Part three of a six-part series on Julian Assange and the Espionage Act.

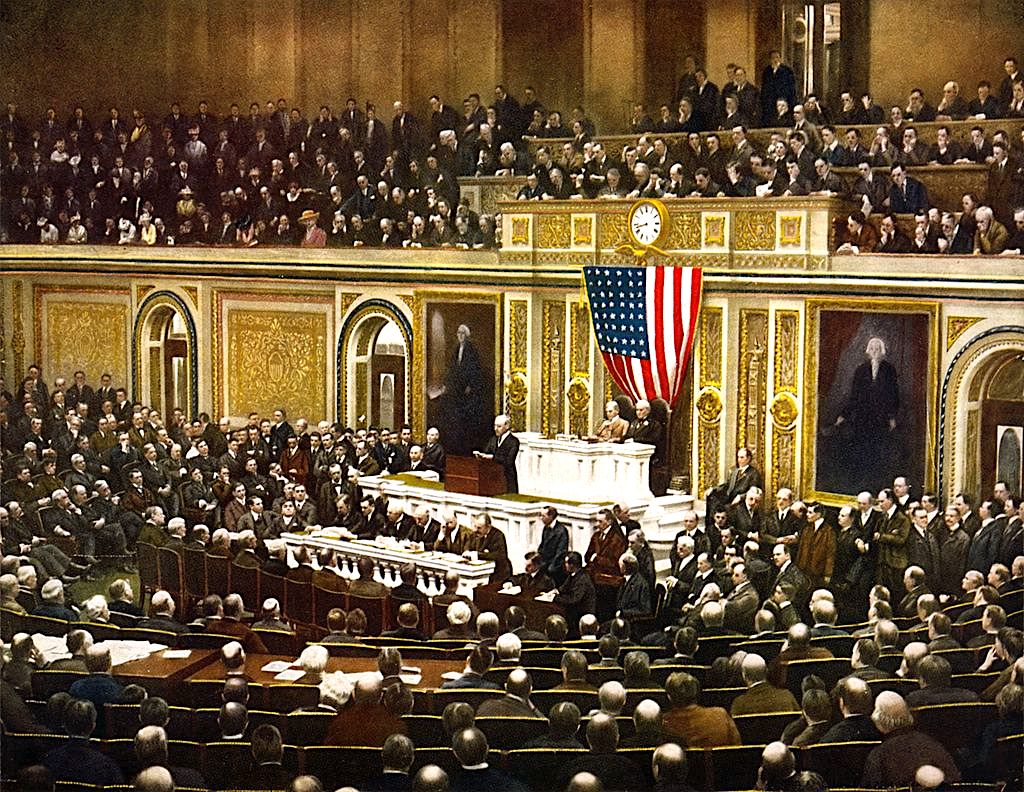

Wilson asking Congress to declare war on Germany, April 2, 1917, the very day the Espionage Act bill was introduced. (Colorized Wikimedia Commons)

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

In his 1915 State of the Union address, in the midst of the First World War, but before the U.S. entered it, President Woodrow Wilson made a strident and authoritarian argument for the Espionage Act. He said:

“There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt, to destroy our industries wherever they thought it effective for their vindictive purposes to strike at them, and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue…

I urge you to enact such laws at the earliest possible moment and feel that in doing so I am urging you to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation. Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out. They are not many, but they are infinitely malignant, and the hand of our power should close over them at once. They have formed plots to destroy property, they have entered into conspiracies against the neutrality of the Government, they have sought to pry into every confidential transaction of the Government in order to serve interests alien to our own. It is possible to deal with these things very effectually. I need not suggest the terms in which they may be dealt with.”

On the very day Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, Sen. Charles Allen Culberson, a Texas Democrat, introduced the Espionage Act bill to the Senate.

Formal Censorship Rejected

While the Espionage Act does not impose formal government censorship, its use against Assange is having a chilling effect on the press and the spirit, if not the letter, of the First Amendment. While the Pentagon Papers case, as we’ll see, showed that the government cannot exercise “prior restraint” — that is, ordering a publisher beforehand not to publish classified material — it can prosecute a publisher or journalist after publication.

If Wilson had had his way, however, prior restraint — or formal government censorship — would have become legal. He sent Congress a version of the Espionage Act that explicitly called for it.

There was a furious reaction against it in the press.

A June 1919 article in the Michigan Law Review reported:

“Said The MILWAUKEE NEWS … The Censorship bill . . . has aroused such a storm of dis- approval that the President seeks to allay popular indignation at this glaring attempt to void Constitutional rights. . . . The whole program to muzzle the press seems to smack of unconstitutionality, tyranny, and deceit.’

“The NEW YORK TIMES, too, was greatly alarmed, and devoted a considerable part of its editorial space throughout several days to criticism of the measure and especially of its alleged unconstitutionality.”

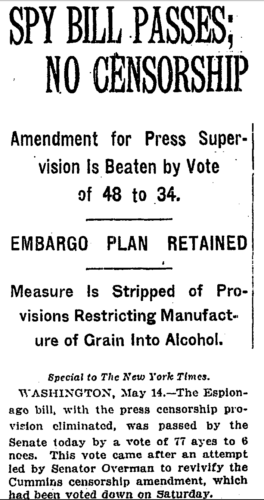

After just one week of debate, the Senate was sufficiently alarmed that it voted 39 to 38 to remove the section on censorship. A single Senate vote stopped formal U.S. censorship.

The Espionage Act bill was passed by the House on May 4, 1917, by 261 votes to 109 and by the Senate on May 14 by a vote of 80-8. Passage in the Senate came with a warning from Democratic Sen. Charles Spalding Thomas of Colorado, who said: “I very much fear that with the best of intention we may place upon the statute books something that will rise to plague us in the immediate future.” He added:

“Of all times in time of war the press should be free. That of all occasions in human affairs calls for a press vigilant and bold, independent and uncensored. Better to lose a battle than to lose the vast advantage of a free press.”

“‘The whole program to muzzle the press seems

to smack of unconstitutionality, tyranny, and deceit.'”

Sen. James Watson of Indiana raised the issue of criminalizing mere possession of defense information by a journalist:

“Suppose a newspaper correspondent were to go into the office of the Secretary of War and talk to him about the number of troops that were in a certain division or under a certain command, or about the movement of those troops, whether that information is ever used or not, whether it is ever published or not, under the terms of this provision that in and of itself makes him guilty of a violation of the statute.”

Wilson signed the final version of the Espionage Act on June 15, 1917. But in a signing statement he nevertheless insisted that: “Authority to exercise censorship over the press … is absolutely necessary to the public safety.”

Though formal censorship was rejected, the conflict with the First Amendment was not resolved. The adopted language was broad enough to make “whoever” liable to prosecution. That could include any journalist who obtains defense information with “intent or reason to believe” that it would injure the U.S. and who “willfully communicates or transmits or attempts to communicate or transmit the same to any person not entitled to receive it.” It also makes liable anyone who “willfully retains” defense information and fails to deliver it “on demand” of a government officer. The penalty was a fine of no more than $10,000, two years in prison, or both.

The phrase “with intent or reason to believe” is broader than the 1911 OSA’s “intended to be directly or indirectly useful to an enemy.” The Defense Secrets Act says nothing about intent.

In his indictment, Assange is charged with obtaining, retaining and disclosing defense information.

The foundation of the offenses Assange has been accused of committing — unauthorized possession and disclosure — are present in the Acts so far considered.

1918 Sedition Act

Not satisfied that censorship was excluded, Wilson pushed for an amendment to the Act that was passed by Congress (48-26 in the Senate and 293-1 in the House). The Alien and Sedition Act was enacted on May 16, 1918, just months before U.S. troops arrived on the Western Front in the First World War. Though it was called an act, it never stood alone as one, but became part of the Espionage Act.

Not satisfied that censorship was excluded, Wilson pushed for an amendment to the Act that was passed by Congress (48-26 in the Senate and 293-1 in the House). The Alien and Sedition Act was enacted on May 16, 1918, just months before U.S. troops arrived on the Western Front in the First World War. Though it was called an act, it never stood alone as one, but became part of the Espionage Act.

Wilson had the backing of influential congressmen and newspaper publishers who wanted to shut down certain speech. The Sedition Act curtailed speech especially of Americans who opposed U.S. participation in the war and particularly the draft. More than 4 million Americans fought and 110,000 died in the war. (The act may have influenced U.S. newspapers to suppress news of the 1918 flu pandemic in deference to the war effort.)

The Sedition Act’s two-paragraph amendment to the Espionage Act was specifically aimed at Americans who insulted the U.S. government, military or flag and tried to criticize the draft, military industry or sale of war bonds. It said:

“…whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States, or the flag of the United States, or the uniform of the Army or Navy of the United States into contempt, scorn, contumely, or disrepute, or shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any language intended to incite, provoke, or encourage resistance to the United States, or to promote the cause of its enemies, or shall willfully display the flag of any foreign enemy, or shall willfully by utterance, writing, printing, publication, or language spoken, urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of production in this country of any thing or things, product or products, necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war in which the United States may be engaged, with intent by such curtailment to cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of war, and whoever shall willfully advocate, teach, defend, or suggest the doing of any of the acts or things in this section enumerated, and whoever shall by word or act support or favor the cause of any country with which the United States is at war or by word or act oppose the cause of the United States therein, shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or the imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both…”

It also empowered the postmaster general to intercept and return mail to its sender stamped with the words

“Mail to this address undeliverable under Espionage Act.”

This law distilled the essence of enforced loyalty of the population to the symbols and military power of the state. It demolished the idea that America is exceptional as it showed the U.S. enforcing the same state-worship as most nations in history.

Though he is not an American and the Sedition Act is no longer on the books, it is this disloyalty to the dictates of the American state that Assange is being punished for as his extradition hearing prosecutors failed to demonstrate his work caused harm. (Today’s sedition law relates to two or more people who conspire to overthrow the U.S. government.)

Espionage and Sedition Act Prosecutions

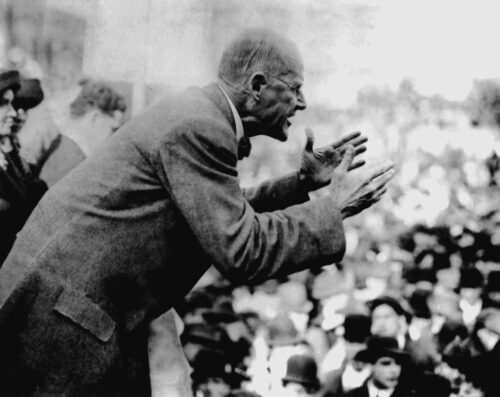

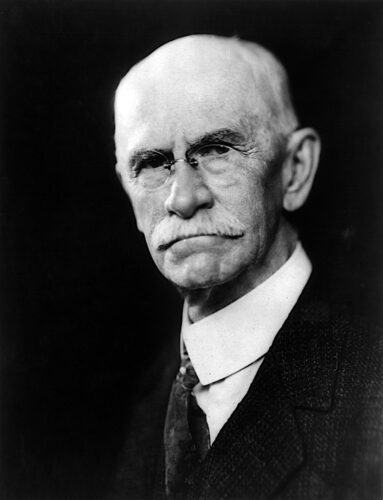

Debs at a 1918 rally, shortly before being arrested for sedition for opposing the draft. (Wikimedia Commons)

The act, with similar federal laws, was used to convict at least 877 people in 1919 and 1920, according to a report by the attorney general. In 1919, the Supreme Court heard several important free speech cases — including Debs v. United States and Abrams v. United States — involving the constitutionality of the law. In both cases, the Court upheld the convictions as well as the law.

The best-known Sedition Act prosecution was the socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs. A month after the 1918 Sedition Act was passed was passed on May 16, 1918, Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison for publicly opposing the military draft. In a June 1918 speech he had said: “If war is right let it be declared by the people. You who have your lives to lose, you certainly above all others have the right to decide the momentous issue of war or peace.”

While in jail Debs received one million votes for president in the 1920 election. Assange’s defiance of the U.S. government went well beyond Debs’ anti-war speech by uncovering war crimes and corruption.

For being seditious, Debs and Assange are the most prominent political prisoners in U.S. history.

The Schenck Case

Before the Sedition Act, Charles Schenck, the general secretary of the U.S. Socialist Party, was arrested in 1917, and convicted under the Espionage Act for mailing fliers to draft-age men opposing the First World War conscription.

He was charged with language from Section 3 of the Espionage Act that made it illegal to “make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States” and to “cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces … or … willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States.”

Schenck’s appeal on First Amendment grounds went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in March 1919 that his conviction did not violate free speech.

It was a significant decision, rolled back somewhat in 1969 by the First Amendment case Brandenburg v. Ohio, in which the Supreme Court ruled the government could only punish inflammatory speech if it is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Espionage Act indictment against Assange doesn’t allege that, other than a very weak and fraught U.S. claim Assange “intentionally” risked the lives of U.S. informants.

The ruling in Schenck’s case was a significant defeat for the First Amendment against the Espionage Act. But it did not deal with the possession and publication of classified material that Assange has been charged with. Since no journalist had ever been charged with this before, Assange’s appeal on First Amendment grounds, if it goes that far, would also be a first.

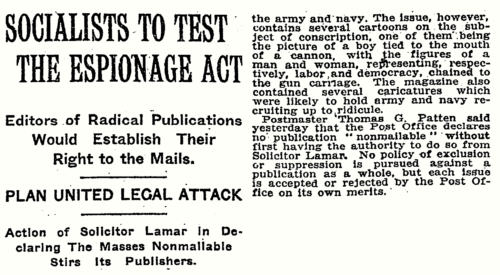

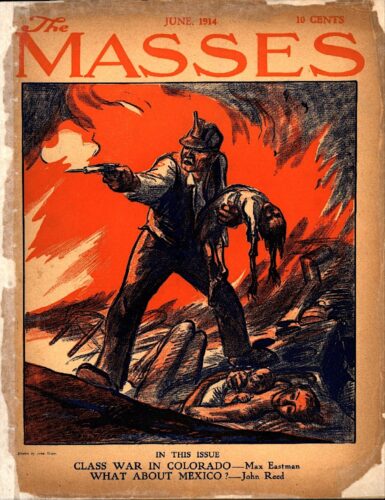

The Masses

A magazine called The Masses was prosecuted in 1918 for interfering with the military draft. The magazine published some of the leading left-wing writers of the day, including Max Eastman, John Reed and Dorothy Day.

A magazine called The Masses was prosecuted in 1918 for interfering with the military draft. The magazine published some of the leading left-wing writers of the day, including Max Eastman, John Reed and Dorothy Day.

Distribution of The Masses was barred in the New York subway system, by United News Co. of Philadelphia, Magazine Distributing Co. of Boston, in university libraries, bookshops and by the Canadian postal system. Then the Associated Press sued the magazine in 1913 because it critiqued AP’s reporting of the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912 in West Virginia, a suit that was eventually dropped.

In 1917, The Masses was charged under the Espionage Act with “unlawfully and willfully” obstructing the recruiting and enlistment of U.S. soldiers to fight in World War I, which the magazine opposed. Louis Untermeyer, a writer for the magazine, said, “As the trial went on it was evident that the indictment was a legal subterfuge and that what was really on trial was the issue of a free press.”

The judge instructed the jury: “I do not have to remind you that every man has the right to have such economic, philosophic or religious opinions as seem to him best, whether they be socialist, anarchistic or atheistic.” The first trial ended in a mistrial when one juror was discovered to be a socialist and the other jurors demanded the prosecutors indict him too. The second trial also ended in a mistrial.

The Sedition Act was repealed by Congress in March 1921 and Debs’ sentence was commuted by President Warren Harding.

Tomorrow: In Hot & Cold War

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

If only the information needed could have stopped the slaughter. Usually, not. Even so, everyone assigned to fight or to the fight should have full information as to why, and full autonomy to be part of the killing or not.

I had also been collecting the Mike Gravel articles, putting them in my own Word doc. So, this article got me re-reading that text. I was in the Air Force from 1968 to 1972, having bought into a lot, including Gulf of Tonkin. As I was reading I realized we almost never read or see a comparison of death numbers. We are handed the 58,200 (give or take) as our noble sacrifice. I get health care at the VA. I also fend off any “thank you for your (you-know-what).” Irritating.

But I looked up numbers. Most from the Encyclopedia Britannica (I also use wiki but am careful because CIA, NSA, Mossad, and similar “contributors” are constantly editing the thing to adhere to the party line, as we used to say).

Short takeaway: In terms of percentage of population, the Vietnamese were hit 270 times worse than the US.

Starting with 1970 populations:

Vietnam 43.4 million

United States 205.1

That is 4.726 times larger than Vietnam, getting us the relative population factor

from Vietnamese 1995 release of numbers

2,000,000 V civilians both sides

1,100,000 NVA and Viet Cong

add in the 200,000 to 250,000 estimated South Vietnamese soldiers who died

Using 225,000 as a back-of-the-envelope interpolation

Making 1,325,000 Vietnamese soldiers/fighters on both sides killed

3,325,000 Vietnamese killed x 4.726 (to get the US equivalent)

== US equivalent:

Or the same as if 15,713,950 US soldiers and civilians had been killed in the war

rather than the actual figure of 58,200. Among the reasons we hold fast to amnesia.

Those secrecy laws not only keep those in the US out of the decision loop, but ignore completely the massive numbers of people elsewhere we are killing.

Secrecy is the real crime.