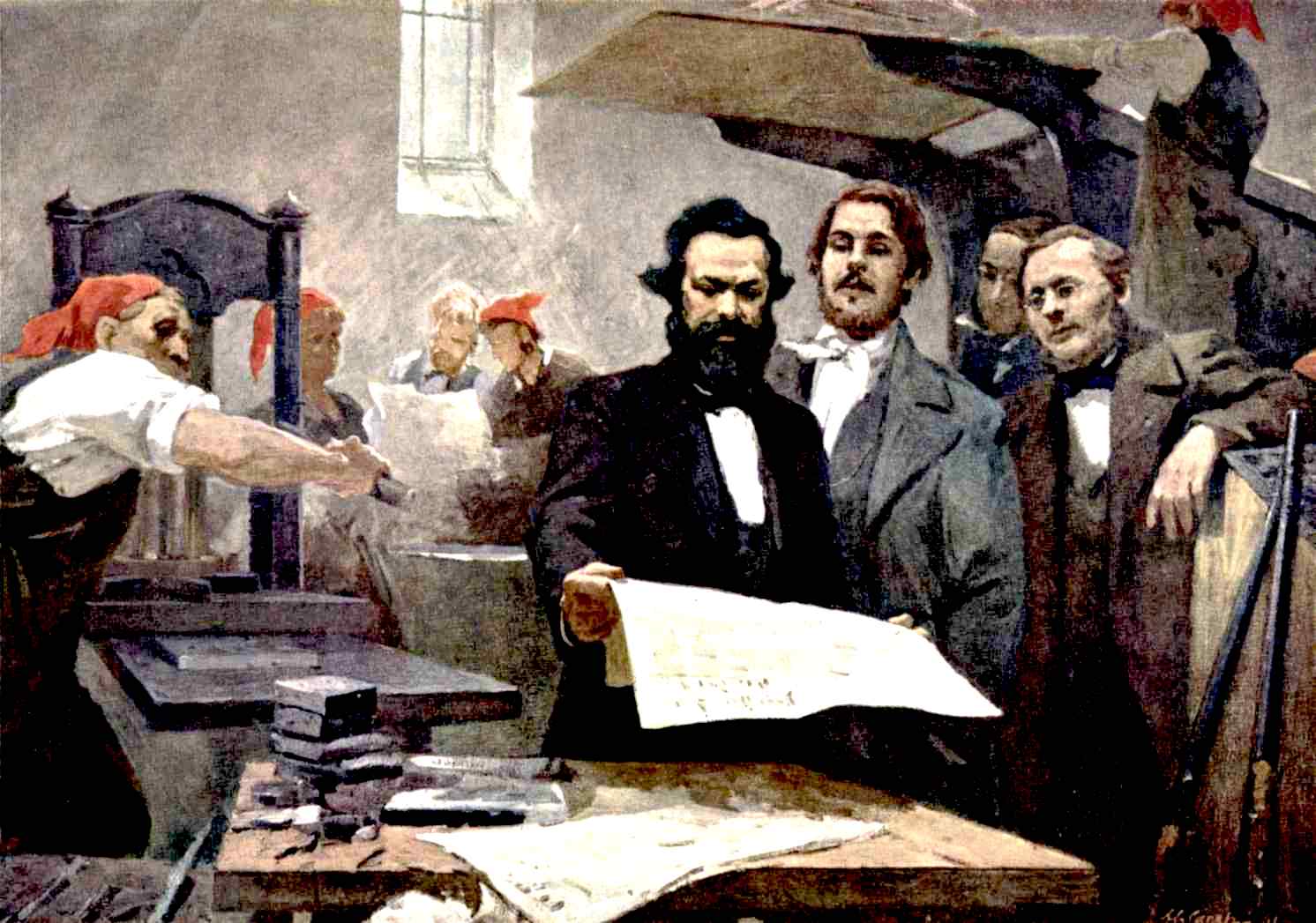

1895 oil painting by E. Capiro of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the printing house of their German daily Neue Rheinische Zeitung. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The event responsible for creating the objective conditions out of which October emerged was, as mentioned, the First World War. It resulted not in the expansion of the Russian Empire, as the country’s tsarist autocracy intended, but in its own destruction.

Recounting the start of the 1914–18 war, which found him in exile in Vienna, Trotsky observed how:

“mobilisation and declaration of war have veritably swept off the face of the earth all the national and social conditions in the country. But this is only a political delay, a sort of political moratorium. The notes have been extended to a new date, but they will still have to be paid.”

(Trotsky’s My Life, An Attempt at an Autobiography, Charles Scribner, 1930, page 234.)

From the vantage of exile in Switzerland, Lenin discerned with uncommon clarity that the war presented revolutionaries across Europe with a clear choice. They could either succumb to national chauvinism, fall into line behind their respective ruling classes and support their respective countries’ war efforts, or they could use the opportunity to agitate among the workers of said countries for the war to be turned into a civil war in the cause of worldwide revolution.

It was a choice separating the revolutionary wheat from the chaff, leading to the collapse of the Second International as with few exceptions former giants of the international Marxist and revolutionary socialist movement succumbed to patriotism and war fever.

Lenin:

“The war came, the crisis was there. Instead of revolutionary tactics, most of the Social-Democratic [Marxist] parties launched reactionary tactics, went over to the side of their respective governments and bourgeoisie. This betrayal of socialism signifies the collapse of the Second (1889–1914) International, and we must realise what caused this collapse, what brought social-chauvinism into being and gave it strength.” (Lenin’s Revolution, Democracy, Socialism, Pluto, 2008, page 229.)

Lenin speaking in Moscow’s Red Square on May Day 1919. (Chairman1922, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Lenin’s analysis proved accurate. The ensuing chaos, carnage and destruction wrought by four years of unparalleled conflict brought the so-called civilised world to the brink of collapse. The European continent’s ruling classes had unleashed an orgy of bloodshed in the cause not of democracy or liberty, as the Entente powers fatuously claimed, but over the division of colonies in Africa and elsewhere in the under and de-developed world

The result in Russia was the collapse of Tsarist autocracy under the weight of social contradictions which the war intensified and made insurmountable. The ostentation and decadence of the Tsar’s court had been erected on the bones of the peasantry and an inchoate urban proletariat, whose relationship to the means of production had begun to mould it into a political as well as social entity.

Stalin’s Rise to Power

NEP, as mentioned, marked the ebb tide of the post-October revolutionary emancipatory wave, and was introduced in de facto recognition of the Russian peasantry’s economic and social weight.

It was October’s defining contradiction, one that produced splits and schisms within the Bolshevik leadership under pressure of the dark clouds of reaction that were, by the time of Lenin’s death in 1924, already looming in the capitalist West.

From the left, or at least a significant section of the international left, the analysis of October and its aftermath is coterminous with the deification of its two primary actors, Lenin and Trotsky, and the demonisation of Stalin; depicted as a peripheral player who hijacked the revolution upon Lenin’s death, whereupon he embarked on a counter-revolutionary process to destroy its gains and aims.

For example, Neal Faulkner would have us believe that

“the party-state bureaucracy that had emerged in Russia under Stalin’s leadership was, by 1928, strong enough to complete what was, in effect, a counter-revolution. It had been accumulating power for a decade, and when it moved decisively at the end of the 1920s, it was able to destroy all remaining vestiges of working-class democracy.”

(Faulkner’s A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, Pluto, 2017, page 245).

In actual fact, the “working-class democracy” Neal Faulkner describes was not ended by Joseph Stalin but by Lenin — with the support of his comrades, including Leon Trotsky — at the 21st Congress of the Communist Party in 1921 (the Bolshevik Party changed its name to the All-Russian Communist Party in 1918 upon its formal assumption of power) with the ban on factions. This was effected under the auspices of Lenin’s “Decree on Party Unity” resolution.

In the tempest of the civil war that had ensued after the revolution, and the concomitant threat to its survival, Lenin’s decree determined that the working-class democracy envisaged prior to the revolution was relegated to an objective that would be achieved in a future yet to be determined.

Writing in the second volume of his magisterial three-part biography of Trotsky, The Prophet Unarmed, Isaac Deutscher describes how the Bolsheviks were aware that

“only at the gravest peril to themselves and the revolution could they allow their adversaries to express themselves freely and to appeal to the Soviet electorate. An organized opposition could turn the chaos and discontent to its advantage all the more easily because the Bolsheviks were unable to mobilize the energies of the working class. They refused to expose themselves and the revolution to this peril.”

(The Prophet Unarmed, Oxford 1959, page 15.)

The harsh reality is that the cultural level of the country’s nascent and small proletariat, whose most politically advanced cadre would perish in the civil war, was too low for it to take the kind commanding role in the organisation and governance of the country Lenin had hoped and anticipated:

“Our state apparatus is so deplorable, not to say wretched, that we must first think very carefully how to combat its defects, bearing in mind that these defects are rooted in the past, which, although it has been overthrown, has not yet been overcome, has not yet reached the stage of a culture, that has receded into the distant past.”

(Revolution, Democracy, Socialism, Pluto, 2008, page 338.)

Stalin’s victory in the struggle for power that ensued within the leadership in the wake of Lenin’s death was, according to conventional wisdom, down to his Machiavellian subversion and usurpation not only of the party’s collective organs of government, but the very ideals and objectives of the revolution itself.

This though is a reductive interpretation of the seismic events, both within and out with Russia, that were in train at this point.

The key ideological questions splitting the leadership of the party post-Lenin were over the primacy of the countryside versus the primacy of the city when it came to the country’s economic and industrial development, along with the merits of Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution” as opposed to Stalin’s formulation of “socialism in one country.”

As mentioned, October had been based on the centrality of the smychka — the worker-peasant alliance. However towards the end of the civil war it was an alliance that came under increasing strain as the socioeconomic contradictions between the countryside and the city came into ever-sharper relief. And it is here where the accusation that Stalin embarked on a counterrevolutionary process upon taking the helm after Lenin’s death is untenable.

When it came to Trotsky, even after the failure of the second German revolution in 1923, his pre-1917 conception of October as the prologue to world revolution— without which it would be condemned to remain a prisoner of the primitive human and cultural material of pre-revolutionary Russia — remained unshakeable.

At the same time his view of the peasantry, which had led to accusations of him underestimating its potential as a progressive factor in the revolution’s development, was more or less unchanged from the view he held in 1905, when he was writing that the

“knot of Russian social and political barbarism is tied in the village; but this does not mean that the village has brought forth a class capable of cutting it.”

(The Basic Writings of Trotsky, Secker & Warburg, 1964, page 53.)

Leon Trotsky

West German students holding a placard of Leon Trotsky in 1968. (Stiftung Haus der Geschichte, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Despite Trotsky’s determination to hold onto the belief in the catalysing properties of October with regard to worldwide revolution — which he shared with Lenin — by the time of the latter’s death in 1924, it was clear that the prospect of any such revolutionary outbreak in the advanced European economies had ended, and that socialism in Russia would have to be built, per Bukharin, “on that material which exists.”

Trotsky and Lenin’s mistake in placing their hopes in the European proletariat, and the accuracy of Stalin’s scepticism in this regard, cannot be gainsaid.

Isaac Deutscher:

“After four years of Lenin’s and Trotsky’s leadership, the Politbureau could not view the prospects of world revolution without scepticism … The process by which European feudalism was abolished lasted centuries. How long would capitalism be able to resist … Thus extreme scepticism about world revolution and confidence in the reality of a long truce between Russia and the capitalist world were the twin premises of his [Stalin’s] ‘socialism in one country’.” (See Deutscher’s, Stalin: A Political Biography, Oxford, 1967, page 391.)

Bukharin’s Socialism With a Human Face

Opposing Trotsky on the question of the peasantry in the mid-1920s, Nikolai Bukharin was the most passionate champion of the continuation of the worker-peasant alliance as the key to the revolution’s future, which he advocated should ensue along an evolutionary rather than revolutionary path from here on in — i.e. that the era of social convulsion should give way to an era of social peace and equilibrium

Arguments on the left of the party in favour of hyper-industrialisation on the back of the peasantry, utilising the coercive methods that had been employed under war communism to extract the grain required to feed the towns and cities, while exporting the surplus in order to obtain the heavy machinery and equipment necessary for industrial development, were for Bukharin and his supporters anathema.

Instead, NEP should remain the cornerstone of the economy with its emphasis on incentivising the peasantry to increase the yield of agricultural goods and commodities it produced through a reduction in industrial prices, which were controlled by the government. Thus industrialisation in the city would take place on the back of consumer demand in the countryside.

“According to Bukharin,” his biographer Stephen F. Cohen writes, “the NEP market economy had established ‘the correct combination of the private interests of the small producer [in the countryside] and socialist construction.’”

This being said, Bukharin’s vision of maintaining NEP as the fulcrum of development was for him not only an economic question but also an ethical one. “Bukharin was groping toward an ethic of socialist industrialisation,” Cohen asserts, “an imperative standard delineating the permissible and the impermissible.”

(Cohen’s Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution, Wildwood, 1974, page 171.)

Bukharin delivers the welcome speech at the meeting of Young Communist International, 1925. (Ogoniok issue 17, April 19, 1925; Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Bukharin’s position in the mid 1920s, supported by Stalin against the Left Opposition triumvirate of Trotksy, Kamenev, and Zinoviev, turned on the philosophical question of is/ought. For Bukharin, whom Lenin had regarded as the favourite of the party, lionised as its preeminent theorist during the height of his prestige, socialism was as much an essential mechanism for human development as it was for industrial and economic development.

“The principle of socialist humanism,” he opined, involved “a concern for all–round development, for a many-sided life.” Further, he asserted that “the machine is only a means to promote the flowering of a rich, variegated, bright, and joyful life,” where “people’s needs, the broadening and enrichment of their life, is the goal of the socialist economy.” (Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution, page 363.)

In the context of the epic and brutal events of the Soviet Union in the 1930s, Bukharin’s sentiments stood as a lone beacon of humanity amid the looming clouds of terror that were about to engulf the country.

He himself was destined to be the terror unleashed by Stalin’s most significant victim, sent to his death on fabricated charges of treason and counterrevolutionary intrigue by his one time comrade and fellow Old Bolshevik, Stalin, in 1938.

Stalin’s Terror Unleashed

The terror unleashed by Stalin against his former comrades and tens of thousands of functionaries and officials occupying the lower echelons of the party and state institutions between 1936 and 1938 is commonly accepted as as an exercise in evil for evil’s sake, one in which the Soviet leader is reduced to a pantomime villain and latter day Genghis Khan.

Though the savagery and brutality of the period is undeniable, arriving at a serious understanding of its place in the history of October does, nonetheless, require that we take into account its specific political and historical context.

By 1931 any pretence of continuing the worker-peasant alliance that was the fulcrum of the revolution in 1917, and the basis of Bukharin’s vision of an evolutionary approach to its continuing development, was over.

Though Stalin, during the period of the triumvirate he forged with Kamenev and Zinoviev between 1923 and 1926 in opposition to Trotsky, had paid lip service to this rightist approach to economic and industrial development, the food crisis of 1928–29, leading to the serious risk of famine, saw him undergo a volte-face.

Add to this events unfolding in Western Europe, what with the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany, and the gathering storm both within and without was real. (See Isaac Deutscher’s Stalin: A Political Biography, Oxford, 1967, page 322.)

Isaac Deutscher writes,

“The first of the great [show trials], that of Zinoviev and Kamenev, took place a few months after Hitler’s army had marched into the Rhineland; that last, that of Bukharin and Rykov, ended to the accompaniment of the trumpets that announced the Nazi occupation of Austria.”

Even then, Deutscher goes on, Stalin was under

“no illusions that war could be altogether avoided; and he pondered the alternative courses — agreement with Hitler or war against him — that were open to him. In 1936 the chances of agreement looked very slender indeed. Western appeasement filled Stalin with forebodings. He suspected that the west was not only acquiescing in the revival of German militarism but instigating it against Russia.” (Page 376)

As to the relevance of these events to the show trials and mass purge of Old Bolsheviks that was underway, Deutscher posits the thesis that

“in the supreme crisis of war, the leaders of the opposition, if they had been alive, might indeed have been driven to action by a conviction, right or wrong, that Stalin’s conduct of the war was incompetent and ruinous…Let us imagine for a moment that the leaders of the opposition lived to witness the terrible defeats of the Red Army in 1941 and 1942, to see Hitler at the gates of Moscow…It is possible they would have then attempted to overthrow Stalin. Stalin was determined not to allow things to come to this.” (Page 377.)

Brutal logic, perhaps, but logic nonetheless.

Stalin’s Five-Year Plans

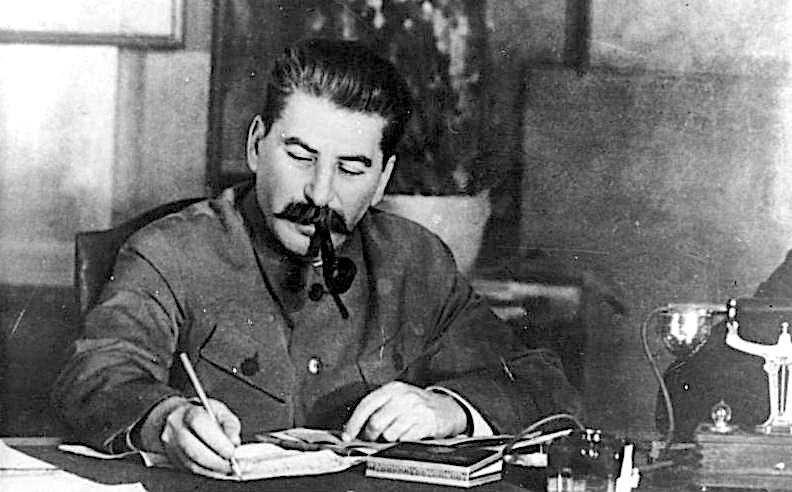

Stalin in 1949. (Bundesarchiv, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

In response to the food crisis of 1928–29, Stalin — by now approaching the summit of total power — introduced the first of the five-year plans devised with the aim of achieving rapid industrialization. “We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries,” he declared in 1931. “We must make good this lag in ten years. Either we do it or they crush us.”

(See Isaac Deutscher’s Stalin: A Political Biography, Oxford, 1967, page 328.)

The catastrophic human cost of hyper-industrialisation is not in dispute, especially on the part of the countryside, where forced collectivisation of the peasantry into state run farms caused havoc. Crucially, by now there was no attempt to make any political distinction between the poor peasantry and Kulaks (wealthier peasants who owned farms and hired labourers). All were lumped together as enemies of the people with earth-shattering consequences.

The hard but crucial question when it comes to collectivisation is this though: Could it have been avoided given events underway in the rest of Europe vis-a-vis the rise of fascism and resulting threat of war?

The question answers itself if we accept that without Stalin’s programme of hyper-industrialisation the ability of the Soviet Union to prevail in the face of the Nazi onslaught that was unleashed against the country in 1941 would have been impossible to imagine.

Supporting this assertion is the fact that between 1928 and 1937 coal production in the Soviet Union rose from 36 million to 130 million tonnes: iron from 3 million to 15 million tonnes: oil from 2 million to 29 million tonnes: and electricity from 5000 kilowatts to 29,000 kilowatts. Meanwhile, over the same period, major infrastructure projects were completed, while advances in education, particularly technical subjects, were also phenomenal.

Again, the price paid by millions of men, women, and children for those achievements was inordinate. It is why those guilty of romanticising October would do well to linger on the fact, previously touched upon, that revolutions are not made under laboratory conditions; their trajectories and outcomes are less the product of moral design and more the result of a merciless struggle against specific and concrete material, cultural and external factors.

“Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby,” Marx cautioned over half a century before 1917, with a cogency and prescience confirmed by the trajectory of October in its aftermath. (Marx: Later — Critique of the Gotha Programme, Cambridge, 2012, page 214.)

As for those who cite the human cost of October and its aftermath as evidence of its unadulterated evil, no serious student of the history of Western colonialism and imperialism could possibly argue its equivalence when weighed on the scales of human suffering.

Here Alan Badiou reminds us that

“the huge colonial genocides and massacres, the millions of deaths in the civil and world wars through which our West forged its might, should be enough to discredit, even in the eyes of ‘philosophers’ who extol their morality, the parliamentary regimes of Europe and America.”

(See Badiou’s The Communist Hypothesis, Verso, 2008, page 3.)

The process of industrialisation, regardless of where and whenever embarked upon, has always exacted a heavy price in human suffering. Whether we are talking about the century-long Industrial Revolution which transformed the British economy and society between the mid 18th and 19th centuries, (see Friedrich Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England, Penguin, 1987) or whether the industrialisation of the United States that occurred afterwards in a process that also included the 1861–65 Civil War, (see Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, Harper Collins, 1999, pages 171–295) it is a historical fact that remains impervious to contradiction.

Thus we can say that those generations forced to pay the price of industrialisation throughout the developed world are owed a debt of gratitude by the succeeding generations that have reaped its benefits and rewards.

October’s Place in History

No revolution or revolutionary process ever achieves the ideals and vision embraced by its adherents at the outset. Revolutions advance and retreat under the weight of internal and external realities and contradictions, until arriving at the state of equilibrium that conforms to the limitations imposed by the particular cultural and economic constraints of the space and time in which they are made.

Though Martin Luther advocated the crushing of the Peasants Revolt led by Thomas Munzer, can anyone gainsay Luther’s place as one of history’s great emancipators?

Likewise, while the French Revolution ended not with the liberty, equality, fraternity inscribed on its banners but instead the Emperor Napoleon, who can argue that at Waterloo the cause of human progress was represented by the Corsican general’s Grande Armee against the dead weight of autocracy and aristocracy represented by Wellington?

In similar vein, Stalin’s socialism in one country and resulting five-year plans allowed the Soviet Union to overcome the beast of fascism in the 1940s.

It is why, in the last analysis, the fundamental and lasting metric of the October Revolution of 1917 is the Battle of Stalingrad of 1942–43. And for this, whether it cares to acknowledge it or not, humanity will forever be in its debt.

John Wight, author of Gaza Weeps, 2021, writes on politics, culture, sport and whatever else. Please consider taking out a subscription at his Medium site.

This article is from the author’s Medium site.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Wight writes of “a dark night of communist tyranny under which, per Karl Marx, all that was holy was profaned and all that was solid melted into air.”

That’s from the Communist Manifesto, and describes social relations under capitalism!

“THE BOURGEOISIE [my emphasis] cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

To what extent did the support of independence movements in Africa and Asia by the USSR help people to overthrow colonialism? Despite the problems and mistakes and questionable outcomes perhaps it was a preferable scenario compared to a continuation of colonial rule.

Trotsky worked with Nazis and ran a conspiracy to topple the Soviet system under Stalin.

Professor Grover Furr has done some of the most groundbreaking and enthralling work of this century uncovering countless documents proving Stalin wasn’t a dictator and that the defendants in the “show trials” were actually guilty of conspiracy.

Lenin is reported to have said to Trotsky, shortly before his death, “Oh my god, what have we done?” C.L.R James reports hearing this from Trotsky’s secretary.

Your use of the word ‘proving’ suggests that Furr’s claims are beyond dispute, when some of the charges in those trials were so obviously ludicrous they could only have been made in a dictatorship, let alone resulted in a guilty verdict.

I can’t believe the only comment is not some bs reference to that charlatan Solzhenitsyn or some such. Brace yourself however, it is coming.