It now stands for torture chambers and car bombs, writes As`ad AbuKhalil. But there was a time when Ba’athists could have inherited the mantle of Nasser and the cause of Arab unity.

Gamal Nasser addressing crowds in Damascus in 1960, during the United Arab Republic period. (Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Wikimedia Commons)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

There was a time in Arab politics when the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party (Ba’ath is Arabic for renaissance or revival) was a dominant force in the region’s affairs.

There was a time in Arab politics when the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party (Ba’ath is Arabic for renaissance or revival) was a dominant force in the region’s affairs.

Even when Egypt’s Gamal Abdul-Nasser was the foremost leader of the Arab people from 1950s until his death in 1970, the Ba`th was a force to contend with.

The party was founded in 1947, two years after Syrian independence, by two Syrian intellectuals, Salah Al-Bitar and Michel `Aflaq. Both were influenced by the ideas and writings of Syrian intellectual Zaki Arsuzi, who died a bitter man because he felt, rightly, that his contribution to the Ba’ath ideology was forgotten or purposefully disregarded. (At one time he led his own Ba’ath Party.) Ba’ath ideology was a mix of Arab nationalism, socialism, non-alignment and anti-colonialism.

Syrian intellectual Zaki al-Arsuzi in the late 1930s. (The Online Museum of Syrian History, Wikimedia Commons)

In 1952, the Arab Ba’ath Party merged with the Arab Socialist Movement to become the Arab Socialist Ba`ath Party. The party swept through schools and colleges in Syria, Iraq, and other Arab countries. There was a party branch in every Arab country and its rhetoric left its mark on the region’s politics.

Challenges

The party, however, faced two major challenges. First, `Aflaq and Bitar lived in the era of Nasser, who overshadowed and marginalized friends and foes alike. Here were two obscure Damascene teachers competing with the most popular Arab leader since the time of Saladin (it would not be an exaggeration to say that Nasser, Saladin and Muhammad were the most popular Arabs ever).

Nasser preached Arab nationalism, as did the Ba’ath Party. But Nasser had a unique charisma and an ability to appeal to average people and intellectuals alike. The appeal of `Aflaq and Bitar was far more limited, confined largely to school and college students. `Aflaq was an eccentric man who did not feel comfortable in large crowds and seemed to enjoy the world of literature more than the political arena. He was a modest man who did not suffer from grand political ambition or a zest for power. He was more comfortable preaching the message of Arab nationalism in small gatherings.

Nasser did not like the Ba’ath Party and had a low opinion of its leaders, which only worsened over the years. The party was very influential in Syria and Iraq in particular (and in Lebanon and Gulf countries, but did not travel widely among the Palestinian people).

In the late 1950s, Syrian leaders approached Nasser to merge Egypt with Syria and create the first unification of two nations in modern Arab history. Nasser was hesitant and distrusted Baathist leaders who he accused of treachery and deception. But after a series of meetings, Nasser consented and the United Arab Republic (UAR) was founded in 1958.

The Arab popular response to the unity was massive and hundreds of thousands of people traveled from Lebanon to Damascus urging Nasser to include Lebanon in the new republic. (Nasser declined because he feared fragmentation and divisions in Lebanon and believed that Lebanon had a “special situation” in reference to its sectarian conflict). Nasser was president of the UAR while Baathist leader Akram Hourani, served as his non-ruling deputy.

Salah al-Din al-Bitar, cofounder of the Ba’ath Party, while serving as prime minister of Syria, March 1963. (Syrian History Archive, Wikimedia Commons)

The UAR project caused great consternation and alarm in Israel, Gulf monarchies and the West. The official or unofficial alliance between the tripartite sides goes back to the 1950s. They collaborated to bring down the UAR after just three years and humiliated Nasser with the help of wealthy merchants and landowners of Syria who opposed the socialist measures of the new regime.

The Egyptian government had also ruled Syria with a heavy hand through its secret police. Many Syrians saw their political profile being overtaken by Egyptian army officers. Western and Gulf intrigues followed and various attempts at overthrowing the regime were foiled. The Lebanese right-wing president at the time, Kamil Sham`un (a puppet of the U.S. and U.K.), collaborated with the West, Gulf countries, Jordan and Israel to undermine the new Republic.

A civil war ensued in Lebanon, and supporters of Nasser clashed with his foes, who received Western, Gulf, Jordanian and Israeli support. Sham`un failed to extend his presidential term and Nasser and the U.S. reached an agreement over the candidacy of Fu’ad Shihab, who became Lebanese president.

The second challenge to the Ba’ath Party was that while it preached Arab unity, the party itself split from the start into factions, offshoots and splinter groups. How could a party that could not unite its own ranks be able to convince the Arab people that it was the most qualified party to end the state of fragmentation and division of the Arab world?

The party suffered further in 1961 when a reactionary coup finally split Syria from the United Arab Republic, effectively bringing it to an end after just three years of existence. Nasser refused military plans to keep Syria by force. Bitar and Hurani also supported secession (al-infisal, the Arabic name for the split of the UAR in 1961). Though the union was over, Egypt retained the name of United Arab Republic until after Nasser’s death.

In Power

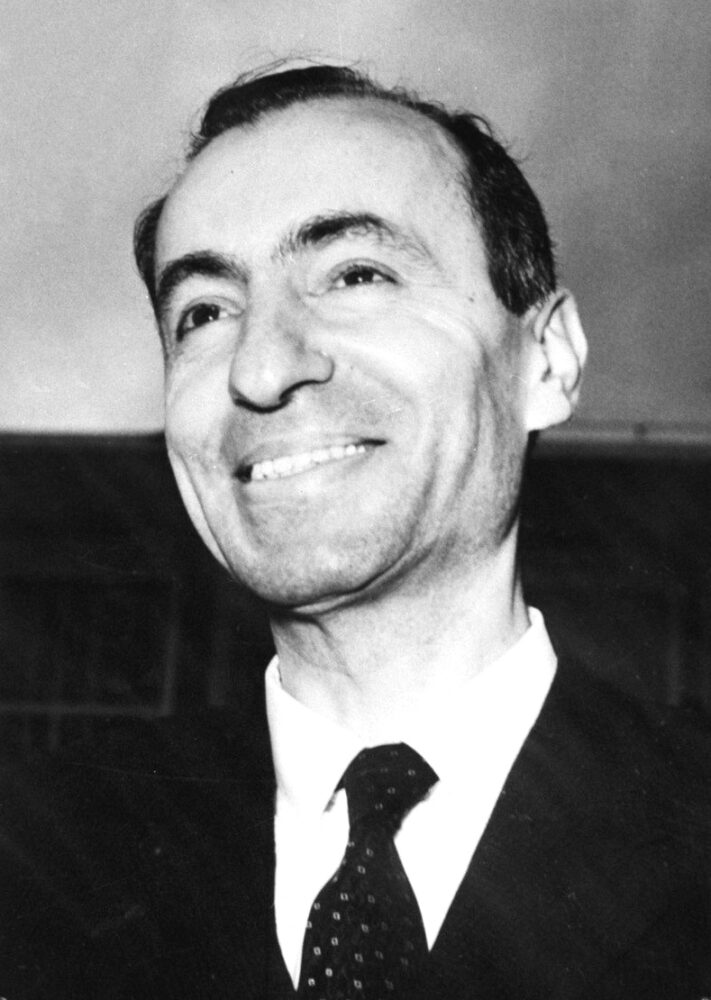

Michel ‘Aflaq, cofounder of the Ba’ath Party, in 1963. (Basch, Fritz; Dutch National Archives, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In Syria, the Ba’ath Party seized control in a 1963 coup. The party was ascendant in Iraq until 1968, when it firmly took over the country. After 1963, the Baathists yet again pleaded with Nasser to unite with Syria and Iraq. Nasser held long sessions with Baathists leaders (including `Aflaq) and the minutes of those sessions were published in Egyptian newspapers (and later released in book forms). The release of the minutes of “unity talks” dealt a severe blow to `Aflaq and the Ba’ath. The discussions put `Aflaq in a bad light. The minutes showed Nasser dominated the talks and the Ba`athists present were intimidated by him. Nasser made his distrust of the Ba’ath very clear and the talks went nowhere.

With the party taking power in Syria and Iraq, one would think it would dominate Arab politics. That was not to be, not only because Nasser dominated Arab politics until his death in 1970, but because the two parties had one of the longest and most bitter and violent feuds in the contemporary history of the region.

Both the Syrian and Iraqi regimes (which were ruled by different branches of the Ba’ath Party) sent hit teams against the officials of the rival camp. Vladimir Lenin wrote about feuds between different communist parties, but the feud between the two branches of the Ba’ath is legendary in the history of the region. They constructed gruesome repressive governments that were better known for torture techniques and suppression of the press than for campaigns of Arab unity.

The Ba’ath Party in Iraq was ousted from power by the 2003 U.S. invasion, although there are still people in Iraq who speak on behalf of its ideology. There are still Ba`athist personalities and organizations throughout the Arab world, but their influence is rather negligible.

The party that once symbolized sincere efforts at Arab unity now stands for torture chambers and car bombs.

In Syria, the name of the party has been sullied to such a degree, that even the ruling regime has been downplaying its role — although it remains formally the ruling party. There was a time when the Ba’ath Party could have inherited the mantle of Nasser, but it was already damaged by 1970.

Within Syria and Iraq, there were splits and schisms within the party, but nothing that an assassination here or a car bomb there would not settle it. For all intents and purposes, the Ba’ath Party is a relic of history. It earned that status, and had little merit to seize power in any Arab country.

A party that promoted Arab unity will be remembered for driving the Arabs further apart.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002) and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

According to Wikipedia, Saladin was a “Sunni Muslim Kurd” – who ruled both Syria and Egypt in the 12th Century. That agrees with my prior impression.

A leader of Arabs, but not an Arab.

For much of its existence, the ideals and virtues of the Ba’ath outweighed its faults, But “the victors write the history,” so only scholars will note the party’s progressive policies. Too bad, how our pettiness so often obliterates our best intentions.

I have learned more about the history of the Middle East by reading CN, especially Professor Abu Khalil, than from all other sources combined. Thank you for this very thoughtful essay.

yep

Could attempting to combine nationalism with socialism have been the Ba’ath’s poison pill from the beginning?