James DiEugenio looks through the accumulating murder evidence of a U.N. chief who might have changed the course of modern African history.

By James DiEugenio

Special to Consortium News

On the night of Sept. 17, 1961, U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld boarded his plane, the Albertina, in Leopoldville, as the capital city of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo was then known. He had authorized a mission that was unprecedented in U.N. history.

On the night of Sept. 17, 1961, U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld boarded his plane, the Albertina, in Leopoldville, as the capital city of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo was then known. He had authorized a mission that was unprecedented in U.N. history.

The U.N. had committed troops to put down a rebellion by a breakaway state called Katanga against the new African nation. Hammarskjöld was trying to arrange a cease fire between the U.N. forces and the Katangese mercenaries. He was to land at the Ndola airport in Northern Rhodesia, a British protectorate. His plane crashed several miles from the airport shortly after midnight on the 18th. In addition to the secretary general, 14 other people perished. One survivor died six days later.

Although the first local inquiry by British colonial authorities blamed the crash on pilot error, there have always been suspicions of foul play. A number of witnesses saw a large fireball explode in the sky around the airport. Before he died, the sole survivor, Harold Julien, said the plane was in flames before it crashed. More than one witness said they had seen a smaller plane behind and above the Albertina. But in spite of these observations the U.N.’s inquiry was inconclusive.

In 2011 English scholar Susan Williams’s book Who Killed Hammarskjöld? added evidence she had gathered by traveling the world. She described two servicemen, one Swedish and one American, who heard recorded messages saying that the second plane was in hot and hostile pursuit of the Albertina. She also wrote that witnesses saw Land Rovers driving to the scene of the crash within an hour.

In 2011 English scholar Susan Williams’s book Who Killed Hammarskjöld? added evidence she had gathered by traveling the world. She described two servicemen, one Swedish and one American, who heard recorded messages saying that the second plane was in hot and hostile pursuit of the Albertina. She also wrote that witnesses saw Land Rovers driving to the scene of the crash within an hour.

Other witnesses said they had reported the crash much earlier than the official time of discovery, which was 3 PM the next day. Perhaps her most memorable detail was this: Photos showing an unidentifiable playing card stuffed into the dead Hammarskjöld’s ruffled tie. A witness said it was the ace of spades.

Williams’s book was so well sourced and provocative that it caused a new U.N. investigation. That inquiry, now stretching over several years, has been stymied by lack of cooperation from countries including South Africa, the U.K. and the U.S.

New Documentary

The book, however, helped to renew interest in Hammarskjöld’s death and inspired the 2019 documentary, Cold Case Hammarskjöld, by Danish director Mads Brugger in consultation with Swedish investigator Goran Bjorkdahl.

Brugger begins his film with an animated depiction of the crash. He then cuts to a hotel room where he is dressed in white dictating the story of his search. With that narrative device, he lays out his his six-year search for the facts under chapter headings.

After providing some background on Hammarskjöld’s struggle to make the U.N. an effective advocate for nations emerging from colonialism, Bjorkdahl pulls the viewer into his field investigation.

Not only did witnesses see the plane in flames before it hit the ground, but they said the lights outside the airport went dim after the crash. The air traffic controller’s notes were lost and then reconstructed two days later. In an interview with the first civilian photographer on the scene, Bjorkdahl finds an oddity that Williams also noted: all the bodies were burned and charred — except Hammarskjöld’s. Was Hammarskjöld thrown from the plane on impact? We also learn that the Albertina was unguarded for two hours before it took off for Ndola. This had fostered suspicion that a bomb could have been planted on board.

The other suspected method of murder was fire from the following plane. The film investigates this aspect and focuses on the Belgian mercenary pilot Jan van Risseghem, nicknamed the Lone Ranger. Through declassified documents, we learn he had been suspected by the American ambassador to Congo, Edmund Gullion. But the filmmakers end up ruling this out when they learn through scientific testing of a metal plate from the Albertina that the holes were not made by bullets.

Operation Celeste

This prompts Brugger and Bjorkdahl to investigate a fascinating lead that was first uncovered by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Committee in 1998: Documents outlining a plot to kill Hammarskjöld codenamed Operation Celeste to which Williams devotes two chapters of her book.

The film shows the press conference at which South African theologian Desmond Tutu first publicized these documents. They originated in 1961 from an agency called the South African Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR). The Truth and Reconciliation Committee revealed that they were discovered in a file related to the 1993 assassination of Chris Hani, the leader of the South African communist party and chief of staff of the armed wing of the African National Congress.

The TRC did not conduct an extensive investigation or forensic testing to affirm the validity of the documents, which described a plot in which Hammarskjöld would be killed by means of some kind of air accident that SAIMR would be free to devise on its own. British intelligence and CIA Director Allen Dulles gave the SAIMR operation its green light, according to the documents. The plot calls for SAIMR to infiltrate the airport and to pull off the assassination more efficiently than that of revolutionary Congo leader Patrice Lumumba.

Still from “Cold Case Hammarskjöld.” (Trailer)

Operation Celeste consisted of two main techniques: planting a bomb on the Albertina, and having a fighter plane follow as a fallback if the bomb did not explode. The after-action report stated that the bomb did not go off upon takeoff, therefore the fighter plane followed. The bomb did, however, go off before the landing, according to the documents.

(The identity of the fighter pilot is uncertain. Although Risseghem, aka “Lone Ranger” is a key subject of the documentary, it was not necessarily him. Williams thought it could refer to Hubert F. Julian an African-American mercenary pilot who appears to have been in the employ of Moise Tshombe, leader of Katanga at the time.)

At the time of their exposure the documents were attacked by both British intelligence and the CIA as being planted forgeries, perhaps by the KGB.

Two Sources Go on Record

Williams had an unnamed source talk about the SAIMR operation. This film takes the exploration of SAIMR further. Brugger has two sources who agreed to be filmed. In addition, he found the family of a former member of SAIMR who was murdered.

The chief witness in the film is a former member of SAIMR named Alexander Jones. While employed by SAIMR, Jones said that he saw three pictures from the Hammarskjöld crash site. One of the living men he saw in a photo was Keith Maxwell, an action operative of SAIMR. The film reveals the only picture ever discovered of Maxwell. (Jones also saw an agent codenamed Congo Red, also involved in the group.)

The SAIMR agent who was murdered was a young woman named Dagmar Fiel. Bruggers tracked down Fiel’s brother and interviewed him extensively for the film. Fiel worked in SAIMR’s medical research lab. Jones, the former SAIMR operative, said that word had gotten out that she had second thoughts about what she was doing. Her brother said she predicted she was going to be killed. In 1990, she was.

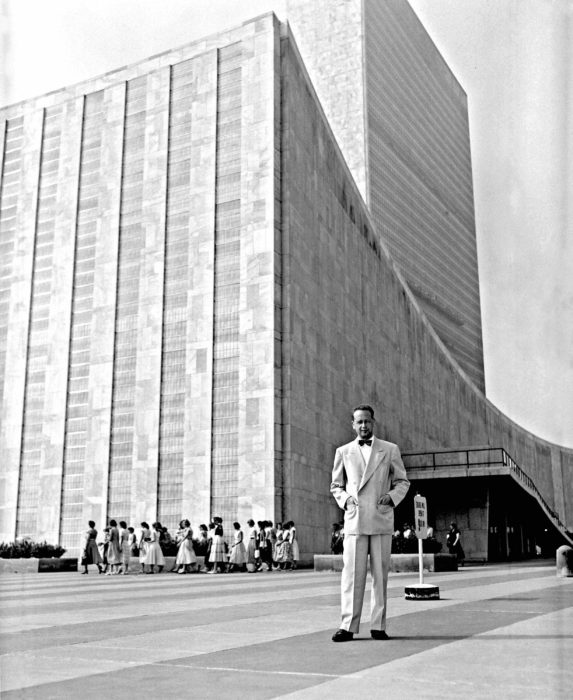

Dag Hammarskjöld outside U.N. building, 1953. (U.N./DPI)

While the family was investigating her killing, a SAIMR member approached them with papers. He told them they were part of a roman à clef by Maxwell. In that manuscript, Maxwell disguises the name of the supervisor of Operation Celeste as a man called “Wagman.”

Both Williams and Brugger understand this to be SAIMR operative Bob Wagner, a man whom Jones knew. The fictional Wagner outlines a plan that would include two options: a bomb on Albertina, and a fighter plane in reserve. That closely aligns with the SAIMR documents.

Dag Hammarskjöld believed his mission was to make the U.N. the representative of weak nations against the strong, which is why he was committed to Congo. President John Kennedy called Hammarskjöld the greatest statesman of the 20th century. The film argues that the history of modern Africa might have been different had he survived.

Thanks to Williams, and now Brugger, we are a lot closer to what actually happened. Perhaps the key piece of evidence is the playing card stuffed inside the U.N. chief’s shirt. When Jones is told of that, he immediately called it a recurring CIA motif that he recalled from other operations. With the accumulation of evidence that Williams and Bruggers provide, it’s hard to imagine anyone saying again that Dag Hammarskjöld was killed by “pilot error.”

James DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is The JFK Assassination : The Evidence Today.

Thanks Jason. The Hammarskjold case is greatly overlooked. Today I am convinced this was an assassination. Mainly due to the Congo crisis. Joe Lauria is to be saluted for being the only publisher to take notice of this key anniversary.

Characteristically brilliant analysis! Check out Jim’s website @ kennedysandking.com.