Consortium News is virtually “inside” the courtroom at Old Bailey, viewing the proceedings by video-link and we filed this report on Day Nine of Julian Assange’s resumed extradition hearing.

US Again Insists Journalists are Not Precluded

From Prosecution Under the Espionage Act

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

Under resumed cross examination of defense witness Carey Shenkman, a civil rights and constitutional lawyer, the prosecution sought to clearly establish that Section 793(e) of the Espionage Act does not preclude a journalist being prosecuted for possession and dissemination of national defense information.

In numerous attempts by the prosecutor, Clair Dobbin, to elicit a simple affirmative response to this assertion, Shenkman instead unleashed a barrage of legal cases and scholarly opinion which amounted to “it’s not that simple.” “

“You ask, is there a law precluding prosecution of journalists, but there is a combination of statues and also the U.S. Constitution,” Shenkman said. “The Constitution is the law of the land.” Dobbin then led Shenkman into the deep weeds of three important Espionage Act cases involving the media. Shenkman added several of his own.

Dobbin first tried to get Shenkman to simply agree that dissenting opinion in The New York Times vs U.S. Pentagon Papers case left open the possibility that the Times could be prosecuted after the fact of publication. The Supreme Court decided that the government could not exercise prior restraint, that is, ordering a newspaper not to publish something in advance, as the Nixon Department of Justice had done.

Dissenting opinion in that case held that the Times could be prosecuted after the fact for violating the Espionage Act. Shenkman responded that since that issue was never argued in the prior restraint case that he couldn’t conclude that it meant journalists can be prosecuted post-publication.

Shenkman brought up the related Beacon Press case, and compared it to WikiLeaks. Daniel Ellsberg had leaked the Papers to Senator Mike Gravel, who put them into the Congressional Record by reading hundreds of papers at a committee meeting (Public Buildings and Grounds) and putting the rest into the record.

Gravel was protected by the Speech and Debate clause of the U.S. Constitution, which forbids any member of Congress from being questioned about anything they say in the midst of a legislative act. But Gravel then went to Beacon Press in Boston with the Papers to be published as a four-volume book.

For that he would not be protected and Nixon could have gone after him under the Espionage Act. Instead Nixon sent the FBI to Beacon Press offices and threatened to prosecute. This Shenkman said was an example of how the mere threat of prosecution and the legal cost incurred almost bankrupted Beacon Press and was an example of how an actual prosecution was not necessary to cast a chill over the free press.

Shenkman said this in response to a somewhat astonishing assertion by Dobbin that because the government had never actually prosecuted a publisher or journalist (before Assange) it meant the government was exercising restraint on its powers.

Shenkman drew a comparison between Beacon Press and WikiLeaks in response to Dobbin’s equally astonishing statement that the government had only threatened to prosecute large media in the past. He said that like WikiLeaks, Beacon Press wanted to create a library of classified documents.

“Do you understand the nature of the charges against Mr. Assange,” Dobbin asked. “Do you accept they bear no comparison to the examples you give?”

“I don’t agree,” Shenkman said. “In Beacon Press similar allegations were made about the entire set of the Pentagon Papers.”

“That is a frivolous and nonsensical statement in the face of the charges against Mr. Assange.”

“That’s your position, but the history and the evidence I submitted disagrees with that,” Shenkman said.

He also cited the case of the publication Amerasia, which the FBI raided and seized thousands of classified documents from in 1945. There was division in the State Department over policy towards China and some officials leaked the documents to bolster their side. The government tried to build a conspiracy case between the editors and the officials, Shenkman said, much like the case of conspiracy between the editor Assange and his source Chelsea Manning, but no indictment was brought against Amerasia.

Shenkman made plain that the reasons the government has attempted to prosecute editors and journalists was because they opposed the administration, revealed government misconduct or opposed its policies–reasons no different from any repressive regime. He went as far as to say the executive branch was making the actual law in espionage cases because it decided what was classified and what was defense information, and which cases to prosecute. Dobbin angrily dismissed this as “wrong.”

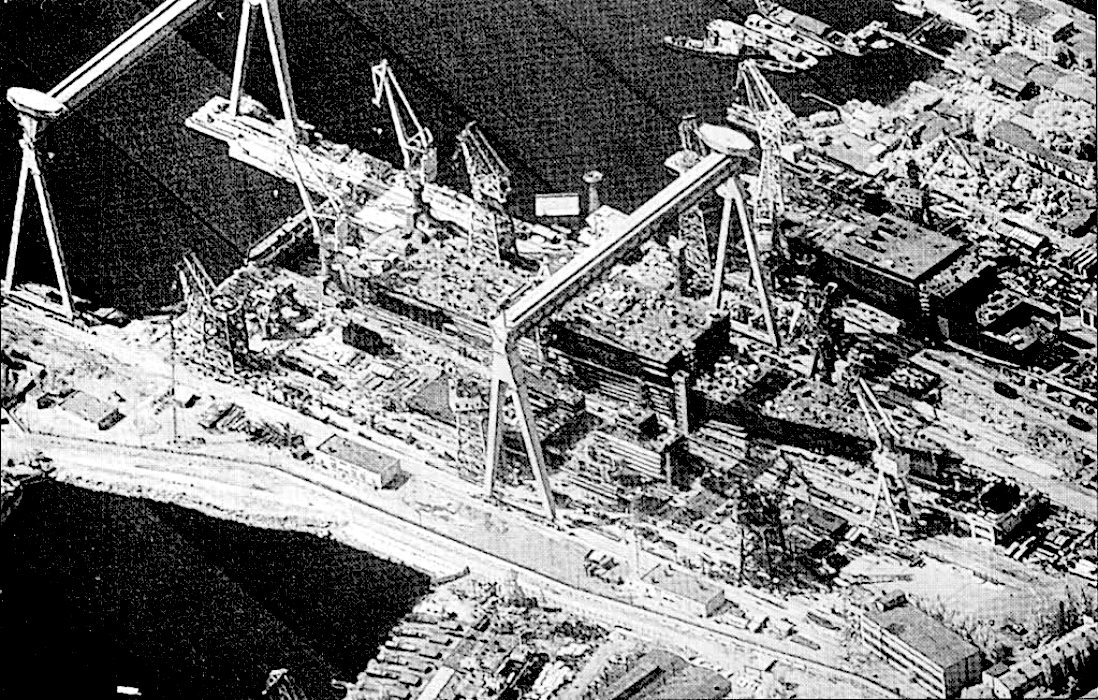

Dobbin then grilled Shenkman about the case of Samuel Morrison, an employee of Naval Intelligence, who in 1988 leaked classified photos of a Soviet ship to Janes Fighting Ships magazine. As a government insider who had signed a non-disclosure agreement, Morrison was charged under the Espionage Act. He argued that he was protected by the First Amendment because it was a leak to the press and not to a foreign government.

A photo of two KH-11 photos leaked to Jane’s Defence Weekly. It shows construction of a Kiev-class aircraft carrier, as published by Jane’s in 1984. (Naval Intelligence Support Center, public domain)

Morrison was convicted and lost on appeal. One of the appellate judges, Donald Stewart Russell, wrote that section 794 of the Act dealt with classic espionage but that 793 made liable any individual who had passed secrets to unauthorized persons and the person who received them.

As Dobbin pointed out, Russell dismissed the First Amendment consideration in the case. It was only on re-direct examination, that the defense established that two other judges in the case did consider the relevance of the First Amendment.

Dobbin also drew on the Morrison case’s rejection of the argument that the Espionage Act was overly broad, a contention Shenkman and many critics of the act make. Dobbin said the Morrison decision made clear that the government would limit its powers and not prosecute persons for ordinary possession of classified material that they may read in a newspaper, or a WikiLeaks release, and would do so only when it caused “damage” to national security.

The interaction between Dobbin and Shenkman was intense as they tried to out lawyer each other. At one point she angrily asked him: “Are you here to try to help Mr. Assange or the court?”

El-Masri’s Story Is Told in Court

7:52 am EDT: Judge Vanessa Baraitser ruled against Khaled El-Masri testifying from the virtual witness stand. She dismissed the Arabic interpreter from the court. The U.S. did not want mention of facts of El Masri case, which the Strasbourg court found to be true, because the U.S. had no input in that case, prosecutor James Lewis QC told the court.

El-Masri was kidnapped in Macedonia in June 2004 by CIA agents and sent to a black site in Afghanistan where he was sodomized, testified German journalist John Goetz on Wednesday. Goetz later found the CIA agents living in North Carolina and his cover story in Der Spiegel led to a German parliamentary investigation and the filing of an arrest warrant by Munich prosecutors for the CIA men, as El-Masri is a German citizen. But the warrant was never issued in the United States, where they lived.

Goetz testified that it wasn’t until the WikiLeaks release of diplomatic cables that he understood why. He said on the stand that cables showed the immense pressure the U.S. put on Germany not to issue U.S. arrest warrants, warning of serious repercussions in U.S.-German relations. Mark Summers, attorney for the defense, told Baraitser on Friday that El-Masri’s testimony about WikiLeaks‘ role in his story is why the defense wanted El-Masri to testify after.

Summers said Lewis wasn’t only objecting to the part of his testimony that laid out apparent criminal activity by the United States, but to its entirety, including as it touched upon WikiLeaks’ involvement in his case. At about this point, Assange cried out from his class cage: “I will not have the testimony of a torture victim suppressed.” Baraitser again warned him he would be removed if he spoke again in court.

John Rees, of WikiLeaks' @DEAcampaign, explains how US government "went to extraordinary lengths" to ensure Mr El-Masri's testimony wouldn't be heard in court resulting in Mr Assange shouting from the dock opposing the silencing of a torture victim.

via @SputnikInt pic.twitter.com/O3BfIbiyTM

— Mohamed Elmaazi (@MElmaazi) September 18, 2020

Baraitser compromised by allowing Summers to read into the record El-Masri’s testimony but not allowing him to appear on the stand. El-Masri had had technical difficulties logging into the court prior to this discussion. Summers said it was regrettable that Zoom couldn’t be used instead of the more complicated court video system.

Summers Tells His Story

Summers then told of how El-Masri endured five months of torture and was eventually released on condition that he not speak about what had happened to him. His release was in the dead of night in a place he did not recognized. Told to walk forward he feared being shot in the back. He then discovered he was in Albania and eventually made it back to Germany, where he “sought accountability” for what had happened to him, Summers said.

Instead he was treated with derision and threats until he found a German lawyer to pursue his case. Eventually Goetz pursued his story, discovering the CIA agents in the U.S. His Spiegel story led to the Munich arrest warrants, but as the WikiLeaks diplomatic cables showed, the U.S. deputy chief of mission, pressured German officials not to issue the arrest warrant in the U.S.

“As a result of the cables it is now known, but as not known at time of warrant, that Germany bowed to pressure not to seek the extradition of the 13 CIA agents,” Summers read. The effect of the U.S. threat was that a German and parliamentary probe into his case was impeded.

Summers says that the European Court of Human Rights in December 2012 decided El-Masri’s story was true, and its grand chamber said the WikiLeaks cable were relied upon by the court. FOIA lawsuits in U.S. revealed that the CIA inspector general had investigated the story and determined that El-Masri’s torture and detention was unjustified.

El-Masri then commenced a lawsuit in Eastern District of Virginia, Summers pointing it is the same court Assange is involved with, against the CIA agents and those who controlled them. But the U.S. attorney declined to pursue the case.

The ACLU initiated proceedings in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights which led to a complaint to the International Criminal Court, which in March decided to investigate. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reacted by saying that extreme measures would be taken against the ICC and its prosecutors. “Mr. El-Masri said that without the brave exposure of state secrets what happened to him would never have been understood,” Summers said.

Robinson Tells Court of Congressman’s

Offer to Julian Assange in 2017

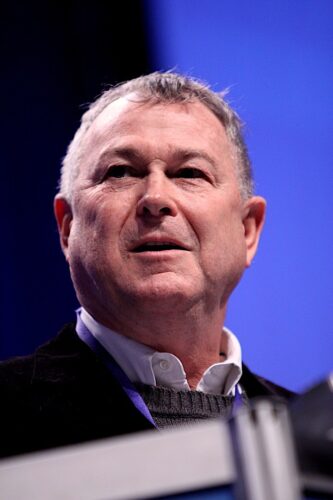

7:24 am EDT: Jennifer Robinson, a member of Assange’s legal team, had a statement read out in court on her behalf in which she recounted a visit by then U.S. Congressman Dana Rohrabacher to Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in London on Aug. 15, 2017 where Robison was present.

Robinson said in her statement that Rohrabacher claimed to be representing President Donald Trump on a mission in which the president would look favorably on preventing an indictment of Assange in return for the WikiLeaks publisher naming his source for the Democratic National Committee emails.

The leaks before the 2016 U.S. presidential election had led to a firestorm of allegations that Russia had provided those documents and that Trump was somehow in league with Russia and WikiLeaks to hurt his Democratic challenger, Hilary Clinton.

Rohrabacher told Assange, according to Robinson’s statement, that Assange could help Trump politically as well as to end the dangerous escalation of Cold War-like tensions between Russia and the United States if he could provide evidence of who the actual leaker of the Democratic emails was. “Rohrabacher proposed a ‘win-win’ situation, Mr. Assange can get ‘get on with his life’ – a pardon in exchange for information about the source,” Robinson’s statement said. “Information from Mr. Assange about the source of the DNC leaks would be of value to Mr. Trump.”

Assange refused, Robinson’s statement said.

James Lewis QC for the prosecution rose after the statement was read to say the U.S. government did not contest that Robinson was telling the truth but that it did not accept that Rohrabacher was.

Informants Are Still the Issue for the Prosecution

6:35 am EDT: First defense witness was Nicky Hager, a New Zealand investigative journalist, who testified, as other defense witnesses have, that Assange took extraordinary precautions in redacting names of informants from WikiLeaks documents before publication. Hager worked with WikiLeaks on documents pertaining to New Zealand and Australia.

Hager also spoke of the value of the leaks in his writing of several books, including one Hit and Run, about the conduct of New Zealand troops in Afghanistan.

On cross examination, prosecutor James Lewis QC attempted to show that Assange recklessly published the entire un-redacted contents of the diplomatic cables. Lewis again brought up the incident at the Moro restaurant in London where David Leigh and Luke Harding allege in their book that Assange said he didn’t care if informants were harmed.

John Goetz, a German journalist present at the dinner, took the stand earlier this week was was stopped by the judge from saying that Assange never made such a statement. Hager said he wouldn’t comment on what he saw as an unreliable statement about the dinner in Leigh and Harding’s book.

Lewis then got Hager to testify that he never needed to name informants in his own work, implying that Assange didn’t either. Lewis tried to corner him into saying that he spent only a few days redacting names from the WikiLeaks documents that he worked on in regard to New Zealand, while Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist who Lewis mischaracterized as male, has testified in her written statement that she and another journalist took nine months to redact 4,000 pages.

Hager said that in the New Zealand context named individuals would only suffer political embarrassment, and not harm as in Afghanistan.

Lewis again made the point as he has before that Assange is not charged with releasing the Collateral Murder video, which Hager mentioned in his witness statement. But on re-direct, defense attorney Edward Fitzgerald was able to establish that the video is still relevant to the case because Assange has been charged with receiving and publishing the Iraq rules of engagement, without which one cannot determine that the video violated them.

That he was charged with this also again establishes the falsity of the prosecution effort to say Assange is only being charged for releasing documents with informants names.

The prosecution brought up a statement, as it has before, that Assange made at the Front Line Club in London in 2011, in which Assange said WikiLeaks had no obligation to protect other people’s sources from “unjust retribution.” Fitzgerald on re-direct examination point out that that could mean sources who were agent provocateurs and that journalists had in the past revealed, such as in Northern Ireland.

Friday morning’s testimony again saw the prosecution zeroing in on the naming of informants. Hager joined other witnesses in explaining that WikiLeaks only published the unredacted cables after Leigh and Harding published the password to them in their book.

5 am EDT: Court is in session.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’

25th Anniversary Fall Fund Drive

Donate securely with

Click on ‘Return to PayPal’ here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

The USA has fallen a long, long way during my adulthood.

Who could have foretold that the USDOJ would promote and support Supreme Crime?

We have fallen such a long way that there is now no stopping point. Monsters in power will complete the destruction of the West, and probably all of Planet Earth

destruction of Planet Earthof

==========

May be the best possible outcome.

Destroyed Planets according to some become Stars, great for Green energy, end pollution.

The best weapon of a dictatorship is secrecy, but the best weapons of democracy should be the weapons of openness.

Niels Bohr

M Paterson I completely agree with your assessment. It is now becoming abundantly clear that Baraitser has turned this into a kangaroo court and is manufacturing a sublective reality based on how Pompeo and the CIA want an end result to be administered. Nevertheless historically the US MIC came to the realization that Ellsberg was instrumental from stopping the US from charging headlong into the abyss of Viet Nam and that if it continued much longer the US would have fractured irreparably. The savage diabolical Apache attack on helpless citizens gathering in their hometown in Iraq has been seen the world over and the world knows that it is the release of that video which is driving the US into a frenzied pursuit of Julian. Thank you Consortium News! It is your courageous reporting which could possibly save Julian from extradition

Joe, your account of Julian’s outburst from the glass cage

“I will not have the testimony of a torture victim suppressed”

and its evident impact on Baraitser, in her agreeing that El Masri’s written statement could be read out in court, is remarkably moving and heartening. To me this must have been the high point of the day in court.

El Masri ‘s read-out statement is shocking in what it says about CIA power and ruthlessness and US oppression of Germany. It must have an impact even on Baraitser. Or maybe I am being too hopeful?

Tony Kevin

This is like a heresy trial, the film ‘The Devils,” based on Huxley’s book, THE DEVILS OF LOUDON.

Everyone seems aware we’ve achieved Orwell’s 1984, but no one mention’s Huxley’s BRAVE NEW WORLD any longer–which we are steaming into, now, at a blinding rate of speed. And this treatment of Assange is a perfect example of how this social-psychological formation will function not only now, but in the future.

Is it possible that the momentum of the state’s reckless pursuit of Assange has carried it’s diabolical behavior into the sunlight.

The most obvious observation that can be made of this spectacle is this application of the perverse bias compromising of the practice of law based on the prosecutions purely political agenda.

Thanks to the reporting we are getting anyone interested can deduce for themselves what they witness here, it is very plain to see.

Look long and hard friends, this is Justice as bowed to the will of the current U.S. Department of Justice, one Billy P. Barr and his nationalistic supporters.

Your reporting of the court procedures on the Assange case is invaluable for Assange and legitimacy of western systems of justice. Thank you so much, Craig Murray and all of you at Consortium News.

The 18th Century Economist, Frederic Bastiat wrote “When plunder becomes a way of life, Men create for themselves a legal system that authorises it & a moral code that glorifies it! This is what we are seeing with the immoral persecution of Journalist, Julian Assange & this sham English Kangaroo Court? Assange laid bare the Criminal conduct of the UK & American Govts in their Wars of Plunder & Resource theft, which is the real reason why all these Wars, in the Middle East, are conducted? It’s modern day Piracy & Corporate Warfare to steal another Nations Oil or any other Resources or minerals that the greedy Hegemonies want! Notice that Bastiat wrote that these Men or Nations create a legal system that legalises the crimes & a warped moral code that justifies & glories the plunder & criminality! Assange is a victim of this depraved moral code & a legal system created by these crooks & thieves to abuse International Laws & use archaic Laws such as the Espionage Act here, to justify & legalise the Criminal thievery committed by the USA & other Western Govts that we’re complicit in the plunder of Iraq, Libya & many other Nations! Plunder becomes a way of life or normalised to these Nations & they create a LEGAL SYSTEM to enforce the thievery & a moral code that GLORIFIES it!

I cannot agree more.

The National Security Act of 1947 was passed in large part to protect the nuclear technology or so the story goes.

In fact history tells us that most of the critical secrets of all things nuclear were known far and wide, although it be known only to a select few nations and by none of the “have not” nations.

It turns out the National Security Act has been much more successful in keeping Americans in the dark than preventing prying minds from braking American security efforts with respect to all things nuclear.

KiwiAntz you have hit on a vital factor in what has ruined America. Mr. Bastiat’s quote can be applied to Julius and Ethal Rosenburg, Robert Oppenheimer. Some additional searching will expose Edward Teller had many, more than worrisome, connections to spies during the same period has aspersions on Oppenhiemer, see pages 429-430 Richard Rhodes, book Dark Sun, the time period around 1950.

The new National Security Act was in place and protecting those the government wanted protected as opposed to protecting Americas secrets. America’s perverse relationship with the State of Israel is the perfect case in point for this matter.

NUMEC come along 1953-54 and all outward appearances indicate the Zalmon Shapiro was giving the same pass as Edward Teller.

Now King Flu Trump wants to nationalize the U..S. educational system and create a “Trump [hitler youth] re-education program.

Don’t tell me who’s going to win. Just give me the point spread.

I’m speechless…..

Prayer #3: Oh justice ain’t it so metaphorically sometimes you are a “poke in the eye” to the offender? I say so, and if I poke out one eye, then I’m gonna poke out the other as well. Oh justice, I now you are ruthless, especially when it is time for justified retribution….I pray the time is nigh.

Is it likely that the “Judge” Baraitser is starting to experience behind the scenes pressure being mounted by some in the Judiciary who can’t stomach the trashing of the reputation of the British Justice system?

My reading of the internet articles referring to the Julian Assange extradition hearing is that many people through-out the Western world are losing confidence in the “rule of law”, which has been espoused by Western politicians, lawyers and bureaucrats as being the pinnacle of justice.

Don’t the nations’ establishments realize that by setting aside their own laws, as and when they please, that this is instituting tyranny?

The reaction to this by “the peasants” is more protests, riots and eventually revolution. History is replete with examples. For example The Peasants Revolt, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution and in Australia, the Eureka Stockade.

Because of the behavior of one of their own, the British Judiciary will lose reputation as the people will start to feel contempt for the system of Justice which is daily demonstrating its unfairness. This will apply not only in the UK and the USA but in other jurisdictions as well. The courts will be seen as an instrument of oppression. Is it too late to do something? Over to you.

M. Paterson. I was mentally agreeing with you until reality struck home. Consortium News is a small but valued news site, that most of the Judiciary has probably never heard of as they more than likely follow far more reliable outfits like The Guardian, The Telegraph and the BBC.(sarcasm) Never the less it’s nice to feel a note of optimism

The Assange Witch Trial lead to Revolution by the Masses?

We can only hope so.

“When in the course of human events, it becomes NECESSARY….”

Thomas Jefferson