It’s an extreme example of the privileging of profits over lives, writes Jayati Ghosh.

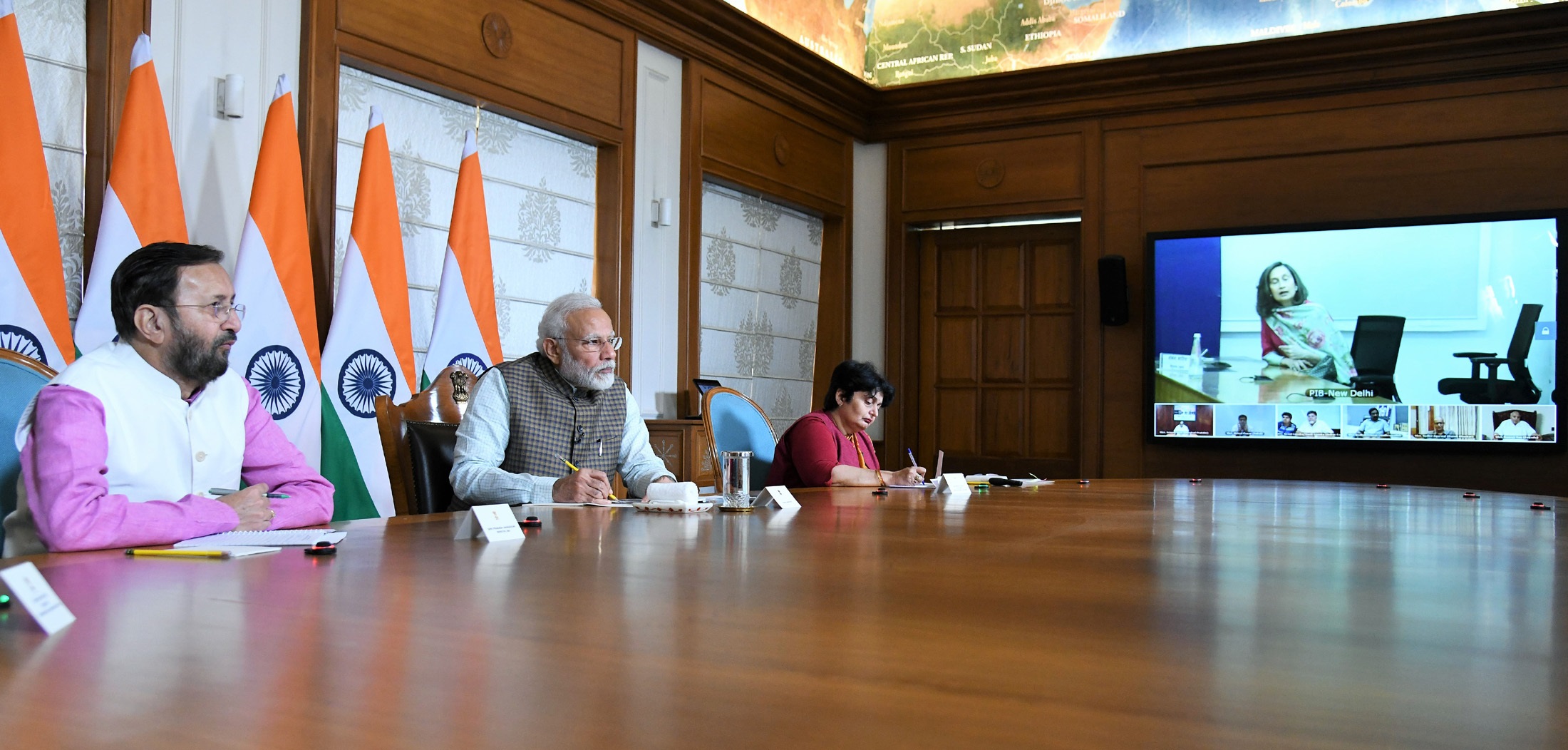

March 24, 2020: India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, second from left, in a video press conference on Covid-19. (Government of India, Wikimedia Commons)

By Jayati Ghosh

International Politics and Society

The unfolding pandemic horror in India has many causes. These include the complacency, inaction and irresponsibility of government leaders, even when it was evident for several months that a fresh wave of infections of new mutant variants threatened the population. Continued massive election rallies, many addressed by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, brought large numbers to congested gatherings and lulled many into underplaying the threat of infection.

The unfolding pandemic horror in India has many causes. These include the complacency, inaction and irresponsibility of government leaders, even when it was evident for several months that a fresh wave of infections of new mutant variants threatened the population. Continued massive election rallies, many addressed by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, brought large numbers to congested gatherings and lulled many into underplaying the threat of infection.

The incomprehensible decision to allow a major Hindu religious festival — the Mahakumbh Mela, held every 12 years — to be brought forward by a full year, on the advice of some astrologers, brought millions from across India to one small area along the Ganges River and contributed to ‘super-spreading’ the disease.

The exponential explosion of Covid-19 cases — and it is likely much worse than officially reported, because of inadequate testing and undercounting of cases and deaths — has revealed not just official hubris and incompetence but lack of planning and major deficiencies in the public health system. The shortage of medical oxygen, for instance, has effectively become a proximate cause of death for many patients.

Failing Vaccination Program

But one significant — and entirely avoidable — reason for the catastrophe is the failing vaccination programme. Even given the global constraints posed by rich-country vaccine-grabbing and the limits on domestic production set by the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement, this is unnecessary and unexpected.

India is home to the largest vaccine producer in the world and has several other companies capable of producing vaccines. Before the pandemic, 60 per cent of the vaccines used in the developing world for child immunisation were manufactured in India.

The country has a long tradition of successful vaccination campaigns, against polio and tuberculosis for infants and a range of other diseases. The available infrastructure for inoculation, urban and rural, could have been quickly mobilised.

In January, the government approved two candidates for domestic use: the Covishield (Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccine, produced in India by the Serum Institute of India, and Covaxin, produced by Bharat Biotech under a manufacturing licence from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) — other producers could have been similarly licenced to enhance supply.

The vaccination program officially started on Jan. 16 , with the initial target of covering 30 million healthcare and frontline workers by the end of March and 250 million people by July. By April 17 , however, only 37 percent of frontline workers had received both doses (of either vaccine); an additional 30 percent had received only the first.

Low uptake even among this vulnerable group could have resulted from concerns about the rapid regulatory approval granted to Covaxin, which had not completed Phase III trials. The Indian government also encouraged exports, partly to fulfil commitments by the Serum Institute of India to AstraZeneca and the global COVAX facility — partly to enhance its own standing among developing countries.

South Africa’s first consignment of Covid-19 vaccine arriving from the Serum Institute of India at the Oliver Reginald Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg on Feb. 1. (GovernmentZA, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

But very quickly thereafter, as vaccinations were extended to the over-60s and then those over 45, the shortage was felt and the pace slowed accordingly. By April 24, only 8.5 per cent of the population had received even one dose — nowhere near what would be required to contain the spread. Even this limited coverage reflected the fact that private facilities had been allowed to administer the vaccine, at a charge of 250 rupees, around €2.76 (or $3.33) per dose.

Modi’s Unrealistic Plan

The Modi government had obviously made the unrealistic call that that existing domestic production of vaccines would be adequate. In fact, it would have taken the two producers on their own three years to meet the required demand. While the ban on exports of some essential ingredients by the Unites States is affecting production of the AstraZeneca vaccine, Bharat Biotech is constrained by its own finite capacity.

Shockingly, the government did not issue compulsory licences to other producers to increase supply, even though Covaxin had been developed by the public ICMR. It had also allowed several public-sector manufacturing units to languish without adequate investment.

Only on April 16, after the pandemic had reached crisis proportions across India and showed no signs of abatement, did the central government finally move to allow three public enterprises to make the vaccine — though three other public-run units, with greater expertise and capacity, were inexplicably left out. Even these new units will now need several months to gear up for production.

In the interim, in a uniquely cynical strategy, the Modi government has passed the buck on vaccination to the states, without providing any funding — indeed making them pay higher prices. It has agreed with the private producers a pricing system whereby state governments already desperately short of finances and facing hard budget constraints will have to pay up to four times what the central government pays for the same vaccines. They are now also being allowed to import vaccines from abroad — they will have to bid on their own for that. To create such a Hunger Games among state governments, without central funding and procurement of vaccines for every resident, can only have disastrous outcomes.

Disaster Capitalism

The latest sign of this active encouragement of disaster capitalism by the Indian state is even more egregious. In the proposed opening up of vaccination to the 18-45 age group from May 1, access is to be limited to private hospitals and clinics, and only on payment — with prices ranging from 1,200 rupees to 2,400 rupees (€13.25-€26.5) per dose! Obviously, the poor will be unable to afford the vaccines, and so the pandemic will rage on, the massive human suffering will continue and countless lives will be lost.

If a novel had been written along these lines, it would be dismissed as too unrealistic and improbable to be taken seriously. Unfortunately, it is only too true — and the strategy of the Indian government is just an extreme example of the privileging of corporate profits over human lives which marks our still-neoliberal world.

Jayati Ghosh is professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi and a member of the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation.

This article is from IPS-Journal and is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our

Spring Fund Drive!

Show Comments