In a lawsuit, global pharmaceutical companies acknowledged for the first time the extent to which Mexicans visiting the U.S. on short-term visas contribute to the world’s supply of blood plasma, Stefanie Dodt reports.

Pedestrian entrance to Mexico at San Ysidro, Calif., 2020. (U.S. Customs and Border Patrol)

By Stefanie Dodt

ARD German TV and ProPublica

In the year since the United States blocked Mexicans from entering the country to sell their blood, the two global pharmaceutical companies that operate the largest number of plasma clinics along the border say they have seen a sharp drop in supply.

In the year since the United States blocked Mexicans from entering the country to sell their blood, the two global pharmaceutical companies that operate the largest number of plasma clinics along the border say they have seen a sharp drop in supply.

In a suit challenging the ban, the companies acknowledged for the first time the extent to which Mexicans visiting the U.S. on short-term visas contribute to the world’s supply of blood plasma. In court filings, the companies revealed that up to 10 percent of the blood plasma collected in the U.S. — millions of liters a year — came from Mexicans who crossed the border with visas that allow brief visits for business and tourism.

The legal challenge by Spain-based Grifols and CSL of Australia relates to an announcement last June that U.S. Customs and Border Protection doesn’t permit Mexican citizens to cross into the U.S. on temporary visas to sell their blood plasma. The suit was initially dismissed by a federal judge but reinstated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The drug companies’ lawyers have said in court filings that the sharp reduction in Mexicans selling blood to the border clinics is contributing to a worldwide shortage of plasma and is “precipitating a worldwide public-health crisis that is costing patients dearly.”

ProPublica, ARD German TV and Searchlight New Mexico reported in 2019 that thousands of Mexicans were crossing the border to donate blood as often as twice a week, earning as much as $400 per month. Selling blood has been illegal in Mexico since 1987.

Many countries place strict limits on blood donations — Germany, for example, allows a maximum of 60 donations per year with intensive checkups before every fifth donation. But the Food and Drug Administration doesn’t require comparable donor checkups and allows people visiting American clinics to sell their blood twice a week, or up to 104 times a year.

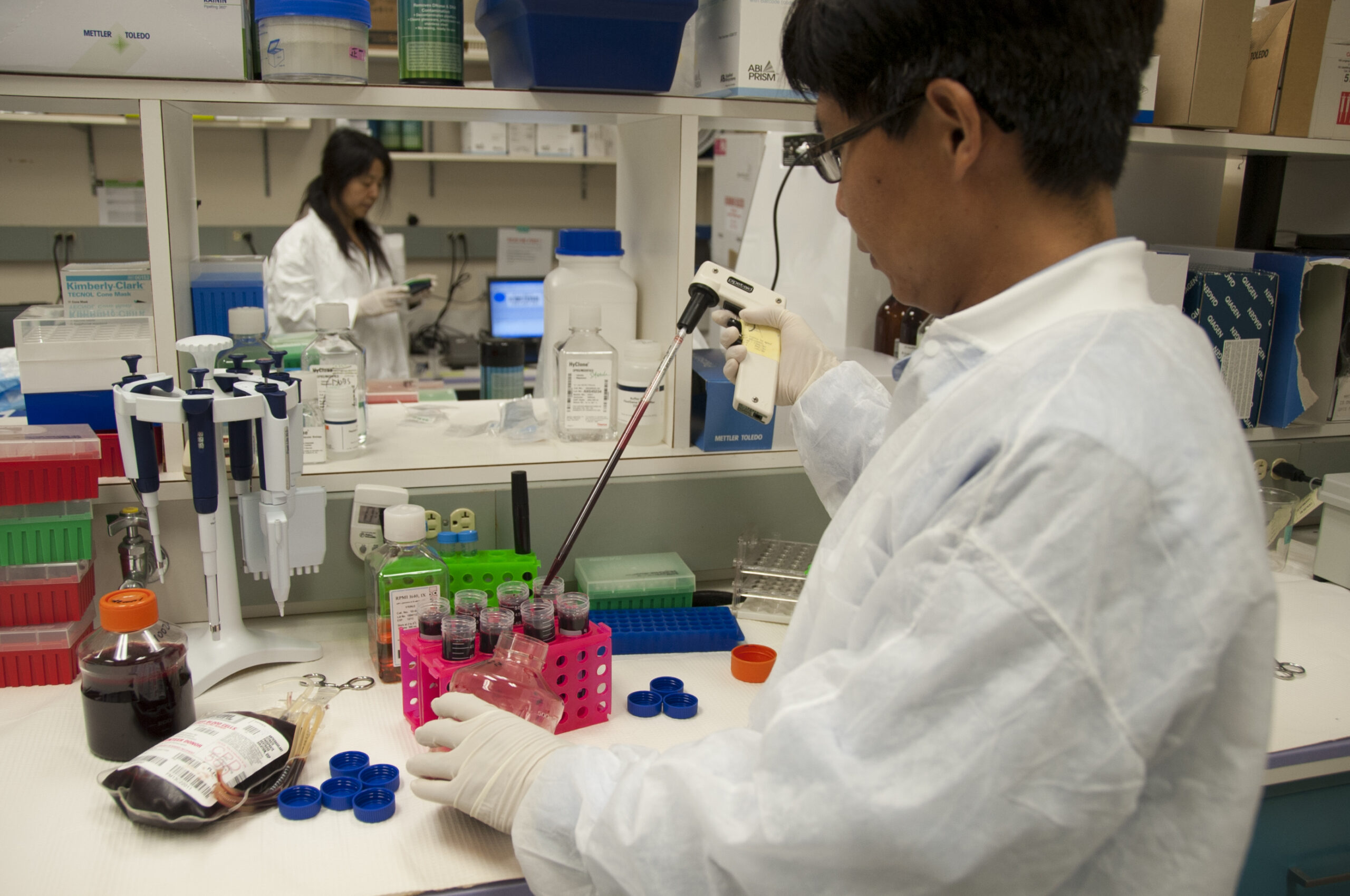

U.S. FDA scientist in 2013 prepares blood donation samples for testing. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Wikimedia Commons)

The limits that other countries set on blood donations have made the U.S. one of the world’s leading exporters of blood. In 2020, U.S. facilities collected 38.2 million liters of plasma for the production of medicine, accounting for approximately 60% of such blood plasma collected worldwide.

Until now, it has been unclear how much of the U.S. blood plasma supply came from Mexican citizens and pharmaceutical companies had downplayed border clinics’ role in meeting demand for plasma. Grifols noted in 2019 that “more than 93 percent of the centers [are] at a far distance from the border between the U.S. and Mexico.”

Border Clinics

But in its recent court filings, Grifols stressed the importance of the border clinics. A statement from a company executive disclosed that at the company’s Texas centers alone, there were “approximately 30,000 Mexican nationals donating and supplying over 600,000 liters of plasma [a year].” He describes Mexican donors as “loyal and selfless in their commitment to donating plasma.”

According to a filing by Grifols and CSL, the 24 border centers run by Grifols alone account for an “annual economic impact of well over $150 million” and represent approximately 1,000 jobs.

The trade organization for the pharmaceutical companies, the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association, has similarly reframed its arguments on the issue. In a 2019 statement, the association urged reporters not to attach any significance to “donation centers that happen to fall within areas states define as border zones.” It said then that it had no estimate of how much blood was being bought at the border or whether the amount was disproportionate when compared to the rest of the country.

But a recent court filing by the association said there are 52 plasma centers in the border zone, and “the average center along the border collects higher than average (31% more) plasma than the average center nationwide.”

Some of those donation centers were set up just steps away from the U.S.-Mexico border. Their location, court papers make clear, was part of a strategic effort to bring in Mexican donors: A memorandum written by the companies’ lawyers acknowledged that the centers were located to “facilitate” donations made by Mexican nationals and that Grifols and CSL “have also spent ‘several million dollars in the last several years’ on advertising to encourage Mexican citizens to donate plasma in exchange for payment at the centers located along the border.”

The memorandum did not specify if the ads were published in Mexico, but advertising for paid plasma donations is illegal in Mexico.

Short Term Visas

(U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, Donna Burton)

The Mexican nationals selling their blood previously entered the U.S. on what are known as B-1 or B-2 visas, documents that allow visitors to shop, do business or visit tourist sites. U.S. Customs and Border Protection had long viewed the practice of selling blood as a “gray area,” with some officials allowing short-term visitors to go to the centers while others did not. In 2021, about a year and a half after we published our 2019 story, the Border Patrol issued internal guidance that barred short-term visa holders from selling blood.

CSL and Grifols challenged that action, asserting that for 30 years, CBP had “largely allowed B-1/B-2 visa holders from Mexico to enter this country for the purpose of donating their plasma at collection centers that provide a payment to donors.” The CPB disagreed. Matthew Davies, a supervisory border security officer, told the court that selling plasma for compensation had never been a permissible activity.

On June 14, 2021, CBP sent out “clarifying guidance” that selling plasma on a visitor visa was not allowed. The announcement created chaos at the border centers. Two days later, Grifols wrote — and later deleted — a post on its Spanish-language Facebook page that said, “We are replying to the hundreds of messages asking when people with a visa can come back to donate. For the moment, the response is, you can’t.” An angry reply stated “Now, we’re no longer heroes who are saving lives. They just used us.”

Since then, donations at border centers have dropped dramatically. The pharmaceutical companies told the court that a survey of 12 centers in Texas found a 20 percent to 90 percent decline. “One particularly large center, which normally collects 5000+ donations per week, has decreased to a level closer to 200,” said the plasma association president, Amy Efantis.

Some previous donors interviewed by ProPublica said they would welcome a court ruling that set clear rules for people crossing the border to sell their blood. Genesis, a 23-year-old student from Ciudad Juárez, said she had worried about losing her visa when she entered the United States for her regular visits to the border clinics.

A current manager of a plasma collection center at the border, who asked not to be named because of the ongoing court case, said that he had to lay off about two-thirds of his employees and cut the center’s hours. “It would be good if they allowed [Mexicans] to donate again,” he said. “People are depending on this, on both sides.”

Stefanie Dodt is an investigative reporter and filmmaker.

This story was co-published by ProPublica and ARD German TV.

Firstly, please replace the term “blood” with “plasma”. There is a major difference.

Secondly, I’m not the least bit surprised that these parasite companies are in the mix. I’ve dealt with them in the past.

Yes! It is illegal to sell one’s whole blood in the USA, as opposed to being compensated for providing plasma. I have been under the impression that the collection centers rely on street people to provide their plasma, which was then used as a component of premium shampoos and the like. After all, would any able-bodied person have their blood drawn, wait around for the plasma to be centrifuged out and then receive a transfusion of the remainder only to be paid what seems to amount to chump change for the time spent and the discomfort endured?

I suppose there is no special level at which an imperial society acknowledges that it scalps its constituents.

Here’s to a day when the pretty pic of Al Hamilton is not worth a person’s blood or a person’s hours and people know it.

“But the Food and Drug Administration doesn’t require comparable donor checkups and allows people visiting American clinics to sell their blood twice a week, or up to 104 times a year.”

And the consequences of such lunacy can be devastating!

The contaminated blood scandal (UK):

“In the 1970s and 1980s 4,689 people with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders were infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses through the use of contaminated clotting factors. Some of those unintentionally infected their partners, often because they were unaware of their own infection. Since then more than 3,000 people have died and of the 1,243 people infected with HIV less than 250 are still alive.

Many people who did not have a bleeding disorder were infected with hepatitis C as a result of blood transfusions during that period. A large number were unaware of their infection for many years before diagnosis. It is not known how many were infected. ”

Source: The Haemophilia Society