Princess Reema bint Bandar, Saudi ambassador to the U.S., in February 2020. (Dom.Ross, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Ben Freeman, Brian Steiner and Leila Riazi

TomDispatch.com

Princess Reema bint Bandar Al-Saud, Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the U.S., was on the hot seat. In early March 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic swept the world, oil prices collapsed and a price war broke out between Saudi Arabia and Russia, leaving American oil and gas companies feeling the pain. As oil prices plummeted, Republican senators from oil-producing states turned their ire directly on Saudi Arabia. Forget that civil war in Yemen — what about fossil-fuel profits here at home?

To address their concerns, Ambassador Bandar Al-Saud agreed to speak with a group of them in a March 18 conference call — and found herself instantly in the firing line, as senator after senator berated her for the kingdom’s role in slashing global oil prices. “Texas is mad,” Senator Ted Cruz bluntly stated. As the ambassador tried to respond, Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan retorted, “With all due respect, I don’t want to hear any talking points from you until you hear from all [of us], I think there’s 11 or 12 on the call.”

The Saudi lobby in Washington was similarly flailing in its reaction to the anger on Capitol Hill. Hogan Lovells, one of the kingdom’s top lobbying firms in the nation’s capital, was spearheading the response, emailing staffers in the offices of more than 30 members of Congress. Its message couldn’t have been clearer: “Saudi Arabia has not, and will not, seek to intentionally damage U.S. shale oil producers.”

However, its efforts were apparently falling on deaf ears, as some of Washington’s most-lobbied policymakers remained furious at Riyadh for slashing oil prices. Even after being personally phoned four times by Hogan Lovells lobbyists between March and April, according to a Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) filing made by the firm, Senator Sullivan called for the Trump administration to place tariffs on Saudi oil imports. Other Republican senators, who had previously supported billions of dollars in arms sales to the kingdom, now threatened to upend the entire American alliance with Saudi Arabia. North Dakota Senator Kevin Cramer, for instance, warned that the kingdom’s “next steps will determine whether our strategic partnership is salvageable.”

That spring oil dispute was far from the first setback the Saudi lobby had faced in Washington in recent years. From the disastrous Saudi war in Yemen to the brutal murder and dismemberment of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Congress had ample reason to turn its back on that country.

Perhaps not so surprisingly, then, in a series of bipartisan bills that passed the House and the Senate, Congress sought to end America’s military involvement in the Saudi-led coalition’s brutal war in Yemen and halt arms sales to the kingdom. Fortunately for the Saudi lobby, it had President Donald Trump, long wooed by the kingdom’s royals in the most personal of ways, as a safety net to veto those bills and protect them from punishment for their many misdeeds.

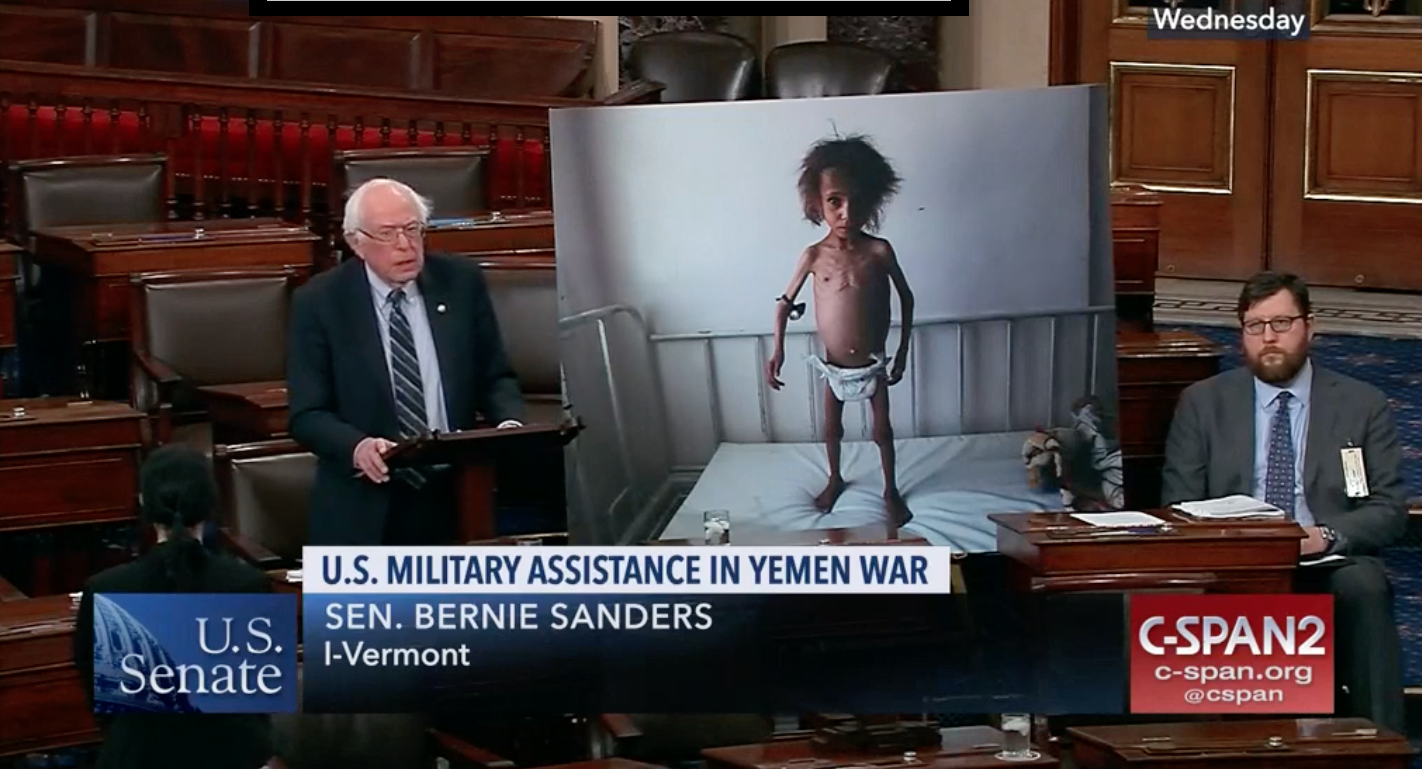

Dec. 12, 2018: U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders denouncing the war in Yemen as a “humanitarian and strategic disaster.” (Screenshot)

Yet, in 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic ravaged America, it became increasingly clear that Trump’s reelection prospects were dimming and, with them, that guarantee of eternal protection.

And so, the question arose: What was an authoritarian government with oodles of lobbying money but dwindling influence in Washington to do as the prospect of a Joe Biden presidency and a Democratic Congress rose? The answer, it turned out, was to move its influence operation from the Beltway to the heartland.

The Saudis Shift to the States

Since becoming ambassador in February 2019, Princess Bandar Al-Saud found herself spending ever more time with people outside the Beltway, particularly in states that were reputed to have deep ties to Saudi Arabia. From Maine to Iowa to Alaska, the Saudi ambassador began a campaign of courting Main Street America.

In July 2020, she spoke at a virtual event hosted by the Greater Des Moines Partnership, the Des Moines International Trade Council, and the Iowa Economic Development Authority. In attendance were many prominent local business leaders such as Craig Hill of the Iowa Farm Bureau and Jay Byers, CEO of the Greater Des Moines Partnership. The event also included some modest star-power, featuring a speech by Hall Delano Roosevelt, the grandson of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the CEO of the U.S.-Saudi Business Council. (He would soon after publish an op-ed in a Maine newspaper urging local lobstermen to build ties with the Kingdom.)

Not surprisingly, the main focus of Ambassador Bandar Al-Saud’s speech was “the importance of the 75-year relationship between Saudi Arabia and the United States.” She also highlighted major changes she claimed were underway in Saudi Arabia, thanks to that country’s “Vision 2030,” a plan sponsored by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, also known as MBS, the son of King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and the power behind the throne there. At least in theory, Vision 2030 was aimed at modernizing and diversifying Saudi Arabia’s oil-based economy.

March 14, 2017: President Donald Trump and Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, or MBS, meeting in Washington. (White House, Shealah Craighead)

Such presentations by the ambassador would soon become a pattern. She would, for instance, make a similar argument later in 2020 to Iowa’s Siouxland Chamber of Commerce’s Women Mentoring and Networking Committee.

And it wasn’t just Iowa. She began giving similar speeches across the country. In July, she spoke at a virtual event hosted by the Maine World Affairs Council. It would be attended by more than 70 members of the Maine business community and former Democratic Congressman Mike Michaud. In early October, again virtually, she addressed the Wyoming Global Technology Summit and more than 80 business and political leaders. They included Governor Mark Gordon (whom she even gifted with two pieces of art) and Cynthia Lummis, who, the next month, would be elected to the Senate. Later in October, the princess would speak to more than 50 local business leaders at the Alaska World Affairs Council.

Bandar Al-Saud’s road show would only sweep on, right past the election and inauguration of President Joe Biden. In late January, she would be at the World Affairs Council in Dallas/Fort Worth and, in March, the Houston World Affairs Council. As always, attending would be business leaders from the area, including (you won’t be surprised to learn) prominent oil executives. Whatever local issues she might focus on in such talks, the ambassador always kept the main focus on the splendors of MBS’s Vision 2030 plan and just how important it was to strengthen the decades-long relationship between the two countries.

Oh yes, and each of these events had one other thing in common: they were all organized and promoted by Saudi Arabia’s registered foreign agents.

Despite appearances, such events weren’t the product of meticulous planning by Saudi diplomats or Bandar Al-Saud herself. Instead, the Saudis have done what many foreign governments do here to make their message heard. They hired lobbyists and public relations firms. In this case, one firm has largely been responsible for the way the Saudis have gotten the word out so far beyond the Beltway: the Larson Shannahan Slifka Group.

Today marks the first day of the 2021 Iowa Legislative session! We wish our government affairs team the best of luck on another successful year!#GovernmentAffairs #Iowa #LS2group pic.twitter.com/J6VF63dtIw

— LS2group (@LS2group) January 11, 2021

Also known as LS2, Larson Shannahan Slifka describes itself as a “bipartisan public relations, government affairs, public affairs, and marketing firm headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa.”

It boasts an impressive collection of clients, including Walmart and the Ford Motor Company. Absent from its website, however, is any hint of the extraordinary amount of work it’s done to boost the Saudis nationally since signing a contract with the kingdom in November 2019 worth $126,500 a month. In its FARA filings, that firm has reported conducting more than 1,600 political activities on behalf of the Saudis — more, that is, than all the other firms working for the Saudis combined in 2020, according to a soon-to-be-released report on the Saudi lobby from the Foreign Influence Transparency Initiative at the Center for International Policy, where we work.

Add in one more factor: unlike other firms that lobby for Saudi Arabia, LS2’s work has taken place almost exclusively outside of Washington, D.C. They’ve reached a remarkably sweeping set of state and local influencers on behalf of the Saudi royals, including small businesses, local politicians, nonprofit companies, small-town media outlets, synagogues, and even high-school students.

And whether any of those Americans realized it or not, they were being swept up in a campaign to give the Saudis local clout nationally and so pave the way for a Saudi public relations rehabilitation campaign in Washington, D.C., itself.

Creating Grassroots for a Gulf Monarchy

There’s a fairly simple pattern to the way the Saudi lobby has been wooing the states to woo Washington. First, Larson Shannahan Slifka launches a local campaign, including hundreds of calls and emails to state legislators, chambers of commerce, university professors, small businesses, and just about anything or anyone you can imagine in between. Some of those ties, in turn, create opportunities for influential media moments such as, for example, when Saudi embassy spokesman Fahad Nazer — a former FARA-registered Saudi agent — conducted interviews with South Dakota Public Radio last October and Michigan’s Big Show this February.

Other lobbying activities have led to crucial Saudi outreach events, filling the seats (or Zoom invites) at think-tank discussions, business forums, or even interfaith dialogues. For example, when Bandar Al-Saud delivered a keynote “fireside chat” at the annual Wyoming Global Technology Summit, John Temte, who leads the business network that hosts the forum, introduced the princess and moderated the question-and-answer discussion, a role likely arranged in the course of LS2’s six calls and emails to him over the preceding two weeks. Five days later, addressing the Siouxland Chamber of Commerce’s Women Mentoring and Networking Committee, the ambassador was introduced by Linda Kalin, the director of the Iowa Poison Control center, and another frequent LS2 contact. In this way, the firm effectively continues to turn local entrepreneurs and public-health officials into community ambassadors for the kingdom.

And understand this as well: such events aren’t just a way for Saudi bureaucrats to meet local business leaders. They also provide the perfect opportunity for Saudi-backed lobbyists to begin rebuilding ties in Washington hurt by those falling oil prices, the devastating civil war in Yemen, and the killing of Jamal Khashoggi. Consider this the second part of the kingdom’s faux-grassroots campaign and, for this, one of the Saudis’ key lobbying groups in Washington, Hogan Lovells, took over.

K Street NW in Downtown, Washington, D.C. groups. (AgnosticPreachersKid, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Its relationship with Saudi Arabia can be traced back at least to 1976 when the firm’s predecessor, Hogan and Hartson, first signed a contract with the kingdom. Now, in addition to spinning a Saudi narrative about the disastrous war in Yemen, that firm has been working to convert LS2’s state and local efforts into political capital in Congress. Armed with glowing one-page summaries of such dialogues from Maine to Alaska, the firm has been promoting a vision of grassroots American support for the U.S.-Saudi relationship inside the Beltway. The event descriptions it sends around highlight many of the same people that Larson Shannahan Slifka had first contacted.

Its emails are tailored to each congressional office it contacts, mentioning issues and local stakeholders relevant to the intended senators and House members. For example, an email to the staff of Republican Senator Susan Collins of Maine touted Bandar Al-Saud’s July forum at that state’s World Affairs Council, described the ambassador’s interest in a Saudi contemporary art exhibit displayed by local Bates College, and noted that former Democratic Congressman Mike Michaud attended the event. This February, after Bandar Al-Saud addressed the World Affairs Council of Greater Houston, Hogan Lovells emailed Republican Senator John Cornyn’s office to underscore her remarks on U.S.-Saudi cooperation on energy, technology, and space exploration in his home state.

While describing audiences in such local forums as responding with “overwhelmingly positive feedback” to the kingdom’s messaging, one key fact is always omitted: that the events themselves were orchestrated by the Saudi lobby. Reading the glossy accounts of them, members of Congress and their staff normally have no idea that the meetings — and not just the press releases they’re receiving — were products of that very lobby. In other words, by omitting such details, the Saudi lobby has effectively launched an astroturfing campaign to influence Congress when it comes to future relations with the kingdom.

The Consequences

Of course, there’s nothing new about such lobbyists hired by foreign countries touting trade with the U.S. or anything necessarily unethical about promoting such ties. However, even as the Saudi lobby has eagerly peddled a rose-tinted story of the kingdom’s increasingly diversified economy, expanding women’s rights, and exciting tourism opportunities (despite the pandemic moment), policymakers and the media that cover them should remember that such a narrative is, at the very least (and to put the matter as politely as possible), incomplete.

While, in the context of Prince Salman’s Vision 2030 plan, selling future economic opportunities to Iowa farmers, South Dakota manufacturers, and Maine lobstermen, LS2, Hogan Lovells, and other such firms ignore the most crucial aspects of the U.S-Saudi relationship in the present moment: the staggering levels of U.S. arms sales to the Kingdom, the devastating war in Yemen that Prince Salman and crew continue to fight, the targeting of Saudi dissidents and women’s rights groups, and MBS’ complicity in the brutal murder of Khashoggi (as laid out recently in an intelligence report released by the Biden administration). These are real-world consequences of a partnership that has often escaped serious scrutiny, shielded by past presidents of both parties more concerned with protecting access to cheap oil and combating their definition of terrorism.

By enlisting trusted community members across the U.S. to help peddle the best possible version of the kingdom, the Saudi lobby has given its brand a homegrown, American-as-apple-pie shine. At a moment when the Biden administration and Congress are weighing the future of the U.S.-Saudi partnership, the value of such an image shouldn’t be underestimated. As lawmakers look more skeptically at claims that American and Saudi security interests are still aligned, the Saudi lobby promises shared future profits in factsheets and emails that hail the historic trade ties between Michigan and Saudi Arabia or characterize the kingdom as “South Dakota’s fastest growing export partner.”

In reality, however, even if a promised future economic boom between the two countries were to materialize, it would hardly ameliorate the kingdom’s many negatives, from the catastrophic famine it continues to stoke in Yemen to its blatant human rights violations. Members of Congress and local public servants alike should beware. What may seem like a spreading grassroots show of support for the kingdom could, in fact, be just another mirage in the desert.

Ben Freeman is the director of the Foreign Influence Transparency Initiative at the Center for International Policy (CIP) and author of a report on the Saudi lobby that will be released in early May 2021.

Brian Steiner is a researcher with the Foreign Influence Transparency Initiative (FITI) at the Center for International Policy.

Leila Riazi is a researcher with the Foreign Influence Transparency Initiative (FITI) at the Center for International Policy.

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support Our Spring Fund Drive!

Show Comments