The depth of the militarization of the United States and the harshness of its wars abroad have been concealed by converting death into something sacred, writes Kelly Denton-Borhaug in an address to U.S. veterans on Veterans Day.

Ribbon on the wreath that U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Secretary of Veterans Affairs Denis R. McDonough lay in a ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington on March 29, 2021. (DoD, Lisa Ferdinando)

By Kelly Denton-Borhaug

TomDispatch.com

Dear Veterans,

Dear Veterans,

I’m a civilian who, like many Americans, has strong ties to the U.S. Armed Forces. I never considered enlisting, but my father, uncles, cousins, and nephews did.

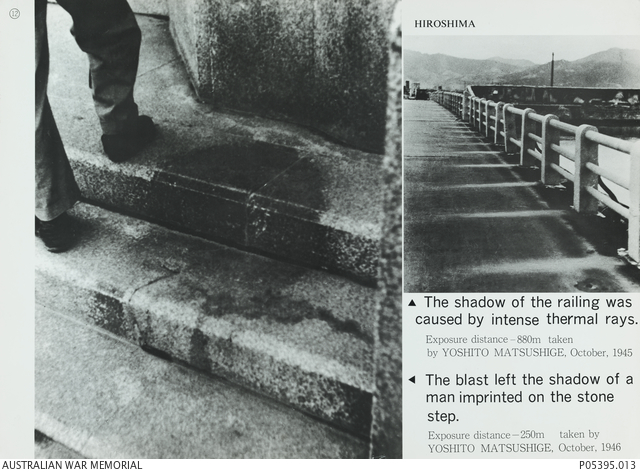

As a child I baked cookies to send with letters to my cousin Steven who was serving in Vietnam. My family tree includes soldiers on both sides of the Civil War. Some years before my father died, he shared with me his experience of being drafted during the Korean War and, while on leave, traveling to Hiroshima, Japan. There, just a few short years after an American atomic bomb had devastated that city as World War II ended, he was haunted by seeing the dark shadows of the dead cast onto concrete by the nuclear blast.

As Americans, all of us are, in some sense, linked to the violence of war. But most of us have very little understanding of what it means to be touched by war. Still, since the events of Sept. 11, 2001, as a scholar of religion, I’ve been trying to understand what I’ve come to call “U.S. war-culture.” For it was in the months after those terrible attacks more than 20 years ago that I awoke to the depth of our culture of war and our society’s pervasive militarization.

“American civilians deceive themselves by insisting that they’re a peaceful nation desiring the well-being of all peoples.”

Eventually, I saw how important truths about our country were concealed when we made the violence of war into something sacred. And most important of all, while trying to come to grips with this dissonant reality, I started listening to you, the veterans of our recent wars, and simply couldn’t stop.

Dismantling the Justifications

The only proper response to 9/11, our political leaders assured us then, was war and nothing but war — “a necessary sacrifice,” a phrase they endlessly repeated. In the years that followed, in speeches and public spectacles, one particular image surfaced again and again. The lives — and especially injuries and deaths — of American soldiers were incessantly linked to the injuries inflicted on Jesus of Nazareth, and to his death on the cross. President George W. Bush, for example, milked this imagery in 2008:

“This weekend, families across America are coming together to celebrate Easter… During this special and holy time of year, millions of Americans pause to remember a sacrifice that transcended the grave and redeemed the world… On Easter we hold in our hearts those who will be spending this holiday far from home — our troops… I deeply appreciate the sacrifice that they and their families are making… On Easter, we especially remember those who have given their lives for the cause of freedom. These brave individuals have lived out the words of the Gospel, “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” [John 15:13 ]

The abusive exploitation of religion to bless violence covered the reality of war’s hideous destructiveness with a sacred sheen. And this justification for what quickly became known as the Global War on Terror troubled me, leaving me with many questions. I wondered: Is it true that we demonstrate what we most value in life by dying for it?

What about living for what we value most?

What about living for what we value most?

Biblical stories about the suffering and death of the distinctly nonviolent Jesus of Nazareth were shamelessly manipulated in those years to sacralize our wars and the religious among us largely failed to question such bizarre connections.

Eventually, I began to understand that war cultures are by their nature death cults. The depth of the militarization of the United States and the harshness of its wars abroad were concealed by converting death into something sacred.

Meanwhile, the deaths of Afghans, Iraqis, and so many others in such conflicts were generally ignored. Tragically, religion proved an all-too-useful resource for such moral exploitation.

American civilians deceive themselves by insisting that they’re a peaceful nation desiring the well-being of all peoples. In reality, the United States has built an empire of military bases (more than 750 at last count) on every continent but Antarctica.

U.S. political leaders annually approve a military budget that’s apocalyptically high (and may reach a trillion dollars a year before the end of this decade). The U.S. spends more on its military than the next nine nations combined to finance the violence of war.

Political leaders in the U.S. and many citizens insist that having such a staggering infrastructure of war is the only way Americans will be secure, while claiming that they’re anything but a warring people. Analysts of war-culture know better. As peace and conflict studies scholar Marc Pilisuk puts it: “Wars are products of a social order that plans for them and then accepts this planning as natural.”

Learning War Is Like Ingesting Poison

I’ve personally witnessed the confusion and conflicted responses of many veterans to this mystifying distortion of reality. How painful and destabilizing it must be to return from your military deployment to a society that insists on crassly celebrating and glorifying war, while so many of you had no choice but to absorb the terrible knowledge of what an atrocity it is.

“War damages all who wage it,” chaplain Michael Lapsley wrote. “The United States has been infected by endless war.” Veterans viscerally carry the violence of war in their bodies. It’s as if you became “sin-eaters” who had to swallow the evil of the conflicts the United States waged in these years and then live with their consequences inside you.

Images from “Human Shadow Etched in Stone,” an exhibition at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, possessed by the Australian War Memorial. Photographed by Yoshito Matsushige, with a journalist’s legs included in the image on left to provide context. (Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Worse yet, most Americans refuse to face this national reality. Instead, they twist such truths into something else entirely. They distance themselves from you by labeling you “heroes” and the “spine of the nation.” They call war’s work of death the epitome of citizenship.

They don’t want to know how often and how deeply you were afraid; how conflicted you were about life-and-death decisions you had to make when no good choice was available. They don’t want to hear, as one veteran said recently in my presence, that too often your lives “were dealt with carelessly.”

They also don’t want to hear about the military training that shaped you to deal carelessly with the lives of others, both combatants and civilians. Those are inconvenient details that get in the way of a national adulation of war (in a draft-less country where 99 percent of all citizens remain civilians). After all, war fever means good business for the weapons makers of the military-industrial complex.

As Pentagon expert William Hartung recently put it, “The Biden administration has continued to arm reckless, repressive regimes” globally, while its military support for Ukraine lacks any diplomatic strategy for ending that war, instead

“enabling a long, grinding conflict that will both vastly increase the humanitarian suffering in Ukraine and risk escalation to direct U.S.-Russian confrontation.”

Such complexities involving alternatives to Washington’s war-making urges are, of course, not part of the national conversation on Veterans Day. Instead, we are promised that war and this country’s warriors will somehow redeem us as a nation.

The unimaginable losses to families, communities, infrastructure, and culture in the lands where such conflicts have been fought in this century are invisible to most citizens, while typical Veterans Day commemorations recast you as messianic redemptive figures who “have paid the price for our freedom.”

“War-culture in this country leaves us with a residual collective trauma that weighs us all down and is only made worse by a national blindness to it.”

But to convert war-making into something sacred means fashioning a deceitful myth. Violence is not a harmless tool. It’s not a coat that a person wears and takes off without consequences.

Violence instead brutalizes human beings to their core; chains people to the forces of dehumanization; and, over time, eats away at you like acid dripping into your very soul. That same dehumanization also undermines democracy, something you would never know from the way the United States glorifies its wars as foundational to what it means to be an American.

Silencing and Commodifying Veterans

U.S. Army Sergeant Osvaldo Ortiz accompanying his friend’s remains from Afghanistan to Dover AFB in June 2003. (DoD, Peter Rimar)

Meanwhile, citizens rush to “thank you for your service.” You’re allowed to board airplanes first and given discounts at the nation’s amusement parks.

Veterans Day only exacerbates your sickening commodification, as all those big box stores, other corporations, and financial institutions use you to try to increase their profits (like the bank in my town last year with its newspaper ad: “Freedom isn’t Free: Veterans Paid Our Way. Thank you. Embassy Bank”).

These dynamics silence the truths you carry within you.

I’ve heard you say that you often find it impossible to tell the rest of us, even family members, what really happened. You struggle with feelings of alienation from civilian culture, unable to express your anger or describe your struggles with deep-seated shame, guilt, resentment, and disgust.

Your military service often left you with debilitating physical and psychological injuries and even deeper “moral injuries.” Veteran and author Michael Yandell struggles to describe this ruinous self-disintegration, writing “I despaired of myself, and of the very world.”

Borne out of the crushing suffering that is the world of war, some of you experienced moral pain that grew to an intolerable level. There was no longer any world left that you could trust or believe in, no values anywhere, anymore.

And yet, you represent such a small percentage of the population — less than 1 percent of us join the military — while disproportionately shouldering such a painful legacy from the last 20 years of American war-making across significant parts of the planet.

Addiction to War

More often than not, the invisible wounds of returning veterans are shrouded in silence. For some of you, unbearable pain led to disastrous consequences, including self-harm, loss of relationships, isolation, and self-destructive risk-taking. At least 1-in-3 female members of the armed forces has experienced sexual assault or harassment from fellow service members.

Participant in a 2017 “ruck march” honoring veterans who suffer Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or have committed suicide. (U.S. Army/ Michel Sauret)

More than 17 of you veterans take your own lives every day. And you live with all of this, while so much of the rest of the nation fails to muster the will to see you, hear you, or face honestly the American addiction to war.

The truths about war that you might tell us are generally rejected and invalidated, cementing you into a heavy block of silence. Military chaplain Sean Levine describes how the U.S. must “deny the trauma of its warriors lest that trauma radically redefine our understanding of war.” He continues, “Blind patriotism has done inestimable damage to the souls of thousands of our returning warriors.”

If we civilians paid attention to your honesty, we would find ourselves slammed headlong into a conflict with a national culture that glorifies war, conceals the political and material interests of the titans of weaponry and war production, and successfully distracts us from the depth of its destruction.

We civilians are complicit and so lurch away from facing the inevitable revulsion, sorrow, mourning, and guilt that always accompany the reality of war.

An Alternative for Veterans Day

Honestly, the only way forward is for you to tell — and us to compassionately take in — the unadulterated stories of war. One Vietnam veteran vividly described what war did to him this way:

“I went to war when I was a little over twenty — not a child, but not yet an adult. When I arrived at the Cleveland airport after my tour of duty in Vietnam, I just sat down paralyzed with befuddled emotions. I didn’t even call my parents to tell them I was home. I was afraid my family would expect to see the person I was, and not accept the person I had become; that they would not forgive me for what I had done and not done in Vietnam. How could they when I couldn’t forgive myself? Like some toxic virus morphing in a Petri dish, the war infected my moral DNA. I came home no longer thinking with the same mind, seeing with the same eyes, hearing with the same ears.”

When you speak out and tell truths this way, you exemplify the epitome of citizenship, as well as courage, vulnerability, and a commitment to hope. Such revelations show that the light of your conscience wasn’t quashed by war. Thích Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist international peace activist, pointed the way forward for veterans and the rest of us alike when he wrote:

“Veterans are the light at the tip of the candle, illuminating the way for the whole nation. If veterans can achieve awareness, transformation, understanding, and peace, they can share with the rest of society the realities of war.”

The resulting trauma from war’s inevitable dehumanization is not yours alone. War-culture in this country leaves us with a residual collective trauma that weighs us all down and is only made worse by a national blindness to it.

As a civilian on Veterans Day, I hope to support the creation of spaces where your voices resoundingly are heard, and your faces seen. Together, we must determine how best to do the work of rehumanizing our world. Jack Saul, from the International Trauma Studies Program, reminds us that listening is “deeply humanizing” because it generates the healing power of empathy. Compassionate listening spaces “strengthen our connections to others and ourselves, and ultimately make society better.”

This Veterans Day I’m taking part in a “Community Healing Ceremony” through the Moral Injury Program in Philadelphia where I and other civilians will witness the strength of veterans offering testimony about the evil of war in their lives.

Hearing your words will clarify my own understanding, vision, and resolve. Listening can be transformative, helping tear down the deceitful myths of war-culture, while building honesty and a willingness to see our world as it is.

Kelly Denton-Borhaug, a TomDispatch regular, has long been investigating how religion and violence collide in American war-culture. She teaches in the global religions department at Moravian University. She is the author of two books, U.S. War-Culture, Sacrifice and Salvationand, more recently, And Then Your Soul is Gone: Moral Injury and U.S. War-Culture.

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

I’m not expert on anything.

I was looking at UCLA recently:

hxxps://www2.law.ucla.edu/volokh/beararms/statecon.htm

“Kansas: A person has the right to keep and bear arms for the defense of self, family, home and state, for lawful hunting and recreational use, and for any other lawful purpose; but standing armies, in time of peace, are dangerous to liberty, and shall not be tolerated, and the military shall be in strict subordination to the civil power. Bill of Rights, § 4 (enacted 2010).”

Standing armies in time of peace are a threat to the people. Civil power is captured by the profit motive of the MIC, so there can be no peace, or some states would have a very good case to reject any participation in the US military on constitutional grounds.

Is a “well regulated militia”, where that phrase appears, supposed to exist instead of a standing army? Rather than a globe-spanning, violent, imperial, militarist rogue state?

I’m not being rhetorical, I would like help in understanding.

I don’t think the people of the US realize how their state is viewed in most of the world. Pity, fear and condemnation spring to mind first, but be assured the people are viewed with pity, and the state is viewed with fear and condemnation. I guess Hollywood tries to shift this perception to glorify violence, both patriotic and individually righteous, and that’s a large reason people still sign up to die in someone else’s country for the profit and power of plutocrats they “know” are corrupt liars. It’s a helluva thing to watch. Heartbreaking.

It is why we need the troops to voluntarily stand-down, to “strike”, to refuse orders to go and fight in the current resource/corporate wars. And we need all civilians to stand with them. How else will it stop? How else will the psychopathic generals and armchair-warmongers be made obsolete? We needn’t worry about a strong defense, we have that. Why are so many incapable of imagining a better world than this?

Excellent article – we need many more like this to help people understand the true nature of the war addiction and its toxic and poisonous effects on so much of the human race, particularly the North Americans.

How can anyone suggest that any good can come out of war? That it is in some way a good thing to do for those on your side of the conflict – to hurt, maim and kill those on the other side. Particularly when it is your side that provoked and started the war. What kind of twisted sick mind can suggest such a thing?

Imagine if all that money and effort were put to good use making the planet a better place and helping those in need!

We would live in heaven rather than hell.

Compassion and insight, beautifully expressed. Thank you.

My family has a military history too, Kelly. I’ve learned that the very essence of Armies of all kinds is waste…waste of lives, resources, time and entropy – that is not getting any benefits from the disorder they create.

Saying that “lives were endangered carelessly” means it is purposely practiced to instill fear, and to show “who’s boss”. This indifference is carried over into the economy in the early 20th Century by, say, Thorstein Veblen’s Theory Of The Leisure Class which strutted around with their swagger sticks…think of current CEOs 400x salaries.

We can’t afford this kind of waste anymore, if we ever could.

Great article.

Yes, I went through all that after 27 months plus one day’s combat duty in Viet Nam. The young man who went over there died over there. I am not the same person. But after all these years since, there is still nothing that sticks in my craw like “thank you for your service” and “Freedom isn’t Free: Veterans Paid Our Way,”

It wasn’t “service.” It was involuntary servitude. And we certainly didn’t fight for our freedom; we fought for the American Empire and the military-industrial complex. The summary of all the wisdom I attained there is, when you find yourself part of an invading army fighting patriots, it’s time for a reality check on your worldview.

Hope y’ all got this right, Paul certainly did. In fact he hit it out of the park!

Well said!

I once saw something on the History Channel that showed how far towards militarism America has journeyed.

The show was about WW2, which back then was not unusual. The hook for this show was that it had early color films of these events so often seen in black and white. What was striking was an episode on how America had to recruit and train an Army after Pearl Harbor.

Point 1. America had to recruit and train an Army after Pearl Harbor. Notice how different that is from today. America used to have the democratic principle of keeping its military small, and relying on militias or recruitment when America had to fight. America did not have millions of people in uniform just waiting to be used in a war.

Point 2. America had to militarize the new recruits at the start of WW2. It was striking how these people in these color films of those training camps were used to being free. They had to learn how to follow orders. They had to learn how to march in formation. They had to learn to jump when someone screamed ‘Jump!’.

In comparison to today, when almost all Americans are already militarized before they join the military. They’ve been in schools run by former officers, who were given their job as District head or Principle entirely on their military service and their vow to run things in the ‘military way’. The same with employment. Almost all Americans end up working at some point for former officers who were hired to run the business in ‘the military way’.

Watching those old color films of Americans in the 1940’s, they were from a different, non-militarized world. They had to be taught the military way, because until they joined the Army, they had actually been free citizens in a non-militarized society. They had not gone to public schools run by military officers, they had not worked for a former Major. They were free, and knew how to be free.

Thanks Kelly, here in Australia our national foundation story – imagining and creating a federal democracy from six British colonies – is completely replaced by a military myth concerning WWI and Gallipoli. The veterans returning from that war were silenced and their stories switched to a state narrative concerning democracy, liberty and valour. Our national capital, Canberra, is famously a planned city. The original plan by an American, Walter Burley Griffin, included a large open-air space aligned with Parliament House, where citizens would gather in public. His design was never built. It stands today as Anzac Avenue (ANZAC is an acronym for Australian New Zealand Army Corps, our most sacred term). The present reality is a street in a cemetery, filled on either side with mausoleums to every war Australia has waged. At the end, nearer the lake, there are spaces ready for monuments to future wars. Cars drive the avenue but I have never seen people amongst the graves. It is a lifeless place, representing the lifeless form of a society built on a war myth. The myth is indelible. No politician can expect success without deference. On the anniversary of our attack upon Gallipoli in 1915 Australians rise before dawn to attend religious services. Your depiction of Concealing Militarism By Making It Sacred is nowhere more relevant than here in Australia. Our mantra is “Lest We Forget”, and we remember only the state narrative.

Like too many US citizens my knowledge of world history, let alone US history, is stunted. Perhaps this is by design (not of my own, mind you) as our lords and masters are wont to erase and disappear all those voices that do not support and enhance the “official narrative.”

Within the last year I happened to catch a PBS documentary about the life of Reinhold Niebuhr and became curious to read him. This past Saturday (the weekend before the election) I got my copy of “Moral Man and Immoral Society” and was so enthralled by it that I finished it no more than 24 hours later on Sunday. I had to remind myself throughout that it was first published in 1932, even though the particulars of our human circumstances could easily lead one to believe it was written only recently.

It does not address the moral damage done to those that experience war firsthand, but it does have quite a lot of insight as to why warmongering is so persistently easily pursued to this very day, not only by the US, but by any national interest that might see its selfish interests served by initiating war, and how a nation’s citizens are so easily beguiled into supporting that violence.

I highly recommend this book for its insights into why the status quo is the beneficiary of so large a dose of human inertia.

I think your knowledge of American history is stunted is because the powers at be want an ignorant, submissive, and meek population. In other words, the reason they don’t teach history is because you may learn something.

We rehumanize the world by not celebrating those whose work destroys it. Stop baking cookies for people who kill, stop giving preferential treatment to those who make the world a more violent place, stop seating military members first on airplanes until their work is a work of justice, peace, kindness.

And give us back Armistice Day. The day was meant to say never again, not always and forever.

Thank you.