Richard C. Bush has helped preserve peace between Beijing and Taipei. But as Gareth Porter reports, he changed his position.

Richard C. Bush moderating a Brookings Institution panel in 2019. (Brookings Institution, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Why did the top think tank Taiwan specialist ignore a longstanding U.S. policy that blocked any move by the Taiwanese leader that might have disrupted the political basis for China-Taiwan cooperation? And why did he give a free pass to the leader of Taiwan’s separatist party?

Why did the top think tank Taiwan specialist ignore a longstanding U.S. policy that blocked any move by the Taiwanese leader that might have disrupted the political basis for China-Taiwan cooperation? And why did he give a free pass to the leader of Taiwan’s separatist party?

An investigation into that turnabout by Richard C. Bush of the Brooking Institution reveals a previously unknown story of an Obama administration policy shift away from one of the bedrock principles that guided U.S. policy toward Taiwan.

The historic understanding between the United States and China over the status of Taiwan initiated by President Richard Nixon and every subsequent U.S. administration was based on the one China principle which China has insisted upon, along with the recognition of People’s Republic of China and the de-recognition of the anti-Communist regime on Taiwan.

Beginning in the 1990s, the U.S. government had urged the Taiwanese government to stop publicly flouting the one China principle. But President Tsai-Ing wen, first elected 2016 as the candidate of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), consistently refused to accept the demands.

Her obstinate stance seriously eroded the stability in cross-Strait relations that prevailed under the Nationalist government of Ma Ying-jeou from 2008 to 2016. As a result, Taiwan has turned from a source of U.S.-China cooperation into a dangerous geopolitical friction point.

Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen in 2020. (Office of the President, Flickr, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

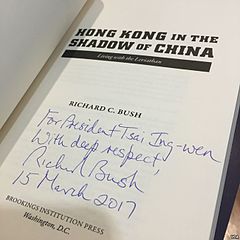

Described by former Brookings President Strobe Talbott as “quite simply America’s leading Taiwan hand,” Richard C. Bush played a key role in legitimizing this quiet U.S. shift in Taiwan policy. The story of how Bush accepted Tsai as a serious interlocutor for cross-Strait relations, despite the Taiwanese leader’s ties with a firmly established separatist wing of the DPP, helps explain the dramatic rise in Sino-U.S. tensions over Taiwan since in 2016.

As this previously untold story reveals, Bush was encouraged to do so by Obama administration officials.

Taiwanese Leaders Deterred

Before joining Brookings in 2002, Bush was one of the U.S. government’s leading hands on China and Taiwan. He served as the CIA’s national intelligence officer for East Asia from 1995 to 1997, then became the director of the American institute in Taiwan (AIT) — the unofficial U.S. government representation in Taiwan created in 1979 after the U.S. de-recognition of the Republic of China.

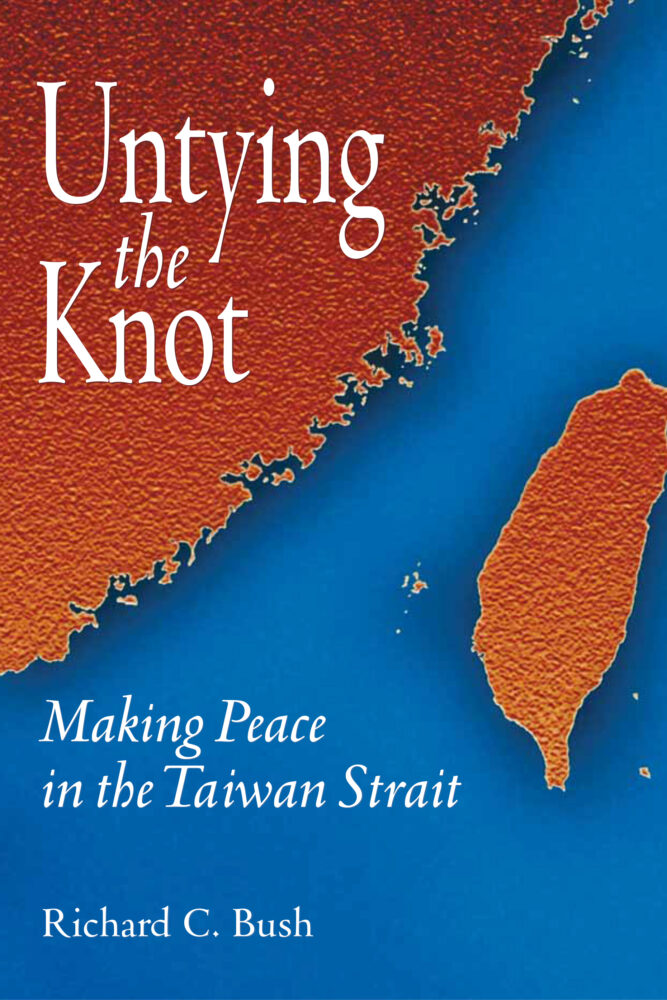

In his 2005 book, Untying the Knot, Bush acknowledged that unofficial delegations from Taiwan and China had agreed on the concept of “one China, two systems” as the political basis for discussion of cross-Strait cooperation. They called it “the 1992 Consensus.”

In his 2005 book, Untying the Knot, Bush acknowledged that unofficial delegations from Taiwan and China had agreed on the concept of “one China, two systems” as the political basis for discussion of cross-Strait cooperation. They called it “the 1992 Consensus.”

U.S. officials were concerned, however, that top Taiwanese officials were taking provocative positions on Taiwan’s political-legal status that risked a blow-up with China, knowing they could count on the United States to protect the island from China.

Those worries prompted the U.S. to issue a policy called “dual deterrence” designed to deter Beijing from attacking Taiwan, while reassuring China that Washington would not support any moves toward Taiwanese independence.

The policy also cautioned Taipei against moves that would “unnecessarily provoke a Chinese military response,” as Bush put it, while promising Taiwan that it would not have to sacrifice its interests in order to ensure good relations with Beijing.

Bush revealed in December 2015 that the United States had applied the policy on three occasions over positions taken by Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidates.

The first time came in 2003, when President Chen Shui-bian’s statements and actions indicated to U.S. officials that he might unilaterally “change the status quo” by moving toward Taiwanese independence. In response, a State Department official warned Chen in 2008 against policies that would unnecessarily put Taiwan’s security at risk.

Tsai Ing-wen in 2008, while chairperson of the Democratic Progressive Party. (sfmine79, Flickr, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Next, in 2011, when Tsai Ing-wen was running for the first time as DPP candidate for president, the Obama administration expressed “distinct doubts” that cross-Strait stability would continue under a DPP government.

Bush did not mention another instance in which he was personally involved as director of the AIT: in a 1999 interview, then-President Lee Teng-hui had presented his “state to state” theory of Taiwan-China relations. Beijing was outraged, immediately branding his rhetoric as “separatist.” Bush was dispatched to Taipei from Washington with a stern U.S. warning against such talk, promptly shutting down Lee’s separatist concept.

Obama Policy Shift

Richard C. Bush suggested in December 2015 that the Obama administration would likely have to implement the same “dual deterrence” policy once the likely winner of the 2016 presidential election, DPP leader Tsai Ing-wen, took power.

During her campaign, Tsai had avoided taking a clear stance on the 1992 Consensus and the “one country” principle. Instead, she expressed support for the “status quo” while refusing to explain what that meant in practice.

Please Support Our Summer Fund Drive!

Bush noted that she had good reason to obscure her real policy toward the PRC. After all, a 2014 DPP-sponsored poll revealed that 60 percent of Taiwanese who had a position on cross-Strait policy favored the KMT’s status-quo position and only 40 percent supported the DPP policy.

Furthermore, China’s PRC had attacked her as early as 2000 as “Taiwan separatist Tsai,” noting that she had openly supported Chen’s “one country on each side” of the Taiwan Strait, and had attacked then President Ma Ying-jeou’s policy as “selling Taiwan to China.”

In 2011, when Tsai was running for DPP chair, she declared flatly, “There is no 1992 Consensus.” Instead, she proposed a “Taiwan Consensus” — a position viewed by the Obama administration as unacceptably risky.

Abrupt Reversal

But in April 2016, just before Tsai’s inauguration, Bush abruptly reversed his position of a few months earlier and supported Tsai’s refusal to clarify her stance on the 1992 Consensus.

There was no ambiguity about where the Taiwanese leader stood. As Bush explained, Tsai could not accept the 1992 Consensus on which China had long insisted as the basis cross-Strait cooperation, because to do so would alienate the “true believers” in the DPP and split the party.

That, of course, was exactly the kind of internal Taiwanese political threat to the stability of cross-Strait relations that the “dual deterrence” policy had been created to deal with. Nevertheless, Bush blamed the impasse on Beijing.

In calling for Tsai’s adherence to the 1992 Consensus and the “one China” principle, Bush wrote, China was demanding “a high degree of clarity from her.” Further, he suggested, “Perhaps [China’s] strategy is to set the bar so high that she can’t clear it.”

In fact, Beijing was applying the same criterion to Tsai as it had to Taiwanese governments in the past. The difference now was that Tsai had rejected what previous governments had accepted.

Military Push for ‘Great Power Competition’

In a series of responses to e-mail queries from The Grayzone, Bush attributed his April 2016 rejection of the “dual deterrence” policy to Tsai to a shift by Obama officials. “Obama administration officials were more confident about Tsai’s intentions in 2015-16, than they had been in 2011-12, when Tsai also ran for president,” Bush wrote.

Behind that Obama administration decision to tolerate Tsai’s refusal to honor the 1992 Consensus lies a larger story: the Obama administration adopted its position just when domestic U.S. political and bureaucratic inertia was shifting towards a confrontation with Beijing over military issues. Indeed, Obama’s shift came during a period of growing pressure on the White House from the U.S. military, the Pentagon and Republicans in Congress to take a harder line on China.

In mid-2015, the commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Harry Harris began pushing publicly for a tough U.S. response to Chinese military construction on artificial islands the PRC claimed in the South China Sea.

Nov. 3, 2014: Adm. Harry Harris Jr., commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet, being awarded the Korean Tong-is national defense medal by Republic of Korea Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Hwang Ki-chul in Seoul. (U.S. Navy, Frank L. Andrews)

Harris argued for U.S. “freedom of navigation” operations within the 12-mile limit claimed by Beijing. That demand was supported by the Pentagon and Senate Armed Services Committee chairman, Sen. John McCain, who was complaining of the Obama administration “de facto recognition” of those Chinese claims.

The White House remained silent on the issue, resisting such operations until October 2015, when President Barack Obama approved the first of several more over the following year.

Aug. 4, 2016: left to right: Vice President Joe Biden, President Barack Obama and Secretary of Defense Ash Carter greet one another ahead of a meeting at the Pentagon. (DoD, Brigitte N. Brantley)

Meanwhile, another conflict was brewing between the White House and then-Defense Secretary Ashton Carter over whether to identify China as a strategic competitor with the United States. Privately, Obama argued against publicly declaring “strategic competition,” but for the Pentagon, the designation was necessary to generate congressional support for more defense spending.

In February 2016, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter foreshadowed a “return to great power competition” and vowed to counter the “rising” Chinese power. Though the White House had ordered the Pentagon not to use such provocative rhetoric, the political ground had already shifted in favor of the military’s position.

In an email to The Grayzone, Bush said, “I don’t know everything that went into the thinking of Obama officials on Tsai, specifically the nature and degree of Pentagon or congressional pressure.” He added that he did not recall whether pressure from the military was a factor in the decision not to intervene.

Yet it is hard to believe that big-ticket issues like the defense budget did not impinge on the narrower decision not remain passive in the face of Tsai’s separatism.

The consequences of that fateful decision have continued to accumulate, especially since Tsai’s reelection in 2020. China has made it clear that it plans to impose higher economic and psychological costs on Taiwan over Tsai’s rejection of the one-China principle.

It has begun a campaign of frequent intrusions by PLAF fighter planes into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), aimed at underlining Taiwan’s vulnerability and forcing the Taiwanese population to consider whether the DPP’s flirtation with an independent Taiwanese state is worth the cost.

A new Taiwan crisis looms in 2023-2025 in the likely scenario that Tsai’s Vice-President William Lai — the leader of the separatist wing of the DPP — becomes the DPP presidential candidate in the 2024 election.

The question of “dual deterrence” will be raised again, but with much higher stakes.

Gareth Porter is an independent investigative journalist who has covered national security policy since 2005 and was the recipient of Gellhorn Prize for Journalism in 2012. His most recent book is The CIA Insider’s Guide to the Iran Crisis, co-authored with John Kiriakou, just published in February.

This article is from The Grayzone

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our

Summer Fund Drive!

You know, funding the US War of Independence is one of the main triggers to the French Revolution, all it’s violence, ending in Napoleon’s dictatorship. Constant militarism can’t be good for the US elite, in the long term.

Too bad the US doesn’t set an example, return independence to Hawai’i, return the Black Hills to the Sioux, etc., etc.

Indeed, Obama’s shift came during a period of growing pressure on the White House from the U.S. military, the Pentagon and Republicans in Congress to take a harder line on China.

The military initiation of the anti China Pivot to Asia. Vital context when trying to understand where we have got to , and why the chinese built their own Diego Garcia. A context that is deliberately not presented by our state friendly media.

Author Porter has not a word of objection as he narrates how the U.S. imperialists give orders to Taiwan as though it is a colony. That is the price of ignoring PRC expansionism: the anti-imperialist is alarmed that the U.S. is not imperialist enough toward Taiwan today.

While never entirely the same as the mainland in culture, dialect, and attitude to Han ethnicity, Taiwan was once a true part of China in substance. But the mainland and Taiwan have evolved along different paths for a long time now. This reality must be taken into account.

The problem is that the DPP’s independence project is inseparably tied to the American imperial project in the “Indo-Pacific”. Tsai’s goal is to secure Taiwanese independence by becoming an American military garrison state, the tip of the spear of US imperial aggression toward China that is very much on the move. Beyond the sensitive territorial claims, a Taiwan that is fully backed by the US military, possibly with bases and missiles, just off the coast of mainland China is easily seen as a Cuban Missile Crisis-type provocation. Think about the OFFENSIVE capability this provides the US empire, the same way Ukraine’s desire to join NATO and hosting bases and missiles would be extremely provocative towards Russia’s security if indulged.

Like Israel, Taiwan exists as a nation because of support from the US, UK and a small number of allies, because of its geopolitical utility. The question is, will US planners use Taiwanese nationalists to push the blade closer to mainland China (risking the Taiwanese population in the process), or will they manage the situation to avoid conflict? In 2021 we already know the answer.

Tp “becoming an American military garrison state” is not a good thing. Look at the Phillipines, right next door.