Many Marxists in colonized zones had never read Marx, writes Vijay Prashad in this sampling of influential leftists, many from peasant societies, who built theories appropriate to their own context.

Book Street in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2016. (Hieucd, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

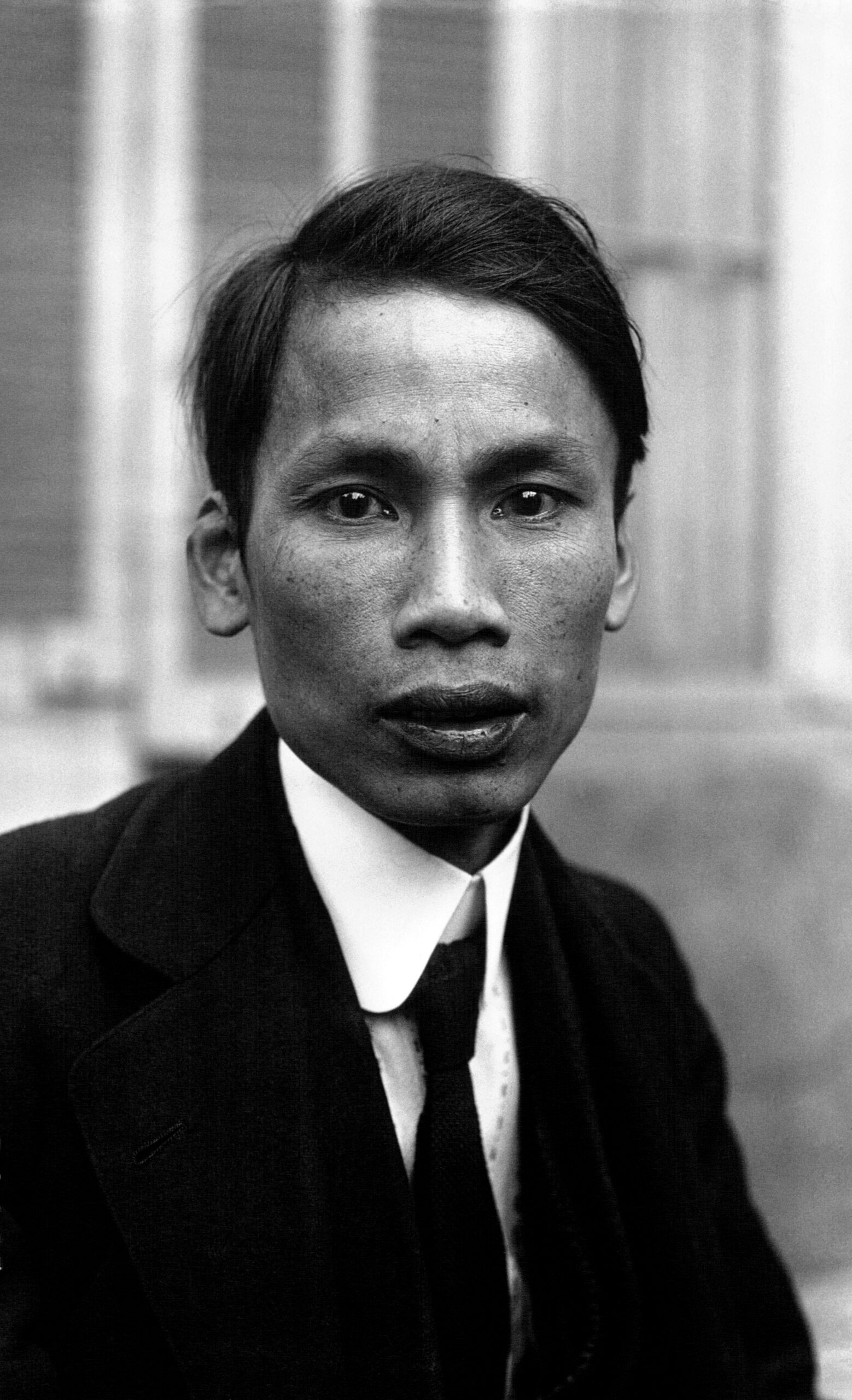

In 1911, a young Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969) arrived in France, which had colonized his homeland of Vietnam. Though he had been raised with a patriotic spirit committed to anti-colonialism, Ho Chi Minh’s temperament did not allow him to retreat into a backward-looking romanticism.

In 1911, a young Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969) arrived in France, which had colonized his homeland of Vietnam. Though he had been raised with a patriotic spirit committed to anti-colonialism, Ho Chi Minh’s temperament did not allow him to retreat into a backward-looking romanticism.

He understood that the people of Vietnam needed to draw from their own history and traditions as well as from the democratic currents set loose by the revolutionary movements around the world.

In France, he became involved in the socialist movement, which taught him about working-class struggles in Europe, although the French socialists could not bring themselves to break with the colonial policies of their country. This frustrated Ho Chi Minh. When the socialist Jean Longuet told him to read Karl Marx’s Capital, Ho Chi Minh found it hard going and later said that he mainly used it as a pillow.

The October Revolution of 1917 that inaugurated the Soviet Republic lifted Ho Chi Minh’s spirit. Not only did the working class and the peasantry take over the state and try to refashion it, but the leadership of the new state offered a strong defense of anti-colonial movements.

With great pleasure, Ho Chi Minh read V. I. Lenin’s “Theses on the National and Colonial Question,” which Lenin had written for the 1920 Communist International meeting. This young Vietnamese radical, whose country had been held in bondage from 1887, found in this text and others the theoretical and practical basis to build his own movement.

Ho Chi Minh went to Moscow, then to China, and eventually returned home to Vietnam to lead his country out of colonial oppression and out of a war imposed on Vietnam by France and the United States (a war that ended with Vietnam’s victory six years after Ho Chi Minh’s death).

Ho Chí Minh in 1921. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons)

In 1929, Ho Chi Minh said that “the class struggle does not manifest itself the way it does in the West.” He did not mean that the gap between the West and the East was cultural; he meant that the struggles in places such as the former Russian Empire and Indo-China had to take into consideration a number of factors unique to these parts of the world: the structure of colonial domination, the deliberately underdeveloped productive forces, the abundance of peasants and landless agricultural workers and the inherited and reproduced wretched hierarchies of the feudal past (such as caste and patriarchy).

Creativity was necessary, which is what made the Marxists in the colonized zones build their theory of struggle out of a concrete engagement with their own complex realities. The texts written by people such as Ho Chi Minh appeared as if they were merely commentaries on the current situation, when in fact these Marxists were building their theories of struggle out of specific contexts that were not immediately apparent to Marx and his main successors within Europe (such as Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein).

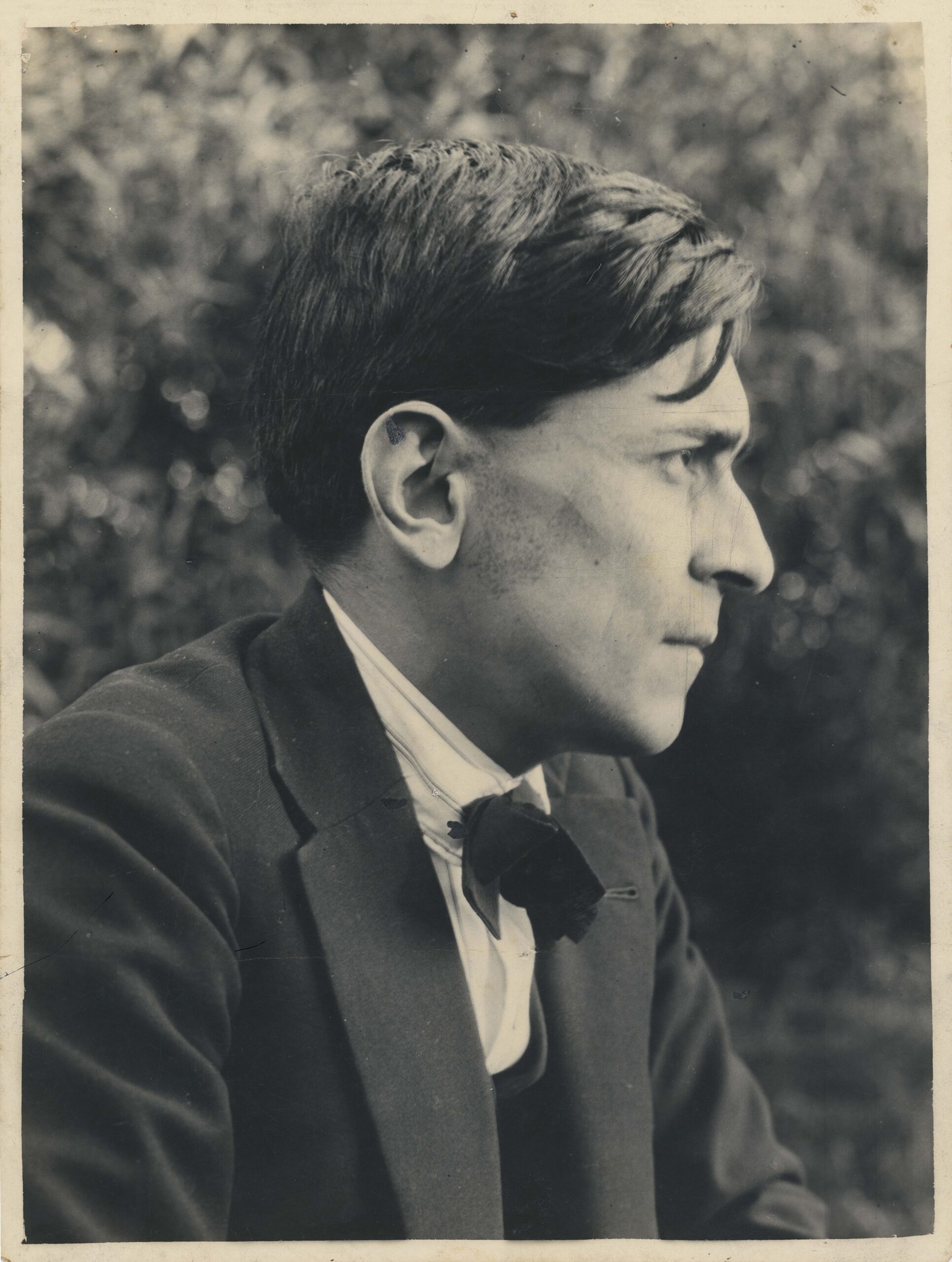

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research dossier no. 37, “Dawn: Marxism and National Liberation,” explores this creative interpretation of Marxism across the Global South, from Peru’s José Carlos Mariátegui to Lebanon’s Mahdi Amel. The dossier is an invitation to a dialogue, a conversation about the entangled tradition of Marxism and national liberation, a tradition that emerges out of the October Revolution of 1917 and that deepens its roots in the anti-colonial conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries.

José Carlos Mariátegui in 1929. (José Malanca, Wikimedia Commons)

When the categories of Marxism drifted outside the boundaries of the North Atlantic region, they had to be “slightly stretched,” as Frantz Fanon wrote in Wretched of the Earth (1963), and the narrative of historical materialism had to be enhanced.

These categories surely had a universal application but could not be applied in the same way everywhere. Each of the movements that took up Marxism — such as the movement to liberate Vietnam led by Ho Chi Minh — had to first translate it into their own context. The central problem of Marxism in the colonies was that the productive forces in these parts of the world had been systematically eroded by imperialism and the older social hierarchies had not been washed away by the currents of democracy. How does one make a revolution in a place without social wealth?

Lenin’s lessons resonated with people like Ho Chi Minh because Lenin argued that imperialism would not allow the development of the productive forces in places such as India and Egypt. These were regions whose role in the global system was to produce raw materials and buy the finished products of Europe’s factories. No liberal elite emerged in these regions of the world that was truly committed to anti-colonialism or to human emancipation.

Creating Basis for Social Equality

In the colonies, it was the left that had to drive the struggle against colonialism and for the social revolution. This meant that it had to create the basis for social equality, including the advancement of the productive forces.

It was the left that had to use the scarce resources that remained after colonial pillage, amplified by the enthusiasm and commitment of the people, to socialize production through the use of machines and better organization of labor and to socialize wealth to advance the development of education, health, nutrition, and culture.

Each of the socialist revolutions after October 1917 took place in the impoverished zones of colonialism, such as Mongolia (1921), Vietnam (1945), China (1949), Cuba (1959), Guinea Bissau and Cabo Verde (1975), and Burkina Faso (1983). These were mainly peasant societies, their capital stolen by their colonial rulers and their productive forces developed only so as to allow for the export of raw materials and the import of finished products. Each revolution was met with immense violence from their departing colonial rulers, who focused on destroying the remaining wealth of the society.

The war against Vietnam is emblematic of this violence. One campaign, Operation Hades, provides a sufficient illustration. From 1961 to 1971, the United States government sprayed 73 million litres of chemical weapons to destroy any vegetation in Vietnam. Agent Orange, the most terrible of chemical weapons in its day, was used on most of Vietnam’s agricultural belt.

U.S. Air Force spraying defoliant next to a road in South Vietnam in 1962. (U.S. Air Force, Wikimedia Commons)

This warfare not only killed the millions who died in the war, but it left socialist Vietnam with a terrible legacy: tens of thousands of Vietnamese children were born with grave challenges (spina bifida, cerebral palsy) and millions of acres of good farmland were made toxic by these weapons. Both the medical and agricultural devastation have lasted for at least five generations, with every indication that they will persist for several generations more.

Vietnam’s socialists had to build their country not out of a textbook model of socialism but by confronting the maladies inflicted upon their country by imperialism. Their socialist path had to run through the terrible reality that was specific to their own history and reality.

Our dossier makes the point that many Marxists in the colonial world had never read Marx. They had read about Marxism in various cheap pamphlets and had encountered Lenin in this form as well: books were too expensive, and they were often difficult to get. People like Cuba’s Carlos Baliño (1848-1926) and South Africa’s Josie Palmer (1903-1979) came from humble backgrounds with little access to the intellectual traditions out of which Marx’s critique emerged. But they knew its essence through their struggles, and through their reading and their own experiences, they built theories that were appropriate for their context.

Today, committed study continues to be a pillar for our movements and for our hopes of building a better future. For this reason, each year, on Feb. 21 February, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research participates in Red Books Day.

Last year, over 60,000 people went into public places to read the Communist Manifesto on the 172nd anniversary of its publication on Feb. 21, 1848.

This year, due to the pandemic, the events will mostly take place online. We encourage you to seek out publishers and organizations in your area that might be holding a Red Books Day event and get involved. If there are no events near you, please hold your own event or take to social media to talk about your favorite red books and what they mean to your struggles. We hope that Red Books Day will become as central to our calendar as May Day.

Ho Chi Minh – whose name means “Well of Light” – was almost always seen with his pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes and a book near at hand. He loved to read and he loved conversation, both of which helped develop his understanding of the world in motion. What red book rests beside you as you read this newsletter? Will you join us on Red Books Day and add our new dossier to your red book reading list?

Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian, journalist and commentator, is the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the chief editor of Left Word Books.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

This is really good and a correct discussion of the role that Marxism played in the major revolutions of the 20th century. Commentators want to transform Marx into the master revolutionary. He was not. His Communist Manifesto was written in support of the impending revolutions of 1848 but the bulk of his work is philosophic, economic, and humanist. Marx is best because he attempts to write humanist philosophy in the era of emerging capitalism and anti-humanist philosophies that emerged with it — utilitarianism, social-darwinism, and fascism.

Marx and communism are best seen as distant ideals for people like Ho Chi Minh but also much better known revolutionaries like Lenin, Castro, and Mao Zedong. Their real problem were local and cultural. While Marx’s understanding of capitalism was brilliant, he did not understand the culture or economy of Asia very well. His ideas about the “Asiatic means of production” are pretty thin. But I guess few people in the west understand Asian economic principles.

Marx’s work is about the West and its social and economic transformations. He’s the best on that.

‘Last year, over 60,000 people went into public places to read the Communist Manifesto on the 172nd anniversary of its publication on Feb. 21, 1848.’

The original Manifesto of 1848 listed some progressive reforms, but ceased advocating them by 1872. The measures – ranging from nationalisation to a heavy progressive or graduated income tax – may have had merit in 1848 but not today. Indeed, Marx and Engels in their joint preface to the 1872 edition stated: ‘No special stress is laid on the revolutionary measures proposed at the end of Section II. That passage would, in many respects, be differently worded today.’ Yet this does not stop our opponents, particularly on the Right, from resurrecting ideas, long dead and buried, to besmirch socialism/communism. The Mises Institute, for example, has used them to suggest that socialism is to blame for the suffering of our class in state capitalist Venezuela. More recently, in an article titled ‘How the Presidential candidates rehash failed communist ideas’ (thedailybell.com, 15 October 2019), Joe Jarvis wrote ‘Marx would fit right in running for President amongst the current crowded field of “democratic socialists” clamoring to one-up each other with the most communist platform. For instance, Bernie Sanders’ platform includes a top estate tax–aka inheritance or death tax–of 77%.’ Later, for good measure, he added the failings of Bolsheviks and state capitalist China to the mix. Pure nonsense of course because, as Rosa Luxemburg said succinctly, ‘without the conscious will and action of the majority of the proletariat, there can be no Socialism.’

Vijay excellent article. I live in the US and it seems to me that the current situation here is in some ways the flip side of the problems faced by the victims of imperialism. The US has evolved to be the most powerful imperial power that has ever existed which seeks what the US military calls “full spectrum dominance”, politically, diplomatically, economically and militarily even to the extent of colonizing segments of its own population while driving the 99% to desperation. We who struggle from within the belly of the beast need a theory of action for a situation the world has never seen before in exactly the same form. I hope there is something coming on this topic from Tricontinental.

While studying in Switzerland Karl Marx’s book ‘ Das Kapital’ was an obligatory studybook!! It certainly widened my economic knowledge!

In all of this, a highly important fact is being ignored: Tsarist Russia was also a backward country mired in feudalism, with 85% of its population composed of peasants, with similar levels of illiteracy. Despite such backwardness, the October Revolution was a workers revolution and not a peasant/guerrilla uprising that overthrew capitalism. None of the latter transformations produced any organs of workers democracy (eg, workers soviets), and despite the involvement of the working class in none of them, the emergent socialised property relations were qualitatively the same as those emanating from October.

With the emasculation of the soviets and the ascent of Stalin and the bureaucracy in a political counterrevolution, the Russian revolution degenerated into a repressive bonapartist regime, without affecting the property relations. That’s what economic backwardness does — if the socialist revolution doesn’t spread to an advanced country then scarcity, compulsion and corruption will flourish, as the revolution materially fails to fulfill its goals and promises. Left isolated, counterrevolution will engulf it eventually, and Lenin and Trotsky feared this from the very outset.

As is acknowledged here, the bourgeoisies of countries kept backward by imperialism, including Tsarist Russia at the time, are too enfeebled to carry out the basic tasks of bourgeois revolutions which can only be performed by overthrowing the corrupt and thin bourgeois-feudalistic layer that imperialism relies upon and which in turn props up. This is the essence of Trotsky’s Permanent Revolution ‘heresy’: in the imperialist epoch only a socialist revolution can carry out the tasks of a bourgeois revolution in backward countries.

When guerrilla uprisings also completely destroyed the state machine propping up the decaying social order, to retain power they were compelled to replace the state. However, unlike the Bolsheviks, none of the guerrilla movements ever at the outset aimed to destroy the bourgeois state or expropriate the capitalists and landowners. At most they aimed to change the regime to a more ‘progressive’ and ‘independent’ one, and reform the state accordingly. For instance, after taking power, Mao Tse Tung repeatedly looked around for a fictitious ‘progressive’ wing of the bourgeoisie to form a coalition government with (they swum to Formosa/Taiwan), and also implored the US to help (to no avail). For a short while Castro held out hopes for a compromise with the US, but was ‘rewarded’ instead with the Bay of Pigs and economic strangulation (the Cuban bourgeoisie swum to Florida). With all hopes and illusions of ‘compromise’ dashed, Mao and Fidel were forced to nationalise their economies and subject them to planning. These subsequent regimes used as their model the Stalinist bureaucratic regime, and in Fidel’s case his ‘Marxist’ verbiage emerged only after receiving aid from the USSR.

A closer look at Uncle Ho’s early history is instructive as to ‘adapting’ Marxism to local conditions. Ho Chi Minh learnt his ‘Marxism’ from Stalin, when he first was involved in the Communist International in 1923, at its Fifth Congress, particularly with Zinoviev’s ‘Peasant International’ (a phantom creation). This was in line with Stalin’s Menshevik policy of the ‘democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry’ (the formulation that Lenin disowned in his famous April Theses [1917]). Ho went first to China in 1925 not to build communist parties but a Vietnamese socialist-oriented nationalist youth grouping (Thanh Nien). This was actually more egregious politically than Stalin commanding the Chinese communists to liquidate into the already-existing nationalist movement of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang. Nonetheless, Ho refused to learn the bloody lesson of the latter, when the Chinese communists were slaughtered by Chiang Kai-shek in April 1927. And he only resorted to building a communist party when part of his organisation’s leadership split away in 1929 to build one.

The Viet Minh (aka NLF), formed in May 1941, was a creation of Ho Chi Min and the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP). Its demands at best were vague about ‘land reform’ and centred on reducing land rent, forced labour and usury. Compare that to the Bolsheviks program for the peasantry of ‘Land to the Tiller’. With the departure of the Japanese in August 1945, the Viet Minh moved to fill the political vacuum. With help from US advisors, Ho drew up its proclamation of independence using phraseology straight out of the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, classic bourgeois revolutionary documents. No mention of ‘socialism’. The Vietnamese emperor (Bao Dai) wasn’t even deposed, let alone beheaded, but appointed ‘Supreme Political Advisor’! In fact, Ho was happy for the French to grant Vietnamese independence in ‘not less than five and not more than ten years’, and signed the 1946 agreement to formally allow French troops back into the country!

Does it get worse? Of course. In southern Vietnam, where the Stalinists were weaker, workers and peasant uprisings occurred immediately after the Japanese surrender. However, the Viet Minh were able to carry out a bloodless coup in Saigon (25 August), simply taking over the existing state machine and forming a bonapartist bourgeois government. The new Stalinist Interior Minister (Nguyen Van Tao) issued the following threat: ‘Whoever encourages the peasants to take over the landed properties will be severely and pitilessly punished…. We have not yet carried out a communist revolution, which would bring a solution to the agrarian problem’. No, this was not an ‘unconscious’ Trotskyist! It was the Viet Minh that positively greeted the return of the allied imperialist forces. Immediately upon arrival in Saigon, British General Gracey immediately proclaimed martial law, banned all Vietnamese press and imposed a strict curfew.

Opposed to both the Viet Minh and the imperialist occupiers was a workers and peasant uprising in the south led by a widespread network of ‘Peoples Committees’ (nascent if classless soviets). It was the Viet Minh who moved to behead it and who had its mainly Trotskyist leadership targetted and shot. Meanwhile, in the north Ho was similarly happily welcoming Chinese and French troops and ordering the complete dissolution of the Indochinese Communist Party into a broader movement to support the allied occupation forces. The Viet Minh proceeded to liquidate the remaining opponents to the occupation and to Viet Minh’s complete capitulation to the imperialists.

Vietnam at the end of WWII had significant working class forces with a chance of carrying out a workers revolution. Instead, armed with the Stalinist ‘theory’ of two-stage revolution, three decades of guerrilla warfare ensued at the cost of 3 million Vietnamese workers’ and peasants’ lives. While the military victory of the Viet Minh was welcome, the effort was needlessly costly.

In short, from his earliest days, Ho Chi Minh ‘adapted’ Marxism to local conditions by appeasing imperialism and the local bourgeoisie and landlords, and by having actual Marxists shot in that appeasement. Similar ‘local conditions’, funnily enough, applied also in China, Spain and elsewhere, with exactly the same ‘adaptation’. Marx and Lenin would indeed have been ‘pleased’ with such ‘adaptations’.

While Vietnam remains a workers state (ie, socialised property, economic planning), as does Cuba, North Korea, China and Laos, to be defended from imperialism and counterrevolution, this side of a political (not social) revolution, real, meaningful workers democracy in all the extant workers’ states remains absent. Under the Stalinists, the many signs of capitalist penetration don’t bode well in Vietnam. As is occurring in China, the lack of workers democracy not only is necessary for Stalinist rule but also eases tremendously the encroachments of capital and, ultimately, capitalist counterrevolution.

Was hoping this might be a critique for why Vietnam has basically descended into Red Capitalism since it kicked out its original Western colonizers. Now their economy is being colonized by developed southeast Asian who like to use it for seedy outsourcing operations.

Important article, I would love to be able to connect with Vijay Prashad.

Very nice. Thank-you. Peace is easy.

~

We all got our little book with us whether we write something into it or not on any given day. We got the book in our heads.

~

Personally, I love sharing stories with others or shooting the bull with those who happen to enter the neighborhood – assuming there is no bad intent. I don’t know about you, but I’m seriously ready to study hard. I want to learn. That is why stories are so much fun. You might think you are telling the story and got something to teach, and that may well be the case, but if it is happening in real time when you are close by another human, then it is a human moment when there are many opportunities for learning together. Learning together is the BEST! Plus, had Lenin not known of Kropotkin, I doubt he would have ever written anything. Funny how history weaves and winds and in my opinion, lately, I’ve been more interested in herstory. Just to get all goofy about it.

~

Thanks and Peace to You,

BK