Biden’s order is a good start, but Rebekah Entralgo says it doesn’t cover immigration detention facilities, which are far more prevalent than regular private prisons.

President Joe Biden signing an executive order on the day of his inauguration, Jan. 20, 2021. (Adam Schultz, White House, Flickr )

By Rebekah Entralgo

Inequality.org

The stock of private prison giants like GEO Group and CoreCivic plummeted recently after President Joe Biden signed an executive order phasing out the use of federal private prisons.

The move was celebrated by criminal justice advocates as a small but necessary step towards reining in corporations profiteering from incarceration. To fully address these punishment profiteers, however, the Biden administration will need to take aim at every tendril of the private prison industry.

The most profitable of these tendrils is the mass incarceration of undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody. Biden’s order doesn’t cover these immigration detention facilities, which are far more prevalent than regular private prisons.

People detained in federal private prisons make up just 9 percent of the entire federal prison population. Meanwhile, over 70 percent of people detained in ICE detention centers are held in privately operated facilities. This is precisely why CoreCivic shrugged off Biden’s order, saying in a statement that the “announcement was no surprise.”

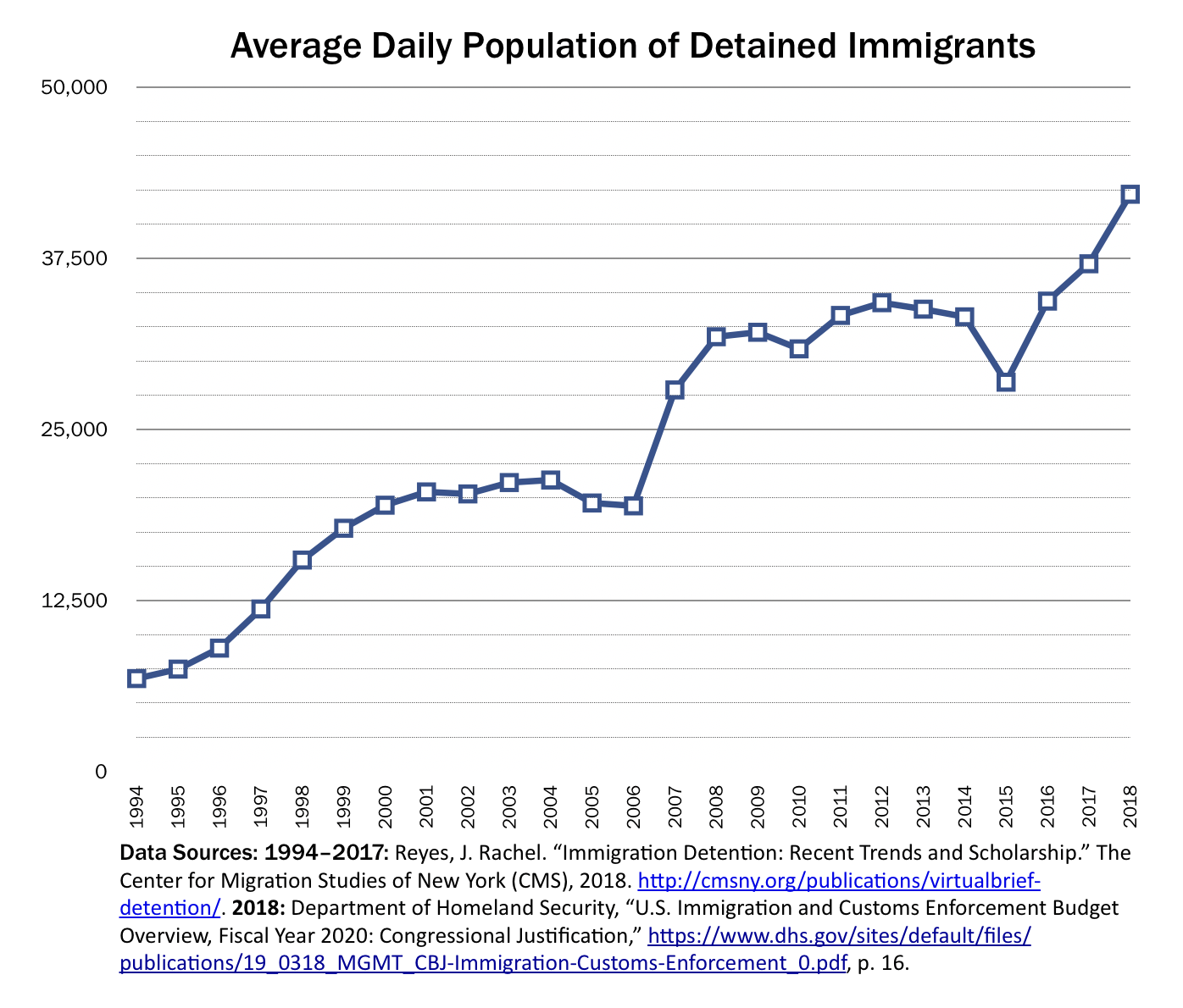

The Trump administration incarcerated immigrants and asylum seekers in greater numbers and for longer than ever before, creating a boom for the industry over the last four years.

Average daily population of detained immigrants held by the United States government for the fiscal years 1994–2018. (Carwil, CC0, Wikimedia Commons)

In April 2017, GEO Group won a $110 million contract to build the first ICE detention center of the Trump administration. By 2019, there were over 50,000 people detained in over 200 immigration detention centers across the country.

This explosion of privately operated immigration detention centers has had an abhorrent, tangible human impact on immigrant communities in the United States. Nearly every horror story that has emerged from ICE detention over the last decade or so has occurred at a facility operated by a private prison company.

The non-consensual hysterectomies of Black and Latinx immigrant women occurred at a detention center operated by LaSalle Corrections. The use of pepper spray and physical force against Black immigrants to coerce them into signing their own deportation papers occurred at a CoreCivic detention center. Karnes County Correctional Center, a family detention center with a history of abuse against immigrant children and their parents, is operated by GEO Group.

Inadequate Accountability

Abuses are inherent within any system, private or otherwise, that cages humans. But privately operated prisons are largely allowed to operate under a special cloak of protection, which allows for egregious violations to occur without any public accountability.

People apprehended by Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol agents in 2016. (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Wikimedia Commons)

CEOs and shareholders have been lining their pockets with cash generated from this abuse. CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger took home $5.3 million in compensation in 2019, an increase of 30 percent over the year before. GEO Group CEO George Zoley was paid roughly $5.6 million in 2019.

In part these paydays come from warehousing immigrants while cutting corners on safety, hygiene and health care. But another way these CEOs are likely to take home such large paychecks is by exploiting the labor of the very people they incarcerate.

In California, immigrants who were detained at prisons owned by GEO Group are suing the company for forced labor and wage theft. One of the class-action lawsuits alleges that detainees at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center were paid $1 a day for their labor, which includes cleaning the facility and working in the kitchen. A similar lawsuit was filed against CoreCivic.

These companies don’t just make their money from prisons either. After major banks like Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo cut ties with the industry, private prison companies diversified into re-entry services like “halfway houses” and ankle-monitors, a form of what advocates call e-carceration.

Biden’s recent order is a welcome first step toward reining in abuses like these, but the carve-out for immigration facilities still leaves enormous potential for harm. If we are to fully eliminate profiteering off human suffering, the cash incentives in all jails and prisons must be addressed.

Rebekah Entralgo is the Managing Editor of Inequality.org.

This article is from Inequality.org.

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Show Comments