No regime has an unlimited supply of political legitimacy. Any government, democratic or non-democratic, needs to constantly read public opinion and to try to respond to people’s minimum expectations and demands.

Protest in Tehran’s Keshavarz Boulevard after the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody. (Darafsh, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

All is not well in Iran. The country has been undergoing an upheaval of sorts, although much of the coverage of Iran is influenced not only by the blatant agenda of the U.S.-Israeli alliance, but also the agenda of the Saudi regime.

All is not well in Iran. The country has been undergoing an upheaval of sorts, although much of the coverage of Iran is influenced not only by the blatant agenda of the U.S.-Israeli alliance, but also the agenda of the Saudi regime.

Riyadh has succeeded in coopting much of the Iranian exile opposition as it sponsors Iranian multilingual opposition media around the globe. The London-based Iran International is a Saudi network from which much of the Western coverage of Iran is derived.

There are two major factors at play in the Iranian crisis. One is a U.S.-led conspiracy which has not relented since 1979, aimed at toppling the regime. This conspiracy — like Cold War efforts to undermine the U.S.S.R. — is multi-pronged and includes Israel and the Gulf regimes.

The U.S. has neither forgiven nor forgotten that Iran was lost from the American camp after the 1979 revolution. Since Iran increased its role in the Arab-Israeli conflict, and armed and financed resistance groups in Lebanon and Palestine, the U.S. and Israel have been trying to undermine the Iranian regime.

Terrorism, sabotage and unrest have been instigated and engineered by Washington and Tel Aviv. Israel, for instance, brags in Western media about its role in murdering Iranian scientists and officials.

Iran, on the other hand, still harbors illusions that the American conspiracy can be negotiated with and that reason and diplomacy can sway the U.S. from its course of sanctions and aggression.

Recent protests in Iran, however, can’t be blamed on the U.S. alone. To be sure, the West will exploit any division or crisis in Iran to instigate – as much as it can – more trouble for Tehran.

If a country’s population is content overall, however, no outside conspiracy can undermine a sitting regime. Gamal Abdul-Nasser of Egypt, for instance, faced an international war on his government and those efforts failed. (The exception was the United Arab Republic where Syria and Egypt united under Nasser’s leadership, but also where Gulf governments of the West and the Gulf sponsored a 1961 coup to destroy the unique experiment in unity).

Egypt’s President Gamal Abdul-Nasser, seated right, signing unity pact with Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli, forming the United Arab Republic, Feb. 1, 1958. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

No regime has an unlimited supply of political legitimacy. Any government, democratic or non-democratic, needs to constantly read public opinion and to try to respond to people’s minimum expectations and demands. When the gap between people’s expectations and demands and governments’ performance and policies becomes too wide, the government faces a serious crisis of legitimacy and performance.

Elements of Political Legitimacy

The Iranian regime has enjoyed various elements of political legitimacy since it came to power in 1979.

Political legitimacy is derived there from multiple sources not limited to electoral political legitimacy where a regime is supported or obeyed because the government speaks on behalf of the majority. The crisis of political legitimacy in Brazil and the U.S., for instance, stems from the fact that the population is split down the middle allowing the losing side to question the integrity and legitimacy of any election.

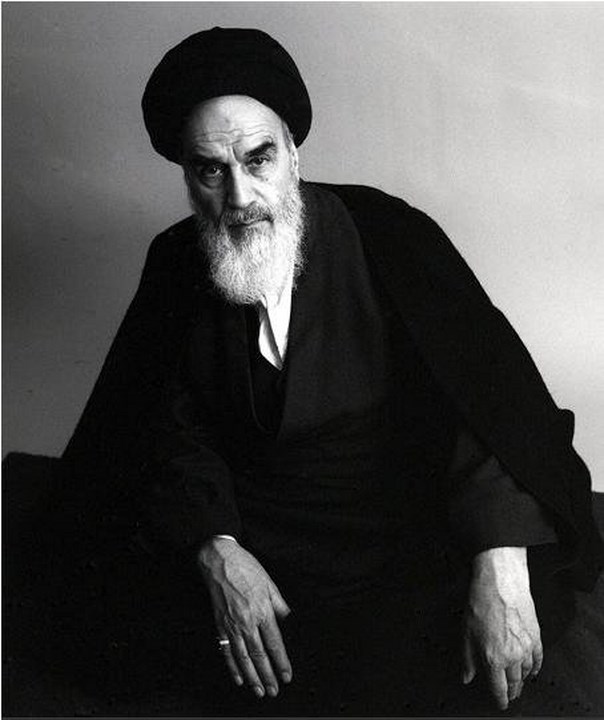

The leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini constituted the first major source of legitimacy for the Iranian regime after the revolution. Rulings and statements by Khomeini carried the religious and political legitimacy of the leader of what most Iranians at the time saw as a glorious revolution. The current office of the supreme leader is intended to draw upon the personal and religious legitimacy of Khomeini into the post-Khomeini regime.

Ayatollah Khomeini in the 1970s. (Wikimedia Commons)

With the passage of time, this source of legitimacy has lost power and appeal. Many Iranians never lived under Khomeini’s aura. He remains a historical figure but is no longer able to give the regime the same legitimacy.

The second source of legitimacy was the abolishment of the repression and torture of the Shah’s era. The Shah’s regime, as much as it was respected and admired in the West, was detested by most Iranians. Iranian opposition was the direct result of people’s insistence on ending the horrific SAVAK apparatus (which the U.S. helped set up in order to prolong the Shah’s rule and crush any opposition to it).

But the revolutionary aura waned over time as the new regime engaged in repression of its own. Most young Iranians cannot compare it to the Shah. The alternative-to-the-Shah formula of legitimacy may have worked in 1980s but no longer does today.

Shah of Iran, left, with President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office, 1973. (White House/Wikimedia Commons)

The third source of legitimacy is related to the Iranian regime’s ability to ward off external threats and aggression. Right after the toppling of the Shah, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq launched — with Western and Gulf support — an unprovoked invasion of Iran. Thinking that the regime was too inexperienced and weak to respond effectively, Saddam sought the downfall of the revolutionary Iranian government.

Far from accomplishing this goal, Iran regrouped and launched a counter offensive that could have toppled Saddam had it not been for generous Western and Gulf support. Gulf regimes may have given more than $80 billion worth of military and economic aid to Saddam.

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!

Moreover, Iran effectively used the act of foreign aggression as rallying cry for Iranian nationalism. Today, while Iran faces a sinister international (Western-Gulf-Israeli) campaign of covert aggression, the Iranian public may have grown too accustomed to this conspiracy and become too skeptical about claims of foreign intervention. The people are far more able to identify with a nationalist stance in time of war. A period of covert operations is not as useful for nationalist mobilization.

Iranian soldier in gas mask during the Iran–Iraq War. (Mahmoud Badrfar, Wikimedia Commons)

The fourth source of Iranian government legitimacy was its ability in the 1980s to chart a third course, which was independent from both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. The time of Cold War rivalry is over. Iran is now solidifying its alliance with Russia in the hope of countering the international alliance against itself.

Iranian foreign policy does not necessarily appeal to the new Westernized college students in Tehran to the same degree that it once did back in the 1980s and 1990s. Consumerism and fetishism of commodities are the new global object of emulation for the youth.

Fifthly, the regime benefited from its early adherence to a regular, albeit flawed, election process. Elections are a staple of the political system in Iran and the Iranian parliament — contrary to Western media claims and assumptions — hosts vigorous debates and arguments, as does the press. But elections were never ideal: there is a special council run by the Supreme Leader which screens candidates and decides on political qualifications.

Iran’s Assembly building in Tehran. (Ataramesh, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Furthermore, the Guardians’ Council (which supervises elections) has become more stringent and narrow: only those who adhere strictly to the hardline camp are approved to run for office.

In addition, some elections have been marred with irregularities as was the case in the last election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009. The regime — or any regime — may rig elections but by doing so it loses a major source of political legitimacy.

Lastly, the Iranian president, Ebrahim Raisi, was elected as a favorite of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. He ran on a platform of “virtue” and the imposition of Islamic standards — or the regime’s definition of those standards. The president empowering the morality police to punish violators of the hijab code sent a message about the regime’s priority at a time of great economic distress.

For people in Iran, the country contrasted favorably with the governments of the Gulf. Recent changes in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere, as far as women and Islamic standards are concerned, have worsened the image of Iran, among Iranians themselves.

If Saudi Arabia (which is still more repressive than Iran) was able to remove the dress restrictions on women and able to loosen social restrictions, then surely Iran can do the same, especially if it does not want to be seen as more backward socially than Saudi Arabia.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004) and ran the popular The Angry Arab blog. He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!![]()

Donate securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

This was published yesterday by the Al Mayadeen news agency :

Meta allows targeted hate speech, violence, but only against US rivals

US tech giant Meta announced on Monday that it now permits sharing posts calling for the death of Iran’s leader Sayyed Ali Khamenei.

The decision overturns an earlier policy to ban such posts, with Meta claiming that the phrase “Death to Khamenei” does not entail a literal threat against his life.

Users can now liberally use the phrase in English or Farsi, without violating the company’s policies and risking penalties.

“It is a rhetorical, political slogan, not a credible threat,” the Facebook parent company said in a statement.

The new policy contradicts Meta’s terms that prohibit users from promoting violence.

Furthermore, the decision comes despite all US social media platforms insisting that they practice “responsible” censorship in combating posts that contain misinformation and provoke violence, threats targeting individuals or groups, or “hate speech”.

However, this is not the case when it comes to entities and individuals that don’t align with the US foreign policy, i.e. anyone who opposes the US and its illegal hegemonic actions around the world.

According to American “free speech” policies, calling for support to countries facing Western aggression, such as Palestine, Yemen, Syria, Iran, or Russia, is a violation, which entails bans and suspensions from American-owned social media platforms.

“…there is a special council run by the Supreme Leader which screens candidates and decides on political qualifications.

Furthermore, the Guardians’ Council (which supervises elections) has become more stringent and narrow: only those who adhere strictly to the hardline camp are approved to run for office.”

We are so much better than the Iranians because we have two of them – one is called the DNC and the other is called the RNC, both of which are under the control of the elite.

Your article on Iran’s current difficulties compares very well with an article on that subject I read on Counter Punch+. The Counter Punch article was full of emotional propaganda vs Iran’s leaders. That article alone convinces me that CP+ now means “Counter Punch + US propaganda”.

“Consumerism and fetishism of commodities are the new global object of emulation for the youth.”

Perhaps that best explains the Islamic leadership’s morality policing via female dress codes. The distinct difference of appearance, of dress, is a constant reminder of the separation from the consumerist narcissism of the west. Make no mistake, the US is the prime force dedicated to destroying the Islamic Republic of Iran. And the US is single-minded, relentless, and insidious.

After the scarcities, the dysfunction and stagnation resulting from decades of political, economic, and military assault, consumerism doesn’t need to dwell in fetishism to have wide common appeal. It’s just the old “if you want to get along, then go along,” or more harshly framed by the Shrub ” You’re either with us, or against us.”

The Iranian leadership must feel like the fictional peoples encountering the Borg: “Resistance is futile. You will be assimilated.”

Never mind, Iran….America is planning to overthrow your government and bring you all Coca-Cola and Facebook and stuff.

And all it requires in return is American military bases, maybe some of the bio labs Ukraine used to have, and the right to asset-strip your country. A small price to pay for “western-style freedom”.

Sorry… I think the world is starting to make me cynical.

Great summary of the crucial issue of regime legitimacy, as applied to the Islamic Republic of Iran specifically. I imagine a similar analysis of the US would be instructive …

But re Iran, one source of regime legitimacy somewhat undercovered above was the revolution and the IR as a response to what was called westoxification in Iran … the concern that Iran was losing its own civilization as it rapidly tried to emulate the west in the Shah’s time. I think that was a prime mover and holder of the people’s minds in the early decades post-revolution: whatever happens, we are not stooges or copiers of the west anymore. We are our own people.

And this is part of the regime’s dilemma re the women’s hijab question now … if what gives you legitimacy is in large part an insistence on full implementation of Shia-Iranian traditionalism in the face of a modern western liberalism, then stepping back from it loses the regime legitimacy instead of gaining it the same.

What’s needed is Iran’s own liberalism, a liberalism born of the nation’s own traditions and not a copy of the western model.

W/o a doubt, “justice” in Iran is as evasive as “justice” is in The Divided $tates of Corporate America.

“When the gap between people’s expectations and demands and governments’ performance and policies becomes too wide, the government faces a serious crisis of legitimacy and performance.” (AS’AD AbuKHALIL)

For example, the legitimacy of Awhmerica’s 2020 Selection Election. Specifically, BIDEN-HARRIS raking in more votes than Barrack Hussein Ohbama.

Imagine that, Barrack Hussein Ohbama, the “ONLY” U.S., 2-Term POTUS, to effect perpetual war, 24/7, for EIGHT (8) Years. Then “gifting”all his wars to his Successor/Assassin-N-Chief, DJTrump. Who, in kind, gifted Ohbama’s wars back to BHO’s V.P., now POTUS, Joey “Patriot Act” Biden-Comma La Harris. They “GOT Another WAR!!!” US/NATO vs. RUSSIA War in UKRAINE.

“Elections are a staple of the political system in Iran and the Iranian parliament — contrary to Western media claims and assumptions — hosts vigorous debates and arguments, as does the press. (AS’AD AbuKHALIL)

In America, DEBATES, are ALL EXCLUSIVE. “ONLY,” for the Duopoly, Republicans & Democrats. Consequently, America’s Elections are NOT Fair & Square.

In fact, imo, it’s a Game of JEOPARDY. The Category is “The Decider:”

– “But elections were never ideal: there is a special council run by the Supreme Leader which screens candidates and decides on political qualifications.” (AS’AD AbuKHALIL)

For The Win, “In America’s 2020 Selection Election, WHO is Barrack Hussein Ohbama!?!?”

“In addition, some elections have been marred with irregularities as was the case in the last” umpteen America’s ELECTIONS: Bush, Gore, Nader, Ohbama, Kucinich, Romney, Hilary, Dr. Stein, Trump, Biden, Hawkins.

And, “The leadership of Ayatollahs,” in America, we call ‘em, The Supreme Court. Like the USG’s dirty, grubby, bloody tentacles, they got their bloody claws in every nook & cranny of plant, animal, & human life.

“Moreover, Iran effectively used the act of foreign aggression as rallying cry for Iranian nationalism.” (AS’AD AbuKHALIL)

LIKEWISE, in an EFFORT TO CONDITION American public opinion TO ACCEPT the BIDEN-HARRIS White House’s ESCALATION of the US proxy war against Russia in Ukraine, BIDEN-HARRIS facilitated, in The People’s House, Volodymyr “El Chapo” Zelensky’s “ASK,” for More Money for War! BIDEN-HARRIS hoping that it will generate a sense of “national unity.” AFTER, 180 $econds, “El Chapo” bolted w/$45 Million Big Ones from “The Big Guy’s” Congress.

Who’d a thunk, OUR “American” Culture of life, liberty, prosperity and the pursuit of happiness would be so f/jacked.

The BIDEN-HARRIS White House is responsible for the current crisis. BIDEN, literally, shuffles. Therefore, walking, from crisis to crisis is a physical ability he has lost!!! Consequently, the only transformation that might happen is BIDEN begins to ride a HOVER or DRIVE an ELECTRIC wheelchair b/c like his memory loss/intelligence; BIDEN’s, literally, shufflin’ from crisis to crisis. The CRISIS requires a mentally & physically FIT POTUS. Neither Joey Biden-Comma La Harris are mentally or physically fit. America is in deep $hit….

“Geez, you know it ain’t easy. You know how hard it can be. The way things are goin,” Skepticism’s replaced Trust, imo, “They’re” out to kill us.

The RESOLUTION: “Give the People What They Want! “..i.e., “A Plan To Save The Planet, is a provisional text, a draft built out of the analyses and demands of our people’s movements and governments.It asks to be read and discussed, to be criticised and developed further. This is a first draft of many drafts to come. Please contact us at

plan @ thetricontinental.org with your criticisms and your suggestions, since this is a living document. (VIJAY PRASHAD)

This document will eventually advance through our movements and our institutions, building towards a resolution at the United Nations to “SAVE THE PLANET” (VIJAY PRASHAD)

No nation-state’s perfect, that’s for sure.

Just a random thought, I can tell you what the Iranian regime did not do: it did not shoot dead in cold-blood in 2018 hundreds of unarmed Palestinian protesters at the Gaza concentration camp fence.

Thankyou for that, Drew.

That’s a summer I will never forget. I will never forget how the Israeli Defense [sic] Forces, with impunity, shot to death innocent protesters at the Gaza fence in front of a world audience. It was disgusting beyond belief, and all those savages got away with it!

It forced me to reconsider a lot of what I thought I knew about geopolitics, it forced me to read a lot more controversial material, stuff by Gilad Atzmon and some others.

Mr. Abukhalil’s take on Iran’s protests is similar to the take on Syria when the civil war started, namely blaming the government of Syrian president, Bashar Assad without realizing or accepting the critical role other players played. There is no doubt that the Syrian government was not blameless in what led to the civil war, as the Iranian government is not blameless in the recent riots. However, how one approaches the problem is critical, otherwise, the analysis at best muddies the water and confuses those who are not familiar with the situation, and at worst helps the sinister forces who brought the civil war and destruction upon innocent people.

While initially the protesters in Iran were peaceful and legitimate, within days, they turned into a well orchestrated riot mainly from the outside, including burning buildings banks, ambulances, police cars, stabbing, shooting and assassinations with the intention of “Syriacization” of Iran. And this is typical in Iran: whenever a major legitimate protest is developing it turns ugly (usually due to outside interferences). Realizing what was at play, the overwhelming majority of the protesters went home immediately. The culprits were the usual suspects along with their many right wing Iranian diaspora allies. In the meantime, the powerful pro western political wing of the state in Iran was sitting passively in the background and salivating at the prospect of getting back their loosening grip of power since losing at the presidential election.

Moreover while Mr. Abukhalil hinted at the so-called loss of Iran by the US, he failed to expand on it: namely, the sanctions, which have created a huge gap “between people’s expectations and demands and government’s performance”, as he puts it. The US is well aware of the destructive effects of sanctions, but Mr. Abukhalil doesn’t see sanctions as critical. Undoubtedly, Iran’s main problem is the 40 years of economic sanctions imposed by the US. The sanctions have had a devastating and paralyzing effect on the country with 89 million people, especially since the US left the Iran Nuclear Deal and imposed more devastating sanctions. The effects of sanctions have impacted all aspects of people’s life, economically, socially and psychologically. The three years of dealing with severe covid in the country while under the severe sanctions and loss of hope for any meaningful dialogue with the US specially among the younger generation have been devastating on the psyche of the entire population. Its results have been manifested in many ways including the recent angry protests. There is no doubt that the Iranian leadership is also to blame for its lack of flexibility in social and democratic issues, but, one must understand that is only one of many aspects of Iran’s complex political situation.

Well said Sailab. Nothing is ever as it seems. Especially in these days of mass propaganda and control.

This is an excellent and highly responsible comment that serve to complementarily amend the original article. Kudos to the writers of both.

That was a wonderfully objective and rather balanced analysis of the various strands of legitimacy that the IR Iran government faces in the emerging post-Covid period, but one that subsequently got its objectivity impaired somewhat by degressing into a highly subjective comparison of women’s dress codes in IR Iran and the Saudi Kingdom. Being a truely Islam-aspiring theocracy, with Ayatullahs leading it, Iran can’t get lax in its dress code even if its leaders wanted to because the Iranian people would take their leaders to task on that issue. The Saudi Kingdom on the other hand though under the powerful influence of religious conservatives is neither a full theocracy nor is it led by a Sunni Alim hence it has wider latitudes on dress issues for which the Saudi King bears ultimate responsibility to Saudi society and to God. The Iranian Ayatullahs are totally constrained by the Shariah laws whereas the Saudi Royals are more limited by their traditional and conservative ideologies on those issues. Traditionally Hallenism liberated Persian women from oppressive Zorastrian customs and in contemporary times it is Zio-Conism that is pretending to liberate Iranian women from allegedly suppressive Islamic norms. The Ayatullahs know very well that if overwhelming Iranian women stepped out into the streets in just their g-strings the Islamic regime would slip down too; just like the street power that gave the Shah the slip decades earlier, but would the bulk of Iranian women now step out of theirs slips just to send the Ayatullahs spinning out of power ? This remains the key question !

After a pretty fair description the writer suddenly goes off the rails in his last three paragraphs.

Please invite Prof. Mohammad Marandi to rebut this article.

You may also read this article from the Iranian Govt. website presstv… hxxps://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2022/03/14/678533/Iran-Saudi-Arabia-mass-execution-Raeisi-Velayati-human-rights-hypocrisy-Muslims-massacre

Dear Sir,

I agree with much of your opinion in this article. Only you simplify your analysis, when you compared the role of women in Saudi Arabia to the women in Iran.

I am not at all a religious person and am aware of all the deficits of the IR in terms of dealing with women. But would today refuse to compare these two countries. Women in Iran have far more rights that the women is Saudi Arabia. Women in Iran dress some very important positions in the society. To reduce all this to a simple “Hijab” is unfair and superficial.

Will be delighted to discuss these issues with you more in detail.

Sincerely yours