By pulling the realities of war out of its carefully crafted public context, the WikiLeaks founder became a danger to the country’s political status quo, writes Robert Koehler.

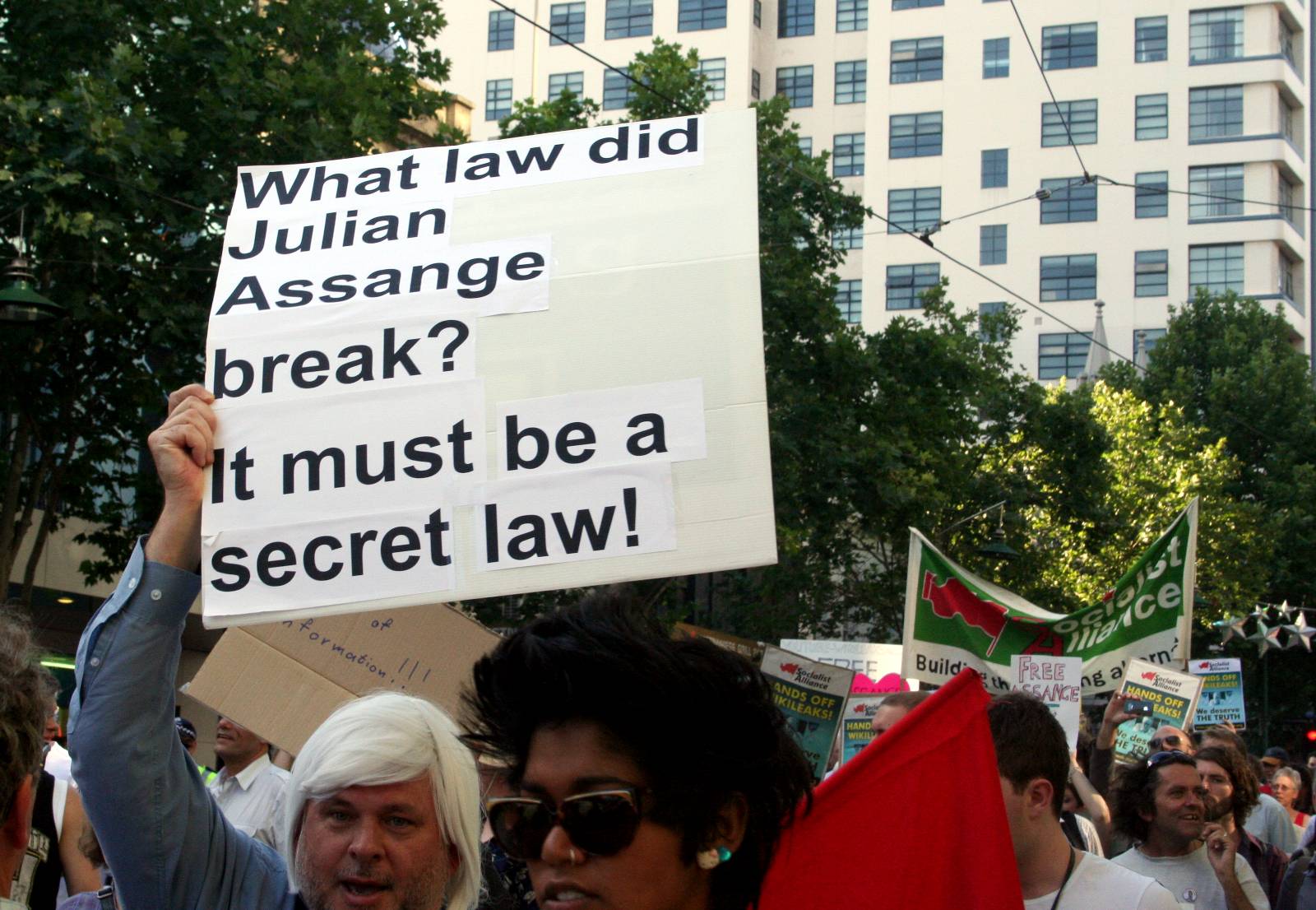

Assange supporters rally in Melbourne, Australia, Dec. 14, 2010. (Flickr/Takver)

By Robert C. Koehler

Common Dreams

The Pentagon’s offer of “condolence money” to the relatives of the 10 people (seven of them children) who were killed in the final U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan— originally declared righteous and necessary — bears a troubling connection to the government’s ongoing efforts to get its hands on WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and punish him for exposing the inconvenient truth of war.

The Pentagon’s offer of “condolence money” to the relatives of the 10 people (seven of them children) who were killed in the final U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan— originally declared righteous and necessary — bears a troubling connection to the government’s ongoing efforts to get its hands on WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and punish him for exposing the inconvenient truth of war.

You know, the “classified” stuff — like Apache helicopter crewmen laughing after they killed a bunch of men on a street in Baghdad in 2007 (“Oh yeah, look at those dead bastards”) and then smirked some more after killing the ones who started picking up the bodies, in the process also injuring several children who were in the van they just blasted. This is not stuff the American public needs to know about!

You know, the “classified” stuff — like Apache helicopter crewmen laughing after they killed a bunch of men on a street in Baghdad in 2007 (“Oh yeah, look at those dead bastards”) and then smirked some more after killing the ones who started picking up the bodies, in the process also injuring several children who were in the van they just blasted. This is not stuff the American public needs to know about!

At the time of the release of that particular video, in 2010, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates decried the fact that the public was seeing a fragment of the war on terror “out of context.”And, indeed, he was right. As I later wrote:

“The Department of Defense is supposed to have total control over context; on the home front, war is 100 percent public relations. The public’s role is to be spectators, consumers of orchestrated news; they can watch smart bombs dropped from on high and be told that this is protecting them from terrorism and spreading democracy. That’s context.”

Assange’s crime was collaborating with whistleblowers to expose hidden data and disrupt that context. Over the course of a decade, WikiLeaks published some 10 million secret documents, more than the rest of the world’s media combined, according to a Progressive International video.

This is the organization that has launched the Belmarsh Tribunal, which is demanding that Assange be released from British prison and not be extradited to the United States. The Tribunal, modeled after the 1966 tribunal organized by Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre to hold the U.S. accountable for its actions in Vietnam, has put the country on trial for its 21st century war crimes.

Threatening the Abstraction of War

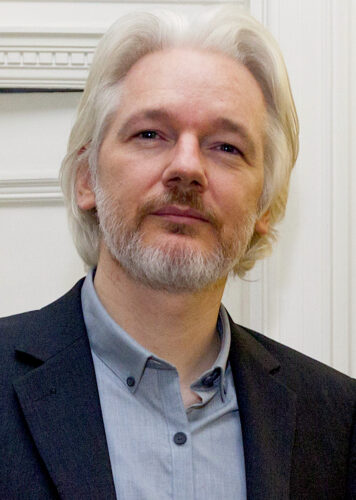

Julian Assange in 2014. (David G Silvers, Wikimedia Commons)

The government’s desperation to extradite, try and essentially get rid of Assange is profoundly understandable. He is a threat to war itself — that is to say, to the abstraction of war, i.e., “national defense,” which claims a trillion dollars a year in unquestioned (and ever-increasing) funding and sits in the public consciousness as just the way things are.

By penetrating the realities of war and pulling it out of its carefully orchestrated public context, by publicizing its raw horrors, he became a danger to the country’s political status quo.

So much so, in fact, that: “In 2017,” Yahoo! News reported a month ago, “as Julian Assange began his fifth year holed up in Ecuador’s embassy in London, the CIA plotted to kidnap the WikiLeaks founder, spurring heated debate among Trump administration officials over the legality and practicality of such an operation.

“Some senior officials inside the CIA and the Trump administration even discussed killing Assange, going so far as to request ‘sketches’ or ‘options’ for how to assassinate him. Discussions over kidnapping or killing Assange occurred ‘at the highest levels’ of the Trump administration, said a former senior counterintelligence official. ‘There seemed to be no boundaries.'”

The disaster known as the Vietnam War that ended in U.S. disgrace —which had to end because the country’s own troops had turned against it in huge numbers — led to something called the “Vietnam Syndrome,”a public disgust for war itself. What an inconvenience for the government, which was still engaged in its Cold War with the communists but could only wage proxy wars, e.g., in Nicaragua, where the contras had to do the dirty work.

U.S. soldiers torching grass huts in My Tho, Vietnam., April 5, 1968. (Army Specialist Fourth Class Dennis Kurpius/Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, in 1991, as George H.W. Bush launched Gulf War One in Iraq, he declared: “By God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all.”

The U.S.A. was finally free to militarize its propaganda again, that is to say, to spread democracy around the globe with the help of bombs and bullets. Since the Soviet Union had collapsed and the Cold War had ended, a new enemy had to be found, but that was no problem. A decade later, Bush Jr. launched the War on Terror and the endless wars of the 21st century began.

And they were good.

Well, they were good as long as the Department of Defense had control over their context. Assange, by defying all restrictions on the truth and exposing the raw realities of these wars — the lies, the hell — could bring the statistics of war to life, e.g.:

“At least 801,000 people have been killed by direct war violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Pakistan,”according to Brown University’s Costs of War Project. “The number of people who have been wounded or have fallen ill as a result of the conflicts is far higher, as is the number of civilians who have died indirectly as a result of the destruction of hospitals and infrastructure and environmental contamination, among other war-related problems.”

And:

“Millions of people living in the war zones have also been displaced by war. The U.S. post-9/11 wars have forcibly displaced at least 38 million people in and from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria. This number exceeds the total displaced by every war since 1900, except World War II.”

The U.S. government has apologized for 10 of those deaths, and only —only! — because the incident was investigated and came to public attention.

Robert Koehler is an award-winning, Chicago-based journalist, nationally syndicated writer and author of Courage Grows Strong at the Wound (2016). Contact him or visit his website at commonwonders.com.

This article is from Common Dreams.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our

Fall Fund Drive!