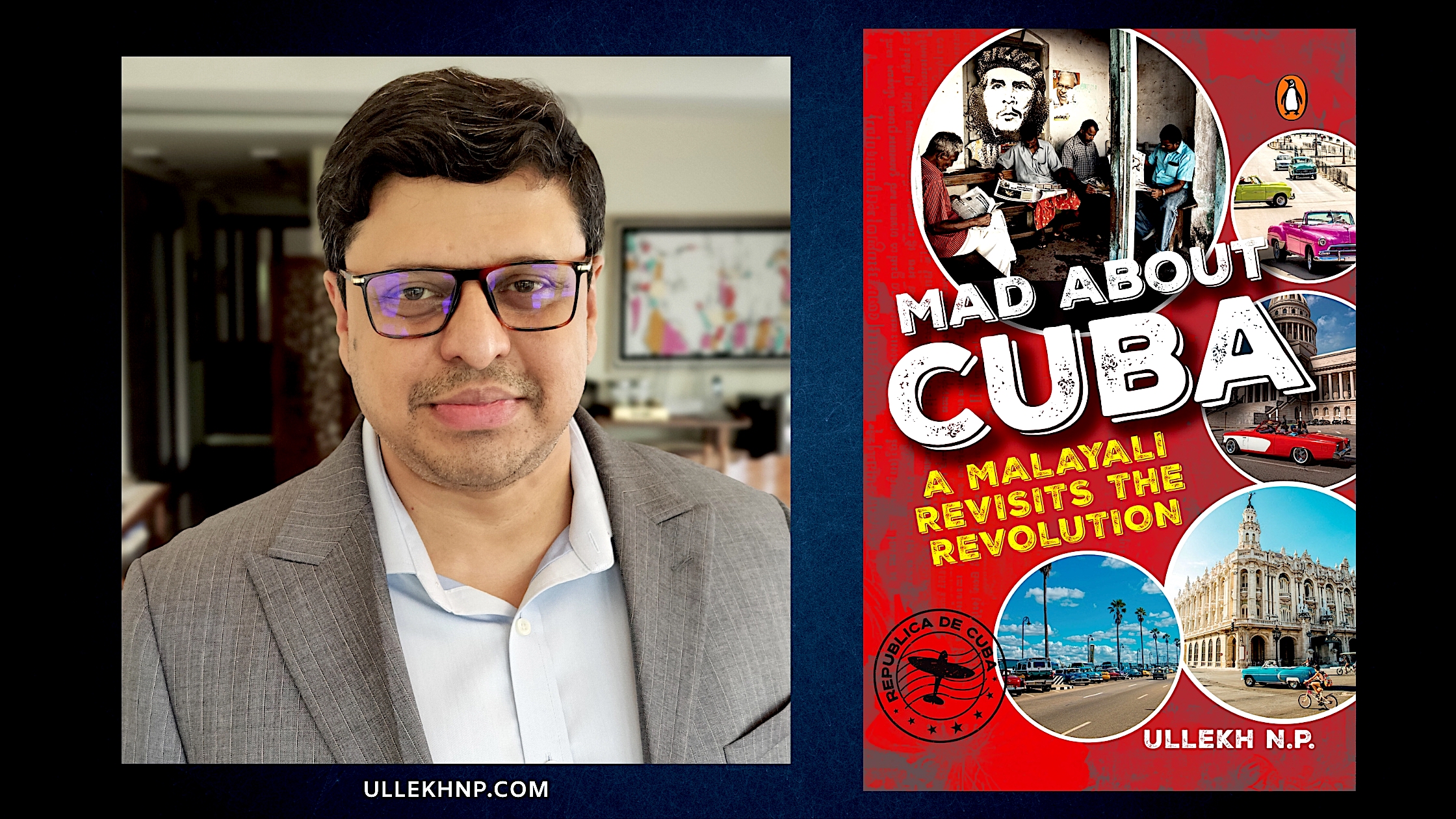

Ullekh NP begins with Che the revolutionary, whose many sides are yet undiscovered, in these excerpts from his new book, Mad About Cuba: A Malayali Revisits the Revolution.

The following is an excerpt from Mad About Cuba: A Malayali Revisits the Revolution by Ullekh NP (Published by Penguin India).

The following is an excerpt from Mad About Cuba: A Malayali Revisits the Revolution by Ullekh NP (Published by Penguin India).

The book was published 10 years after Barack Obama and Raul Castro announced the resumption of diplomatic ties between the U.S. and Cuba in 2014, six years after Donald Trump reversed those policies, ending Obama’s ‘thaw’, and three years after Trump placed Cuba on the list of terrorism-sponsoring countries.

Joe Biden who came to power in 2021 replacing Trump will now leave office on Jan. 20 without reversing any of Trump’s decisions aimed at strangling Cuba economically. He will be the 12th American president to ensure the long-term goal of ‘regime change’ in the Caribbean nation.

The book is released as Trump’s re-election raises huge concern for Cuba, which has been grappling with the 64-year-old U.S.-imposed blockade that has lately pushed Cuba into a situation worse than what it had faced during the Special Period in the 1990s. Annually, the U.N. General Assembly has voted overwhelmingly in favour of a resolution asking the U.S. to lift its embargo on Cuba since 1992, but the Americans, who find themselves isolated over the issue, have refused to relent.

From the Amazon.com description: “Mad About Cuba documents his visit and observations. Through conversations with senior bureaucrats, scientists at Cuba’s fabled pharma research institutes, youth beginning their careers, students and many others, he paints an intimate and objective picture of the nation that has managed to withstand American sanctions for over six decades.”

By Ullekh NP

We in Kerala (in southern India) assume we know so much about Che Guevara whose life and times have been widely documented. But we realize, thanks to stellar works by a precocious new generation of scholars, that we know very little about him.

We in Kerala (in southern India) assume we know so much about Che Guevara whose life and times have been widely documented. But we realize, thanks to stellar works by a precocious new generation of scholars, that we know very little about him.

Though Guevara tried to persuade socialist nations to replace capitalist mechanisms by offering them alternative policies, his warnings were not heeded and eventually, capitalism returned to all those countries. ‘In Cuba, his analysis was revisited in the mid-1980s in the period known as Rectification, which pulled the island away from the Soviet model before it collapsed, arguably contributing to the survival of Cuban socialism,’ says U.K.-based academic Helen Yaffe.

Guevara also believed, avers Dr. Michelle Paranzino, author of The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Cold War: A Short History with Documents, that the most salient divisions were not between the capitalist and communist blocs, but between the Global North — the industrialized economic powers, including the Soviet Union and other highly developed economies of the Eastern bloc — and the Global South.

‘The latter term was understood as including not only the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America — in other words, the decolonising world — but also the subject peoples within the industrialized countries, particularly African Americans in the United States,’ she writes.

And yet, I return to Che the revolutionary, whose many sides are yet undiscovered. None less than Garcia Marquez wrote about Che Guevara’s decision to leave Cuba on 25 April 1965 to fight the guerilla war in the Congo, which points as much to the intensity of the Cuban presence there as to Guevara’s own internationalism. After submitting his farewell to Fidel Castro, Guevara relinquished his rank of commander and other functions in the government.

Marquez writes in an essay titled ‘Operation Carlota’:

“He travelled alone on commercial airlines, under cover of an assumed name and an appearance only slightly altered by two expert touches. His briefcase contained works of literature and numerous inhalers to relieve his insatiable asthma; he would while away the dull hours in hotel rooms playing endless games of chess with himself … Che Guevara remained in the Congo from April to December 1965, not only training guerrillas but leading them into battle and fighting by their side ….

After Moises Tshombe was overthrown, the Congolese asked the Cubans to withdraw in order to facilitate the signing of the armistice. Che left as he had come: without fanfare.”

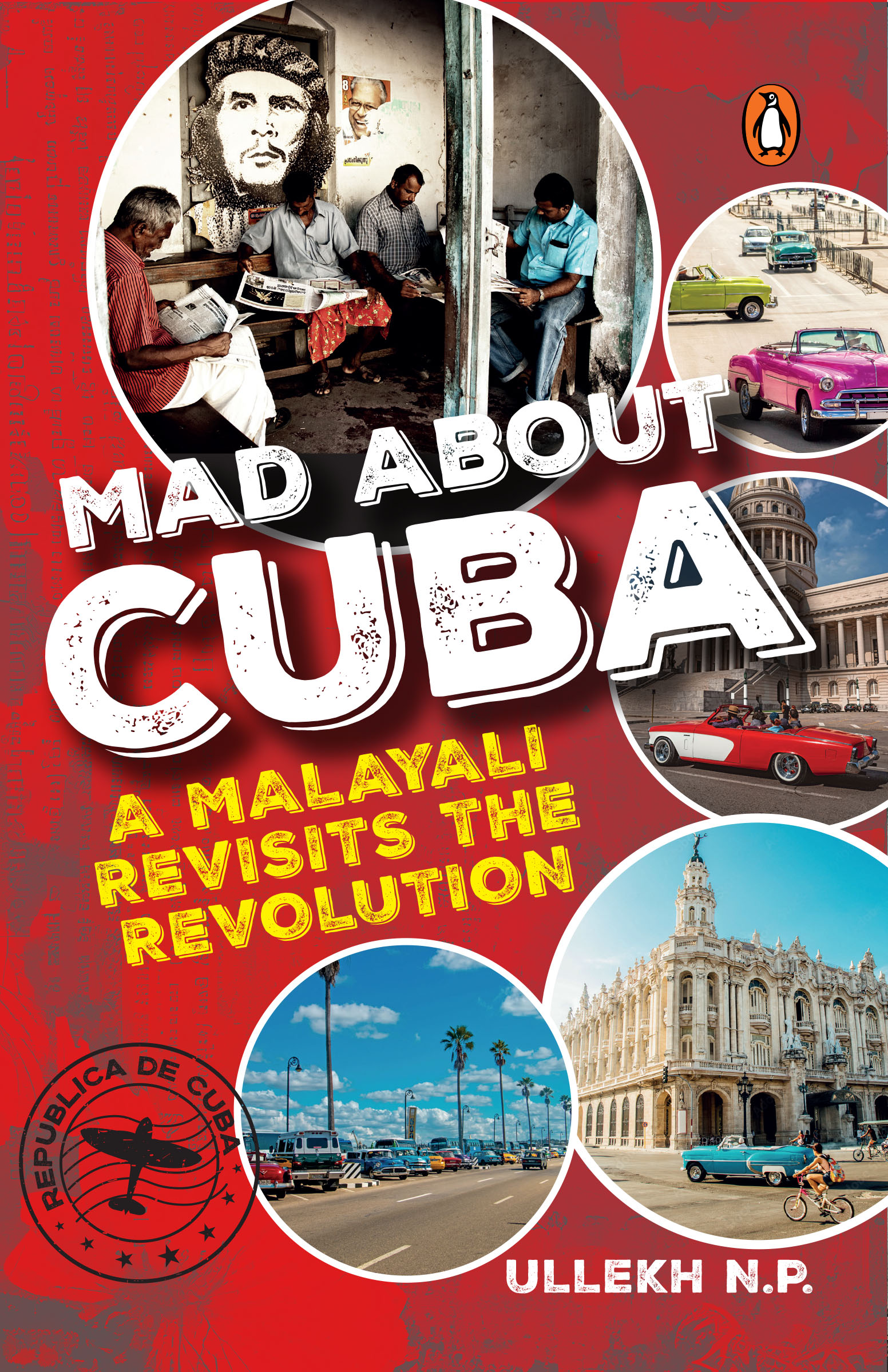

Alberto Korda’s iconic “Guerrillero Heroico” photo of Che Guevara. (Adam Cuerden – Minerva Auctions, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Cubans have always understood the range of Guevara’s brilliance and gumption, and scholars around the world are now gradually opening new doors of perceptions for those (including me) who had wrongly concluded that we had demystified Che Guevara and his passion. Such relatively new academic studies not only shine a light on a rare breed of leader but also diminish systematic and coordinated attempts by a section of Cubanologists to trash him through unverified, sensationalist narratives.

In Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (Grove Press, 1997), Guevara’s biographer Jon Lee Anderson quotes a journalist as saying, ‘If he entered a room, everything began revolving around him . . . He was blessed with a unique appeal . . . He had an incalculable enchantment that came completely naturally.’

Richard Gott recalls the moment in October 1963 when he first met him: ‘Guevara had a charismatic attraction in real life, long before he became a Mantegna icon in death and a hypnotic image on a pop art poster in the age of Andy Warhol. Like Helen of Troy, he had an allure that people would die for.’

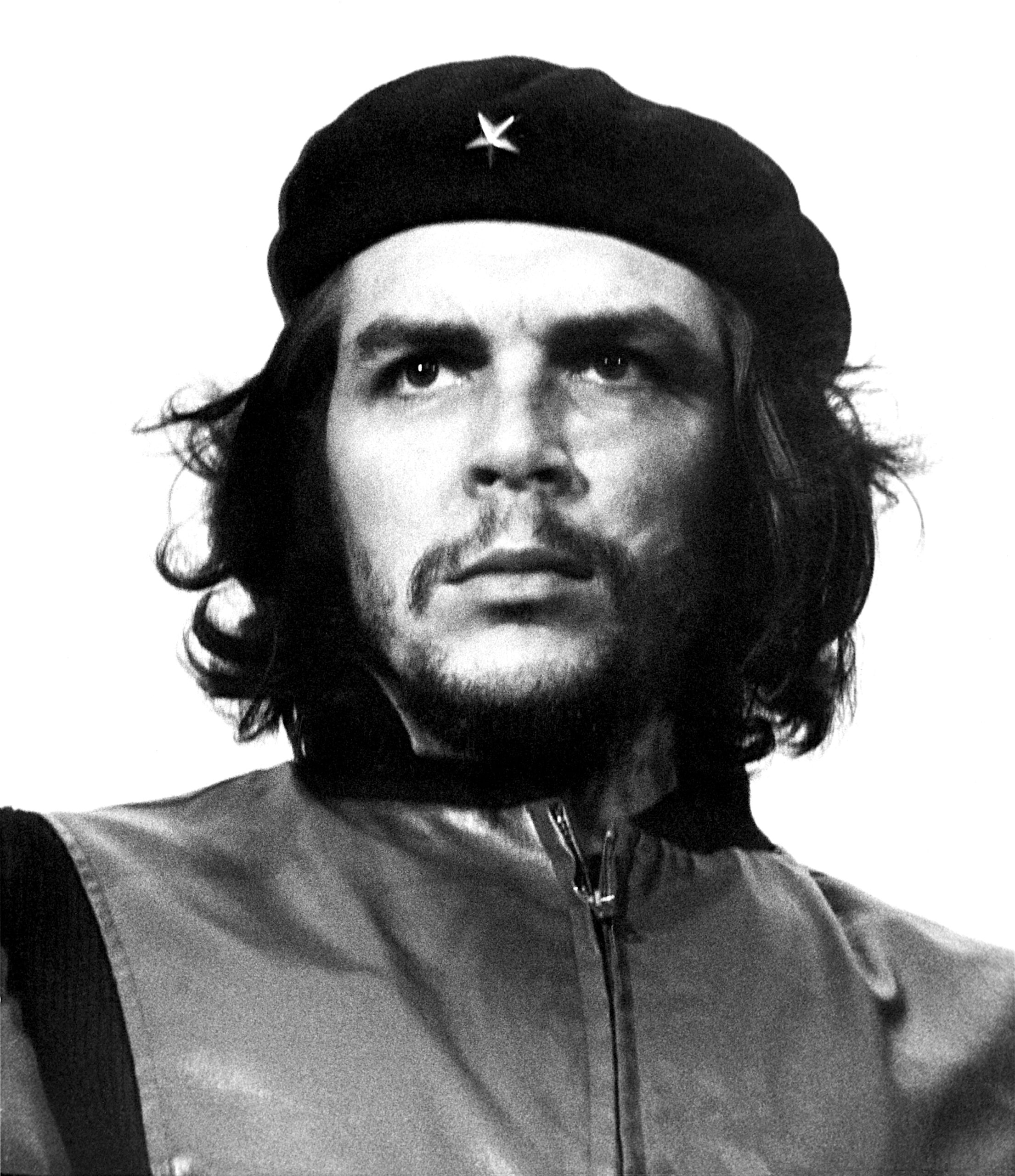

Gott was in Bolivia, in the village of Vallegrande, four years after he first met Guevara. It was at the airfield here that Guevara’s body was brought in a helicopter from La Higuera, the Bolivian village near where he was held by C.I.A. and local operatives before being executed. Gott was one of two men (besides a Cuban-American C.I.A. operative) who identified the body that lay with open eyes as Guevara’s — because they were the only ones who had met him before.

Guevara’s corpse before being tied to the landing skids of a helicopter and being flown from La Higuera to neighboring Vallegrande, Bolivia, in photo taken by covert C.I.A. operative

Gustavo Vizilloldo. (C.I.A., National Security Archive, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

That moment perhaps changed many people’s romantic ideas about an armed guerrilla revolution. It certainly did in Cuba where Fidel Castro soon began to throw his weight with greater vigour in favour of the Soviet Union and distance himself from genuine protests against the socialist empire from its constituents in Eastern Europe.

Regardless, Guevara has many more claims to fame and continued relevance than being a mere guerilla leader and a military theorist.

That day, having gorged endlessly on Guevara, I checked out the Bocoy Rum Factory, run from a typical rundown Cuban building in the Cerro neighbourhood. Not a single plaque or hoarding from the pre-revolutionary era has been removed. There are several framed photos of Che, Camilo and Fidel with cigars. This outlet is an attraction among tourists for its shop on the second floor that sells cigars, coffee, and rum — after all, Bocoy is the maker of the iconic Legendario brand of rum. You can also buy knick-knacks here. I buy a few cigars and order their coffee. It is amazing to watch the portly middle-aged man behind the counter prepare it. He makes it the way Keralites make adicha chaaya (frothy tea) from a samovar by lifting the container high up and letting the hot liquid fall into the cup below.

But this coffee is altogether something else — it is a bright blue liquid flame. I am sure it is tougher to make this coffee than adicha chaaya. The barista does it with the composure of a magician who knows his audience will be shocked by his skills. And I am. I dutifully make a video of the spectacle like a quintessential tourist.

Flaming coffee, Havana. (Tony Hisgett, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The coffee he makes is, without doubt, the best one I have had outside of western Tamil Nadu 9 (in south India). For a moment, I don’t feel the need to have my rum cocktail at night. The flavour of coffee stays with me like a moveable feast, but I am made of sterner stuff, and there is no way I will let a Cuban evening go to waste. As the Cubans say, Disfruta la vida! (Enjoy life). Tonight, I will have my daiquiri until I am spiritually satiated.

Fighting Poverty

Since the Special Period, Cubans have found a way to fight poverty. While tales around Cuban men and women taking to prostitution (female sex workers are called jineteras in Cuba and the males jineteros or pingueros) are a common source of chatter among tourists who often brag about their conquests after returning home, many enterprising locals started running home kitchens to make extra income.

Although not legal, these micro-enterprises began to thrive across Cuba, and the citizens began to get a taste of entrepreneurship out of necessity to survive the seemingly insurmountable odds of shortage and economic crisis.

Such eateries — which one enters through backstairs or rear doors — are called paladares, and are now legal. According to local lore, they got their name from a fictional home restaurant called Paladar that featured in a successful Brazilian soap opera Vale Todo (Anything Goes) on Cuban TV in the 1990s. The protagonist was an enterprising woman who had several tables in her living room, and so she decided to turn her home into a restaurant.

Earlier, paladares were intimate, homely operations — imagine walking into a stranger’s living room and having a freshly cooked meal with them for a modest charge — but many of these have now become high-end restaurants. The growth of paladares brought into the mainstream Cuban dishes and the secret cuisines of the multiple ethnicities in the country. I have had the pleasure of relishing food at some such places of gastronomical delight, including the emblematic La Guarida, which — though not as homely as paladares used to be — is still quite an experience.

Please Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!![]()

As the saying goes, there are two kinds of tourists in Havana: those who have been to La Guarida and those who haven’t (I would say that about many other eateries too). Famous for its celebrity clientele, lively atmosphere and delicious food, its presence in a rundown residential neighbourhood only adds to its exotic charm. Ranked high on most restaurant rating websites, it reminds me of the happy buzz at most Colaba joints in Mumbai on Saturday nights. The pricing at La Guarida, however, is out of reach for most locals in Havana.

La Guarida, Havana, 2009. (Bruna Benvegnu, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Exposure to the good life among a section of the population, especially in urban centres, means people have become more aspirational than they used to be — that is the feeling one invariably gets in Cuba. Isn’t it human nature after all? Although she didn’t express it in as many words, I sensed that my interpreter Gabriela was discontent with the growth prospects in her career. One doesn’t have to spell it out or talk in a complaining manner to give such an impression. A gesture here, a gesture there, that is enough to decode what young people think of opportunities in their country.

Politically conscious and smart, Gabriela is an artist with words. She is thorough with her work and her job skills are admirable. She speaks excellent Spanish, English and French. And she is enormously attentive. Why wouldn’t a young linguistic expert like her crave lucrative job prospects?

Having once picked her up from home — which was in the low-income neighbourhood of Lawton in Havana — on my way to interviews with officials, I couldn’t help but admire how, in a short period (she finished college in December 2022), she had become a high-class professional working with senior government functionaries. Generally, she comes across as an extremely intelligent and driven person.

Most of her classmates have left the country and are looking for jobs abroad, she tells me. I ask her — although I shouldn’t have — how much she earns in her job, and I feel sad on discovering that she is grossly underpaid. She has stayed back in Cuba for the time being. But who can blame her if she decides in the future to relocate elsewhere, fully prepared to struggle to find a well-paying job?

When the country wasn’t as consumerist as it is now, it would have been easier to stay proud of what you do and about your country, whatever be your take-home paycheque. But no longer. We all understand human behaviour in an unequal society, and I am sure the government in Cuba understands that too. Which was why reforms have been continuous since the early 2010s under Raul Castro (who took on the mantle from older brother Fidel in 2008 and relinquished the post of president of Cuba 10 years later).

Obama, center, and Raul Castro, right, at the Palace of the Revolution in Havana, 2016. (White House, Pete Souza)

It is likely that he knew it was an unhappy situation. After a round of success with Obama, however, Cuban hopes of normalization of ties with the U.S. hit the skids when Trump won. Elimination of extreme poverty and access to free universal healthcare and education can only take Cuba this far amidst the economic strangling by the West.

Humans are hardwired to chase their desires. No force on earth can kill that urge to break free. Several questions arise now. Is Cuba pragmatic enough to steer through a transition by exploiting the market economy for its own good? Will the communist party feign loosening the strings and allow for reforms to dramatically improve the economy and then tighten its grip as China is doing now?

Ricardo Alarcon

There are enough indications that the Cuban communist party isn’t falling off the guardrails yet. After all, the late Cuban revolutionary and top official Ricardo Alarcon, the political guru of several communist leaders, had taken several steps to ensure that the new generation, that is more adept and quicker at making decisions, would be in charge.

Gott has written about this in Cuba: A New History before, saying, ‘Far from being controlled by veterans of the Revolutionary War, Ricardo Alarcon claimed in 2001 that the majority of people in the government and the Communist Party are under forty.’ Preparations had been on, for sure, to keep pace with the changing times. Havana-based historian Dr. Sergio Guerra Vilaboy tells me:

‘The legacy of Ricardo Alarcon de Quesada is that of ethical diplomacy, attached to international standards and committed to the defence of his country and institutions. His opinion was precious to the Cuban government in decision-making. But he was particularly radical in matters that had to do with relations with the United States, a topic in which he became the first Cuban specialist, which explains the trust placed in him by Fidel Castro.’

Vilaboy, author of Cuba: A History, adds that Alarcon continued to be consulted on everything related to relations with the United States until his final years.

Surviving the Blockade

“Let’s continue defending the revolution” on wall in Havana, 2017. (Laura D, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

One doesn’t need to master nuances of political theory to comprehend that this is a country in transition that still braves the blockade thanks to sheer willpower and ingenuity. Dr. Helen Yaffe tells me, ‘Right now, the big challenge in Cuba is how they can survive the suffocating blockade and how they can continue to keep the lights on, people fed, hospitals supplied and so on in the context of the tightened sanctions and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.’

To the specific question on wage disparities, she quips, ‘This issue of wage differential in Cuba dates back to the 1990s — I discuss it in my book We Are Cuba: How a Revolutionary People Have Survived in a Post-Soviet World. You are asking about rich Cuban Americans splurging money in Cuba but — at a point when Trump and Biden have pounded Cuba with sanctions —coercive measures have slowed the flow between the U.S. and Cuba to a trickle.’

Miami ‘Exiles’

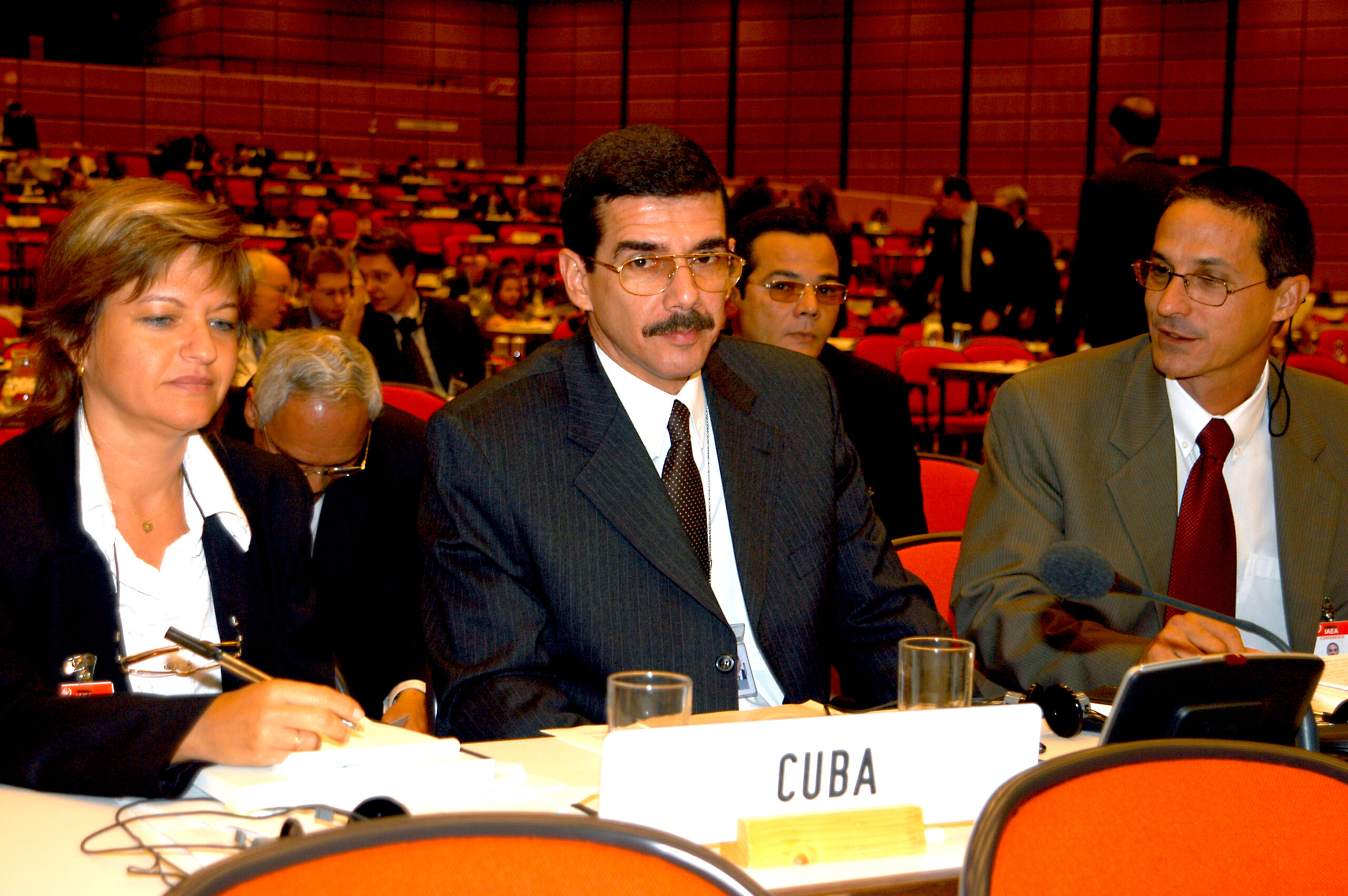

José Ramón Cabañas Rodríguez, popularly known as Ambassador Cabanas (he was the first Cuban ambassador to the U.S. in 54 years when he was named to the post in 2015, a stint that lasted until 21 December 2020), and I met at his office at the Research Centre for International Policy (CIPI) where he is currently the director. The institute falls under the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

I was late from a previous meeting and so I was glad that he too was late. He walked in apologizing profusely for being late, although his secretary had alerted me in advance. Cabanas possesses the aura of a diplomat who knows you the moment he looks at you, like some kind of a mind reader. It took me several minutes to regain my composure under his knowing gaze.

Cabañas, who rarely gives interviews, is trained to listen to questions attentively. He doesn’t jump to respond until you are fully done with your questions. In fact, he waits close to 10 seconds even if you have finished your question to allow for a pause or for the impact of your question to sink in. This quality of his as a top-notch diplomat — to not only listen but also to assess the person raising the question — is widely known among other Cuban officials who are familiar with his style.

I asked him about western Miami where Cuban exiles — and politicians from among them —form the most stringent critics of the Cuban experiment. He busts the perversely counter-intuitive declarations by Cuban Americans in their early years in the U.S., having fled Cuba after the Revolution: that they were hounded out because they were bourgeoisie who owned sugar mills and big businesses. Cabañas joked, ‘If so many people had sugar mills, then Cuba was a land full of sugar mills and the archipelago wouldn’t have had the space to accommodate them.’

He also argued that whenever you look for a job in the U.S., what sells is the story of victimhood. And when you are asked to fill out forms asking whether you stand for or against Cuba, the exiles, who know well the inimical relations between Cuba and the U.S., would never hesitate to choose which side of the bread is buttered.

‘Many naïve journalists have made a living selling the so-called misery of Cuban Americans without realizing that political game plans also had a role in perpetuating this myth, although it cannot be said that there weren’t genuine cases among Cuban emigres. But one-sided narratives of the Cuban Americans’ plight are rampant in the U.S. and, as far as I could gather, among foreign correspondents who are forever ready to buy this story,’ he said in his deep baritone.

He went on to add that people ‘lying to impress their constituency’ have been caught in the act. For instance, Senator Marco Rubio was called out by The Washington Post for ‘embellishing’ his family’s story by saying his parents left the island after Castro came to power while, in fact, they had left it before the Cuban Revolution of 1959.

According to reports from 2011, he had claimed on his official website that he was ‘born in Miami to Cuban-born parents who came to America following Fidel Castro’s takeover’. He had also campaigned in 2010 stating that, ‘As the son of exiles, I understand what it means to lose the gift of freedom.’

Cabañas at an IAEA conference in Vienna in September 2002. (Dean Calma /IAEA Imagebank, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

According to the Post report, Rubio’s parents had left Cuba in 1956 during Batista’s period for economic reasons. Rubio’s website now makes no such claims and instead says the following:

‘Marco Rubio was born in 1971 in Miami, Florida, as the son of two Cuban immigrants pursuing the American Dream. His father worked as a banquet bartender, while his mother split time as a stay-at-home mom and hotel maid. From an early age, Rubio learned the importance of faith, family, community and dignified work to the good life. Rubio was drawn to public service in large part because of conversations with his grandfather, who saw his homeland destroyed by communism.’

Similarly, Rafael Cruz, father of American politician Ted Cruz, a trenchant critic of any rapprochement between Cuba and the United States, was an opponent of the Batista regime and migrated from Cuba to the U.S. in 1957.

In her 1987 work titled Miami, Joan Didion skilfully captures the relationship between Cuban exiles and Washington, D.C. She uncovers the way Cuban exiles were manipulated by the C.I.A. and drawn into conflicts in Latin America. She began to focus on Miami after noticing the names of Cuban and Latin American dissidents in the Kennedy assassination hearings of the late 1980s. While they were at the forefront of the failed Bay of Pigs attack, the Watergate wiretapping scandal, and so on, they were also indicted in the Oct. 6, 1976. terror strike on the Cubana de Aviacion Flight 455 from Barbados to Jamaica.

One such Cuban exile was Luis Posada Carriles. He not only helped organize the Bay of Pigs Invasion, but was also implicated in a series of bombings in Cuba after becoming an agent for the C.I.A. The National Security Archive in 2006 posted on their website about

‘… new investigative records that further implicate Luis Posada Carriles in that crime of international terrorism. Among the documents posted is an annotated list of four volumes of still-secret records on Posada’s career with the C.I.A., his acts of violence, and his suspected involvement in the bombing of a Cubana flight, which took the lives of all 73 people on board, many of them teenagers.’

Cabañas reiterated that most Americans favoured the lifting of American sanctions, and even the majority of Cuban-American exiles weren’t vehemently opposed to the easing of American sanctions on Cuba. He cited as evidence the Florida International University’s (FIU) Cuba Poll, which was first conducted in 1991. The poll, says FIU, is the longest-running research project tracking the opinions of the Cuban-American community in South Florida. It is directed by Dr. Guillermo J. Grenier and Dr. Hugh Gladwin, faculty members in FIU’s Department of Global and Sociocultural Studies. The poll is designed to measure the views of Cuban Americans about U.S. policy options toward Cuba.

Some of the highlights of the latest survey available (2020) are interesting. While ‘the older respondents, the pre-1995 migrants and registered Republicans’ are supportive of isolationist policies and attitudes, ‘the younger respondents, Cuban Americans born outside of Cuba, and registered Democrats are supportive of engagement policies’.

It adds that among those who have migrated after 1995 to the U.S. from Cuba, 76 percent have travelled back to Cuba, while that number is 40 percent among those who migrated before 1995. Quite surprisingly, the survey states that 62 percent of the total respondents want airline services to be re-established in all parts of Cuba.

Cabañas noted that many Americans — Cuban-origin or otherwise — are interested in visiting Cuba: ‘They don’t care about socialism. They want to travel and do business. They want to send in remittances. They want to buy property.’ He said that when he was head of the consulate service in the U.S. (2012 to 2015), 75,000 unaccompanied children travelled from Florida to Cuba as a precursor to the thaw of 2015 to 2017. ‘Don’t tell me you send kids to a country that you are at war with,’ Cabañas asserted, emphasizing that notwithstanding the American propaganda and hardship caused by the blockade, people who travel to Cuba see for themselves that Cuba isn’t the Cuba they were told it was.

The most remarkable example is Antonio R. Zamora, author of the 2013 book, What I Learned About Cuba by Going to Cuba, which is based on his close to 40 trips to Cuba from Miami. Zamora has a strange political background. Born in Havana in 1941, he left for the U.S. in 1960 and later took part in the failed invasion at the Bay of Pigs along with other Cuban exiles. He was caught and put in a Cuban jail until he was released after a deal with the U.S. in 1963. He became a U.S. Naval officer and later a lawyer. In 1995, he returned to Cuba to study the country at close quarters. That’s when he discovered that his earlier impressions of the country were far from the reality he experienced firsthand.

There was, of course, another trigger for the U.S.–Cuba detente to unravel as early as October 2017: a phenomenon that came to be called the Havana syndrome. The symptoms of this ailment, which seemed to have affected several people at the American embassy in Havana, included ‘a constellation of physical symptoms including ringing in the ears followed by pressure in the head and nausea, headaches, and acute discomfort’.

A year later on Oct. 3, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said the country was pulling back many members of its heavily fortified embassy — sort of an impenetrable fortress along the Malecon — and also expelling 15 Cuban diplomats from the U.S. over Cuba’s ‘failure to take appropriate steps’ to protect American personnel in Cuba who had been targeted in mysterious ‘attacks’ that had damaged their health.

The knee-jerk American argument from the beginning was that the physical discomforts were caused by a sonic attack by enemies. Although Cuba protested that Washington was discounting science in this accusation, the Trump administration went ahead with its plan to snap ties with the Caribbean country.

Seven U.S. intelligence agencies did a years-long investigation in more than ninety countries, including the United States, and finally concluded that it is ‘very unlikely’ that a foreign adversary was responsible for the ‘Havana syndrome’, which had affected American diplomats and other officials in many parts of the world.

But by then, all the damage was done and Cuba had to face multiple jeopardies that pushed its economy to the brink.

Ullekh N.P. is a writer, journalist, and political commentator based in New Delhi. He is the executive editor of the newsweekly Open and author of three nonfiction books: War Room: The People, Tactics and Technology Behind Narendra Modi’s 2014 Win, The Untold Vajpayee: Politician and Paradox and Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics. His book on Cuba, Mad About Cuba: A Malayali Revisits the Revolution, part travelogue and part political commentary, was released in November 2024.

Views expressed in this article and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!![]()

Make a tax-deductible donation securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

It is sad and painful to think of the cruelty our government heaps on the Cuban people.

I don’t give a shit about what any country in this world chooses as their social, economic, political structure. Why is it my business or anyone else’s business. Each culture deserves respect and admiration too.

Who is responsible for deciding the worth of another human being? Or their choice in how they live, as long as they do not hurt others.

I will never respect my own government as long as they scheme to put down and abuse others.

“In her 1987 work titled Miami, Joan Didion skilfully captures the relationship between Cuban exiles and Washington, D.C. She uncovers the way Cuban exiles were manipulated by the C.I.A. and drawn into conflicts in Latin America. She began to focus on Miami after noticing the names of Cuban and Latin American dissidents in the Kennedy assassination hearings of the late 1980s.”

Didion kind of got it wrong here in some respects. For many of the exiles in the greater Miami area they were and still are committed anti-Castro/anti-Communist zealots, eager to go along with their masters in Washington to subvert and destabilize revolutionary Cuba.

Thanks Mr. Hunkins for your thoughtful comment. I wonder how much $$$ bribes by certain agencies in our government figures into the enthusiasm of the hatred of the zealots…just saying.

That’s certainly a part of it for some of the zealots. But one should remember, many of these zealots were recently displaced former exploiters and top one-percenters of Cuba who were none too happy to see their gravy train come to an end.

sure, makes sense….

I really hope that the spoken goals of the Brics countries – consensus, cooperation, trade (as opposed to wars and thieving) respect for borders and no country finding “security” at the expense of others’ and a mature respect for others and good will towards others succeeds in bringing humanity to a level that survival of the human race is possible.

So far greed and lust for power and hubris have put us in a troubling place :)

The US – just like israel, totally ignore any laws – international or otherwise, that doesn’t suit them. “Democracy”…’Human Rights’…the epitome of hypocrisy!!!