The public sentiment is that the “stimulus” was largely looted, writes Busi Sibeko in this argument for ending austerity.

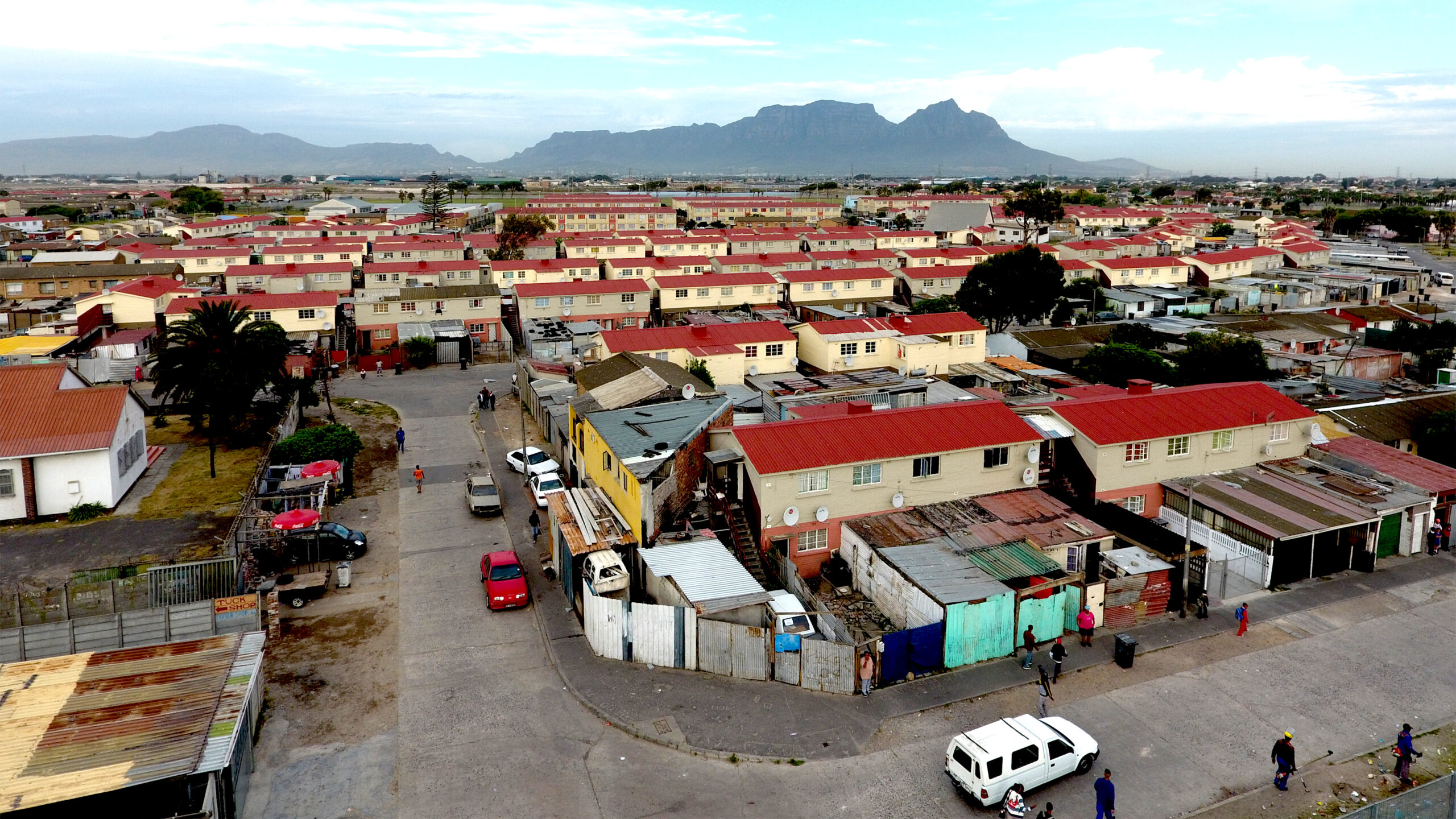

Apartments in Manenberg Township, Cape Town, South Africa, built by the apartheid-era government and shown here in 2017. (Discott, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Busi Sibeko

International Politics and Society

On July 7, the arrest of the former South African President, Jacob Zuma, plunged the country into a new wave of violent protests and looting. To date, at least 200 people have lost their lives, more than 2,554 arrests have been made and 50,000 businesses have been damaged or impacted.

While the Zuma protests may have been the trigger, they are not the sole cause, nor are they what underpin the popular element of the widespread violent protests and looting South Africa has experienced over the last two weeks.

After almost three decades of democracy, South Africa faces multiple crises. The country has world-leading level of inequality, with a Gini coefficient for income distribution of 0.7. Wealth is even more unequally distributed with the wealthiest one percent of the population owning half of all wealth, while the top 10 percent own at least 90–95 percent.

The Outcome of a Decade of Recession

The consequence of a lack of structural transformation in South Africa meant that the country was in a precarious economic position even before the pandemic. Stubbornly high levels of unemployment were already at 29.1 percent in the end of 2019. Poverty remains unconscionably high. In 2015, over half of the population — 30.4 million people — lived below the official poverty line, higher for female-headed households than male-headed households (49.9 percent versus 33.0 percent). A quarter — 13.8 million people — lived in “extreme poverty,” unable to afford enough food to meet their basic physical needs.

Volunteers preparing food parcels in Philippi, Western Cape, an area of South Africa that was hit hard by the lockdown. (Discott, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

South Africa’s growth has trended downwards since 2010, averaging just 1.7 percent between 2011 and 2018. In 2019, South Africa was plunged into its third recession since 1994.

Precipitating factors included: the global downswing following the global financial crisis, declining commodity prices, deindustrialisation, “state capture” (that is, systemic corruption), budgetary cuts, restrictive macroeconomic policies, slowed investment as a result of economic stagnation, and insufficient electricity supply and resultant blackouts, amongst others.

Economic crises have enabled and fuelled our political crises. Growing numbers of people are perceiving the state as a vehicle for predatory accumulation, aided by corrupt actors in the private and public sector. This reality underlies the acute crisis of governance and state capture in South Africa, marked by looting and the undermining of public institutions. Taken together, these economic and political crises are eroding confidence in the constitutional dispensation.

The Pandemic

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa on July 2, arriving in Lusaka for the funeral of Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda. (GovernmentZA, Flickr)

The Covid-19 crisis came at a time when South Africa was already in a recession. In April 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced South Africa’s 500 billion Rand rescue package aimed at supporting workers, businesses, and households through the pandemic. The package offered a glimmer of hope for the country; however, this was short lived. The programme saw numerous problems in implementation. As of July 2021, less than half of the budget has been materialised.

The problem was that there were no 500 billion Rand to begin with. The 2020 supplementary budget presented a net increase to non-interest spending of just 36 billion Rand, or less than one percent of GDP. Most of the rescue package therefore came from existing funds or off-budget expenditure. The deliberate misleading of citizens into believing that hard cash was pumped into the economy is one of the factors fuelling the violent protests. The public sentiment is that the “stimulus” was largely looted.

Please Support Our Summer Fund Drive!

South Africa is now in its third wave of Covid-19 infections. Most of the relief measures have expired. At the same time, Covid-19 infections continue to rise as the government rolls out its vaccination programme.

A third wave of the pandemic, and lockdowns, in South Africa comes at a time when most vulnerable groups have lost income and are living under immense hardship.

Shelves in a grocery store in Johannesburg lay bare due to panic buying amidst the 2021 South African unrest. (Aleksandar Bulovic, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

According to a recent survey, 39 percent of households ran out of money to buy food in January and 17 percent of households experienced weekly household hunger. The special Covid-19 “Social Relief of Distress” (SRD) grant — a cash distribution to unemployed adults not receiving other social security — introduced in the initial relief package has been terminated. Food price inflation has increased.

School feeding programmes which many children rely on are closed. And now, with the current violence, some areas are plagued with food shortages.

As this third wave progresses, economic activity is expected to contract — even more now with the current violent protests — with the likely fallout for workers, businesses, and communities. After a seven percent economic contraction in GDP in 2020, the economy continues to shed jobs as the unemployment rate reaches a record high of 32.6 percent. The current protests will only exacerbate the crises that have partly led to the popular element of the protests themselves, creating a vicious cycle.

Austerity at All Costs

Despite the threat of multiple socio-economic crises, South Africa’s National Treasury has remained committed to its austerity programme — the cutting of expenditure to address debt during economic downturns — endorsed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and much of the business press.

Since 2014, the South African government has introduced austerity measures in an attempt to reduce debt levels and to appease credit rating agencies. This has severely undermined the provision of essential social service and the realisation of socio-economic rights. Even in the midst of the civil unrest this policy is being reenforced.

South Africa’s national parliament building in Cape Town. (Janek Szymanowski, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

It is likely that the government of South Africa will press on with its plans to consolidate non-interest expenditure (spend on everything but debt) by an annual real average rate of 5.2 percent, as announced in February.

Cuts to the budget entail a fall in spending per person and leads to real reductions in health, learning and culture, and general public services. The president recently indicated that any new emergency relief measures would be provisioned within the existing budget limits. Given the pressing social needs, enormously exacerbated by Covid-19 and now the violent protests, this is deeply irresponsible.

Dealing with Root Causes

The South African government has largely gone from crisis to crisis without fundamentally dealing with the political and economic root causes of the crises themselves.

The political party factionalism within the ruling African National Congress needs to be resolved decisively. The factionalism is a liability to the nation. This must be coupled with a recommitment to the 1955 Freedom Charter and the Constitution of South Africa, which foresee a fairer economic dispensation as a critical component of political liberation.

In the immediate term the South African government needs to protect livelihoods and sustain the economy. Previously terminated relief measures to support business, workers and households must be renewed and adapted to respond to the Covid-19 crisis as well as the current crisis the country faces.

Such measures are not possible with the current austerity agenda that has been adopted. The austerity course must be abandoned and socio-economic rights prioritized. This approach must be coupled with meaningful economic transformation that serves the majority. For all we have now, is not even a shadow of political liberation.

Busi Sibeko is an economist at the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) in Johannesburg. She researches macroeconomic policy.

This article is from International Politics and Society.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our

Summer Fund Drive!

Show Comments