Survivors now believe the authorities chose to blame the IRA for Belfast’s deadliest bombing during the Northern Ireland conflict to give cover to their key security policy, Anne Cadwallader reports.

A mocked up bar front in 2011 on the spot where the actual McGurk’s Bar was destroyed by a bomb in 1971 in Belfast. (Keresaspa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The families of 15 people killed in Belfast’s deadliest bombing during the Northern Ireland conflict have won a significant court victory, overturning a discredited police inquiry and boosting their demand for a new inquest and legal action against the Police Ombudsman.

The families of 15 people killed in Belfast’s deadliest bombing during the Northern Ireland conflict have won a significant court victory, overturning a discredited police inquiry and boosting their demand for a new inquest and legal action against the Police Ombudsman.

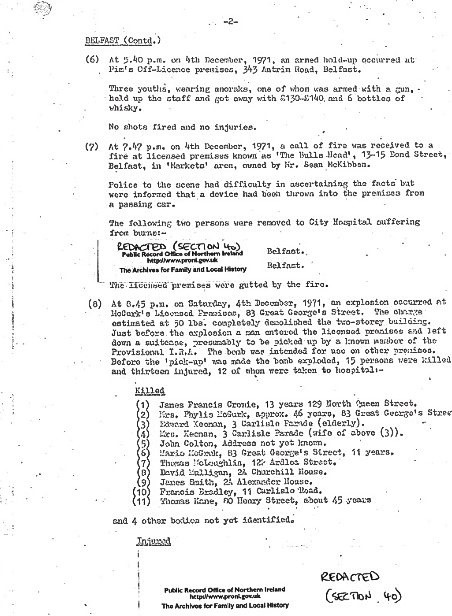

The bombing of McGurk’s Bar in Belfast on 4 Dec. 4, 1971 marked a turning-point in the rapidly worsening civil conflict. The bomb was planted by the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), and its victims were men, women and children aged from 13 to 73. Only one man was ever convicted.

At the time, the unionist-dominated government at Stormont was putting suspected members of pro-united Ireland republican groups in internment camps, against whom there was little or no evidence.

Internment was a highly controversial U.K. policy introduced in August 1971 involving the detention without trial of hundreds of people.

The families now believe the authorities chose to blame the IRA for the McGurk’s Bar bombing to give cover to their key security policy – interning suspected republicans.

The Bombing

The Bombing

The bombing took place a few weeks before Christmas. A paper-boy saw a man lighting the fuse, went over to investigate, saw sparks coming out of a “parcel” and ran off, warning a man on the street. At 8.47 p.m., the bomb detonated.

One of those badly injured was a decorated military veteran, John Irvine, a former colour sergeant in the Royal Irish Fusiliers, who had taken his wife Kitty for their usual Saturday night drink at McGurk’s Bar.

The bomb ripped through the building, bringing down the roof and trapping customers and staff under the rubble, breaching a gas main and starting a fire. Locals clawed through the rubble with their bare hands.

Irvine, who had survived World War II, was pulled out alive but his beloved Kitty died beside him.

He never recovered from the shock of losing his wife. A post-mortem examination showed Kitty had inhaled fumes from the burning building. The fire killed her as she lay in the rubble.

An ambulance driver, who was one of the first on the scene, described hearing the screams of the injured and dying. They haunted him until he died.

The owner of the bar, Patrick McGurk, was described in one official document as “a moderate RC [Roman Catholic] unlikely to have allowed people to use it as a meeting place.” He lost his wife, his 14-year-old daughter, his brother-in-law, his home and his business in the bomb.

Responsibility for it was claimed by a group calling themselves “Empire Loyalists” who had bombed a Catholic youth group a month previously.

And that might have been the end of the story, forgotten by all except the bereaved, if a group of relatives, including Ciarán MacAirt, Kitty’s grandson, had not begun digging in the official archives after the 30th anniversary of the bombing.

‘RUC Have a Line’

The key question he was determined to resolve was whether the bomb detonated inside the building — in which case the IRA “own goal” theory would be vindicated – or whether it exploded outside – in which case loyalists were the likely culprits.

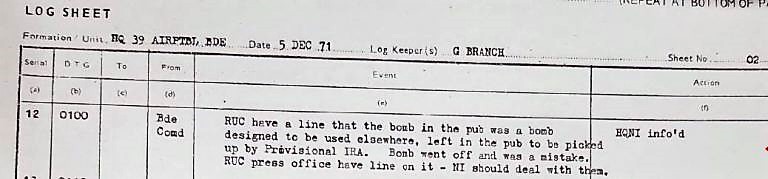

From MacAirt’s research, it is now known that within five hours of the explosion, at around 1 a.m., a note was recorded in the official diary of Brigadier Frank Kitson, who was head of the British Army’s 39th Brigade in Belfast and an experienced counter-insurgency expert from fighting Mau Mau insurgents in Kenya.

He noted that the local police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC),

“have a line that the bomb in the pub was a bomb designed to be used elsewhere, left in the pub to be picked up by Provisional IRA. Bomb went off and was a mistake. RUC press office have a line on it – NI [presumably the Northern Ireland Office] should deal with them.”

Seven hours later, at around 8 a.m., an RUC duty officer logged:

“Just before the explosion a man entered the licenced premises and left down a suitcase, presumably to be picked up by a known member of the Provisional IRA. The bomb was intended for use on other premises. Before the ‘pick up’ was made, the bomb exploded.”

The die was cast. The McGurk’s Bar victims, or some of them, were to be blamed for a premature explosion that killed 15 people.

However, at around the same time (8 a.m. on the morning after the bombing), a “Director of Operations” brief was prepared by staff officers for the general officer commanding the British military in Northern Ireland, General Harry Tuzo. It summarised what was then known about the atrocity.

This time it was the truth. “A bomb believed to have been planted outside the pub was estimated by the ATO [British Army Technical Officer] to be between 30/50 pounds of HE [high explosive].”

At 11.05 a.m., a report was made to 39 Brigade HQ, also telling the truth: “As far as can be assessed by the damage and crater caused by the explosion the bomb was placed in the ground floor entrance on the corner of the building that faced into the junction”. It added that between 40 and 50 lbs of explosives had been used.

Five minutes later, at 11.10 a.m., a report by an ATO was logged, saying “ATO is convinced bomb was placed in entrance way on ground floor. The area is cratered and clearly was the seat of the explosion. NOT FOR PR.”

That last sentence, “NOT FOR PR” is crucial as it was, in effect, an order to suppress what the ATO had found so the lie would run.

The truth would have strongly tended towards loyalists placing the bomb, intent on causing the deaths of the, assumed, Catholics inside.

Sixteen days later, however, General Tuzo — who, incidentally, was personally opposed to internment — delivered a Christmas message, implicating republicans.

The Dublin-based Evening Herald reported him saying that the forensic evidence led him to be 98 percent certain the bomb had detonated inside the building, pointing to the “IRA own goal” theory.

In a classic case of victim-blaming, the newspaper quoted Tuzo directly saying this “certainly rules out that anybody not known to the denizens of that pub could have got in with a parcel under his arm.”

Four days later, on Christmas Eve, The Guardian reported that “forensic scientists” had concluded their “grisly investigation” and “established that five men were standing around the bomb” and were “blown to pieces”. One of the five, it said, was “identified” as being “a senior IRA man who was an expert on explosives and on the Government’s wanted list.”

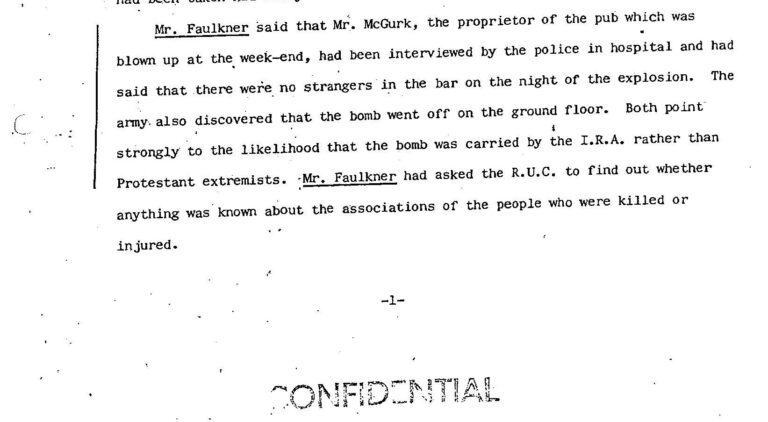

The RUC line, amplified by Kitson’s 39th Brigade log, was also passed on to the Stormont political leadership and its masters in London.

A document uncovered by the Pat Finucane Centre (for which the current author works), signed as read by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, also claimed the bomb had “gone off on the ground floor” which points “strongly to the likelihood that the bomb was carried by the IRA rather than Protestant extremists.”

Further, the document states: “Mr. Faulkner [Brian Faulkner, then Northern Ireland’s prime minister] had asked the RUC to find out whether anything was known about the associations of the people who were killed or injured.”

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Faulkner was asking the police to find incriminating evidence against the victims of the bombing.

‘Own Goal’

Tuzo, Kitson and Faulkner were not on their own. On the day after the bombing, John Taylor, then junior home affairs minister in the Stormont government (now Lord Kilclooney), told the press he believed the Provisional IRA to be responsible.

He repeated the claim in a Stormont parliamentary debate on 7 December 1971 saying: “The plain fact is that the evidence of the forensic experts supports the theory that the explosion took place within the confines of the walls of the building.”

In 2010, in the aftermath of a Police Ombudsman’s report concluding that the RUC was biased in its investigations, Lord Kilclooney refused to withdraw or apologise for his IRA “own goal” claim.

When questioned more recently, he has given either vague or contradictory explanations on where his original claim originated.

In 2018, Kilclooney doubled-down on his claims, posting on Twitter: “It was a drinking hole for IRA sympathisers who have subsequently carried out a political campaign to place the blame on the UVF”.

50 Year Fight

The truth would never have come to light had it not been for the victims’ families who have fought for over 50 years to access the declassified documents and overturn reports that they say are either inaccurate or inadequate.

Plaque commemorating the victims of the 1971 McGurk’s bar bombing, North Queen Street, Belfast. (Keresaspa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The bombing has now been the subject of two police investigations, two Police Ombudsman reports and numerous, continuing, court challenges. It was also examined by the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) — a unit that reviewed murders during the Troubles.

In 2011, a revised Police Ombudsman report identified “investigative bias” and failures in the original RUC murder inquiry. Almost immediately, the chief constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), Matt Baggott, angered the families by disputing the finding of RUC bias.

Then in 2014, the HET’s investigation also found no evidence of bias. In the recent court judgement this report was overturned as irrational and therefore illegal.

So why were the innocent victims of an appalling atrocity labelled as responsible for their own deaths? The families, and their supporters, believe London wanted to justify its decision not to intern Protestant paramilitaries and, had they been blamed for the McGurk’s Bar bombing, that would have been politically difficult.

Just before internment was introduced, Edward Heath had told Faulkner, Graham Shillington, then chief constable of the RUC and General Tuzo that: “If there was any evidence of the involvement of Protestants in any form of subversive or terrorist activity, they too should be interned” — unwelcome news for Shillington and Faulkner.

The decision not to arrest loyalists was even formalised in a Ministry of Defence memo entitled, boldly, “Arrest Policy for Protestants,” dated November 1972. This stated: “Protestants are not, as the policy stands, arrested with a view to their being made subject to Interim Custody Orders” (ie internment orders).

During the four years that internment without trial was enforced (August 1971 to December 1975) a total of 1,981 suspects were held in Long Kesh and other prison camps in Northern Ireland. Of those, 1,874 were Catholics or republicans, and only 107 were Protestants or loyalists.

This remained the case even though, by the end of 1972, loyalists had killed over 120 people. By late 1972, however, memos did begin to circulate in the Ministry of Defence and Northern Ireland Office on what circumstances they “might” arrest and intern “Protestants.”

Anne Cadwallader has been a journalist in Ireland, North and South, for the last 40 years, working for the BBC, RTE, The Irish Press and Reuters. She is an advocacy case worker at the Pat Finucane Centre, a non-party political, anti-sectarian human rights group advocating a non-violent resolution of the conflict in Ireland.

This article is from Declassified UK.

Has anyone ever surveyed who’s pulled more covered-up, dirty tricks (that we know about), the Brits or the Yanks?

Let all liars & deceivers be upended, their lips sealed from further blasphemy. Thus to abstain to speak hereafter other than with a kind of celibacy of the mind – to wish no harm to any living being.

Seems to me the same kind of objective, factual investigation should be carried out relative to the demolition of WTCs 1, 2, 7.