The key question after the Aug. 4 explosion in Beirut revolves around the role of the Lebanese Army command, which is the sole authority with direct control over the security and safety of the port, and its surroundings.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Those who are superstitious may think that Lebanon has been recently cursed: successive disasters, catastrophes and crises have afflicted the small country uninterruptedly for several consecutive years.

Those who are superstitious may think that Lebanon has been recently cursed: successive disasters, catastrophes and crises have afflicted the small country uninterruptedly for several consecutive years.

Lebanon has been suffering from one of the worst economic crisises in its history and young people in Lebanon have launched protest movements twice: once in 2015, with the limited goal of solving the trash crisis, and then in October 2019 with the more ambitious goal of changing the political system altogether.

But the protest movement has stalled, largely due to its infiltration by right-wing movements of various corrupt politicians (like Saad Hariri, Walid Jumblat, and Samir Ja`ja`), and also by various NGOs, which have been effective in spoiling and undermining progressive movements in the Arab protest movement.

At the time of the blast, Lebanon was suffering from the collapse of its currency and the the loss of people’s savings (and even checking accounts) in Lebanese banks. And then the coronavirus hit, followed by the massive explosion that killed at least 200 and 6000 injured.

The shape of the city has been altered. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed and poor workers at the port, mostly Syrians, were killed.

It was a blast like no other in the history of the Lebanese civil war; my sister—who lived through the various stages of the war—described it best: every Lebanese felt it and it felt as if it were right next door. The suffering is indescribable and the damage is estimated by the government at $15 billion (international donors could only collect “pledges” of a few hundred million dollars).

The explosion was the last straw for most people in Lebanon. The protest movement has not been fully revived, but there are expressions of public anger in all mainstream and social media.

The story of the explosive chemicals has been told in U.S. media but the Lebanese people still pose many questions that remain unanswered. The key question revolves around the role of the Lebanese Army command, which is the sole authority with direct control over the security and safety of the port, and its surroundings.

The Lebanese Navy has a base at the port, and Lebanese Army intelligence directly oversees the security of the port. Yet, no Western media, nor much Lebanese media for that matter, have pointed fingers at the Lebanese Army and its commander.

The reason is the U.S. has never had as much direct control over the Lebanese Army as it does now. The commander, Gen. Joseph Aoun, enjoys great support from the U.S. government, which (comically) promotes the man as the most able to defend Lebanon against all dangers. Meanwhile, the Army has never defended Lebanon from Israel, and it has failed against militant Islamists.

Furthermore, with all the attention put on Hizbullah and its militia in Lebanon, rarely is the U.S. military presence in Lebanon discussed. In the name of “training purposes,” the U.S. military is all over the country.

The U.S. is said to be training the Lebanese Army on counter-terrorism, yet when ISIS and Nusrah Front kidnapped and killed soldiers of the Lebanese Army in `Irsal in 2014, it was Hizbullah volunteers who launched a war against them, while the Army stood by. This is similar to what happened in Iraq. When the U.S.-trained Iraqi army collapsed in the face of the ISIS offensive, it was the hashd militias (known as Popular Mobilization Forces, unleashed by a religious edict from Grand Ayatullah Sistani) that undertook the offensive against the ISIS attack.

A Confessional Failure

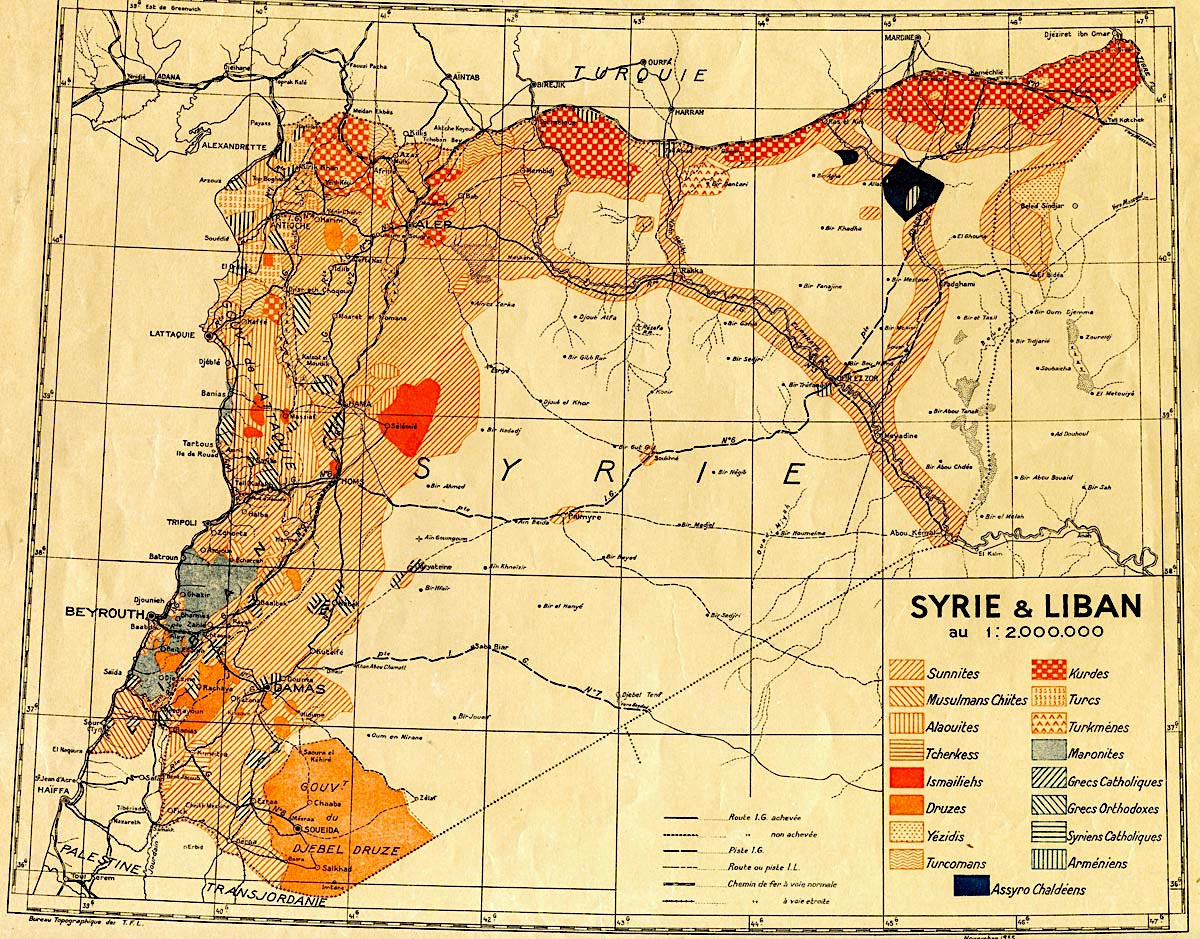

A map of religious and ethnic communities of Syria and Lebanon, 1935. (Map prepared by the Bureau of Topographic French troops in the Lebanon. – (La cartothèque de l’Ifpo (Institut français du Proche-Orient)

The Lebanese political system, which was set up by the French colonial power after World War I, when Britain and France divided the spoils of war in the Arab East between them, was designed by Paris to maintain Maronite political supremacy.

A complicated system of sectarian distribution of posts and power according to an arithmetic formula was intended to keep the system squarely in the hands of the Maronite elite, while giving token representation to Muslims behind a democratic façade.

But demographic changes, to the advantage of Muslims, clashed early on with the French arithmetic formula and that contributed to internal turmoil and civil strife, first in 1958 and then in a full-blown, protracted war in 1975. (In Lebanon, internal sectarian conflicts always have external dimensions, because since the 19th century, European powers forced on the Ottoman Empire a system of foreign sponsorships of Christian and Druze sects in the Arab East.)

Now what is the relationship of this archaic system to the blast in Beirut?

The answer is simply this: it is at the root of the corruption that explains the incompetence and mismanagement of the Lebanese state. There are external elements of Lebanese political corruption (which I will treat in a future article), but there are also indigenous factors.

Sectarianism basically produced leaders and constituents who are set apart from other sects in the same country. Politically speaking, sects live together, but separate from one another, and that impedes national unity.

Just like Iraq today (where the U.S. copied the system of ethnic and sectarian division of spoils from Lebanon—of all places), Lebanon has been unable, since independence from France in 1943, to forge a national identity or a concept of citizenry. For instance, there has been no agreement since the civil war on writing a unified history textbook.

The state only recognizes the individual insofar as he or she is a member of a sect: you are forced to be born, married, and buried according to the rites of the sect you are born into, even if you are an avowed atheist.

Political bosses of Lebanon (known as zu`ama’) are sectarian leaders and are rarely national leaders. Thus, their primary responsibility is to their sectarian audience, which increases their motivation to engage in sectarian agitation and mobilization because a national citizenry would leave them jobless.

The fact that those leaders receive money from various countries of the world make them independent of the state (and many of those bosses are outright billionaires). But once they are in the state, they help themselves to the treasury according to a system of division of spoils.

The system is not based on merit, nay it clashes with merit, because the goal is to appoint individuals, not for their talents and skills, but for their fealty (that was exactly how Yasser Arafat operated in Lebanon and explains the demise of the PLO and its inability to create an effective fighting force against Israel in the country.)

Even if a political boss appoints a qualified engineer or professional manager, the person is dependent for his or her job on keeping the boss happy, i.e. helping in looting the treasury. The appointees at the Port were of that caliber, and the same applies to the Lebanese armed forces and intelligence services.

It Got Even Worse

From left to right, Gen. Joseph K. Aoun, commander, Lebanese Armed Forces; and U.S Army Maj. Gen. John P. Sullivan, assistant deputy chief of staff, G-4; walk through the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia, June 26, 2018. (Wikimedia Commons)

This system, however, took a sharp turn for the worse in 1992, when billionaire Rafiq Hariri was installed by the Syrian-Saudi alliance, and with the approval of the U.S. This prime minister used the treasury and his own money (sometimes) to place many elements of the bureaucracy on his personal payroll or on the payroll of the state budget he controlled.

The multiplicity of sects means there is redundancy in the bureaucracy: the Sunnis control one intelligence branch, the Christian another, and the Shiites a third, without any need for this variety. Similarly, the Port was under various directors: one for customs, and another for the port itself (the former is loyal to the Hariri family while the latter is loyal to the country’s president.) But overall security of the entire port was in the hands of Army intelligence (which has become—under the current director—more independent from the political bosses and closer to the U.S. government).

When it comes time for accountability, each leader or each sect points fingers at the other. If one person is found guilty, the religious head of the sect raises the alarm and prevents court proceedings from taking place as the judiciary is as corrupt as the political system because the political bosses appoint the judges, who in turn are loyal to a sectarian patron.

Only recently, there was public anger against Riad Salamè, the Central Bank governor since 1993, who was the real architect of the financial Ponzi scheme that triggered the financial collapse of Lebanon. Not only did the U.S. government protect him by issuing direct threats against the Lebanese government in case he was fired, but the Maronite patriarch also intervened to prevent any government prosecution of Salamè, or even his dismissal. (The banker appointed by Rafiq Hariri is known to facilitate financial transactions for the church).

Similarly, as the public in Lebanon demands accountability for those responsible for the blast, the corrupt system is unlikely to settle on one culprit.

Domestic Responsibility

Michel Aoun, President of the Lebanese Republic, addresses European Parliament, Sept. 11, 2018. (© European Union 2018 – European Parliament)

There are various levels of corruption, incompetence, mismanagement and recklessness in the performance of the Lebanese government which resulted in the blast—even if there was a so-far unproven external hand—such as Israel, which has a history of sending booby-trapped cars, trucks, and donkeys and detonating them in crowded Lebanese neighborhoods. Israel did this while claiming responsibility in the name of a fictitious organization it invented to make its crimes seem indigenous (the name of the organization was “The Front for the Liberation of Lebanon from Strangers”, see).

Who stored the explosive chemical ammonium nitrate in the port, and who put the explosive material next to a warehouse of firecrackers? Who left it unattended for six long years? When did government officials know about the dangerous chemicals (or even U.S. government officials, as we now know there was a Pentagon contractor who had access to the port and inspected it and found the dangerous material)?

There is evidence that only weeks before the explosion President Michel Awn and Prime Minister Hassan Diab both received a report about the material. And it was only one intelligence agency (the “Security of the State Agency”) which had warned about the danger, but even this organization did not raise a public alarm about it.

Most importantly, when did the Lebanese Army command know about this stored material—it is certain that they have known all along—and why did they not act? There is also another question to be posed to Lebanese Army command: the fire took place for many minutes before the big blast: why did the Army fail to evacuate the area and warn the citizens before the explosion?

A Long Crisis

People in Lebanon did not need this latest scandal to rise up against the government of Lebanon. But the task of overthrowing the Lebanese government much more difficult than overthrowing governments in other Arab countries—as difficult as that task is, given Western sponsorship of most Arab governments. (In Syria, the regime sought Russian and Iranian intervention to stay in power.)

In Lebanon, the regime is democratic in name (which gives it a veneer of political legitimacy) and too resilient because the security of the regime is tied to the security of the sect. When political bosses are really threatened, they quickly resort to sectarian agitation and mobilization to divert attention and anger away from the ruling class and toward members and leaders of other sects. This has been the case since at least the 1840s.

Lebanon will never be the same after this incident. While actual reform of the regime is unlikely, the ability of the government and the ruling classes to go back to the “normal” ways of Lebanese politics has at the same time been severely hampered. This is a long crisis with no end in sight.

There is a great opportunity for radical change in Lebanon, but there are no potent, political movements at the moment. The protests so far have been either too timid or too cartoonish to cause real harm to the ruling classes.

Too much of the energy of the protestors (some—not all—of whom were infiltrated by right wing movements and organizations who work closely with the Saudi and UAE regimes) was focused on the person of Jubran Basil (son-in-law of the president and leader of the largest parliamentary bloc).

The protest movement has failed to shake the foundations of the system and force the ouster or resignation of the political bosses. The ruling class will come back in full force with the support of the Western governments that sponsor most of them.

There is little ground for optimism in Lebanon.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium

News on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button: