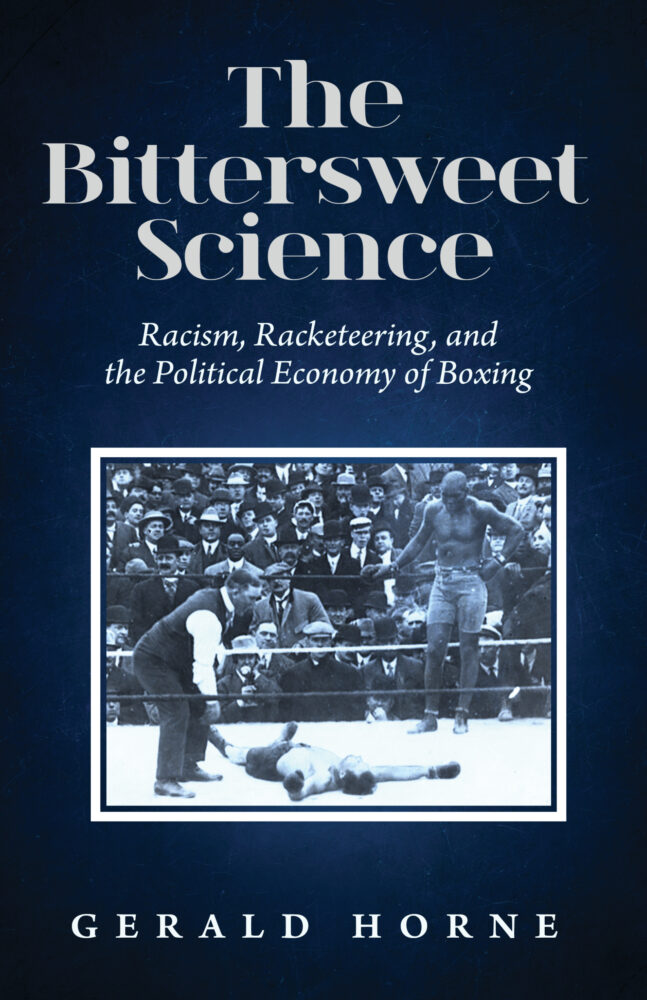

Chris Hedges reviews Gerald Horne’s book, The Bittersweet Science, on racism, racketeering and the political economy of boxing.

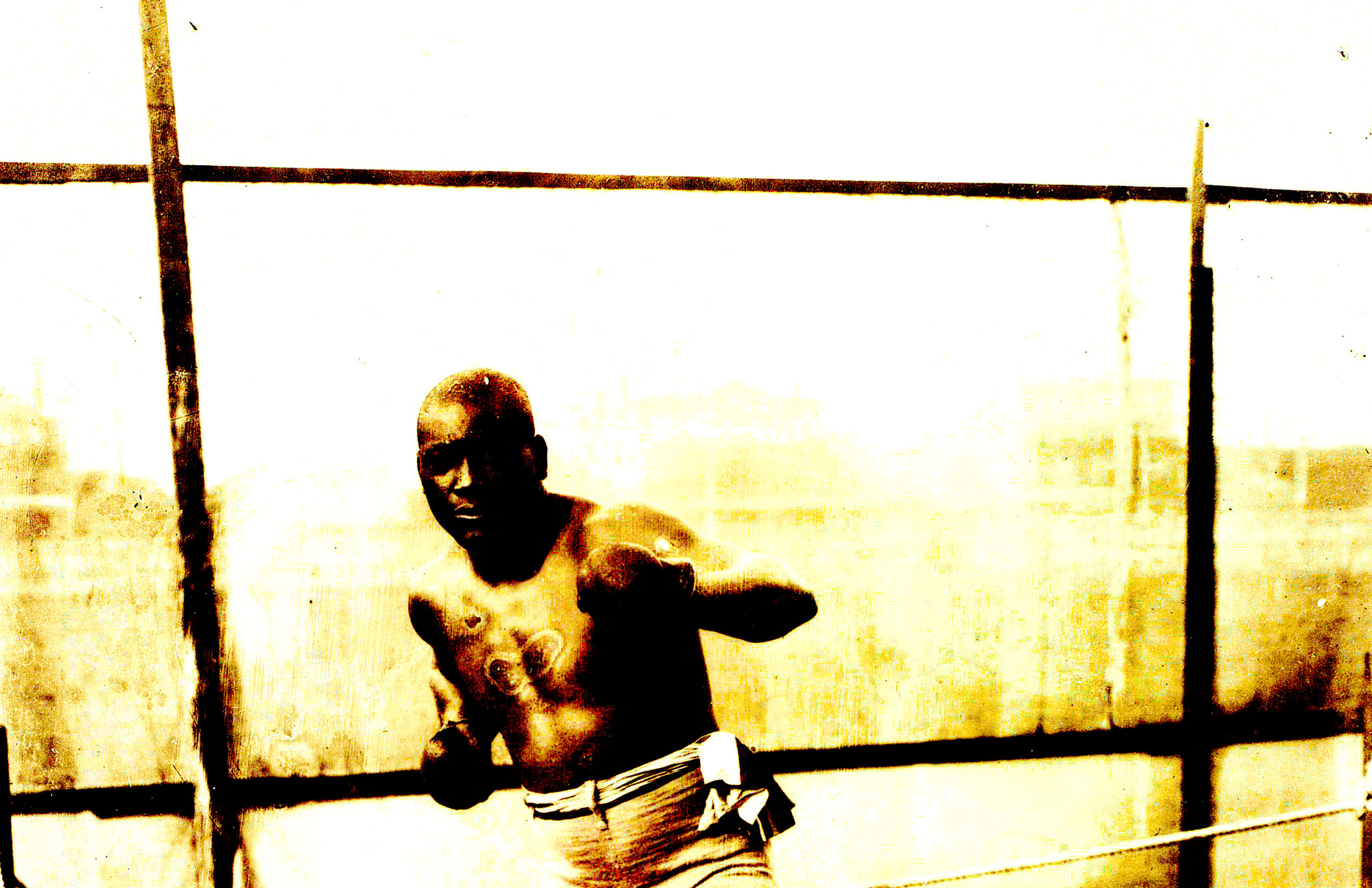

Jack Johnson, African-American boxer and world heavyweight champion, in Sydney, ca. 1908. (Wikimedia Commons)

By Chris Hedges

ScheerPost.com

There were three nationally prominent Black men in the early 20th century. Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute; W. E. B. Du Bois, perhaps America’s most important intellectual; and the world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

There were three nationally prominent Black men in the early 20th century. Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute; W. E. B. Du Bois, perhaps America’s most important intellectual; and the world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

Washington, lavishly funded and feted by the white ruling class, embraced submission. DuBois, Washington’s nemesis, exposed and condemned the economic, political, legal and cultural systems that ensured submission.

And Johnson simply refused to be submissive, dating and marrying white women, flaunting his wealth in tailored suits and fine motor cars, opening an integrated nightclub in Chicago run by his wife, who was white, and pounding Caucasian opponents senseless at a time when striking a white man out of the ring could mean death by lynching.

Boxing, as the historian Gerald Horne argues in his engaging and meticulously researched book, “The Bittersweet Science: Racism, Racketeering, and the Political Economy of Boxing,” was effectively weaponized by Blacks in the battle against white supremacy.

It was vital in demolishing the ugly stereotypes and myths propagated by the white majority about Blacks. Johnson, perhaps the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time, was as eloquent and uncompromising as he was tactically brilliant in the ring.

It was vital in demolishing the ugly stereotypes and myths propagated by the white majority about Blacks. Johnson, perhaps the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time, was as eloquent and uncompromising as he was tactically brilliant in the ring.

And when he could not be defeated, the white ruling class hounded and persecuted him, as they would do decades later with Du Bois, by perverting the law to banish him from the sport and drive him into exile.

Boxing was, as Horne notes, “in many ways the ne plus ultra of capitalism itself, the essence of its unavoidable accoutrements: white supremacy, masculinity, violence, profiteering, corruption.”

Boxing matches were a common diversion for white slaveholders. Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass write of witnessing boxing matches arranged by slaveholders, “not only as entertainment for themselves,” Horne writes, “but also as a way to encourage divisions and rancor among captives.”

Forcing enslaved people to fight, often to the death, is as old as human bondage. It was a custom practiced by the Etruscans at funerary games, a forerunner of Roman gladiatorial contests. SS officers in Auschwitz made Salomo Arouch, the Greek middleweight boxing champion who was of Jewish descent, fight other prisoners two or three times a week for their entertainment. Boxers in Auschwitz that lost were usually sent to the gas chambers or shot. Arouch had some 200 bouts in Auschwitz. He survived because he was undefeated.

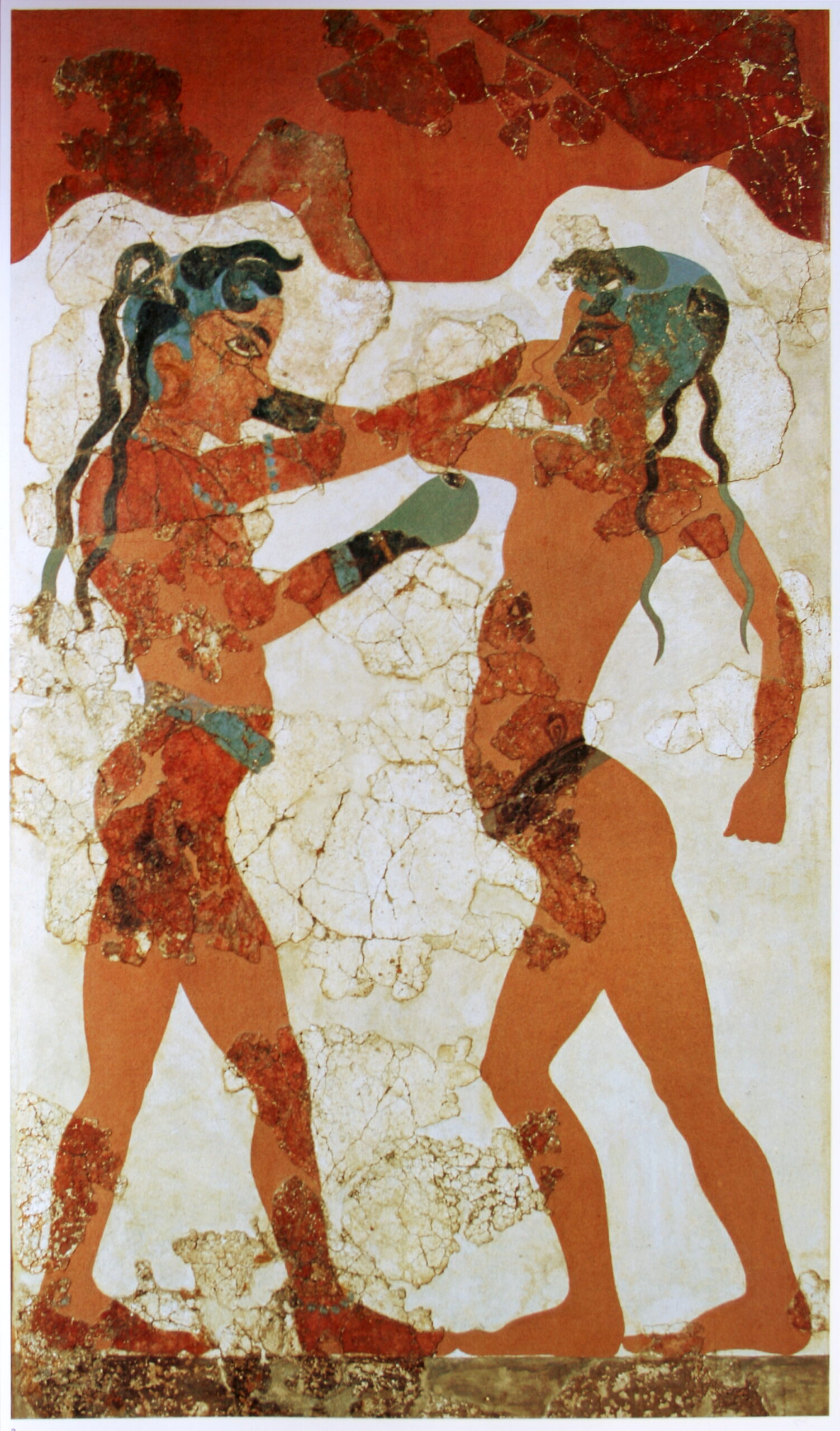

Painting of Minoan youths from a Bronze Age fresco circa 1650 BC shows ancient use of boxing gloves. (Le Musée absolu, Phaidon, Wikimedia Commons)

Following slavery, Black boxers were enticed or coerced into the ring. A popular form of entertainment at fairs and carnivals was the battle royal. As many as a half dozen Black men, stripped to the waist and sometimes blindfolded, were herded into a roped arena on a platform, and made to fight until only one man was standing.

But there was also an established and popular Black boxing circuit. As the skill of Black boxers became undeniable, and white challengers were defeated, whites mounted a crusade to ban interracial prizefighting. “It was feared that Negroes would no longer accept the hocus-pocus of white supremacy as they were busily dismantling boxers of that persuasion in the ring,” Horne writes.

The Los Angles Times noted the explosive nature of Jack Johnson’s victory over James J. Jeffries with this political cartoon suggesting a stick of dynamite would not have caused as much violence. (Wkimedia Commons)

Boxing was and is about gambling. Its popularity has waned in large part because of its brutality — 87 percent of boxers suffer brain damage during their lifetime, and between 1945 and 1985, 370 pugilists died from injuries incurred in the ring. But in the 1950s there were five weekly televised boxing shows. The sight of Black men, as Horne writes, “battering into incoherence those once thought to be the ‘ruling race’” was a potent tool in the battle against Jim and Jane Crow and segregation.

Cesspool of Corruption

The popularity of the sport also made it a cesspool of corruption, drawing into its orbit mobsters, predatory promoters and managers, on-the-take referees and boxing officials along with colorful con artists. Boxers, often fleeced of their purses, as was the heavyweight champion Joe Frazier, or who were unwilling to fix fights to pull off gambling coups, could end up dead.

Horne notes that it was only Muhammad Ali’s ability to mobilize The Fruit of Islam, the muscle organized by The Nation of Islam, which saved him from organized crime.

Mobsters controlled the career of the heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. “Frankie” Carbo, from the Lucchese crime family, took 52 percent of Liston’s earnings; Frank “Blinky” Palermo, a mobster reputed to have fixed the fight between Jake LaMotta and Billy Fox in 1947, took 12 percent, and John Vitale, the boss of the St. Louis crime family, walked away with another 12 percent—leaving Liston “with a pittance after paying training and other expenses,” Horne writes.

Sports writers were also routinely given cuts, including Damon Runyan who had 4 percent interest in the earnings of Joe Louis, the world heavyweight champion from 1937 to 1949.

“It was in 1964 that the heavyweight Sonny Liston, whose loss to Ali catapulted the former ‘Louisville Lip’ into the ionosphere of fame, got into a heated confrontation with Las Vegas’ top mobster, Moe Dalitz (who had roots in [the fight promoter Don] King’s Cleveland), though the scalding words were exchanged at a posh Beverly Hills hideaway,” Horne writes.

“‘If you hit me,’ Dalitz growled menacingly to the barely literate boxer, ‘you’d better kill me, because if you don’t, I’ll make just one telephone call and you’ll be dead in 24 hours.’ Dalitz was no cipher: Former Nevada Governor Grant Sawyer said that the jowly and pugnacious battler ‘was probably as responsible for the successful gaming economy in Southern Nevada as any one person.’ Perhaps predictably, Liston died mysteriously at home a few years later in circumstances that remain opaque. As shall be seen, Liston had questionable ties to various mobsters throughout his star-crossed career. One investigator charges that he agreed to take a ‘dive in his second fight with Ali,’ i.e., agreed to lose beforehand, thereby ‘making [the billionaire developer Kirk] Kerkorian a lot of money,’ who then proceeded to give him a ‘sweet deal’ on his Las Vegas abode.”

“Tellingly,” Horne writes, “perhaps the other sport that challenged boxing’s pre-eminent role as a sink of corruption was a sport where non-humans were paramount: Horse racing. This culture of corruption was facilitated by the fact that boxing was a major sport without a regular schedule, strict regulation on a national scale (facilitating the arbitrage opportunities eased by scores of statewide regulatory bodies), reliable records, objective scoring, etc.,” Horner writes.

“It was a kind of ‘free enterprise’ of deregulation or ‘neoliberalism’ run amok; that is, it was a sport designed with raw capitalism in mind, which in turn lubricated the path for the arrival of gangsters who thrived in such an environment, especially when the bodies to be exploited were disproportionately those of an ebony hue. It was a ‘battle royal’ updated for the 20th century.”

The rise of gifted Black boxers, such as Johnson, gradually put pressure on white promoters to repeal the racial ban and allow Black boxers to fight whites.

Search for Great White Hope

And once boxing was integrated, in large part because of the relentless lobbying by Johnson who hounded and taunted white champions, there was a ceaseless and frantic search for the great white hope. The yearning for a white boxer who could defeat a Black champion, especially a heavyweight, and burnish the myth of white supremacy, would define the reign of all Black heavyweight fighters, including Joe Louis and Mohammed Ali.

Jack Johnson in 1908. (Otto Sarony, Wikimedia Commons)

“Johnson’s stunning defeat of Jeffries in 1910 was more than just a turning point in boxing, which it certainly was,” Horne writes of Johnson’s defense of his world heavyweight title against the undefeated world heavyweight champion James Jeffries, who was white and who was lured out of retirement to fight Johnson.

“It upended musty stereotypes about the alleged ‘yellow streak,’ purported cowardice and supposed ‘softness’ of Negro men, as the dark-skinned Johnson became de facto king of masculinity. It inspired racist attacks — and counterattacks. In the future birthplace of Muhammad Ali, Euro-Americans attacked Negroes for their outward enthusiasm hailing Johnson’s triumph, and in response Negroes struck back with vigor in Louisville. A Carson City periodical captured the tensions of the time as it reported breathlessly on the ‘general movement in most of the large cities to suppress the showing of the fight films,’ meaning the unassailable triumphs on celluloid of Johnson and [Joe] Gans [the World Lightweight Champion from 1902–1908], among others: In ‘many of the big cities, especially in the South, where the Negro population ranks high in numbers, the authorities are putting the ban on the fight pictures fearing that [said images] further swell the chests of the colored men.”

Those trapped in poverty and discriminated against because of their race or religion gravitated to boxing, as was still true when I boxed in Boston in the early 1980s. Boxing was one of the very few tickets out of misery.

Jewish-American boxers in the 1920s were the dominant group in the ring, followed by the Italians and the Irish. The Jewish fighter Benny Leonard, who scored 70 knockouts from his 89 wins, was the world lightweight champion for eight years. Leonard, Lou Halper wrote, “did as much with his fistic prowess to gain respect of the Jews” as “did the Anti-Defamation League.” As these outcast groups integrated into the wider society, something that Blacks have never been fully permitted to do, their representation in boxing diminished.

“It did not require an advanced degree to ascertain that qualities that inhered in adroit boxing — quick thinking, instinctively developing strategy and tactics for victory, tenacity, etc. — were fungible and adaptive to various environments, especially politics,” Horne writes. “This was particularly true of the political culture in the U.S., a nation which was created as a result of violent uprooting of Indigenes and of a pervasive brutality deployed to keep millions of the enslaved in line.”

The descent of boxing, hastened by the public’s awareness of the sport’s near inevitable traumatic brain injuries and the painful public display of Ali’s slurred speech and increasingly limited, shaky movements, saw it replaced with more extreme fight forms, “a kind of free-for-all” with “the ultimate beneficiary being orthopedic surgeons in for-profit hospitals,” as Horne writes.

These extreme fights are little more than organized brawls in cages, staged like the old battle royals for their savagery rather than their art. For great boxers are artists, able to move with the grace and swiftness of dancers, endowed with lightning reflexes and able to nimbly outwit, through superb conditioning, strategy and intelligence, less astute or trained opponents.

But even when boxing was at its height, these intricate and complex athletic skills were of secondary importance to most of those who flocked to boxing arenas, longing to see a man battered and pummeled into an unconscious mass. Those of us who boxed wanted fights stopped as soon as one of our own fighters was dazed, unsteady and unable to protect himself. It was, at that point, for us no longer a sport. But when a fighter was defenseless the crowds, which we loathed, came to life, clamoring for blood, which those who organized the fights were only too willing to deliver.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who was a foreign correspondent for 15 years for The New York Times, where he served as the Middle East bureau chief and Balkan bureau chief for the paper. He previously worked overseas for The Dallas Morning News, The Christian Science Monitor and NPR. He is the host of the Emmy Award-nominated RT America show “On Contact.”

This column is from Scheerpost, for which Chris Hedges writes a regular column twice a month. Click here to sign up for email alerts.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

I for one thoroughly appreciated this article especially the discussion about Jack Johnson, who was a great and courageous man. My wife and I watched a documentary about him several years ago (can’t remember whether it was on the History Channel or maybe Netflix….) – anyhow, it was very enlightening.

~

Personally, I’m opposed to any attempt to “ban boxing”. Everybody just wants to ban everything and I don’t think that is the solution. In fact, I think the author had another article speaking to this to an extent.

~

Lastly, I have seen “an artist” beat someone not only unconscious but beat them to death slowly over time. It was excruciating. Boxing has no monopoly on that and if you get in the ring you should know what to expect.

~

BK

“great boxers are artists”. I’ve yet to see an artist beat someone into unconsciousness. Really, Mr Hedges, whatever the politics – and you’re completely right about that – boxing was never an art, just a brutal sport, one that we will be better off leaving to history.

Boxing is stupid and should be illegal.

The original CA governor Brown proposed banning boxing in the state after two prominent boxers were beaten to death in LA. His proposal went nowhere. But as Chris Hedges said, boxing’s taking itself out.