Newly released files show the U.K. had a role in ushering in the brutal 21-year military dictatorship, reports John McEvoy.

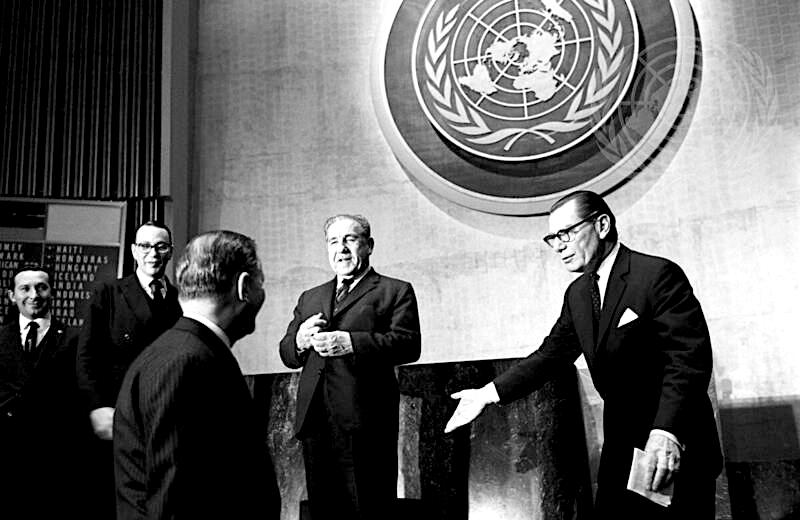

April 6, 1962: Brazilian President Joao Goulart, second from left, with UN Acting Secretary General U Thant. (UN, Marvin Bolotsky)

By John McEvoy

Declassified UK

On March 31, 1964, a military coup was launched against Brazilian President João Goulart. Brazil’s democracy was already fragile, and Goulart’s attempt at an ambitious program of land reform while extending the vote to Brazil’s illiterate population incensed the country’s political, military and business elite.

The coup culminated on April 1, 1964, and ushered in a 21-year military dictatorship. During this time, over 400 individuals were killed by the Brazilian military, and many more were “disappeared,” tortured or imprisoned.

Washington’s hand in the coup is well known. After Goulart acceded to the presidency in 1961, the CIA began pouring money into the country, covertly supporting street rallies and inciting anti-communist sentiment. Once the coup was underway, President Lyndon Johnson instructed his aides to “do everything that we need to do” to support it.

President John F. Kennedy, left, and Brazilian President João Goulart, right, during a review of troops on April 3, 1962. (U.S. Army, Wikimedia Commons)

The Information Research Department (IRD), a unit of the Foreign Office that acted as Britain’s secret propaganda arm during the Cold War, was also active in Brazil. Though the U.S. clearly played a more prominent role, recently declassified files reveal Britain’s hidden hand in the coup through its support of key agitators.

‘Plenty of Use for IRD Material’

In 1962, a Brazilian engineer named Glycon de Paiva helped to found the Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos Sociais (IPES). While IPES posed as an educational institute, its real aim was “organizing opposition to Goulart and maintaining dossiers on anyone de Paiva considered an enemy.”

IPES was closely connected to Brazil’s military, political and business elite. With General Golbery do Couto e Silva as its chief of staff, the organisation compiled 400,000 files on left-wing “enemies” of Brazil, cultivated an army of informants and propagandised against the government.

After the coup, IPES grew into Brazil’s National Intelligence Service (SNI), which “served as the backbone of the military regime’s system of control and repression.”

Column of M41 Walker Bulldog tanks along the streets of Rio de Janeiro in April 1968. (Correio da Manhã, Wikimedia Commons)

Newly declassified files detail British support for IPES. On Feb. 6, 1962, IRD field officer Robert Evans described how “one of the most significant developments affecting my activities has been the formation of IPES.”

A week later, IRD official Geoffrey McWilliam received a letter about “Businessmen’s Anti-Communist Organisations” in Brazil. The sender remains classified, and appears to be the British security services.

The letter noted that “since IPES’s main task during the coming months will be to ensure that the Congress does not fall into Communist hands in the October elections, they will presumably have plenty of use for IRD material.”

It was noted with concern, however, that IPES was being too brazen about foreign support. The letter continued that

“IPES, in its desire to mobilise foreign firms, is at present being rather brash (publishing sets of their manifesto in English, with sign-on-the-dotted-line membership cards, etc). We (and the Americans) are trying to convince them to be more discreet about it, and to discourage British firms from making their support too overt.”

Shortly after, British firms in Brazil created a foundation to more discreetly provide funds to IPES — a scheme which had “the approval of HM Ambassador and FO [Foreign Office] departments.”

The Foreign Office also agreed to assist IPES directly. Senior IRD official Rosemary Allott permitted IPES to receive “our material,” but direct financing of its publishing operations was not advised.

The Foreign & Commonwealth Office main building in London. (FCO, Flickr)

Eleven days before the coup, Robert Evans noted that “I keep in close touch with the Rio branch of IPES over Portuguese language editions of IRD literature, and for getting material to the armed forces.”

He added that he hoped to meet an army general “who seems to have developed a singularly successful method for dealing with Communist front organisation meetings.”

After the coup, the British embassy reviewed IRD’s clandestine operations in Brazil. “Before the Revolution our main IRD effort was not made with the knowledge and approval of the authorities,” wrote British ambassador Leslie Fry.

In an apparent reference to IPES, Fry continued that

“some of the IRD contacts turned out to be the summits of quite large icebergs, with responsible leadership. […] One or two leading personalities have been going around talking about his [IRD field officer Evans] contribution to the defeat of Communism in Brazil. Quite true, but not the sort of thing we want said.”

Producing Forged Documents

During the early 1960s, Evans also agreed to take “limited action as and when opportunity offers” to counter left-wing activity in Brazil’s student field.

One such action involved accessing “strategic points where students congregate” during the night, and sticking up anti-communist propaganda “in lecture halls, class-rooms, lavatories, canteens etc.” It was an operation which “could, of course, be applied equally well throughout the continent.”

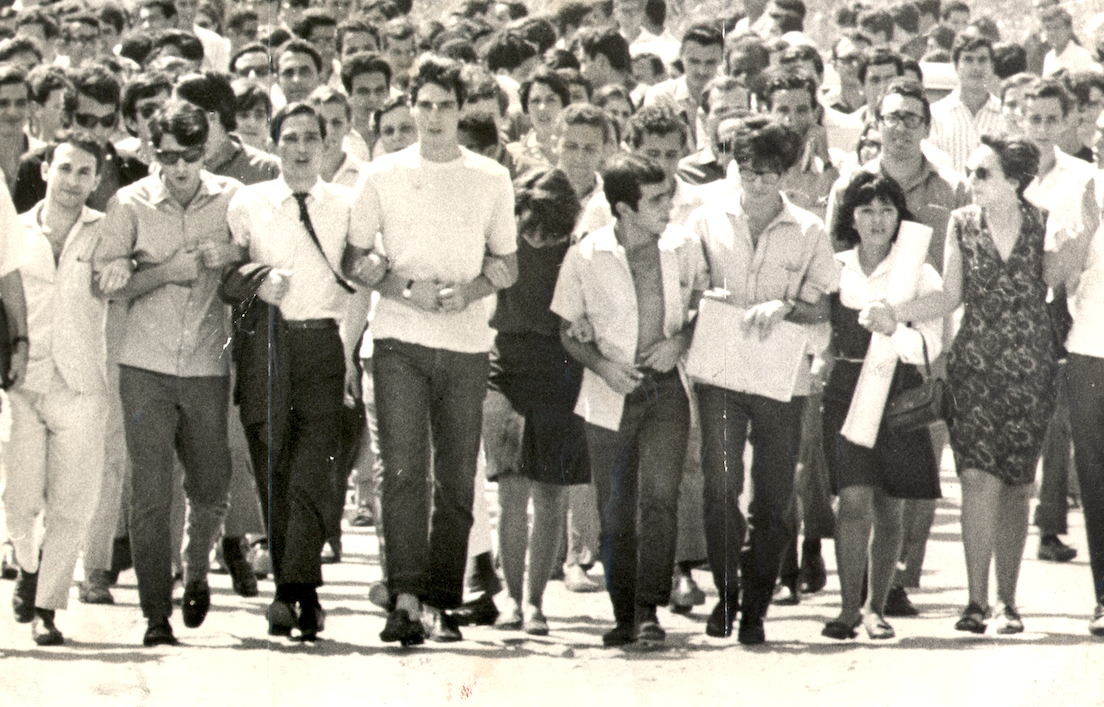

Students in Brazil protesting against the military dictatorship in 1966. (Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons)

According to documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, the IRD also collaborated with the U.S. by producing forged documents.

On March 12, 1964, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk complained to Brazilian officials about a Congress for Solidarity with Cuba “to be held in Rio with participants from all over the world.”

Three days later, IRD official J.L. Welser wrote to the U.S. embassy in London about producing “some kind of black leaflet” to disrupt the event. “Black” propaganda signified falsifying documents — a risky operation which IRD planners rarely engaged in.

“We have tried to do this and have not found it very easy,” Welser wrote to his U.S. contact.

“However, we have done a leaflet which I attach with this letter and which you may care to look at. […] I am sorry to have been so slow about this but it is not easy to write a thing of this kind.”

Shortly after, Welser was congratulated “on an excellent job.”

The IRD also assisted União Cívica Feminina (UCF), a Catholic women’s movement which mobilised mass anti-government street rallies in the weeks before the coup.

In June 1964, Evans boasted that the UCF had been “fed with a steady diet of IRD material for over a year,” and “played a leading role in recent events.” British embassy official J. MacKinnon agreed, noting how “women played a vital role in the April 1 revolution.”

After the Coup

Jan. 31, 1967: Brazilian President da Costa e Silva, at center, facing camera, is welcomed to UN headquarters in New York by the UN’s chief of protocol. (UN, Yutaka Nagata)

The coup was welcomed by British planners. In July 1964, Fry observed that “the immediate IRD objective is achieved.”

The next year, British officials discussed welcoming coup instigator General Costa e Silva to Britain. “The honours which we show the General”, wrote Fry in December 1965, “may well prove as important a contribution towards the sale of British equipment to Brazil as the merits of that equipment itself,” referring to arms sales.

After becoming Brazilian president in 1967, Costa e Silva signed Institutional Act No. 5, which permitted the closure of Congress, removed habeas corpus, outlawed political meetings, and provided a carte blanche for torture. These measures were received “with satisfaction by those concerned with industry and commerce,” noted IRD field officer R.A. Wellington.

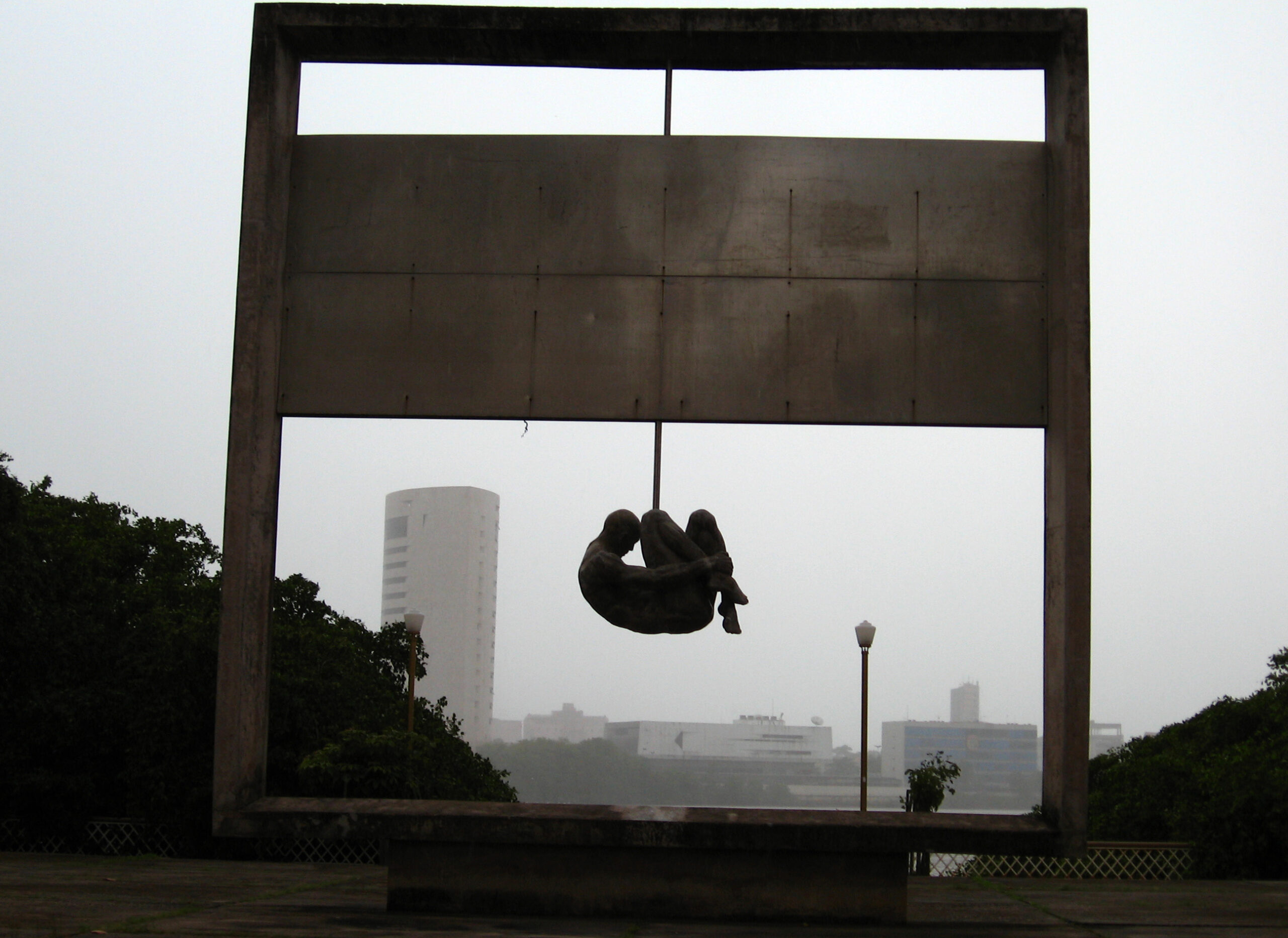

Monument to the victims of torture in Recife, Brazil. (marcusrg, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Despite massive human rights abuses, the IRD continued “to help Brazil discreetly in the field of counter-subversion” during the 1970s. Its material covered “anti-communist themes […], Black Power, the student situation, and Britain’s position in regard to Gibraltar.”

At this time, Evans was producing literature diminishing the impact of foreign intervention in the coup of 1964.

Brazilian journalist Geraldo Cantarino, who in 2011 published a detailed book on IRD operations in Brazil, commented on the latest revelations:

“This work reinforces that the IRD was covertly active in Brazil for many years, joining forces with the U.S. anti-communist crusade and with the anti-communist propaganda engineered by Brazilian institutions.”

He added: “It is now possible to restate that this combined effort contributed to the destabilisation of President Goulart’s government, paving the way for a military regime that changed the course of Brazil’s recent history.”

John McEvoy is an independent journalist who has written for International History Review, The Canary, Tribune Magazine, Jacobin and Brasil Wire.

This article is from Declassified UK.

I can remember I had just left school . I read a lot and got a subscription to Reader’s Digest. In those days I, and I think most people, knew less about how publications tried to manipulate public opinion. One issue ‘explained’ how the military had saved Brazil from communist plots. I took it at face value.

As a Brazilian who was born in 1980, I appreciate articles like this. It’s important to remember that Latim America during the 60’s and 70’s was a Wild West, a laboratory for the US and UK intelligence services. A lot of the strategies they have used more recently to destabilize the Middle East, push for Brexit and distort their own democracies, was likely perfected during all the dictatorships they supported all those years ago.

At the time, naturally, this brutally anti-democratic course of action was widely debated in the UK media; there were fractious debates in the House of Commons; MPs were inundated with letters from constituents outraged at learning how their government was aiding the end of democracy in Brazil… oh, and then I woke up. It’s time we understood that pretty much every UK government is committed to the cause of ending democracy wherever it tries to emerge, including in the UK.