French President Emmanuel Macron in 2020. (Screen shot)

By Bruno Amable

International Politics and Society

After the brutal murder of the teacher Samuel Paty last year, the compatibility of Islam with the values of French democracy is still widely discussed in the country these days. Recently, the debate has taken a new turn: it now centers around the supposed existence of what was formerly a fringe, far-right idea: the so-called “Islamo-gauchisme,” an alleged alliance between leftists and Islamists among academics and students at French universities representing a threat to the French Republic.

After the brutal murder of the teacher Samuel Paty last year, the compatibility of Islam with the values of French democracy is still widely discussed in the country these days. Recently, the debate has taken a new turn: it now centers around the supposed existence of what was formerly a fringe, far-right idea: the so-called “Islamo-gauchisme,” an alleged alliance between leftists and Islamists among academics and students at French universities representing a threat to the French Republic.

The concept entered the mainstream after French President Emmanuel Macron, his party and ministers adopted it — and used it to propose sweeping changes to civil liberties in a so-called anti-separatism law. Macron’s reaction is not at all surprising. It should be obvious to anyone now that the French president’s political project is a right-wing, neoliberal one. And with the polls narrowing between him and Marine Le Pen in a potential run-off in the 2022 presidential election, Macron’s strategy relies on winning over the right-wing social base that would support his project.

In contrast, Macron’s victory in 2017 was widely perceived as overcoming the left-right cleavage that had traditionally structured political competition in France since the beginning of the Fifth Republic. Presenting his political project as both left and right, Macron had been able to gather some electoral support from the Socialist Party (PS) electorate as well as a fraction of conservative voters.

Gathering at the Place de la République, in Belfort, France, paying tribute to Samuel Paty, Oct. 16, 2020. (Thomas Bresson, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The run-off with Marine Le Pen seemed to indicate the emergence of a new divide between ‘populists’ and progressives. Macron’s political project was to unite the better-off and educated social groups on the Left and Right into a new social bloc that Stefano Palombarini and I have called the bourgeois bloc.

Expanding the Bourgeois Bloc

Macron promised a program of neoliberal “structural reforms,” supposedly boosting growth and alleviating unemployment, while advancing European integration. At the same time, Macron held a progressive discourse on individual rights and societal values. Benefitting from the rupture of the traditional left and right social blocs, Maron succeeded in aggregating the bourgeois bloc and won the presidential and legislative elections.

But the bourgeois bloc is just a small part of the electorate. Its core – the upper and upper-middle classes – has been expanded to the broader middle class thanks to economic (growth through structural reforms) as well as societal promises. But the structural reforms – the implementation of a series of measures that would radically transform the French socioeconomic model – is Macron’s real objective. In order for it to succeed, he needs to broaden his social base beyond the bourgeois bloc. And the only groups likely to support Macron and his neoliberal reform program belong to the former right-wing bloc, as they don’t care so much about his vague promises regarding liberal social values.

Besides, Macron’s neoliberal reform program – concerning labour law, unemployment benefits, pensions, privatizations and so on – is rather drastic and has important consequences for income and status inequalities. This has led to a substantial social opposition: in November 2018, the Gilets jaune smovement rose up and has kept on protesting to this date (albeit in a more discreet fashion).

Protesters in Paris flee tear gas, Dec. 8, 2018. (O.Ortelpa on Flickr)

Considering Macron’s rather narrow social base, such protests could only be dealt with through a rather brutal police repression and by restricting civil liberties. Macron can therefore no longer be considered neither left nor right. Both in terms of economic policies and societal values, his program is, by necessity, firmly anchored on the right because this is where the social base for his reform program lies.

These developments put an end to the fiction of a new divide between populists and progressives. Nevertheless, Macron cannot position himself as the new leader of the right and rely solely on the support of their traditional social base. One reason is the existence of a political competition on the right. Conservative parties such as Les Républicains (LR) have been negatively affected by the rise of Macron, but they have not yet collapsed. Besides, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN), which has a solid electoral base, is also making moves towards conservative respectability. Moreover, a fraction of the traditional right-wing social base belong to the popular classes, which still value the French social model and have no strong inclination towards Macron’s neoliberal reform programme.

Macron’s Strategy for 2022

So Macron is attempting to aggregate a renewed right-wing bloc with a two-pronged strategy. Firstly, the pursuit of the neoliberal structural reforms is likely to alienate a small part of the left-wing middle classes that had joined the bourgeois bloc in 2017. More importantly, however, it is bound to win over the traditional upper and middle classes that had previously backed the traditional conservative parties in the hope of a Thatcherian transformation of the French model. When one compares the reforms made by Macron (and Hollande) to what the right-wing governments have done in the past four decades, it is more than obvious that Macron has been and will be far more neoliberal than any of these governments.

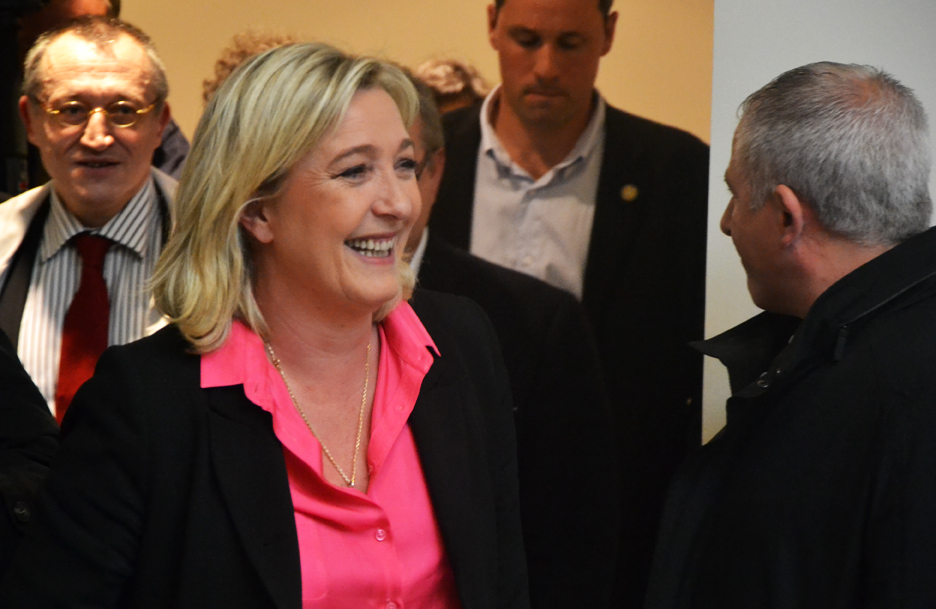

Marine le Pen. (Rémi Noyon via Wikimedia Commons)

Secondly, Macron’s and his party’s promotion of various identity-based societal issues in the public debate – such as the so-called Islamo-gauchisme – is instrumental in the consolidation on the right of the bourgeois bloc. It contributes to blurring the lines between “government parties” such as LREM or LR and Le Pen’s RN, and defining a political space firmly located on the right.

The promotion of identity issues in the media helps to conceal the most controversial aspects of the economic reform program, and thus defuse social opposition. The danger is, however, that this strategy legitimizes Le Pen and makes Macron compete with her for a similar electorate. Macron seems to believe that Le Pen’s incompetence will prevent her from winning the presidential election in 2022. However, this is all but guaranteed. Recent polls show head-to-head race between Le Pen and Macron in the first round, while some show Macron inching to victory in the second round by a mere 4 percent margin.

What Can the Left Do?

Does this situation leave space for a left-wing initiative? The emergence of the bourgeois bloc has probably ruptured the traditional left bloc for good, and has lost them part of the skilled middle classes. A left political strategy can only try to aggregate a renewed social bloc with a political program that differs rather drastically from what the PS has put forward until 2017.

A political debate hinging on concrete material issues – and a political party able to propose a programmatic alternative to the pursuit of neoliberal reforms – could aim to aggregate a revitalized left-wing bloc.

That’s why the Left would benefit from refocusing the public debate on economic structural issues (the neoliberal transformation of the French socio-economic model) and away from identity, race, or religious issues. There is, after all, a social majority in favor of the institutions that Macron’s program aims to dismantle: public education, social protection and public healthcare.

Bruno Amable is professor of political economy at the University of Geneva, on leave from the University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. He is co-author, with Stefano Palombarini, of The Last Neoliberal: Macron and the Origins of France’s Political Crisis (Verso, 2021).

This article is from International Politics and Society.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Macron gambit will fail. The only thing this guy manage to achieve are failures. His first political move was a fart in the face of the people that elected him (rising the CSG). Hope may livin’ but not for Macron. The last Mayors elections was a disaster for his party , the before last EU rep elections : also a disaster with Lepen in Front (sorry , it was so easy).

The bourgeois block might have found another horse to bet on for 2022, there are some weak signals here and there and the last Melenchon advice to beware “a green François Hollande” put the last nail in my conviction’s coffin. Remember Hollande was elected not cause how good he was , but how “normal” in regard of “the exceptional” Sarkozy he was.

Macron and France are making a terrible mistake in rooting tactlessly to the right, to neoliberalism and betting on the bourgoeis bloc.

These same moves would have been rewarding under a better international climate but with Covid induced curfews becoming the norm I am sure the Gilets Jeune and the progressives may gell together and make a boiled nut out of Macron in the electoral showdown.

I wonder how the left wing could reverse the tide with such hostility from the mainstream media. French mainstream media are owned by a few billionaires, who chose Macron before the people voted for him. Same pattern of oligarchy-own media manipulation as the US. Neoliberalism ?…I would call it neo feudalism.

Odd to analyze the situation without once mentioning the collapse brought on by Covid. Voters are sick of the me-or-the-far-right gambit we’ve been been handed too many times and things could reshuffle in any number of ways in the coming year.

Great Article.

I just wonder when another French leader who cares about the French People will show up. Macron sure ain’t that.

~

Out of respect for the French and all their great ideas.

Yours Truly,

Ken

When the 2022 Macron government turn drastically to the right, EU will once again on the brink of collapsing

I like Mariner’s niece, Marion, far better. She might give liberals/leftists nightmares in the future.

“I like Marine[r]’s niece, Marion, far better. She might give liberals/leftists nightmares in the future.”

She got her start on the Le Pen name and then dropped it to gain respectability. She’s got plenty of thissa and thatta, but I suspect a close-up look at her face might chill Willie irremediably.