Arbitrary borders, miserly aid and cruel policies ensure that those most victimized by conflict will remain adrift, writes Nick Turse.

Some of the people in Roe, 80 km from Bunia, Djugu, in the DRC, Feb. 22. Between 65,000 and 70,000 people live here, under the protection of the UN mission. (UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe)

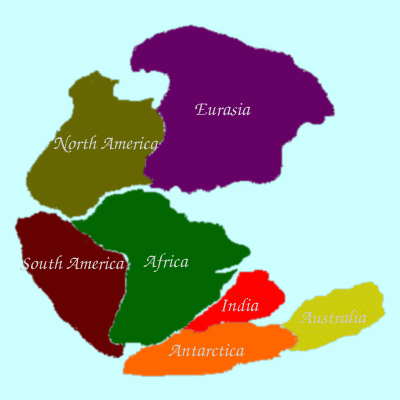

We live on a planet in motion, a world of collision and drift. This was once an Earth of super-continents — Gondwana, Rodinia, Pangea. The eastern seaboard of the United States sidled up against West Africa, while Antarctica cozied up to the opposite side of the African continent.

We live on a planet in motion, a world of collision and drift. This was once an Earth of super-continents — Gondwana, Rodinia, Pangea. The eastern seaboard of the United States sidled up against West Africa, while Antarctica cozied up to the opposite side of the African continent.

But nothing in this world lasts and the tectonic plates covering the planet are always in motion. Suddenly — over the course of hundreds of millions of years — supercontinents cease to be super, breaking into smaller land masses that drift off to the far corners of the world.

More recently, those itinerant continents were carved up by human beings into countries. A couple — China and India — are now home to more than a billion people each. But even modest-sized nations can be massive in their own right.

Spain and Canada, neighbors in Pangea hundreds of millions of years ago, now have populations of almost 47 million and nearly 38 million, respectively, making them the 30th and 39th most populous countries on this planet. But together, they’re no larger than a nation-less nation, a state of the stateless that exists only as a state of mind. I’m talking about the victims of conflict now adrift on the margins of our world.

(Markko, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The number of people forcibly displaced by war, persecution, general violence, or human-rights violations last year swelled to a staggering 84 million, according to UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency. If they formed their own country, it would be the 17th largest in the world, slightly bigger than Iran or Germany. Add in those driven across borders by economic desperation and the number balloons past one billion, placing it among the three largest nations on Earth.

This “nation” of the dispossessed is only expected to grow, according to a new report by the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), an aid organization focused on displacement. Their forecast, which covers 26 high-risk countries, predicts that the number of displaced people will increase by almost three million this year and nearly 4 million in 2023. This means that, in the decade between 2014 and 2023, the displaced population on this planet will have almost doubled, growing by more than 35 million people. And that doesn’t even count most of the 7 million-plus likely to be displaced by Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine.

“It is extremely worrying to see such a rapidly increasing number of displaced persons in such a short time,” said Charlotte Slente, the secretary general of the Danish Refugee Council. “This is where the international community and diplomacy need to step up. Unfortunately, we see a decreasing number of peace agreements and a lack of international attention to countries where displacement is predicted to rise most.”

Homeless Survivors of Nameless Wars

UN peacekeepers in Uvira, South Kivu, DRC, Sept. 24, 2017. (MONUSCO, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The history of humanity is a story of populations in motion, people eternally impelled and compelled and propelled to travel from here to there. The luckiest have always shoved off of their own volition, in comfort and with happy hearts. Many others have been shoved along in chains or at the point of a bayonet; forced to flee as bombs were crashing down around them; or because soldiers in military trucks or motorcycle-riding jihadis, armed with Kalashnikovs, came roaring into their villages.

It’s hard to wrap your mind around the enormity of 84 million people on the run today. It means that the population of the forcibly displaced is now more than doublethe number of Europeans driven from their homes by the cataclysm of World War II; six times the number of those displaced by the traumatic partition of India and Pakistan in 1947; or 105 times the number of Vietnamese “boat people” who fled to Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand during the 20 years that followed the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Thought of another way, about one in every 95 people on this planet is involuntarily on the move. Add in those driven by economic imperatives and one of every 30 people on Earth is now a migrant.

As of last June, nearly 27 million people were refugees on what Bob Dylan once called the “unarmed road of flight” — with 68 percent of them hailing from five countries: Syria (6.8 million), Venezuela (4.1 million), Afghanistan (2.6 million), South Sudan (2.2 million), and Myanmar (1.1 million). Far more of the forcibly displaced are, however, homeless within their own lands — victims of conflicts that go largely unnoticed by the wider world.

Tents for people who has taken refugee next to UN base in Pibor, South Sudan, as result of conflicts in Jonglei state, March 6, 2020. (UN Photo/Isaac Billy)

In 2018, I watched as a postage-stamp-sized camp for displaced people in Ituri Province in the far east of the Democratic Republic of Congo mushroomed from hundreds of people to more than 10,000, spilling beyond its borders and necessitating the creation of another sprawling encampment across town. At the time, women, children, and men in Ituri were being butchered alive by militiamen armed with machetes. And the attacks have never fully abated. Three years later, the violence and displacement continues.

In the first 10 days of this month alone, militiamen carried out eight attacks in Ituri. On February 1st, a massacre at a displaced persons camp there killed 62 people, injured 47, and displaced 25,000, adding to the already astronomical numbers in Congo. Around 2.7 million Congolese were driven from their homes between January and November 2021, according to the United Nations, swelling the grand total of internally displaced people in that country to 5.6 million.

In 2020, as I traveled an ocher dirt road in Burkina Faso, a tiny landlocked nation in West Africa, I watched an unfolding humanitarian catastrophe. Families were streaming down that road from Barsalogho about 100 miles north of the capital, Ouagadougou, toward Kaya, a market town whose population had almost doubled that year. They were victims of a war without a name, a lethal contest between Islamist terrorists who massacre without compunction and government forces that have killed more civilians than militants.

And the suffering there persists as that conflict continues to force people from their homes. The number of internally displaced Burkinabe jumped 50 percent last year to more than 1.5 million, while another 19,200 people fled to neighboring countries, a 50 percent increase over 2020. This year, according to the Danish Refugee Council, an additional 400,000 Burkinabe will likely be displaced. And that’s only part of a wider regional crisis that has engulfed neighboring Mali and Niger where another one million people have been rendered homeless.

March 2, 2011: At the Tunisia-Libya border, thousands of people anxious to leave Libya gathered in a no-man’s land on the Libyan side. As the crowd surged towards the border gate, several people were injured. (UN Photo/UNHCR/Alexis Duclos)

Across the continent, the civil war in Ethiopia that began in November 2020 has left it with one of the world’s largest internally displaced populations. At the end of that year, 2.1 million people had already been put to flight within the country. By the close of 2021, that number had doubled to 4.2 million. As in Congo, violence and displacement has left some of the unluckiest doubly victimized. Earlier this month, for example, Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia’s Barahle refugee camp were attacked by armed men who killed five of them, kidnapped several women, and sent more than 14,000 refugees fleeing to other towns.

Afghanistan has been the site of still another conflict-driven crisis. Since the U.S. invasion of their country in 2001, almost 6 million Afghans have been either internally displaced or become refugees, according to Brown University’s Costs of War Project. Similarly, more than 10 years after the start of the civil war in Syria, half that country’s population remains trapped in limbo with about 6.6 million of them refugees abroad and 6.7 million displaced within their own country.

The February 2021 military takeover in Myanmar similarly spawned a mammoth displacement crisis with armed clashes, including airstrikes and shelling, accelerating the suffering. There are now at least 980,000 refugees and asylum-seekers from Myanmar in neighboring countries and around 812,000 internally displaced peoplethere, including 442,000 forced from their homes since the coup.

Continental Divide

Refugee camp in Hajjah province, Al-Mazraq, Yemen Oct. 9, 2009. (Paul Stephens, IRIN, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In 2014, about 9 million of the world’s displaced lived in low-income countries. Today, that number stands at an estimated 36 million and is forecast, by the Danish Refugee Council, to increase to 40 million by the end of 2023. The displacement crisis “disproportionally affects poorer countries and areas that already have enough on their plate,” said the Council’s Charlotte Slente. “We see that humanitarian funding is inadequate in a number of countries where displacement is taking place.”

The DRC’s forecast, based on a sophisticated model utilizing more than 120 indicators related to conflict, as well as to governance and environmental, demographic, and economic factors, suggests that Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, South Sudan and Sudan will all experience significant displacement in 2022 while Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Somalia are likely to see substantial increases in 2023. All told, the Council predicts that the number of people in sub-Saharan Africa driven from their homes will jump by more than five million by the end of next year.

In 2020, as I traveled down a road in a comfortable SUV with a heavily armed police escort toward the conflict zone in Burkina Faso, I watched families who had hitched up their donkeys and piled everything they could — kindling, sleeping mats, cooking pots — into sun-bleached carts heading the other way. If we were still living on the super-continent of Pangea, they could have bypassed the way station in Kaya and headed west through Mali and Guinea, ending up in Miami, Florida. But today that city of “cutting-edge art galleries, top-notch restaurants and funky but chic boutiques” where the median home price is $471,000 and a country where 80 percent of the population lives on less than $3 per day are a world apart or, rather, separated by 250 million years and 5,200 miles.

We live in a world where continental drift has left so many displaced Afghans, Burkinabe, Congolese, and others bottled up inside their own borders or in neighboring nations that are ill-equipped to bear the burden. The tyranny of the oceans that separate those displaced by conflict from safety has been intensified by callous governments, sealed borders, and heartless policies that curtail and criminalize humanity’s most ancient response to danger: flight.

The very least the world’s comfortable classes could do is throw money at the problem. The U.S. government — responsible for up to 60 million displaced people in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, the Philippines, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen due to its war on terror — bears a special responsibility, but hasn’t stepped up. “Funding constraints continue to hamper [the] humanitarian response to displacement,” reads the Danish Refugee Council’s 2022 Global Displacement report. “Looking at the current forecasts for 2022 and 2023, crises where humanitarian funding and attention from the international community is lacking, displacement is forecast to increase significantly.”

In the countries where humanitarian response plans were more than 50 percent funded in 2021, displacement is predicted to increase by an average of 59,000 people. In those where funding was less than 50 percent, it’s projected to jump by 160,000 people, on average. “The international community needs to step up with extra support to the countries that are most affected by displacement,” said the DRC’s Slente.

If only.

One day, our itinerant continents will slam back together with, according to some forecasts, North America crashing into Africa, old neighbors rejoined after so much time apart. It will, unfortunately, be 300 million years too late for those now within the nationless nation, those rendered homeless by war, violence, and persecution. Our arbitrary borders, miserly aid, and cruel policies ensure that those most victimized by conflict will remain adrift, wandering the planet in search of safety, discarded by the rest of us as marginal people on the margins of an unforgiving world.

Nick Turse is the managing editor of TomDispatch and a fellow at the Type Media Center. He is the author most recently of Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead: War and Survival in South Sudan and of the bestselling Kill Anything That Moves.

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.