Behind the rhetoric about the Indo-Pacific and open seas is the U.S. play in Southeast Asia, writes Prabir Purkayastha.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a 2017 meeting of the leaders of BRICS — or Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. (Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Prabir Purkayastha

Globetrotter

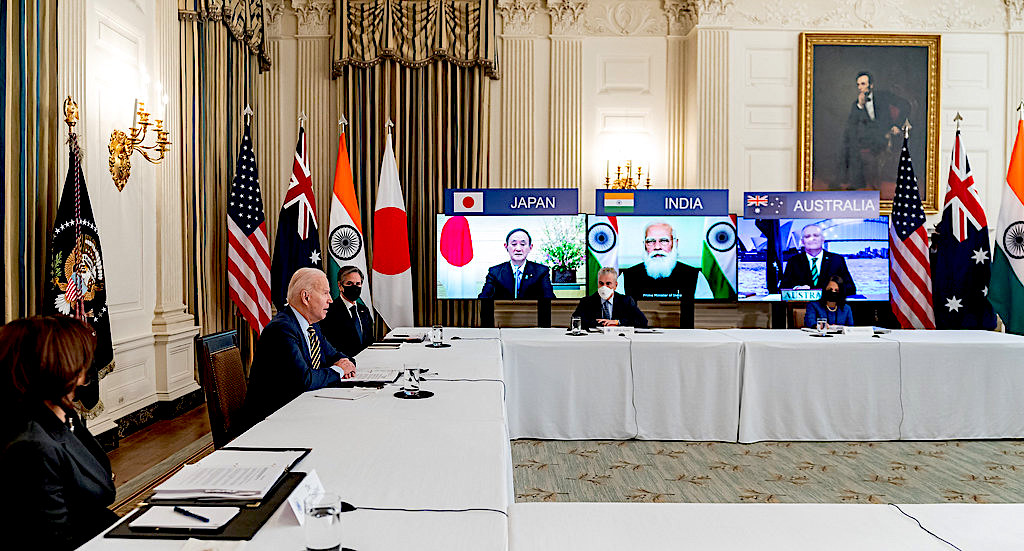

The Quadrilateral group’s leaders’ meeting in the White House on Sept. 24 appears to have shifted focus away from its original framing as a security dialogue among four countries: the United States, India, Japan and Australia.

The Quadrilateral group’s leaders’ meeting in the White House on Sept. 24 appears to have shifted focus away from its original framing as a security dialogue among four countries: the United States, India, Japan and Australia.

Instead, the United States seems to be moving much closer to Australia as a strategic partner and providing it with nuclear-powered submarines.

Supplying Australia with U.S. nuclear submarines that use bomb-grade uranium can violate the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) protocols. Considering that the United States wants Iran not to enrich uranium beyond 3.67 percent, this is blowing a big hole in its so-called rule-based international order — unless we all agree that the rule-based international order is essentially the United States and its allies making up all the rules.

Supplying Australia with U.S. nuclear submarines that use bomb-grade uranium can violate the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) protocols. Considering that the United States wants Iran not to enrich uranium beyond 3.67 percent, this is blowing a big hole in its so-called rule-based international order — unless we all agree that the rule-based international order is essentially the United States and its allies making up all the rules.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had initiated the idea of the Quad in 2007 as a security dialogue. In the March 12 statement issued after the first formal meeting of the Quad countries, “security” was used in the sense of strategic security.

Before the recent meeting of the Quad, both the United States and the Indian sides denied that it was a military alliance, even though the Quad countries conduct joint naval exercises — the Malabar exercises — and have signed various military agreements. The Sept. 24 Quad joint statement focuses more on other “security” issues: health security, supply chain and cybersecurity.

Has India decided that it still needs to retain strategic autonomy even if it has serious differences with China on its northern borders and therefore stepped away from the Quad as an Asian NATO? Or has the United States itself downgraded the Quad now that Australia has joined its geostrategic game of containing China?

AUKUS

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison on video with U.S. President Joe Biden during Sept. 15 announcement of the AUKUS pact. (C-Span clip)

Before the Quad meeting in Washington, the United States and the U.K. signed an agreement with Australia to supply eight nuclear submarines —the AUKUS agreement.

Earlier, the United States had transferred nuclear submarine technology to the U.K., and it may have some subcontracting role here. Nuclear submarines, unlike diesel-powered submarines, are not meant for defensive purposes. They are for force projection far away from home. Their ability to travel large distances and remain submerged for long periods makes them effective strike weapons against other countries.

The AUKUS agreement means that Australia is canceling its earlier French contract to supply 12 diesel-powered submarines. The French are livid that they, one of NATO’s lynchpins, have been treated this way with no consultation by the United States or Australia on the cancellation.

The U.S. administration has followed it up with “discreet disclosures” to the media and U.S. think tanks that the agreement to supply nuclear submarines also includes Australia providing naval and air bases to the United States. In other words, Australia is joining the United States and the U.K. in a military alliance in the “Indo-Pacific.”

Earlier, French President Emmanuel Macron had been fully on board with the U.S. policy of containing China and participated in Freedom of Navigation exercises in the South China Sea.

France had even offered its Pacific Island colonies — and yes, France still has colonies — and its navy for the U.S. project of containing China in the Indo-Pacific.

Please Support CN’s Fall Fund Drive!

France has two sets of island chains in the Pacific Ocean that the United Nations terms as non-self-governing territories — read colonies — giving France a vast exclusive economic zone, larger even than that of the United States.

The United States considers these islands less strategically valuable than Australia, which explains its willingness to face France’s anger. In the U.S. worldview, NATO and the Quad are both being downgraded for a new military strategy of a naval thrust against China.

Australia has very little manufacturing capacity. If the eight nuclear submarines are to be manufactured partially in Australia, the infrastructure required for manufacturing nuclear submarines and producing/handling of highly enriched uranium that the U.S. submarines use will probably require a minimum time of 20 years. That is the reason behind the talk of U.S. naval and air bases in Australia, with the United States providing the nuclear submarines and fighter-bomber aircraft either on lease, or simply locating them in Australia.

Maritime Powers

Ships from the navies of the U.S., Australia, India and Japan participate in Malabar exercises in the North Arabian Sea on Nov. 17, 2020. (U.S. Navy, Elliot Schaudt)

I have previously argued that the term Indo-Pacific may make sense to the United States, the U.K. or even Australia, which are essentially maritime nations.

The optics of three maritime powers, two of which are settler-colonial, while the other, the erstwhile largest colonial power, talking about a rule-based international order do not appeal to most of the world. Oceans are important to maritime powers, which have used naval dominance to create colonies. This was the basis of the dominance of British, French and later U.S. imperial powers. That is why they all have large aircraft carriers: they are naval powers that believe that the gunboat diplomacy through which they built their empires still works. The United States has 700-800 military bases spread worldwide; Russia has about 10; and China has only one base in Djibouti, Africa.

Behind the rhetoric about the Indo-Pacific and open seas is the U.S. play in Southeast Asia. Here, the talk of the Indo-Pacific has little resonance for most people. Its main interest is in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was spearheaded by the ASEAN countries. Even with the United States and India walking out of the RCEP negotiations, the 15-member trading bloc is the largest trading bloc in the world, with nearly 30 percent of the world’s GDP and population. Two of the Quad partners — Japan and Australia — are in the RCEP.

The U.S. strategic vision is to project its maritime power against China and contest for control over even Chinese waters and economic zones. This is the 2018 U.S. Pacific strategy doctrine that it has itself put forward, which it de-classified recently.

The doctrine states that the U.S. naval strategy is to deny China sustained air and sea dominance even inside the first island chain and dominate all domains outside the first island chain. For those interested in how the U.S. views the Quad and India’s role in it, this document is a good education.

A virtual Quadrilateral group summit with Australia, India and Japan at the White House on March 12. (White House, Adam Schultz)

The United States wants to use the disputes that Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia have with China over the boundaries of their respective exclusive economic zones. While some of them may look to the United States for support against China, none of these Southeast Asian countries supports the U.S. interpretation of the Freedom of Navigation, under which it carries out its Freedom of Navigation Operations, or FONOPS.

As India found to its cost in Lakshadweep, the U.S. definition of the freedom of navigation does not square with India’s either. For all its talk about rule-based world order, the United States has not signed the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) either.

So, when India and other partners of the United States sign on to Freedom of Navigation statements of the United States, they are signing on to the U.S. understanding of the freedom of navigation, which is at variance with theirs.

The 1973 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty created two classes of countries, ones that would be allowed to use a set of technologies that could lead to bomb-grade uranium or plutonium, and others that would be denied them.

There was, however, a submarine loophole in the NPT and its complementary IAEA Safeguards for the peaceful use of atomic energy. Under the NPT, non-nuclear-weapon-state parties must place all nuclear materials under International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards, except nuclear materials for nonexplosive military purposes.

No country until now has utilized this submarine loophole to withdraw weapon-grade uranium from safeguards. If this exception is utilized by Australia, how will the United States continue to argue against Iran’s right to enrich uranium, say for nuclear submarines, which is within its right to develop under the NPT?

India was never a signatory to the NPT, and therefore is a different case from that of Australia. If Australia, a signatory, is allowed to use the submarine loophole, what prevents other countries from doing so as well?

Australia did not have to travel this route if it wanted nuclear submarines. The French submarines that they were buying were originally nuclear submarines but using low-enriched uranium. It is the retrofitting of diesel engines that has created delays in their supplies to Australia. It appears that under the current Australian leadership of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Australia wants to flex its muscles in the neighborhood, therefore tying up with Big Brother, the United States.

For the United States, if Southeast Asia is the terrain of struggle against China, Australia is a very useful springboard. It also substantiates what has been apparent for some time now — that the Indo-Pacific is only cover for a geostrategic competition between the United States and China over Southeast Asia.

And unfortunately for the United States, East Asia and Southeast Asia have reciprocal economic interests that bring them closer to each other. And Australia, with its brutal settler-colonial past of genocide and neocolonial interventions in Southeast Asia, is not seen as a natural partner by countries there.

India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems to have lost the plot completely. Does it want strategic autonomy, as was its policy post-independence? Or does it want to tie itself to a waning imperial power, the United States? The first gave it respect well beyond its economic or military clout. The current path seems more and more a path toward losing its stature as an independent player.

Prabir Purkayastha is the founding editor of Newsclick.in, a digital media platform. He is an activist for science and the free software movement.

This article was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our

Fall Fund Drive!

I remain a bit confused. The author gave a fairly good overview of the geopolitical issues in West/Southwest Asia and the Indian subcontinent but I saw nothing explaining what India actually got out of “the quad”.