The Nobel awarders will present the peace prize on Friday with full confidence they will once again get away with the betrayal of the antimilitarist purpose at the heart of Alfred Nobel’s testament in 1895, writes Fredrik S. Heffermehl.

Bust of Alfred Nobel in front of the Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. (Brage Aronsen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Fredrik S. Heffermehl

in Oslo

Special to Consortium News

The 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, which will be presented on Friday, honored press freedom and, no surprise, was welcomed by the world press.

The 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, which will be presented on Friday, honored press freedom and, no surprise, was welcomed by the world press.

As I listened to the announcement, on Oct. 8, an old story from the Cold War kept coming back to me. A Soviet official had been traveling in the U.S. for a couple of weeks. As he left, he remarked to his hosts, in puzzled bewilderment: “How can it be that you have such perfect control, even with a completely free press?”

He was right. Society makes one huge exception from democracy and press freedom: national security. The military-industrial complex is in control and thoroughly disciplined media see it as a sacred duty to keep their own nation strong and united behind the flag and the forces. Nations are governed by fear that any doubt or deviation from military orthodoxy would harm national security.

As a result, in 2021 the Nobel awarders could praise two persecuted journalists, Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Russian Dmitry Muratov, with full confidence that it would once again get away with its betrayal of the antimilitarist purpose at the heart of Alfred Nobel’s testament in 1895.

For 120 years the awarders have been permitted to misuse the prize for their own ideas. Thus, the Nobel Peace Prize illustrates a black hole in press freedom. The same fate befell the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The two had the same purpose, but were immediately taken over by the military forces the original donors hoped to eliminate.

Replacing the War System

To understand the meaning of these initial donations properly, we need to examine the thinking of the period and of the personal ideas of the two donors.

The idea of replacing the war system with a co-operative world order based on international law was close to success in the aftermath of the anti-war bestseller of Austrian Bertha von Suttner, Lay Down your Arms (1889).

She inspired a great political movement and induced an enthusiastic Alfred Nobel in 1901 to establish his prize for “abolition or reduction of standing armies.” Ten years later Andrew Carnegie one-upped Nobel by selling the Steel Trust in 1911 and investing his fortune in peace.

Support CN’s Winter Fund Drive!

Both donations signaled a wish to turn the path of history: end war by liberating countries from weapons and warriors. Nobel´s intention is evidenced by a letter he wrote from Paris, asking a cousin in Stockholm to buy the newspaper Aftonbladet because “he wished to own a liberal paper that could put an end to war, and other relics from medieval times.”

Similarly, Carnegie expressed in a founding document that the main task of the trustees was to end war. Only when that goal had been achieved could the trustees go on to attack the lesser evils.

But the military establishment prevailed in the battle between these two fundamentally different ideas. The attempt to realize a world peace order failed in the First Hague Peace Conference in 1899. A contemporary report says:

“Those who believed in the path of trust and co-operation stood against those who warmly defended the old belief that nothing but weapons can resolve international conflicts.”

In our time the “old belief” has come pretty close to the only belief. Even the trustees of Nobel and Carnegie do not stand up for the global demilitarization that they are supposed to serve.

2021 winner Ressa condemns Julian Assange and says purpose of journalism is to support national security.

Nobel’s Vision Dashed

Nobel left the appointment of five trustees for the “prize for the champions of peace” to the Parliament of Norway. He must have liked the fact that Norway, as a junior partner in a union with Sweden, did not have its own foreign policy. Moreover, Norway had been a pioneer in supporting a main peace organization of the author von Suttner.

In my newest book on the prize, Fame or Shame (in Norwegian, the English translation is seeking a publisher), I have found out why the choice of Norway became a fatal mistake: in the exact year that Nobel made his will, 1895, Norwegian politicians shifted from supporting world peace to building military strength for a potentially violent exit from the union with Sweden.

The speakers of the Norwegian Parliament did not hesitate to discard Nobel’s main tool for peace, global disarmament, and make it a prize for “peace” in general, i.e., embezzle the prize and use it for whatever they liked.

The prize Nobel intended never happened, the Norwegian awarders chose never to conduct the necessary professional interpretation of Nobel’s intention. The committee also never — except in 1905 and 1910 — spoke up for the vision of peace that Nobel wished it to support.

Norwegian Nobel Committee meeting in 1897. (Ernest Rude, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Total secrecy applies, no member may reveal anything from the award committee’s internal discussions, but the preparatory reports the committee based its discussions on are available and show that their deliberations never contained an iota of interest in Nobel’s own vision of peace. Instead, there are several expressions of contempt for the peace advocates and ideas Nobel wished the committee to back.

In the award ceremonies, the laureates often supported the ideas of Nobel much better than the awarders were ever willing to. But the media have offered awe and praise and shown little will to stand up for the pacifist ideas and people who were entitled to win under the law.

A Year in the Archives

To show who they were, what the prize should have been, and the world we could have had, I spent a year in the well-guarded archives of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. Here I dug out the candidates who were best qualified to win instead of those preferred by the committee, a comprehensive alternative history of how to create a peaceful, non-violent world order.

This is the reform the world, with all the other threats facing it, desperately needs, and the U.S. more than most. No population in today’s world would seem to need it more than the poor and disadvantaged of the U.S. itself.

The book relates 114 heartbreaking stories of people who were cheated of the prizes Nobel wished to give them. It is a hitherto unwritten history of suppressed ideas and unsung heroes in a thankless struggle to liberate us all from weapons, warriors and war.

The book relates 114 heartbreaking stories of people who were cheated of the prizes Nobel wished to give them. It is a hitherto unwritten history of suppressed ideas and unsung heroes in a thankless struggle to liberate us all from weapons, warriors and war.

Nothing surprised me more than seeing how much the U.S. is a leader in the field of peace. With her 22 prizes, the U.S. is recipient of twice as many prizes as the three next biggest winners. Even if, following Nobel’s actual intention, I flunk 17 of the awarded prizes as cultivating the wrong, militarist USA, I conclude that the U.S. was cheated of 39 true Nobel prizes and should have had 44 recipients – still twice as many as the next countries.

As this research progressed, I got more and more interested in what the Nobel prize history has to tell us about our democracies and issues of press freedom – with the giant elephant in the room being the lack of alternative views on the military.

Taking Norway as an example, we opted for military power in 1949. Our accession to NATO resulted in a broad agreement never to question the steady development of military capacity and our allegiance to the U.S. and the alliance.

For more than 70 years politicians and just about everyone else have been in keen competition to be the most devoted and loyal NATO supporters. But it seems to be dawning on Norwegians that the time may have come to turn off the autopilot, not least after the conservative cabinet concluded a treaty with the U.S. to set up American bases on four airfields in Norway. The conservatives lost the national elections in early September.

Pleasing the US

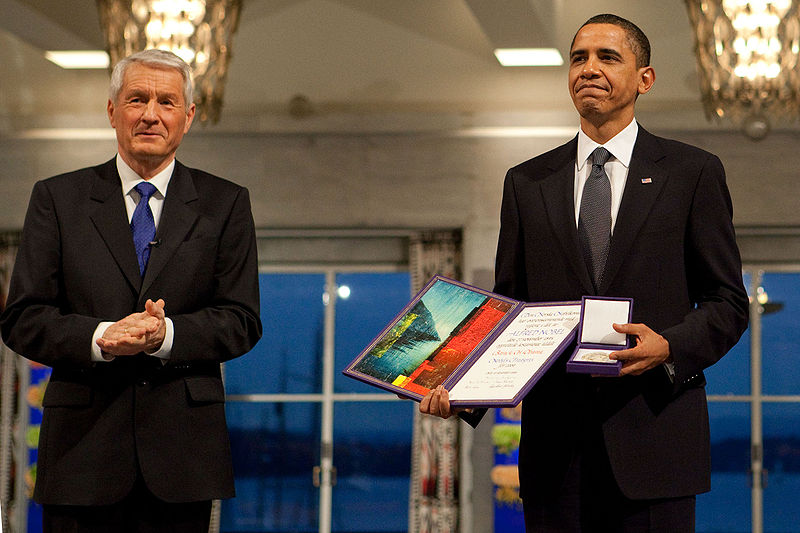

Dec. 10, 2009: President Barack Obama, at right, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize from Committee Chairman Thorbjorn Jagland in Oslo, Norway. (White House photo)

But again, the Norwegian Nobel Committee, with its 2021 prize, is showing perhaps the most solid criterion for its award policy: if possible, to please and never offend the United States.

This started with the 1906 prize for President Theodore Roosevelt, and continued with prizes for Woodrow Wilson, Frank Kellogg, George Marshall, Henry Kissinger, Jimmy Carter, Barack Obama and others — all very far from the grassroots peace and nonviolence protagonists Nobel had in mind. Another trend — excepting a handful of antinuclear winners — is conferring the prize in line with the politics of the U.S. and the West. Or to embarrass opponents of the West, as in the cases of Andrej Sakharov, Lech Walesa, Liu Xiaobo, or the 2021 prizes for Maria Ressa and Russia´s Dmitry Muratov.

In its 2021 announcement the committee stated that it wished “to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda.” But the committee missed a formidable opportunity to be fully loyal to Alfred Nobel and at the same time serve press freedom.

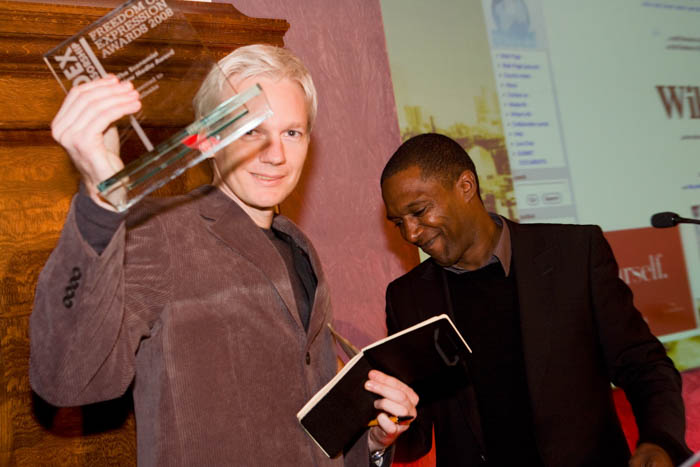

Assange and WikiLeaks won The Economist New Media Award at the 2008 Freedom of Expression Awards. (Index on Censorship)

One of the candidates nominated for 2021 had made a unique challenge to the forces Nobel wanted to fight. The most acute and deadly threat to press freedom in the world today is the U.S. campaign against Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, who deserves thanks from the world for making known war crimes committed by the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Russian press freedom is, after all, a local problem, but the U.S. attack on Assange will deter media around the world from speaking out critically about U.S. abuse of power and high crimes. So far, Assange has been deprived of health and liberty for 10 years. He is being held as a political prisoner, isolated in Belmarsh high-security prison in London, without charge and sentence, pending the judgment [also on Friday] in a U.S. appeal against a British court’s refusal to extradite him.

His courageous revelations have been honored with torture that has ruined his health. His life is at risk. A committee loyal to Nobel’s peace vision could have helped protect Assange from extradition and perpetual deprivation of liberty in the United States.

A great paradox is this: if the power-critical press freedom ostensibly praised by the 2021 Nobel award had worked – towards the committee itself and the powerful military-industrial sector – the Nobel Committee would not have succeeded with its betrayal of the core of Alfred Nobel’s peace vision over the past 120 years.

Fredrik S. Heffermehl, Oslo, is a lawyer and author. His latest book is Medaljens bakside (Fame or Shame).

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!

Donate securely with PayPal

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

I learned some significant history here and truly appreciate it. The sad knowledge of the Prize’s perversion is accompanied by my scorn for Ressi, and together the true facts being known about both her and the Prize make for a discordant harmony of ill repute.

Takk Hr Heffermehl.

Jeg skal kjøpe boken din i julegave til meg selv.

Frankly…I find the entire US society is despicable, repulsive, immoral, unethical – out to look after itself and only itself while pretending to bring ‘democracy’ to the world. As Biden stated “America is back” …just stay where you were, we did OK without you.

Thanks for writing this article. I will pick up your book and read it before the end of the year. Julian would have made the ideal Nobel peace prize winner if the goal was to support both the idea of peace and the idea of press freedom.

Maria Ressa’s insulting remarks about Julian Assange’s expose of US government-documented international crimes as non-journalism and lacking deference to US national security establish her credentials as a willing intellectual partner of US intelligence apparatus. Given the Nobel Prize Committee’s track record of subservience to US power, Maria Ressa truly deserves the Peace Prize according to the US empire’s concept of peace.

Julian Assange’s truthful revelations of US empire’s international crimes were a real service to humanity – and deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize according to Alfred Nobel’s idea of genuine peace.

Unfortunately imperial criminals own the world including the Nobel Prize Committee. Pesteng yawa gid.